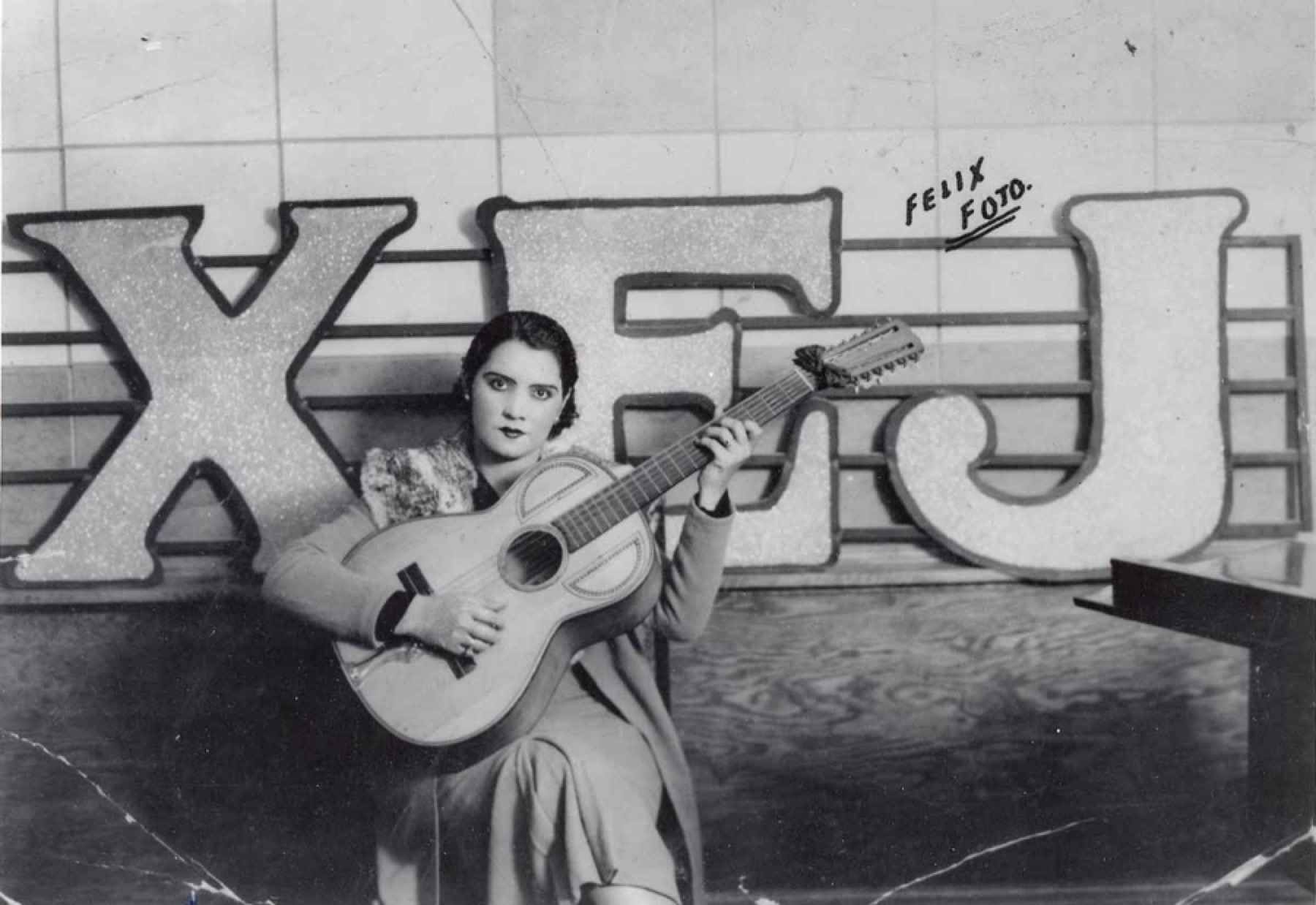

Photo of Lydia Mendoza at XEJ. Courtesy of the Arhoolie Foundation's Frontera Collection

An American Sound

By Ada Limón

Tracing complicated family stories is like trying to cross the desert holding water in your hands. What’s left is only an unidentifiable drop of what was once there. On one side of my family, our story spans a desert and a river and a border. Francisco Carlos Limón, my father’s father, came to the United States with his mother and sisters to escape the Mexican Revolution. I remember the story well. Pancho Villa confiscated their land in San Juan de Los Lagos. They crossed the border in Texas. They struggled and then eventually succeeded. It’s a tale not all that different from any immigration story.

But borders are complicated, and anyone with kinfolk who came from Mexico will understand what I mean when I say facts tend to get a little fuzzy around the Rio Grande and the most frequently crossed international border in the world. Like songs the stories shift and change as they are repeated in a gorgeously twisted game of bilingual telephone through the generations. As an adult I learned the slightly messier truth: Francisco Limón crossed around 1928—when the revolution was long over and Pancho Villa had already been shot forty times in his Dodge Roadster—one of five hungry kids living in a chicken coop in Canoga Park, running booze for a bootlegger around the California-Mexico borderlands. They weren’t escaping a war; they were escaping an abusive father. It was San Diego, not Laredo. He crossed by pickup truck, not by river.

The descendants of Mexican-American immigrants often hear a vague collective narrative of the epic border-crossing journey of our ancestors because, even if the facts are somewhat unclear, it’s essential that we bear witness to that time of transition. We are required to remember that our bloodline lived in the hazy hinterland of two countries—because that’s where the spark started, where the desire to be or build something new took hold. That’s where the obsessive, sometimes magical, and far too often false, American Dream began.

In another life, my grandfather could have been a great Mexican-American star. Over the long, blazing Southern California summers we shared by the ocean, Grandpa wearing his maroon velour robe and a small straw sombrero, he told stories—of playing extras in Hollywood films or performing as a Spanish dancer in a resort called Padua Hills—and he sang. His songs are as much a part of my memory of him as the sound of his spoon repeatedly clinking against the glass as he attempted to make his Coca-Cola flat (he didn’t like the carbonation). “La Valentina” while driving us to Ocean Beach in his dark red Buick packed with boogie boards and picnic supplies. “La Llorona” on the walk to the pool in the tiny retirement community where my grandparents lived, past the identical doublewides with their front lawns carefully landscaped in gravel the color of Pepto Bismol and ornamental cacti. I didn’t know then that Grandpa’s songs were traditional Mexican ballads, corridos, that connected an entire community of Mexican-American immigrants. And that so many of them were songs made popular by one phenomenal woman: Lydia Mendoza.

Mal hombre,

tan ruin es tu alma que no tiene nombre.

Eres un canalla. Eres un malvado.

Eres un mal hombre.

Here’s a confession: I’m listening to Lydia Mendoza right now, loud enough to warrant complaints from my neighbors. And if you feel the need to lift your chest and bellow barefoot in the kitchen, might I suggest you turn up her first major hit, “Mal Hombre” (“Evil Man,” literally “Bad Man”). It’s my tenth listen this morning and I’m finally learning the words. My favorite part is how her full and slippery vowels creep onto one another so that some lines seem to come out in one impossible, urgent breath. La Alondra de la Frontera, they called her: Lark of the Border.

Born in Houston in May 1916—just a few days before my grandfather across the border—Lydia Mendoza learned to sing and play the guitar from her mother, Leonor. “For me, when I was a little girl, my only toy was the guitar, because it was what I liked the most,” Mendoza said. Her father, Francisco, worked on both sides of the border with the Mexican National Railroad and often took his family with him when he traveled. Lydia remembered reentering at the immigration station in Laredo once, around 1920, when gasoline was poured on her head to rid her of non-existent lice. “It wasn’t just me,” she said. “There were several other children, all Mexicans.”

Once permanently settled in the United States, the Mendozas formed a traveling family band and by the late Twenties were entertaining Mexican and Mexican-American workers throughout the Lower Rio Grande Valley. Surviving on next to nothing, they hitchhiked to areas where migrant workers congregated and sang traditional corridos for meager tips and travel money. In San Antonio in 1932, when Lydia was sixteen, she began to play what would become her signature instrument: the twelve-string guitar. At her request, her father restrung the guitarra doble so the top four pairs were in alternating notes, giving her a distinctly personalized sound. By 1934, she was performing solo sets at San Antonio’s vibrant outdoor market, Plaza del Zacate, where she garnered attention from a local radio station and was invited to sing on-air. After winning the station’s local amateur competition, Mendoza’s popularity began to rise. A few months later, she recorded “Mal Hombre”—having learned the words from a bubble gum wrapper as a child—for Bluebird Records, a subsidiary of RCA Victor. It’s by far her most famous piece.

What is more universal than heartbreak and rage? When Lydia Mendoza sings, nothing. Dramatic, sensual, steeped in longing and pain, this traditional corrido is about a good girl done wrong. In a vein later mined by many blues and country singers, “Mal Hombre” could easily be a Dolly Parton, Loretta Lynn, or Bessie Smith song, if it weren’t in Spanish. It’s such a visceral performance that one need not know the language to understand the song. Her voice is spare and generous as she brings the listener into her agony with the chorus that translates:

Evil man,

your soul is so wicked it has no name.

You are a pig. You are evil.

You are an evil man.

The mosaic of traditional American music is often associated with banjos, bluegrass, and country pickers, or early blues and jazz. Tejano or conjunto-style music is rarely included in the discussion of the quintessential sound of the U.S. But the music of the border is as much a part of the heritage of American folk music as Hank Williams, Robert Johnson, or the Carter Family, and the Tejano sound has existed and evolved for just as long, and dealt in similar themes. Mendoza’s songs were saturated with stories about the darker side of human love, the hardships of working life, and the isolation experienced by the outsider. While her ballads of heartbreak voiced individual, though universal, laments, much of her music reflected a larger sense of loss—that of an entire country—with a relatable austerity.

They took the silver saddle, and Lucerillo, the horse, she sings in “Las Cuatro Milpas” (“The Four Corn Patches”). Two hundred cows, three hundred young bulls, all have come to their end. A typical song about the devastation experienced during the Mexican Revolution, the lyrics in “Las Cuatro Milpas” refer to private land that’s been occupied or destroyed by Pancho Villa’s army. But, like much of the storytelling in working-class Mexican-American culture, the lyrics don’t name the war or focus on the historic figures but rather the attention is on everyday life, on survival. Mendoza’s bleak “El Mundo Engañoso” (“Deceptive World”) exhibits the profound alienation felt by an immigrant in a new land, though no country is named. The location is not what is essential for a migratory population; it is the day-to-day feeling that matters most:

In other times, I’ve found myself in different lands,

and to anyone I could, I did some good,

but now I see that I’m seen as a “nobody,”

and not even worthy of saying “good day” to.

Painful narratives like these, soulfully performed, made Mendoza a central figure for Mexican-American immigrants in the 1940s and ’50s, when the United States was seeing an influx of people emigrating from Mexico as part of the 1942 bracero (laborer) program. Discrimination against Mexicans was extremely prevalent—signs on restaurants and motels read, NO DOGS OR MEXICANS ALLOWED—and Mendoza was giving voice to the disenfranchised. In the age of big band theatrics, it was Lydia Mendoza’s voice and stories that defined her music. “It doesn’t matter if it’s a corrido, a waltz, a bolero, a polka or whatever, when I sing that song, I live that song,” she said. Her unornamented, elemental performances and working-class vernacular earned her a second nickname from her fans: La Cancionera de los Pobres, The Singer of the Poor.

If it was essential to her success that Lydia Mendoza was a representative of the border life, it was also essential that she was a woman. In Mexican culture, women—both mythological and otherwise—tend to play significant roles. From La Llorona to La Virgen de Guadalupe, the country’s history and folklore is packed with iconic female characters. La Llorona, a legend about a ghostly figure that haunts the night wailing for the children she drowned after learning of her man’s betrayal, serves as a warning to both men and children not to wander.

One of the reasons women figure so prominently in the narratives is simply because women are often the ones doing the storytelling. When Mendoza was onstage, she took this type of familial storytelling to the grand level. Her direct way of connecting, constantly asking the audience if they understood, made her an authority figure, while her resplendent Mexican gowns gave the sense that she was a symbol of an entire country. So it’s perhaps natural that Mendoza, performing in the spotlight alone—rare for a female singer at the time—quickly became an almost legendary figure. Although it’s difficult to trace her exact influence, there’s little doubt that her unique sound informed the music of her contemporaries Chavela Vargas, Chelo Silva, Violeta Parra, and later, Linda Ronstadt, Lila Downs, Julieta Venegas, and the late Tejano pop star Selena.

Perhaps because her father did not understand the concept of royalties, Mendoza was paid only a minuscule one-time recording fee for her most popular song, “Mal Hombre.”

“It would not be until decades later that the family realized Lydia had missed out on hundreds of thousands of dollars in royalties,” read her obituary inThe Guardian. Lydia Mendoza died on December 20, 2007, at the age of ninety-one. She recorded more than 200 songs and 50 albums in her lifetime and toured extensively throughout the United States, Mexico, Central America, South America, and Canada. Hundreds of fans traveled to San Antonio for her funeral to celebrate the life and legacy of an American pioneer, more than eight decades after she began performing.

If it seems discouraging that Lydia Mendoza isn’t better known today, it should be heartening to know that she was celebrated and recognized by the greater public within her lifetime. She was honored by Bill Clinton, performed at Jimmy Carter’s inauguration, and was a recipient of the National Endowment for the Arts Heritage Fellowship. There is even a Lydia Mendoza “forever” stamp. And though she sang primarily in Spanish, limiting her audience, she was widely appreciated in her home state. She was inducted into the Tejano Hall of Fame and the Texas Women Hall of Fame, solidifying her last nickname: La Gloria de Texas.

As Mendoza was rising to fame as an icon of the border, my grandfather was changing his name to Frank Charles Limón and becoming an official U.S. citizen. After his mother and one sister died of tuberculosis, he was raised by a foster family (the Hills) and he quickly assimilated into American culture. He went to college, working as a “houseboy” in an upscale sorority house to pay for school. He joined the army, got married, and worked for the Edison Company for thirty-five years. By the time I knew him as my Grandpa Frank, he played golf, drove only American cars, and rarely spoke Spanish. That is, unless he was singing.

When he was singing he’d transform. Head back, barrel-chested, and proud, he seemed more at ease and uplifted when he was singing in his native tongue. You would have thought he was famous. The songs that Lydia Mendoza sang may not have been widely popular among the typical American family, but for Mexican Americans she was a way of staying true to a joint history. Even if the factual details of individual border crossings were lost and muted over time, and the music evolved in performances down the years, the songs remained the same: a way of recognizing the roots of where it all began. After all, the ladder of the American Dream starts at the bottom or, more often than not, the border.

My grandfather’s story isn’t unique or even that unusual. He never became the glory of anything, except maybe his family. But I love that he had an ally through it all, a soundtrack on the radio, a same-aged Mexican-American woman who was more than willing to go onstage for everyone. She might not be immortalized in the same way as other American singers, but that’s only because Lydia Mendoza’s journey to stardom isn’t over. At a time when the U.S.-Mexico border is still rife with violence and Mexican Americans still struggle daily with discrimination, Lydia Mendoza’s musical legacy demands revitalization. In fact, if it suits you, and you’re in the mood to stomp and lift your chest like a force of nature, I suggest you listen to a few of her songs tonight. Turn them up loud and attempt to sing along. What you’ll find in her music isn’t just the voice of a generation, or the voice of an era. It’s the collective sound of a people, rising.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.