Old School Poet of the World

By Tamara Saviano

I heard my first Guy Clark song in 1975, on my dad’s turntable at our home near Milwaukee. Dad’s friend had brought a stack of LPs through the door and Guy’s debut album, Old No. 1, was in the pile. While the two of them debated the worth of Memphis soul versus Southern rock, I sat on the floor and planted my ear against the speaker. The lyric sleeve floated on my lap as I tried to listen and read at the same time. I wanted to know everything about the songs that blared out of the box, the four-minute colorful and vivid short stories about exotic people and locations.

My head was filled with questions: Who is Rita Ballou and what is a slow Uvalde? “She’s a rawhide rope and velvet mixture, walkin’ talkin’ Texas texture” was the best line I’d heard in my fourteen years. And that was just the first song on the album. words and music by guy clark was clearly printed beneath each song title on the white paper sleeve—this was when I understood that the man singing had also written these songs. My love for Guy’s poetry introduced me to others like him—Kris Kristofferson, Jackson Browne, and John Prine—bold and eloquent songwriters who place the art and poetry of their writing far and away above any profit-making ambitions or desire to top the pop charts.

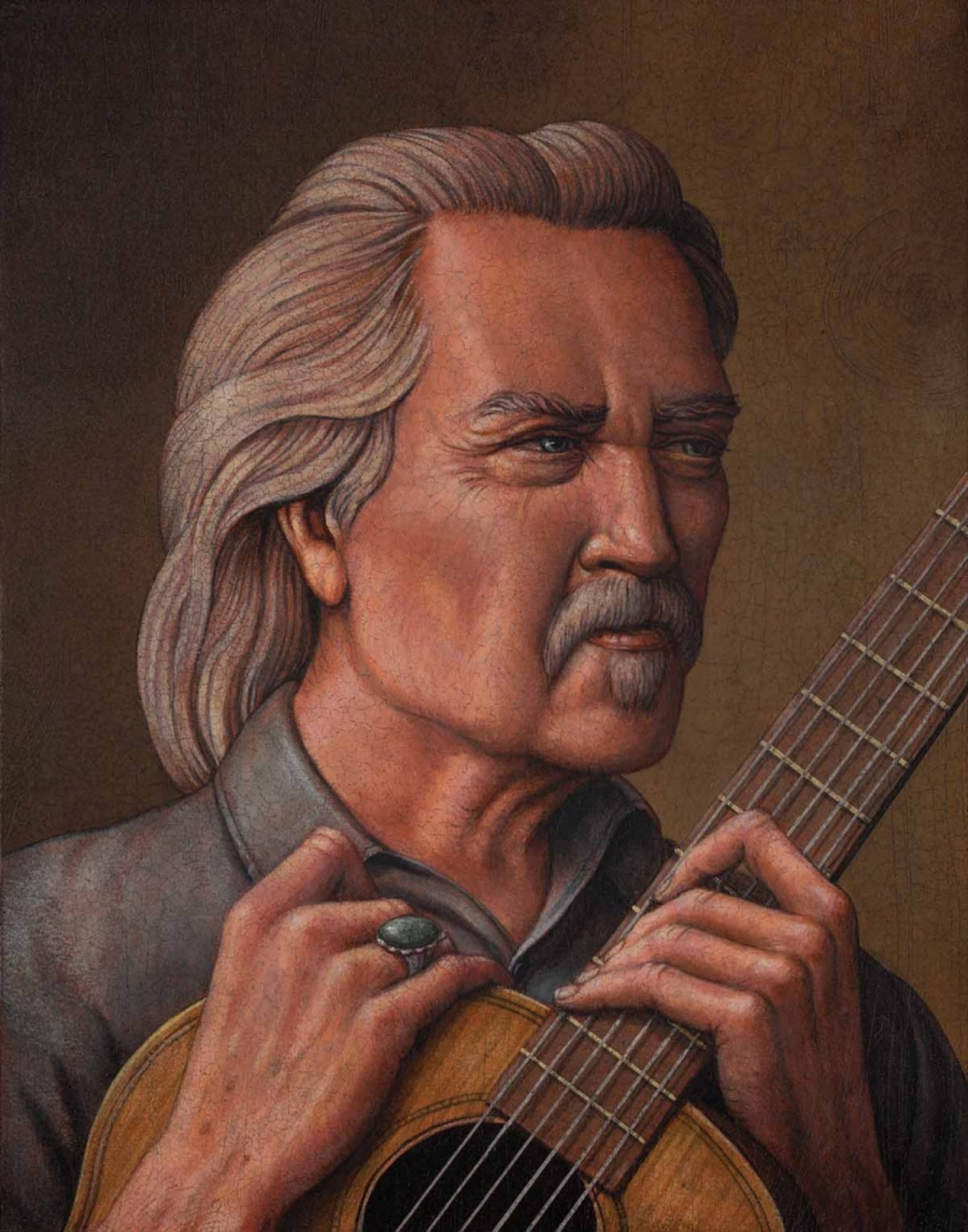

The first time I laid eyes on Guy Clark was twenty years later, in the late Nineties. I was living in Nashville, working as a music journalist at Country Weekly magazine. Dublin Blues had just been released, and I went over to Asylum Records to pick up a copy. As I stood at the reception desk the big glass door opened behind me. I felt his presence before I could even turn around to steal a look. Guy was an imposing figure: tall and solid, size 14 shoes holding up his 6'3'' frame, his hair thick and tousled, and an unlit cigarette between his fingers. A striking turquoise ring flashed from his right hand.

In early 2002, Sugar Hill Records hired me to write the media materials for Guy’s album, The Dark. Though we’d met several times before, for other interviews, when we sat together at a release party for the album I finally got to know him. He was a gallant dinner partner: my wine glass was never empty, he asked what I wanted to eat and placed my order with the waitress, and he stood when I excused myself to the restroom. When we went to a bar after dinner, I drank what Guy drank (numerous glasses of wine and a few short tumblers of Bailey’s Irish Cream on the rocks) and smoked what Guy smoked (we shared a few joints with a few friends). And though it was just another night for Guy, it took me a week to recover.

After that project, I worked again with Guy in 2006 when Dualtone hired me to head up the publicity campaign for Workbench Songs and again in 2009 for the album Somedays the Song Writes You. Both were nominated for Grammy awards.

After nearly a decade of working together, the Center for Texas Music History asked me to consider writing a book about Guy. Since then, we’ve spent hours and hours together as I’ve interviewed him. We even traipsed around Texas a few times in 2010, 2011, and 2012, with him telling me stories of his youth—the childhood he spent in the hardscrabble West Texas plains and his coming-of-age years on the sun-baked beaches of the Gulf in Rockport. And what still always gets me about Guy, even after all these years, is his power as a storyteller. Like the tales he spins onstage at every concert, Guy’s lyrics are part of the fabric of his life as a performer.

Songwriters and music journalists who also admire Guy often comment that his approach to writing lyrics is comparable to his skills as a luthier—that he crafts songs with the same detail and precision of an artisan woodworker. In 1995 Rounder Records even released a thirty-song, double-CD collection of Guy’s songs entitled Craftsman, building on this theme. The title didn’t sit well with Guy, though, who’s told me that craftsmanship and songwriting use two different parts of his brain.

“I should have put a stop to that craftsman shit a long time ago,” Guy says. “It makes my skin crawl. It’s nobody’s fault but mine because I didn’t step up and say, ‘No, that’s not right.’ I consider what I do poetry. I don’t need to prove I’m a poet in every line and I’m not afraid to speak plainly in my songs. Not everything needs to be a metaphor and I don’t need lofty words. But it is my obligation as a poet to be faithful to the verse. I write what I know. I write what I see.”

Being a poet is part of Guy’s DNA. He told me once that he is a descendant of the English poet John Skelton. Skelton was born about 1460 and was poet laureate at Cambridge and Oxford. He was a tutor to Prince Henry and later rose to court poet when the prince ascended the throne as Henry VIII. Skelton wrote at a time when English pronunciation was changing so his peers and mainstream audience often misunderstood his wit and satire. His work simply didn’t fit in with the popular poetry of the era.

The same can be said of Skelton’s descendant. In 1975, Captain and Tennille’s “Love Will Keep Us Together” and the Bee Gees’ “Jive Talkin’” had topped the pop charts. C. W. McCall sang about a convoy while Mickey Gilley had a No. 1 hit over on the country charts with “City Lights.”

Meanwhile, the Monahans native had just released Old No. 1, an album of gritty and dazzling story-songs rooted in the culture of the West Texas desert that, though critically acclaimed, didn’t sell well. Guy wrote these songs between a scarred table at his home—a ramshackle bungalow in East Nashville—and his cubbyhole in a third-floor garret at a publishing company’s old house on Music Row. Sparked by real people and events, Guy’s vibrant narratives brought the colorful characters of his life to the page and immediately separated him from the fluffy pop songwriters of the day.

“Most of the songs I write I couldn’t make up by any stretch of the imagination. They either happened to me or they happened to someone I know,” Guy says. “Like ‘L.A. Freeway.’ It was about four in the morning and I was coming back from a club gig sleeping in the backseat of the car. I woke up to see where we were and said ‘If I could just get off of this L.A. freeway without getting killed or caught.’ Lights started going off in my head with that line, so I got Susanna’s eyebrow pencil and a burger sack off the floor and wrote it down. Then I carried that scrap of paper around in my wallet for a couple of years while the song simmered.”

His other songs were influenced similarly. “Rita Ballou” was inspired by teenage trips Guy took to Garner State Park in Uvalde County. “Texas 1947” is the true story of a streamline train speeding through Monahans when Guy was six years old. And “Desperados Waiting for a Train”—perhaps his most vivid song—is a remembrance of Guy’s earliest male influence, a fascinating wildcatter named Jack Prigg who showed young Guy a world of pool halls and taverns and oil wells that gushed black gold.

“One time I was with Jack when an oil well was blowing out,” Guy says. “They struck oil and it blew the racking board right out—a real gusher. I remember standing next to that rig watching it happen, oil splattering everywhere and the smell, and Jack’s running around in every direction. He did not know what to do. To me, as a kid, Jack was a real desperado, the real deal.”

In “Desperados” the flesh and bone of Jack Prigg is laid bare on the page, as is the admiration and love of his protégé:

He’s a drifter, a driller of oil wellsHe’s an old school man of the worldHe taught me how to drive his car when he was too drunk toAnd he’d wink and give me money for the girlsAnd our lives was like, some old Western movieLike desperados waitin’ for a trainLike desperados waitin’ for a train

Because he wrote this as a poem first and song second, it should come as no surprise that cowboy actor Slim Pickens’s recitation of “Desperados” is Guy’s favorite version of the song.

“That really is my favorite thing anybody has done with one of my songs,” Guy says. “It just gives me chills.”

“Desperados Waiting for a Train” is not the only song of Guy’s that stands alone as a poem. Many of his songs illustrate scenes and people from his life in rich detail—each stanza in perfect balance to the whole. “Texas 1947,” “The South Coast of Texas,” “L.A. Freeway,” “The Randall Knife,” “Stuff That Works,” “Baby Took A Limo to Memphis,” “Dublin Blues,” and “My Favorite Picture of You” are just a few other examples of songs lifted elegantly from Guy’s history.

“Guy is an oral historian and relevant chronicler of life,” says his longtime friend and co-writer Rodney Crowell. “He can sum up a feeling in a word or a phrase. What he doesn’t say is as powerful as what he does say. Pronunciation and inflection are as important as the cultural references. He presents worlds and experiences without judgment or comment and he does it with an evocative style and rhythm.”

Old No. 1 was commercially categorized as country music, and “Desperados” was famously recorded by paragons of the genre including The Highwaymen (Johnny Cash, Willie Nelson, Waylon Jennings, Kris Kristofferson), Jerry Jeff Walker, David Allan Coe, Bobby Bare, and Mark Chesnutt. Yet “Desperados” is really a folk song, inspired by a poem. Guy was deliberate when he sat down to write the poem in stanza form. He wanted to tell the story of Jack Prigg, one of the most important people in his life, and he wanted to write the story as a poem with a simple melody over it. Guy did not write a song to have it played on country radio and gave no thought to what might happen to the song after he wrote it.

Guy swears he can’t crank out cookie-cutter songs even if there is big money to be made. “I’ve had people call and say they need a song like ‘Heartbroke’ for their next album. Well, that’s not how it works with me. I have songs I worked on for years and years before they came to fruition. ‘Baton Rouge’ and ‘Ramblin’ Jack and Mahan’ are two of them. I held on to those songs and tinkered with them because I knew they had good parts but it took me a long time to finish them.”

During Guy’s childhood, the Clark family read poetry together around the kitchen table. Guy was influenced by Robert Frost, who wrote about the life and landscape of New England. He read Stephen Vincent Benét, whose Pulitzer Prize–winning poem “John Brown’s Body” knitted historical and fictional characters to chronicle incidents from the Civil War, as well as Robert W. Service, who illustrated life on the Yukon within his poetry, and Vachel Lindsay, whose dramatic delivery in public readings could be likened to Guy’s modern-day troubadour performances.

Inspired by his friend Townes Van Zandt, Guy began writing his own poetic yet plainspoken songs around 1964 in Houston. The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan had been released a year before. Kennedy was dead and college students all over America were burning their draft cards. The Montrose neighborhood in Houston was a center for the burgeoning counter-culture movement and folksingers were coming together as a scene.

“Townes is the first person I heard who was writing in his own songs in a way that made me want to do it, too,” Guy says. “Not necessarily in his style, but the care and respect he took with writing. He never rhymes moon-June-spoon to make a buck. I’ve always been inspired by Townes. But even with Townes songs, I move around verses where I think they are more poetic. ‘Days up and down they come like rain on a conga drum’ should be the first line in ‘To Live Is to Fly,’ and that’s the way I sing it. Steve Earle gets so mad at me for changing Townes’s song, but I think it works better that way.”

For inspiration, Guy and Townes often listened to the poet Dylan Thomas’s readings of his own work. “Townes and I would think we were hot shit and then we’d put on Dylan Thomas and go, ‘Goddamn, now I see.’”

Photograph of Guy and Susanna Clark with Townes Van Zandt by Jim McGuire, www.nashvilleportraits.com

Photograph of Guy and Susanna Clark with Townes Van Zandt by Jim McGuire, www.nashvilleportraits.com

From the earliest days Guy has written in lined, perfect-bound notebooks. He meticulously laid out his verses in practiced handwriting with No. 2 pencils, shaping ordinary words into extraordinary poetry:

That picture hangin’ on the wallWas painted by a friendHe gave it to me all down and outWhen he owed me tenIt doesn’t look like much I guessBut it’s all that’s left of himIt sure is nice from right over hereWhen the light’s a little dimStep inside this house girlI’ll sing for you a songI’ll tell you ’bout just where I’ve beenIt shouldn’t take too long

The song goes on for many more verses that describe items from Guy’s house: a book of poetry, a glass prism, a guitar, a pair of boots and yellow vest, a leather jacket and bag, a hat.

“Step Inside This House” is the first song Guy put on paper, and the song is an artful peek into his identity and personality. Although Guy never recorded it, the song was shared in and around Houston by fellow folk singers. It was passed around from stage to stage, much in the way Stephen Foster’s “Oh! Susanna” made its way from Pittsburgh to the California Gold Rush in the nineteenth century.

Lyle Lovett finally recorded the song as the title track to his 1998 album, one that pays homage to Texas songwriters. “When we were out on the songwriter tour I’d listen to Lyle sing that song every goddamn night,” Guy recalls. “One night I grabbed him backstage and said ‘Lyle, will you please change that song, man? Leave out this verse and do this and fix this. It’s too cumbersome and people just get bored as shit listening to it.’ I would have fixed it before I played it live and that’s why I don’t play it, because it’s not a finished song.”

“Guy is a ruthless self-editor,” says Rodney Crowell. “I’ve witnessed him come up with the most inspired and beautiful lines, yet he’d throw them out because they didn’t work for the particular song he was writing.”

Even the lyrics on Guy’s albums aren’t always ironclad. He often changes lines years after a song has been recorded to make the song more poetic. “I find better ways to say stuff. To me, the songs are all works in progress,” Guy says. “When I wrote ‘Better Days’ there was a line in it that made my skin crawl. I hated it. I could not think of anything better. Right up to the minute I recorded it, I kept thinking I’d get something better but didn’t so I went ahead and recorded anyhow. The line was ‘On a ray of sunshine, she goes dancing out the door.’ It was just like ‘Goddamn, Guy, surely you can come up with something not that goofy.’”

Guy took the song out of his live set because he could not bring himself to sing the line. Years later, at a gig in Australia, the director of a women’s shelter approached Guy to tell him that the shelter used “Better Days” as their theme song. Guy told her he didn’t sing the song anymore because of the one line he hated.

“And then, the damnedest thing, the perfect line finally came to me right that minute: ‘She has no fear of flying, now she’s out the door.’ It took four years. I knew it was there, but I couldn’t get to it.”

See the wings unfolding, that weren’t there just beforeShe has no fear of flying, now she’s out the doorOut into the morning light where the sky is all ablazeThis looks like the first of better days

The right words are so important to Guy that when Rosanne Cash recorded “Better Days” for a tribute album, This One’s For Him: A Tribute to Guy Clark, Guy called three times to make sure Rosanne sang the new line and not the old one.

Like a poet reading his work aloud, Guy believes that the final step of writing a song is to perform it in front of an audience. He says the song is not finished until he learns to deliver the sounds and rhythms, to learn what to leave in, what to leave out, or even whether the song works at all.

“Poems and songs are living and breathing things,” Guy says. “I can play something onstage for two weeks or two months to just see how it works. You can sit in a room all day long and sing it to yourself and not know where the flaws are. But when you start to communicate it and see if people get it, then you find out where it needs to be fixed.”

Back in the early days in Houston, Townes and Guy practiced their songs at the Jester Lounge, Sand Mountain Coffee House, and the Old Quarter. They also played for fellow members of the Houston Folklore Society, which included the famous blues musicians Lightnin’ Hopkins and Mance Lipscomb. Musicologist Robert “Mack” McCormick once said that Hopkins “is the embodiment of the jazz-and-poetry spirit.” And Hopkins and Lipscomb’s influence on Guy’s writing and performance style is significant. Their influence on Guy laid the groundwork for what was to come of his career later, in Nashville.

After Guy finished Old No. 1, RCA, and then Warner Brothers, did not know what to do with a musician like him. Folksingers had largely fallen under the radar in the late 1970s and 1980s and while Old No. 1 was critically acclaimed, he was working with a major label and the mainstream country radio world and hit records were what mattered most to them. His 1976 release of Texas Cooking and the 1978 album, Guy Clark, were produced with more instruments and polish as the labels in Nashville tried to figure out how to fit Guy Clark into the world of commercial country music.

The style didn’t suit him, and he thought often about Lightnin’ Hopkins, Townes, and the folksingers he had come up with in Houston. Yet Guy went along with the advice of his label. He figured they knew better than he did about how to find an audience and sell records.

If things had gone as originally planned by the label, Guy’s 1981 album, The South Coast of Texas, would instead have been entitled Burnin’ Daylight and produced by Craig Leon. Leon had produced hit records for Blondie and the Ramones in 1976 as well as Rodney Crowell’s 1980 album, But What Will the Neighbors Think? Crowell’s song “Ashes by Now” had recently made the pop charts and the brass at Warner Brothers thought Leon’s approach might spark the same commercial success for Guy.

But Guy and Leon didn’t hit it off. Guy truly wanted to give the label what they needed, but his songs, his poetry, were getting lost in the mix. With little budget left and a deadline for the album looming, Guy turned to Crowell for help.

“Rodney was enamored with Brian Ahern and his mobile truck so we went to Los Angeles to record there,” Guy says. “It seemed like as good a thing as any to do at the time. It was Rodney’s crew and they were all great players.”

But even so, Guy still wasn’t happy with the results of The South Coast of Texas or with his next album, 1983’s Better Days, also produced by Crowell.

“I just didn’t really know what I wanted to do,” Guy admits. “I didn’t like my records after Old No. 1. Some of the songs were badly done and the records didn’t sound like I wanted them to sound. I see myself as a folk singer and my songs as poetry. When there is too much instrumentation the songs get lost.”

For the next six years, Guy practiced singing his songs in front of a mirror in his basement. He wanted to get back to the basics of putting the lyrics in front.

He finally took control of his own recordings when he made Old Friends in 1989, his first record with the noted Americana and bluegrass label Sugar Hill Records. It was a gutsy move at a time when Crowell was having mega-success in country radio with slickly produced albums. Major label country-pop artists—including Reba McEntire, the Judds, Eddie Rabbit, Restless Heart, Alabama, Steve Wariner, and a new guy named Garth Brooks—were riding the Urban Cowboy wave into the next decade, but Guy decided to move in the opposite direction. Old Friends was the first album for which Guy started collaborating with other writers outside of his close circle.

“I really enjoy the nuts and bolts of writing,” he says. “Probably my weakest link as I’ve gotten older is dialing up the ideas. It’s not that my ideas aren’t good; it’s just that I don’t see them like I see other people’s. It’s a strange thing. I’ll get so far into someone else’s three-line idea, when I have probably a hundred times better stuff here and can’t focus like that on it.”

With Old Friends, Guy changed his recording style to complement the verses, parsing sparse musical arrangements to give the lyrics more weight.

This time, Guy went into the studio with just his guitar and co-producer/engineer Miles Wilkinson. He played his songs one after the other, over and over, and ran through them for several days until he got them recorded in a way that pleased him. It was only then that Guy called in other musicians and overdubbed their parts—guitar, mandolin, bass, and a little percussion but no big rock & roll drums. With this understated instrumentation—and for the first time since Old No. 1—the words took a starring role on the album. Guy felt so strongly about this album that the cover itself is a self-portrait.

“Old Friends was the first record where I finally got to make the record I’ve always wanted to make, with an acoustic approach and no drums,” Guy says. “I quit trying to please everyone else in the room and only worried about pleasing myself.”

Guy teamed up with Wilkinson again for 1992’s Boats to Build and 1995’s Dublin Blues, after being courted by Kyle Lehning, who had just opened a Nashville office for the Elektra Asylum label. On these two albums, Guy made an even stronger statement about his commitment to poetry. The songs were written with insight and authority and grown-up themes of hardship, risk, and consequences. All of the arrangements and sounds are in service to the song. Guy re-recorded “The Randall Knife” because he loved the personal song about his father but hated the faster tempo arrangement on the Better Days album. But on Dublin Blues, the heartrending ballad is delivered in the slow cadence of a poetry reading, as a spoken-word song:

My father died when I was fortyAnd I couldn’t find a way to cryNot because I didn’t love himNot because he didn’t tryI’d cried for every lesser thingWhiskey, pain, and beautyBut he deserved a better tearAnd I was not quite readySo we took his ashes out to seaAnd poured ’em off the sternAnd threw the roses in the wakeOf everything we’d learnedWhen we got back to the houseThey asked me what I wantedNot the law books, not the watchI need the things he hauntedMy hand burned for the Randall KnifeThere in the bottom drawerAnd I found a tear for my father’s lifeAnd all that it stood for

Along with “The Randall Knife,” his songs “Stuff That Works,” “Dublin Blues,” “The Cape,” “Boats to Build,” and “Baton Rouge” became instant folk classics.

And this has remained the case for Guy’s subsequent five studio albums. He returned to Sugar Hill Records in 1999 to record Cold Dog Soup, which introduced the first of a series of songs about the true story of Sis Draper, a fiddler from Arkansas known by Guy’s co-writer Shawn Camp. The folk poetry inspired by the tale of Sis Draper include “Sis Draper,” “Magnolia Wind,” and “Soldier’s Joy, 1864,” the last two from Guy’s 2002 record, The Dark.

After Sugar Hill was bought out by Welk Music Group, Guy moved over to the independent label Dualtone Music Group to record Workbench Songs,Somedays the Song Writes You, and, in 2013, My Favorite Picture of You. All three albums were nominated for Grammy awards for Best Folk Album, and My Favorite Picture of You prevailed in 2014. The album includes the final songs in the Sis Draper series, “Cornmeal Waltz” and “The Death of Sis Draper.” The title track is a profound, final tribute to Susanna, Guy’s wife of forty years who died in 2012. As it was in the early years with his subject for “Desperados Waiting for a Train,” Guy’s first intention when writing “My Favorite Picture of You” was to honor his wife within the framework of a poem.

In 2013, the Academy of Country Music awarded Guy Clark its Poet’s Award for outstanding musical and lyrical contributions throughout his career. I was with Guy as he was honored—along with Hank Williams—to join a short list of the award’s previous recipients that includes Merle Haggard, Tom T. Hall, Roger Miller, Harlan Howard, and Cindy Walker.

In 1989, Bob Allen wrote about Guy in Country Music: “He is, in many ways, what Picasso was to modern art, or what the late Raymond Carver was to the American short story: a master of expression and conciseness who has often set the benchmark standards for artistry, originality and integrity in his chosen field.”

Guy makes us taste and touch and feel all the heartache and hope like no one else.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.