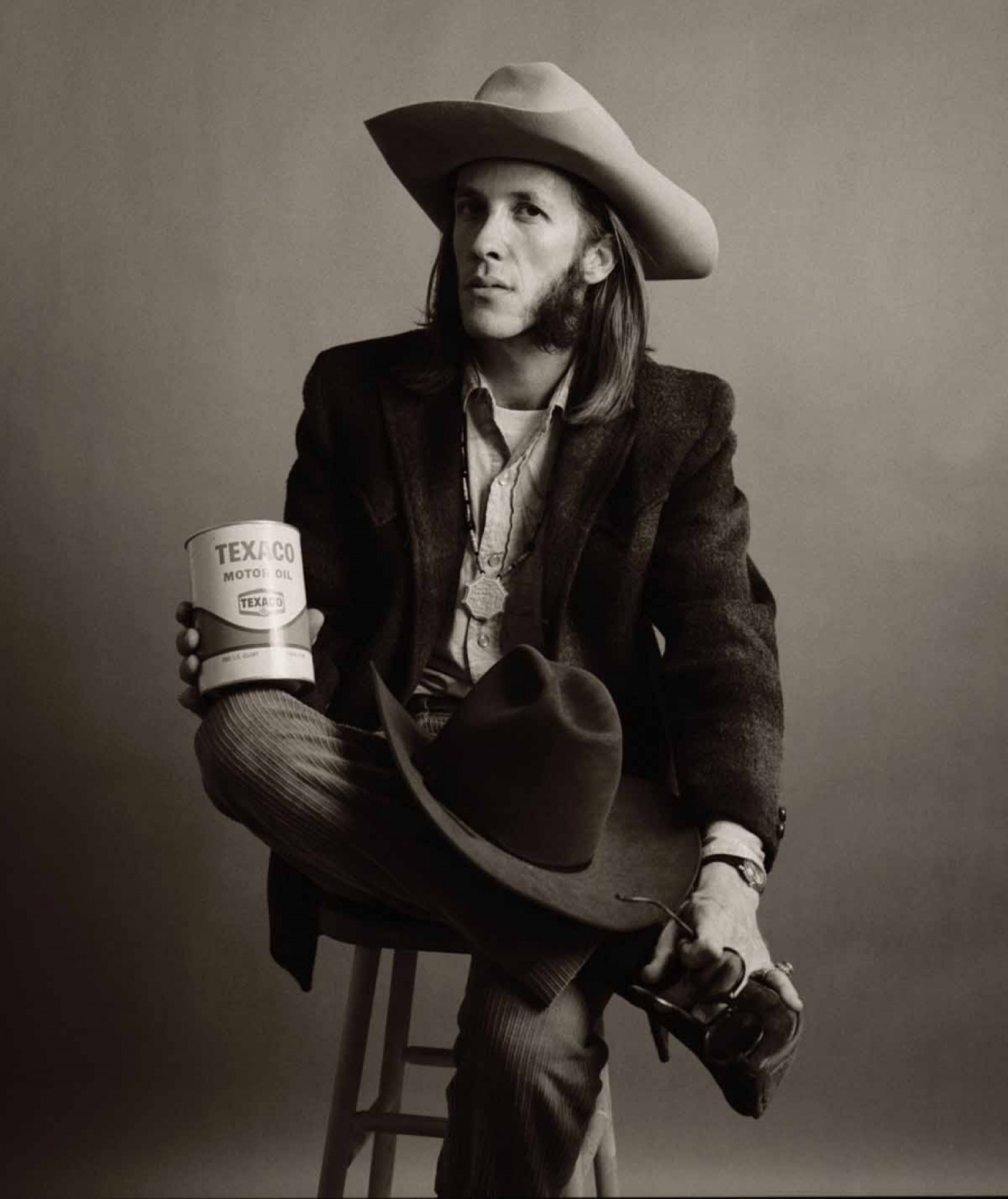

On The Road With the Texas Tornado

By James BigBoy Medlin

The afternoon of June 9, 1973, was hot—not Texas-hot but plenty muggy. Dutch and I sat with our legs dangling over the edge of the stage at RFK Stadium in our nation’s capital. We had just set up the equipment for the Doug Sahm Band. The Grateful Dead and the Allman Brothers were the headliners. But we worked for Doug, and would put his band up against anybody’s. Doug wasn’t as famous as Jerry Garcia or Greg Allman. But they hadn’t shared the stage with Hank Williams when they were twelve. And of course, unlike Doug with the Sir Douglas Quintet, they hadn’t found fame by pretending to be part of the British Invasion while leading a band composed mostly of Mexican Americans. Nor did they have an album out with Bob Dylan on it. Dutch and I figured a crowd eager to hear the Allmans and the Dead would appreciate Doug Sahm.

Ramrod, the Dead’s crew chief, sat down beside us. I didn’t know whether Ramrod was his name or his title. “How many pieces in Doug’s band?” Dutch considered for a second. “If the steel player finishes with Jerry Lee Lewis in time, we’ll have eight. Nine if the fiddler caught his plane out of San Antonio.” Ramrod cracked up. “Man, I remember when we were that loose. That far-out Doug, he’ll never change.”

The gates at the opposite end of the stadium opened. A vibrant herd of 88,000 screaming Deadheads stampeded toward us. We assumed we’d be trampled to death. That seemed okay. The mescaline we had eaten was making us either paranoid or brave. Maybe both. Somewhere, offstage, a roadie tuned a guitar and sang “What a long strange trip it’s been.” We could not have agreed more.

My itinerary over the previous four years had not been planned—at least not by me. I found myself bouncing from Odessa, Texas, to Vietnam to San Antonio to London to Austin. Then things got weird.

In 1972 a tornado blew into Austin, but it was no ill wind. The storm originated in San Antonio, twisted across the country to San Francisco, and flew into Austin at the speed of sound. I’m talking about Doug Sahm . . . the walking-est, talking-est, song-singing-est, guitar-playing-est personification of Texas music to ever pop a top off a Lone Star beer.

Ray Benson, leader of Asleep at the Wheel, is still a big fan of Doug Sahm’s music. “Doug and Willie were the main reasons we headed to Texas in the early Seventies.” As old J. R. Chatwell, one of Doug’s earliest mentors, told Benson: “After I turned Doug on to pot he got on a mental horse and rode off in twenty different directions.” “Meaning,” Benson told me, “he played and sang and wrote blues, r&b, Tejano, rock & roll, jazz, country-western, Western swing, and ‘Sir Doug’—all truly original and inspired!”

When Doug hit Austin, my musically knowledgeable friends were oohing and aahing over him with such reverence that I didn’t want to admit I had never heard of him. Before I knew it, those same friends had moved (dumped) Doug’s band—not into their homes, but into mine. Fortunately the big old house I shared with some other party animals had plenty of room. The rhythm section was upstairs, and the horns were on the ground floor. Doug himself had a nicer house just out of town on the dirt road to Soap Creek Saloon.

Looking back, Soap Creek Saloon turned out to be vital to the development of what is now known as the “Austin Music Scene.” It may have been the last great hippie honky tonk. Everyone from Stevie Ray Vaughan to Willie Nelson to the Sons of Uranium Savages played there. And for a few magical years, Doug Sahm was the King of Soap Creek Saloon! His eclectic mix of Texas sounds found the perfect audience with the educated stoners and slackers who frequented the club. They two-stepped to “San Antonio Rose” one minute, got down to “Papa Ain’t Salty” the next, and then rocked out to a Texanized version of “Honky Tonk Woman.” Doug turned the joint into his own Groover’s Paradise.

The bass player Speedy Sparks once told me that Doug’s arrival changed everything. “When he brought in those San Antonio cats, all the players in Austin realized we had to step it up.”

One night at Soap Creek in the spring of ’73, Dutch Groenewegen offered to stand a round at the bar. In those days, I never turned down a free drink. Dutch had been part of the Family Dog and Avalon Ballroom scene in San Francisco when Doug lived there in the Sixties. Dutch said Jerry Wexler was producing two albums for Doug at Atlantic Records. Even I knew Jerry Wexler had worked with Ray Charles and Aretha Franklin. Dutch and Doug wanted me to go on the road with them. Dutch knew everything about amps, microphones, and instruments. I knew less than nothing. He didn’t care. “All you gotta do is drive. Load and unload. Be my mule. The deal is Doug digs your vibe.”

That’s the way Doug was. He lived by what have become hippie clichés. Good vibes, groovy, going through changes, far out, karma . . . they were road signs he tried to follow.

Before we headed out I confessed to Doug that I had never heard of him before he got to Austin. But that in 1966, while filling out my registration forms at the University of Texas, I heard his song “She’s About a Mover.” I liked his line “She walked right up to me and said ‘Hey bigboy what’s your name?’” So I signed up that way in the student directory, and BigBoy became my name.

Doug said, in that rapid-fire, unpunctuated, staccato style of his, “That’s how it flows with us triple Scorpio brothers . . . We know each other before we do . . . Want to go get a taco . . . Know a joint with far out carne asada . . . Hear how the A’s did last night . . . Man if their pitching holds . . . What you driving . . . Got me an old Lincoln totally cherry . . . Finds my groove when I’m cruising . . . Did you see them comets last night? What a trip! Let’s get straight fire one up.”

And so I became the world’s worst roadie. Little did I know that only six years later my partner Michael Ventura and I would write a movie about the world’s greatest roadie. It was called “Roadie,” and Meat Loaf played the title role. Any resemblances to my real-life roadie experiences were purely coincidental.

Even back in those days equipment trucks for bands like the Stones or the Dead were sixteen wheelers. Dutch and I drove an oversized pickup with a camper covering the bed. Doug’s drummer, George Rains, said it brought forth images of The Grapes of Wrath. We carved out a small area among the gear where one of us could sleep while the other drove. We made it from Austin to New York City without stopping to spend the night.

The album band and the road band were not exactly the same. Bob Dylan did not go on the road with us. Neither did Dr. John, David Bromberg, Flaco Jiménez, or David “Fathead” Newman. But Doug was a master guitarist who could play any instrument. Rocky Morales was a superb sax soloist. And Charlie McBurney could do it all on trumpet. George Rains was “the man” on drums; Jack Barber on bass; Charlie Owens played steel guitar; Doug’s early teacher J. R. Chatwell fiddled and sang; and, of course, Augie Meyers on organ defined Doug’s sound as much as Doug’s own voice. Doug had numerous bands. But Augie was a key component of his two most commercially successful ventures, the Sir Douglas Quintet of the Sixties and the Texas Tornados of the Nineties.

The tour to support the Atlantic albums was not a long one. The band was to play half a dozen gigs with Jerry Garcia’s bluegrass band, Old and in the Way, and one with the Dead and the Allmans in D.C.

While the band was rehearsing in Manhattan, a long-haired dude wearing leather and silver worth more than the band’s equipment came to the studio. He opened his shiny black leather briefcase and tossed a pillowslip-sized bag of cocaine to Doug. “The Dead wanted you and the boys to have this.” Much to my chagrin, Doug thanked the dude and tossed the bag to his manager. I never saw it again. I doubt that Doug ever saw it again either. He was not a fan of coke. In “Give Back the Key to My Heart,” he sings “You’ve got a new friend named cocaine / to me he is to blame / he has drained life from your face / he has taken my place.”

Weed, beer, and coffee were Doug’s most visible vices. The day before the tour started, I was at a table in Doug’s suite. Doug’s bedroom was upstairs. Jerry Wexler entered and introduced himself. “What do you do?”

I replied, “My first assignment every day is to roll twelve joints for Doug before he wakes up.”

“Man!” exclaimed the legendary producer. “Thought I had the best job in the music business, but you’ve got me beat all to hell!” Wexler might have changed his tune when my main task became getting the horn section to the gigs on time.

The music side of things always went smoothly. Old and in the Way was a pleasure to work with, and the crowds in Boston, Passaic, Waterbury, and Philadelphia loved Doug. With so many folks, so far from home, able to recite the lyrics to so many of Sahm’s songs, it amazes me that the Atlantic recordings did not sell better.

When we played Temple University, Dutch had me join him at the mixing board. Usually I was backstage. I had no idea what to do at either location, but was excited to get a lesson on the board. The lesson never happened. Two characters approached the board and said something to Dutch. We immediately moved backstage. Turned out Phil Lesh of the Dead and Owsley, the King of LSD, were doing the mixing. Probably just power of suggestion, but that night’s show seemed more psychedelic than usual.

By then, a big part of my job was getting the horn section to and from the shows. This was delegated to me after Rocky Morales and Charlie McBurney didn’t make it back to the hotel after a gig. Turns out they were locked in the club. They were still sitting at the bar when the owner opened up the next afternoon.

For me, the low point of the trip was after the show at the Orpheum Theatre in Boston. Around midnight, Doug, Dutch, and I went to see one of baseball’s icons, Fenway Park. Doug chattered all the way about the relative merits of Ted Williams and Carl Yastrzemski. When we got back to the hotel, plans had changed. Instead of staying overnight, I had to drive the truck back to New York while the horn section slept on the equipment in back. It was a foggy night and I was groggy. Several times I nodded off and veered onto the shoulder. Somehow I made it to the Mayflower Hotel around seven in the morning only to discover the parking garage was full.

I left the truck in a zone with no parking from 8 a.m. – 10 a.m. The concierge was supposed to call me at 7:45. I woke up at noon. The equipment truck had been towed! That was bad enough, but I couldn’t remember if I had gotten the horn players out. If I’d had the money, I would have caught a bus to Texas. Instead, I told Doug what happened, fully expecting to be shot on the spot. Or at least fired. But Doug just laughed. “New York’s a beautiful place, man, but the slicks don’t cut us no slack. This here’s where the nitty gets gritty!” After a short search, Dutch found the horn players asleep upstairs. We rescued the truck and made it to the show on time.

My favorite part of the odyssey was the show with the Dead and the Allmans. My number one task was getting Rocky to the stadium.

Rocky had on the overcoat he always wore no matter the weather. The pockets were filled with a flask of vodka and several pints of MD 20/20 wine. He hadn’t eaten in two days.

I maneuvered him to a diner and ordered eggs over easy. The scene when the eggs arrived was too predictable to be real. But Rocky really did fall face first into his plate, creating an eruption of egg yolk.

I delivered Rocky backstage. Dutch rewarded me with mescaline crystals from the little leather bag he wore on a chain around his neck. We set up the equipment and sat on the edge of the stage watching the thundering herd of fans. I wondered if Rocky would be able to play.

During the first few numbers he lay back, occasionally honking his sax. Rocky’s big harmonica solo was on a blues tune following a performance by J. R. Chatwell on a Western swing version of “Right or Wrong.”

J. R. was old, but not as old as he and Doug pretended. When Doug introduced him, J. R. hobbled on stage like he was a hundred years old. But when he started fiddling and singing he was a young man again. The crowd ate it up.

Time for the blues. Doug went crazy on guitar, proving he was as great as Garcia and Dickey Betts. Then Rocky took over. He wasn’t standing so well, but he was blowing his face off. The wilder he played, the closer to the crowd he wandered. When he was playing straight down at the outstretched arms, he dropped his harp into the crowd. It didn’t matter. He kept making sounds into the microphone and the Deadheads went berserk!

More things happened that night than I can recount, involving Hells Angels, groupies, dope dealers, celebrities, and of course the music. The Dead’s manager, Sam Cutler, chasing off a police helicopter by shining spotlights on it. The thrill in old J. R.’s voice when he said, “BigBoy, I just smoked a joint with Jerry Garcia!” Garcia inviting Doug to join the Dead, the Allmans, and the Band at Watkins Glen, and Doug saying, “Naw man, too hot in August. And, hey the season damn near over, got to catch some baseball games.”

So Doug Sahm turned down the biggest concert in history to watch baseball. Or maybe it was because he had been out of state most of the year and, in the words of what may have been the last song he ever recorded, he was beginning to “wonder what happened to that man inside, the real old Texas me?”

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.