On the X

By Gene Fowler

“We was on the radio at Del Rio,” recalls one of the Cowboy Kings in Clem Maverick, R. G. Vliet’s multi-voiced epic poem about the high-lonesome lovesick rise and fall of a country-western singer. “That night Clem yodeled from his toes up. Had to tote him from the mike.” Clem and the Cowboy Kings tore up their tunes as phantoms of a poet’s muse, but their flesh, blood, and whiskey kin conjured their sound into every corner of North America and beyond. Clem’s audience would have known that “the radio at Del Rio” meant one of the high-powered radio stations that dotted the northern frontier of the Republic of Mexico and blasted their signals northward in English from 1930 to 1986. Over the course of those fifty-six years, border radio’s continent-spanning coverage played a major role in popularizing just about every kind of music that came out of Texas: hillbilly, cowboy, gospel, Mexican, Tex-Mex, country-western, blues, r&b, rockabilly, and rock & roll. As ZZ Top’s Billy Gibbons sings in “Heard It on the X,” that’s where many musicians learned their licks.

Border radio’s best-known deejay, a young man from Brooklyn named Bob Smith, who hit the border in 1963 and transformed himself into the mysterious Wolfman Jack, inspired a metamorphosis in 1960s American youth as his late-night howl streaked across the heartland from the Chihuahuan Desert. Listeners—many of whom first heard artists like Lightnin’ Hopkins, John Lee Hooker, and Howlin’ Wolf on the Wolfman’s show—couldn’t tell from Wolfman’s voice if he was black, white, beast, or alien being as he exhorted them to “git nekkid and squeeze mah knobs.”

One listener, the distinctive musician and visual artist Terry Allen, describes a scene that echoes a pioneer West Texas pastime, the ranch dance, when folks would travel long distances to gather and dance to a fiddle band, either in a ranch house with the furniture pushed aside or outdoors. Allen also testifies to the personal impact of border radio, which he wrote about in his song, “The Wolfman of Del Rio.”

“A dozen or so carloads of us would head out to the cotton fields south of Lubbock, loaded down with bootleg beer and whiskey,” the artist recalls. “We’d park in a perfect circle with the headlights aimed in, tune all the car radios to the same station and dance in the dirt. At 10 p.m. or so, we’d tune in ‘The Wolfman’ on XERF out of Del Rio with its massive transmitter in Ciudad Acuña, Coahuila. My private memory of that voice, and what struck deeper and meant the most to me, was listening to it alone in my car on a highway at night. I remember how mysterious it was, and how the music it played was a true revelation,” he told me. “That sense of hurtling through great black empty space, late at night on a dead straight line of asphalt with headlights shining, driving a car as fast as it would go, and listening to the Wolfman on the radio turned up as loud as it would go, is probably where every freedom I value most in my life began.”

Another future Lubbock musician, singer-songwriter and playwright Andy Wilkinson, found the Wolfman so “outlandish, irreverent, irrational in a rational way to my teen brain, and just plain compelling” that he hid in a closet to listen on a transistor until his mom one day discovered him in the secret lair and snatched the radio away, a scene surely duplicated all across America.

Introducing black music to white kids was only one of the cultural borders that was blasted across by the outlaw X. Representing an earlier generation of listeners, black country singer Artie Morris grew up in Temple, Texas, listening to Hank and Lefty on the X. Morris tried to break the Nashville color line in the mid-1950s, more than a decade before Charley Pride appeared on the Grand Ole Opry. “Colonel Tom Parker told me I should just go on back to Texas,” Morris recalls wistfully, remembering the time he stood an infinite twenty feet from the Ryman Auditorium spotlight. In the 1960s, Morris was hired by Buck Owens as a songwriter and wrote tunes like “Country Soul.” In 2001, he released Goodbye Old Paint and Other Trail Favorites, paying tribute to his great-great-grandfather Charlie Willis. Morris’s ancestor had been responsible for inserting the title song, which he’d learned on trail drives, into the cultural record when he taught it to a Panhandle fiddler, who then passed it to fabled ballad hunter John Avery Lomax. Artie Morris returned to his X station roots in 2007, appearing in the Texas Folklife production The Electronic Campfire in Austin, sharing the stage with border radio veteran Dallas Turner, aka Nevada Slim, whom he’d heard on the X so long ago.

Rita Vidaurri, now ninety years old, heard it on the X in San Antonio during the 1930s. As a young girl, she would rise in the middle of the night, tiptoe through her family’s home on Montezuma Street, and tune the “magic eye” of the radio dial, which cast a greenish glow through the darkened room, until the cabinet of sonic wonder crackled forth the faraway magical sounds of station XEW from Mexico City. Before her twenty-first birthday, lovely Rita stood before the XEW microphone herself, establishing a performing career that took her throughout Latin America. But it wasn’t easy for the young Tejana at first. “They called me a pocha, a person who is neither Mexican nor American,” she recalls, the slur’s wound still evident in her voice. “But once they heard me sing, they changed their tune.”

Today, Rita Vidaurri continues crossing cultural boundaries. She celebrated her ninetieth birthday in May with a new CD, recording her first songs in English on three of the tracks, including Willie Nelson’s classic “Crazy.”

XEW, the 250,000-watt Mexico City station Rita listened to as a child, was not one of the American-operated border radio stations. It was owned by Emilio Azcárraga, whose favorite song was reportedly the hillbilly classic of the East Texas Oil Field, Al Dexter’s “Pistol Packin’ Mama.” But young Rita also listened to Lydia Mendoza and other Mexican and Tex-Mex artists on XER, XERA, and XEPN. She might have heard Jimmie Rodgers perform at the grand opening of the first border radio station, XED, in Reynosa, Tamaulipas, in 1930, on a bill with the mariachi group the Border Charros and Mexico’s Nightingale, Rosa Dominguez. The Blue Yodeler returned a year later for re-dedication festivities when the station was bought by his amigo, colorful Houston theater owner Will Horwitz, who inadvertently became the first border radio outlaw when he was sent to the slammer for re-broadcasting the State of Tamaulipas lottery into the United States. He was soon pardoned by FDR.

The true badass grandpa of the border radio industry, Dr. John R. Brinkley, arrived in Del Rio in 1931, establishing border-blaster XER, later called XERA, across the Rio Grande in Acuña. In 1986, when I asked Patsy Montana, the first million-selling female country artist in history (for her 1936 hit “I Want to Be a Cowboy’s Sweetheart”), if she remembered Doc Brinkley, she giggled and said, “Oh, wasn’t he the one with the goat glands?” Indeed he was. The goateed Brinkley, dubbed the “Mystery Man of the Rio Grande” by the Del Rio newspaper, had been run out of Kansas—his broadcasting and medical licenses revoked—for pioneering an early, agricultural version of Viagra in which he slapped thin slivers of billy goat gonads into a man’s scrotum.

I heard Doc Brinkley on the distant X in 1988 when I went to Nashville to promote the book on border radio that I wrote with Bill Crawford. Bob Pinson at the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum played for me a 16-inch electrical transcription disc—a recording device for radio play that preceded magnetic tape—that had just been donated to the museum. It had been found in a smokehouse on the Pickard Family’s Tennessee farm, where it must have sat for decades. On one side of the disc, Doc Brinkley spoke frankly about the mechanisms of human sexuality, and on the other side, the Pickard Family asked America “How Many Biscuits Can You Eat This Morning?” in peppy hillbilly cadence.

The Pickards appeared on the four-hour Good Neighbor Get-Together program on XERA, which also featured the Carter Family, Cowboy Slim Rinehart, and hillbilly vaudevillian Lew Childre. The next year, with the girls Janette, Helen, June, and Anita, the Carters began cutting transcriptions in San Antonio for several border stations. Beth Harrington’s 2014 Carter Family documentary, The Winding Stream, credits border radio as a major factor in establishing their widespread, lasting popularity and importance.

In Littlefield, Texas, Waylon Jennings’s father ran a cable from his truck battery into the house and hooked it up to the radio to hear the Carter Family on XERA. In Dyess, Arkansas, young Johnny Cash heard June Carter’s voice for the first time on Doc Brinkley’s border station. Back in the family’s home state of Virginia, banjo master Dr. Ralph Stanley recalls, the Carter Family and other groups like Mainer’s Mountaineers were received on his family’s Philco, “beaming all the way from Mexico like someone talking to you across the table.”

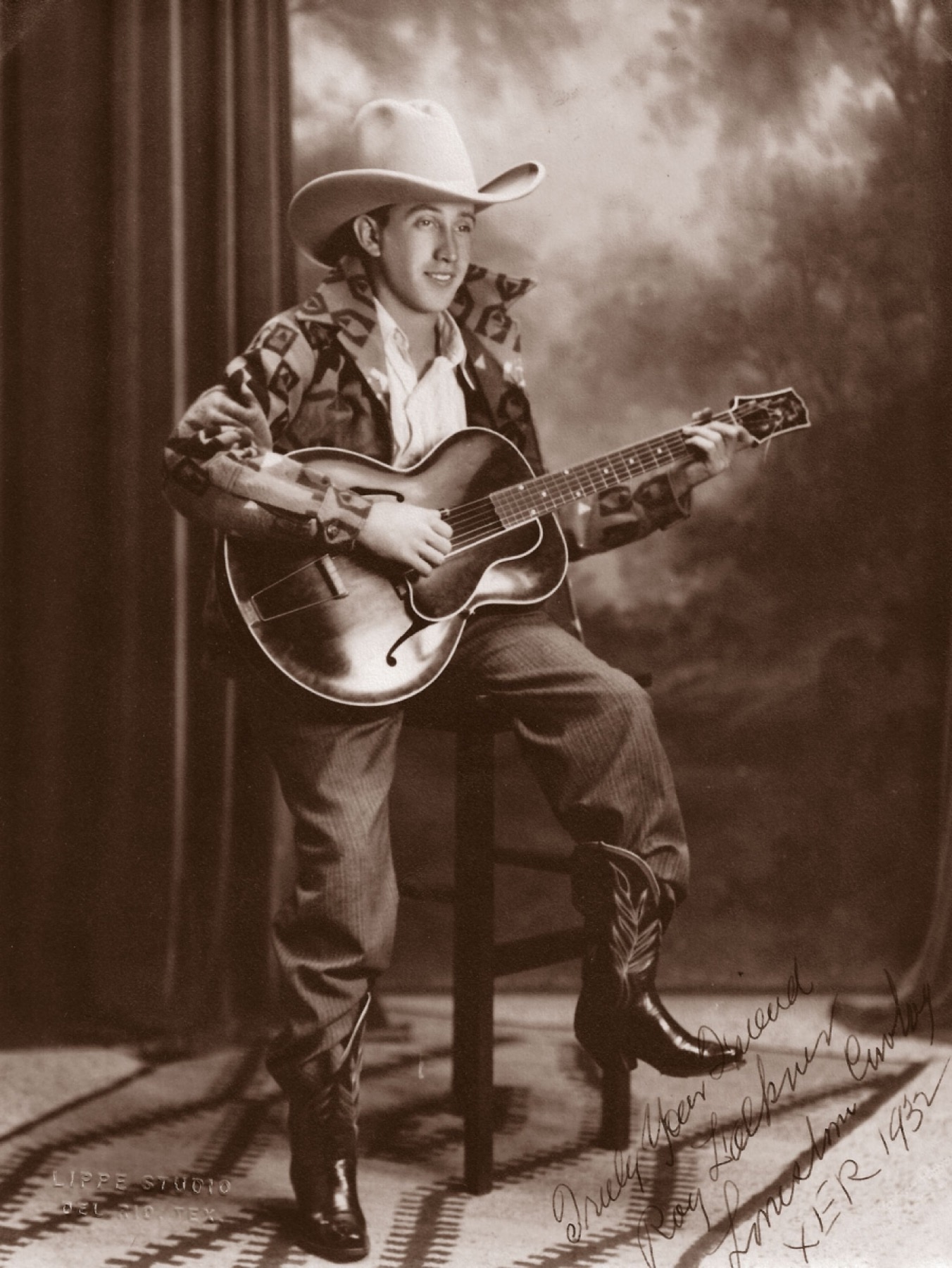

Singing cowboys sold so many songbooks on border radio that some, like Cowboy Slim Rinehart, were reluctant to make records for fear it would hurt their songbook sales. Future broadcaster and honky-tonk songwriter (“There She Goes”) Durwood Haddock, now eighty, sent off for a Cowboy Slim songbook in 1944. “He was my hero,” Haddock recalls. “I listened to him on XEG from Monterrey. We ran a line from our battery-operated radio out to a chinaberry tree at our place in Elwood, Texas, near the Red River. I would sing into a tin cup microphone and play a broom guitar, pretending I was Slim. You can hear his influence on the vocal styles of lots of country artists from the Thirties, Forties, and Fifties.”

Cowboy Slim got in Mother Maybelle’s doghouse once when, on a bender, he lost her guitar in a poker game (though the instrument was soon retrieved). “He was bad to drink,” acknowledged Sara Carter, one of the three members of the Original Carter Family, in a 1978 letter to Rinehart’s protegé Dallas Turner, “but he had a good heart and we sure liked him.” Patsy Montana, who recorded duets with Slim for play on border radio, was surprised to see his widespread fan base when they later toured together through New England.

Growing up in Brownsville, the musician and folklorist Américo Paredes tuned in XERA to hear “the best of the new Mexican music: trios and duetos and so on,” as Paredes related to scholar Ramón Saldívar on his last trip back to Brownsville before his death. When folklorist William A. Owens met Paredes and Paredes’s first wife, the future Queen of the Bolero Chelo Silva, in Matamoros in 1941, where the couple was performing in a cantina, he noted that their rendition of “Cielito Lindo” began as the song is normally performed, then progressed through a huapango, a blues version, and a cowboy yodel. “To them,” Owens wrote in his 1983 book Tell Me a Story, Sing Me a Song, “such a mixture seemed natural on the Border.” Paredes and Silva performed live on XERA in the early 1940s, and Paredes also listened to the station for the hillbilly and western swing sounds, which, he told Saldívar, provided “quite an education in music.”

Depression-era Anglos also broadened their cultural experience by listening to border radio. “I liked the cowboy programs just fine,” recalled one listener who wrote to me in 1995. “But the real highlight of the program was when Rosa Dominguez sang ‘Estrellita.’ To this South Dakota farm boy, that sounded like the angels in heaven.”

After the war, the border stations played a major role in popularizing the hillbilly and cowboy sounds then morphing into country and western. Fifties hit-maker Webb Pierce told me that he didn’t think country music would have survived if it hadn’t been for border radio and deejays like Paul Kallinger, Your Good Neighbor Along the Way, at Doc Brinkley’s former station, reborn as XERF. Although Kallinger would not let Elvis on his all-country show, he did allow an in-studio visit and platter-spin when burgeoning rockabilly legend Ray Campi hit the border with his first record in 1957.

“I’d gone to school in Austin with the Bosquez boys,” Ray recalls. “When I mentioned I’d like to get my record played on that powerful station they said their daddy Ramon Bosquez was one of the owners.” Campi found Brinkley’s Spanish-style station building dilapidated and a little spooky. “It was kind of like a museum, with hundreds of old 78s piled to the ceiling on shelves.” In 2011, Campi released Ramblin’ Ray’s Favorite King Country Stars, a CD of re-recordings of 78-rpm hits on the King label that his cousin had ordered in the 1950s from XERF.

Freddy Fender told me about his own favorite XERF deejay, Howlin’ Rooster, at the 2005 Austin recording session for Los Super 7’s Heard It On The X. “Wolfman named him the Howlin’ Rooster,” San Antonio keyboard player Sauce Gonzalez recalls. “His theme song was ‘Little Red Rooster’ and he’d crow like a rooster when it played.”

Jimmy Pettit, longtime Joe Ely Band bassist and a Del Rio native, says the Rooster booked his Del Rio heavy metal band, Rainbow Hill, to open for early 1970s bullfights in Acuña. “And it was broadcast live on XERF, all the way around the world!”

The last border station, XERF, vanished from the airwaves as Bill Crawford and I were researching our book. Trans-Pecos musicians Jimmy Ray Harrell and Todd Jagger honored the industry’s legacy by naming their twenty-first century band the Border Blasters and for a while broadcast a border-radio style program on Marfa Public Radio.

As Canadian radio fan Murray Lycan recalled, long after hearing his letter read on The Record Roost program on XELO from Juarez in 1969, “That station could not have seemed more exotic to me if they had been on the moon.”

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.