Texas Calling

As told to Alex Rawls

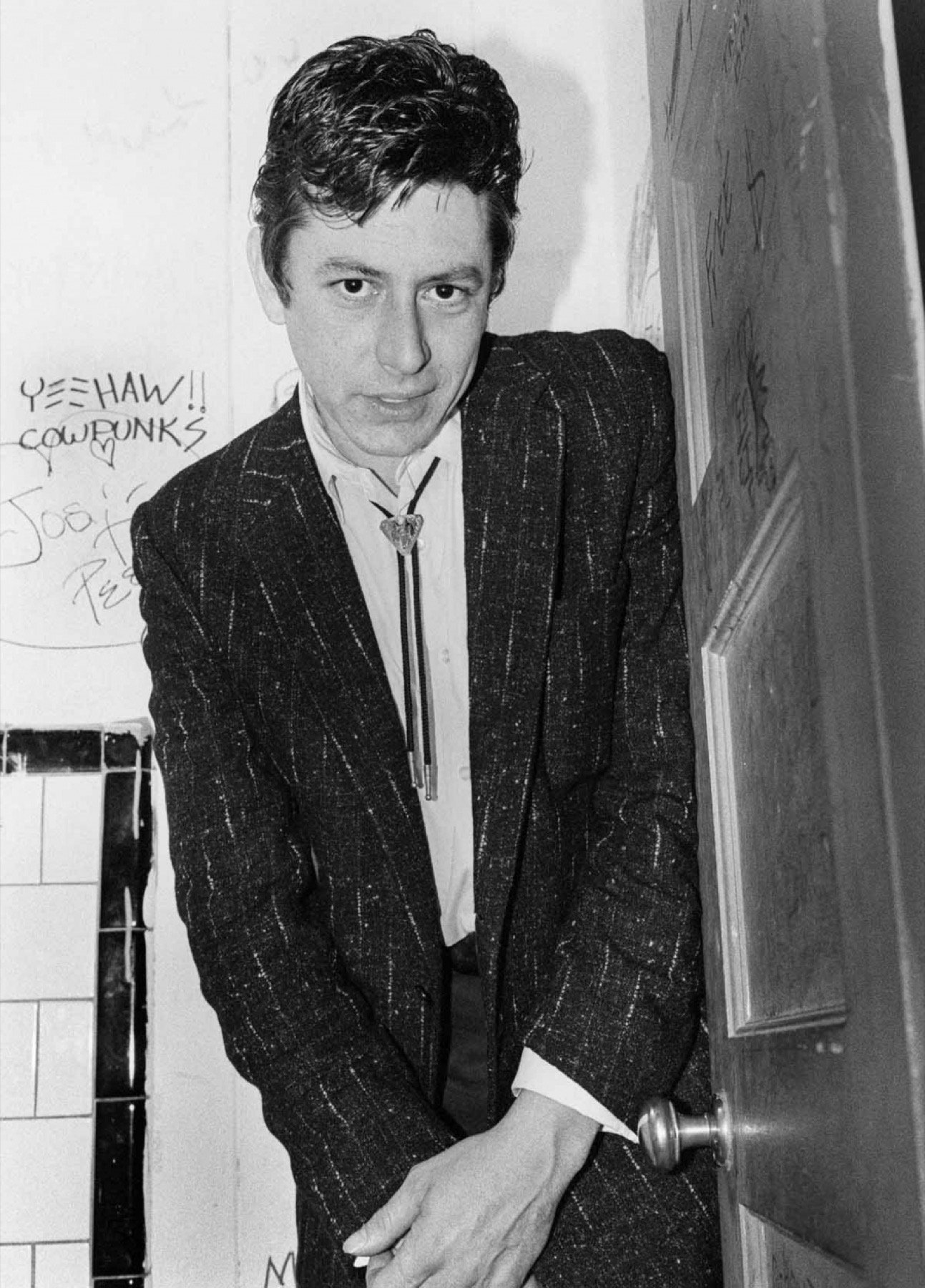

Joe Ely’s rowdy self-titled debut album from 1977 brought a rock & roll spirit to its mix of country, blues, and folk music. The record was largely ignored in America but found an audience overseas, and on one tour Ely struck up a relationship with the Clash and particularly Joe Strummer. A few months later, they were touring Texas together. “I don’t remember all the good nights,” Ely says, laughing, “but I remember the bad nights really well.”

When we first met the Clash, it was probably ’78 and we had a record that was doing pretty well in Europe and especially in England, where it was getting a lot of radio play. I didn’t know anything about the Clash or the Sex Pistols or Elvis Costello or Nick Lowe or Dave Edmunds or all the people who were making the music that I could relate to. I was stepping into a whole different world and had no idea about the Clash until we started hanging out together. They had heard our stuff in London, but we had no idea who they were until we met at our first shows over there. They were a scruffy lot. Somebody had told us that a band had come to see us at sound check, but when we first saw them, we didn’t think they were a band. We thought they were probably trying to steal our gear.

We all talked, and they took us out on the town and showed us around England—the hot spots like The Hope & Anchor over in Camden that was sort of a late-night pub. We were doing press and a few shows, springboarding in and out of London. We got together whenever we could, and we formed a bond. Me and Joe Strummer found we liked the same poets, like García Lorca, and we liked the same rockabilly guys—Eddie Cochran and the Everly Brothers—and because we were from Lubbock, they asked a lot about Buddy Holly. Their first hit song in England was “I Fought the Law,” which was written by Sonny Curtis, who was from Lubbock and wrote songs for Buddy Holly.

Before we went back to Texas, Joe said, “You know, we’ve never been to the United States. We’d love to come and do some shows together.” I said, “Give me a call and we’ll see what we can do.” Sure enough, a few months later we set up a tour around Texas, and we played the Monterey Pop Festival together. We played the Hollywood Palladium, and it was like a battle with the audience. Because of the Sex Pistols, when the band came on they threw cans at them. People were trying to cut the microphone cords with knives. I remember Joe stopping the show and saying, “Where we come from, all the kids are poor. They’re broke. There’s 40 percent unemployment. There’s people on the dole waiting in line to get a menial job, and here I look out in the parking lot and it’s full of Mercedes-Benzes and y’all are throwing stuff at us.” American audiences didn’t understand what the Clash were talking about. They were being cute little rebels, but the Clash were really serious about what was happening with racial tensions in England, the unemployment, the whole thing.

We played some of the places he wanted to play in Texas that were the names of Marty Robbins songs. They thought they were on the moon when they got to Lubbock and the streets were wide and all the buildings were one story tall and tumbleweeds were blowing down the street. They couldn’t believe where they were. In Lubbock, a city of a hundred thousand people, there were four or five bands, max. It wasn’t a time like now where every city has three thousand bands. We’d go out to Buddy Holly’s grave with a case of beer and sit out all night singing Buddy Holly songs.

We played a place called The Rox. The building is barely there, but that show went well because I had a huge following in Lubbock. It was packed, and everybody was really curious about the Clash. I remember at the end of the night we played some songs together we had worked out for the Monterey Pop Festival, which was the first show on that whole string of dates. We did “I’m So Bored with the U.S.A.” It was such a full onslaught of power chords that the meaning of the song completely flipped. All of a sudden, it’s “I’m rocking out in the U.S.A.” I think we did “I Fought the Law,” and one of my songs, “Fingernails.” We also did “Brand New Cadillac.”

I had to call all around because nobody would touch that show. They said, “Okay, let me get this straight. A punk band from London and a honky-tonk band from Texas are going to do a tour together?” They thought it was suicide. I believe the guy who did it was a rodeo promoter from Odessa, Texas. He knew the rodeo circuit, and that’s how come we ended up in the places that we did. We played the University of Houston on a proper stage, and the place in Dallas that I think was called The Palladium that had a proper stage. But some of the places were pretty makeshift.

Joe looked at touring as a way to see places that he’d heard about in Woody Guthrie songs and Marty Robbins ballads. I guess I’ve been the same way in my life. It’s never like you think it’s going to be; in fact, I think the Clash were a little bit disappointed in Texas. They thought it still had swinging doors and hitching posts. But it was great fun once they got over the shock of the difference between what was in their imagination and what the reality was. Laredo was pretty dusty—on the Texas side, just a little small town. On the Mexican side it still had dirt streets in a lot of places. It was really poor, so poor people carved out the inside of a cactus and put a piece of tin over the top and lived inside of it. Strummer was really interested in that kind of poverty—how such a poor third world country could live door to door with the richest country on Earth.

We played a high school gym in Laredo, and all I remember was the terrified looks on the kids’ faces. The Clash in a gymnasium seemed kind of abstract, and our band didn’t play schools. We played old roadhouses. It was quite a few people and they were all very young, like high school age. They got me more than them because we had a pedal steel and an accordion in our band. They were very polite. All the audiences were polite. Everybody had some weird sense of how they should behave.

I can’t remember the place we played in El Paso. After the show we went over to Mexico. Joe was fascinated with mariachi bands—the whole concept of the mariachi band was something he’d never witnessed. The first part of the night, he wouldn’t let the mariachi bands loose. He kept tipping them. He was fascinated that they were wandering from bar to bar. One band would walk out the door and another would come in. Each band was a complete unit that didn’t need a stage. I remember me and Joe getting up and singing a few songs, trying to figure out what they knew. “I Fought the Law” was originally recorded by Bobby Fuller, who lived in El Paso. Joe was real fascinated with Bobby Fuller—not only his music but the strange circumstances around his death. He was found with gasoline in his stomach. A lot of the Mexican bands knew the Bobby Fuller version of “I Fought the Law.”

I played with them at Bond’s in New York in 1981, and it was a wild crowd, but it was civilized. They were going to play one or two shows, then they added a bunch of shows, then they added even more shows. The hardcore fans of the Clash were organizing whole protest groups, and it had this very real sense of danger about it. I don’t remember the actual playing. We were hanging out in New York at the time, and Strummer had in his hotel room this typewriter he’d bought in Times Square that was from Finland or Russia or something. He was writing these songs out, but he had to remap the whole keyboard in his head to find the letters that were closest to English letters. After the show we did with them, I remember going to a party with them over at the hotel. At 5 or 6 in the morning, me and Joe and our girlfriends decided to go ride the Staten Island ferry right before dawn.

In ’85 or ’86, I ran into Joe in London and hung out for a couple of days. The next time I saw him was in California probably the next year—’86 or ’87—and we hooked up in L.A. and by that time we both had kids, and our kids went to Disneyland together. We were out there doing a video and had a few days off, so we hung out and drove around. Joe had an old Sixties Thunderbird and he was really proud of that. He always liked Sixties cars.

When they were here in ’81, they came out to the house. In South Texas when it rains, there’s a phenomenon of these little insects that light up. Some people call them fireflies, but in South Texas we call them lightning bugs, and they’re all down in the field below my house—a two or three-acre field, completely full of them. And I’ll never forget their complete, total disbelief that they were insects that lit up. They thought that I had run a bunch of little bitty lights all through that field, and that I was somehow controlling them. Until we actually got some jars out and said, ‘Alright, watch this,’ and I’d go up and catch one in the jar and put my hand over it. I’ve never seen people turn into instant kids and go out collecting big jars full of lightning bugs. We probably did that for several hours. The next day, we went out and drove these go-karts, and Mick Jones was terrified. Growing up in London, it’s ridiculous to have a car, and so he’d never driven a car. He was going about three miles an hour, and we asked him what the matter was. He said, “Some of us are meant to be driven.”

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.