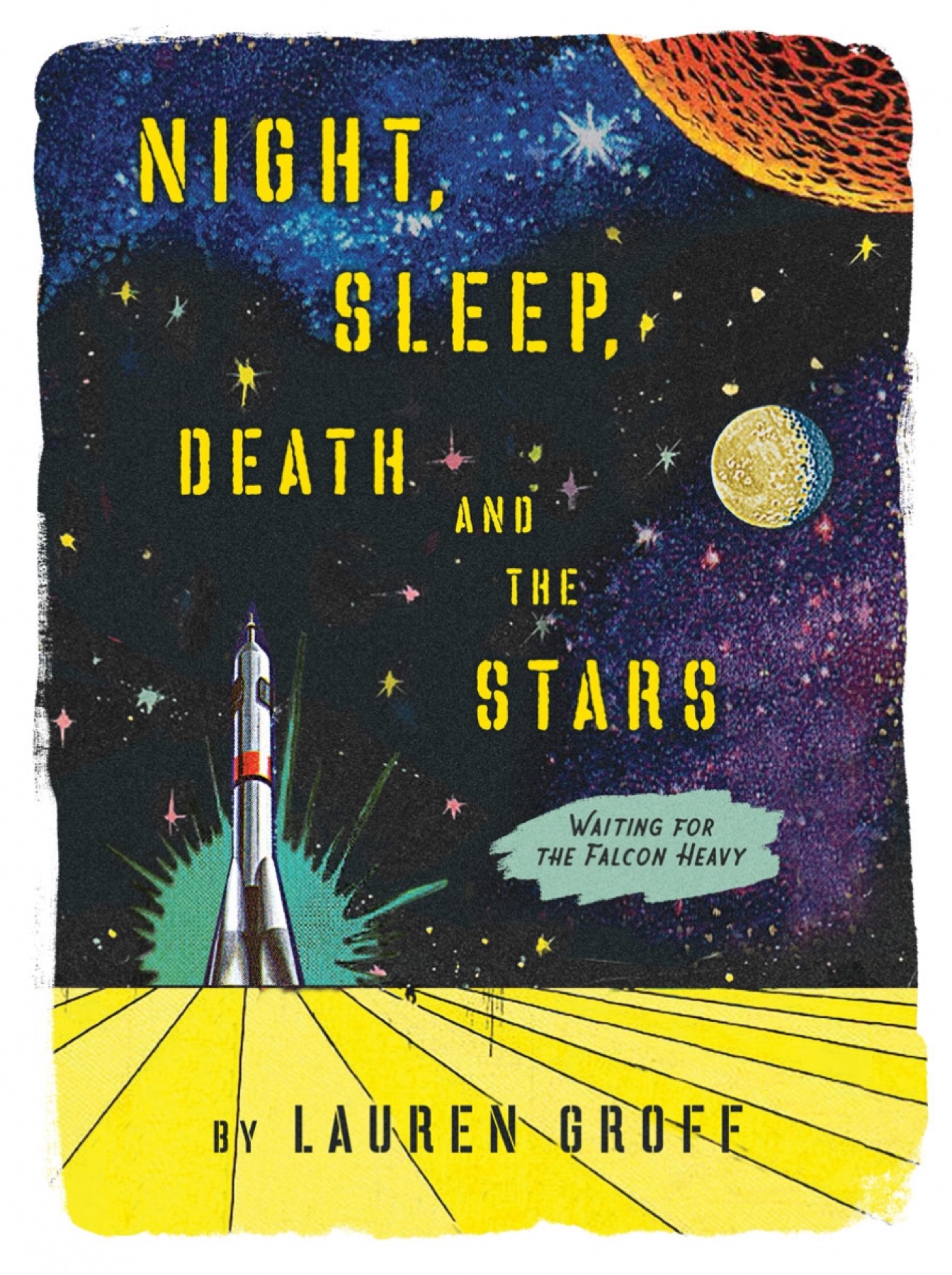

Night, Sleep, Death and the Stars

By Lauren Groff

Waiting for the Falcon Heavy

F

rom across the broad and whitecapped Indian River, the Kennedy Space Center looks like two tiny Lego sets in the distant vegetation. The palms here are windswept, the oaks are scrubby. Pelicans bob in the shallows. Eventually, one of the structures comes clear as a small and skeletal rocket launch tower, the only one visible, though we know more are hidden not too far away. The other is a square block, the Vehicle Assembly Building, where giant NASA rockets are constructed in their upright positions.

It is all disappointingly tiny; but, of course, that is only a wild trick of scale. In fact, the Vehicle Assembly Building is the tallest single-story structure in the world at five hundred twenty-five feet tall, built to withstand one-hundred-twenty-five-mile-per-hour hurricane-force winds. One could fit Yankee Stadium on its roof with acres to spare. The four bay doors through which the shuttles are driven into the Florida sunshine are so vast that it takes them each forty-five minutes to open.

We are speeding along, but it seems to take forever for those distant structures to come near, even when we’re over the river and onto Merritt Island. In the two shining trenches dug beside the road, herons stalk and snaky anhingas spread their heavy wings to dry their feathers in the early sun.

Are we ever going to get there? asks my nine-year-old son.

I say, Maybe!

This was meant to be a joke about our likelihood of Mars colonization, which we had just been discussing. As usual, nobody laughs except for me.

Iwoke my family before dawn for this, scrambling them into clothing and winter jackets, warming their hands with hot bagels for a last-minute January visit to the Space Coast. The night before, it had dipped below freezing in Florida, which always feels like being assaulted by the gods. Cold in Florida feels colder than anywhere else, because one is psychologically unprepared for it. We drove through the dark prairies, still filled with the rains of Hurricanes Maria and Irma from more than a hundred days earlier, and onto the Florida Turnpike (“The Less Stressway”), straight into the rising sun. The dawn was so bright and the clouds were so high and so cold that their edges were crushed in rainbows. From this natural phenomenon we get the word iridescence, after the Roman goddess Iris, whose powers were minor but powerfully aesthetic.

Where are we going? the six-year-old said at last.

We’re going to space! I said. My sons gasped with fear. I mean, I said quickly, the Kennedy Space Center.

Then the boys, who want to be either robot or rocket engineers when they grow up, glowed in the backseat. My husband is a grade-A geek who went to space camp twice when he was a kid, and he began to tell them again about SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy, the most powerful operational rocket ship to date, the launch of which we have all been waiting for and waiting for, but which keeps getting pushed off. The boys already knew about the Falcon Heavy, but they listened to him anyway. It has three reusable rocket cores, the Falcon Heavy! It has twenty-seven Merlin rocket engines in it! It is two hundred thirty feet tall! First there will be a static fire test, which is a full-thrust “wet dress rehearsal” (wet because they burn liquid propellants like oxygen!). When it launches for real, we might be able to see the launch all the way where we live in Gainesville, over one hundred fifty miles away! The boys were rapt.

Space is pretty close to my secular little family’s conception of heaven. It seems to open up philosophy for my husband, who calls it the Colossal Why, and makes him challenge the scale of human life and accomplishment. If we had to choose a living patron saint, three out of the four of us would choose Elon Musk, the founder of SpaceX, a billionaire with the name of a fancy hybrid melon or literary villain. (Not me; I’d pray only to Anne Carson.) My boys have taken a ride in Elon Musk’s Tesla Model X and were gobsmacked by the winglike doors, the trunk space in the front and the back, the power, the self-driving option. They laugh at the pun in the Boring Company, Musk’s deep-drilling business. They love the idea of Musk’s Hyperloop, which is proposed to use vacuum-tube technology to hurtle a train almost frictionlessly between cities. But mostly they love SpaceX, Musk’s insanely ambitious private company that wants to commercialize space for the masses and someday settle a colony on Mars. I can’t escape my suspicion that there’s something penile about the entire concept of a space race, with its talk of rocket erections and thrust and maiden flights, and at these ages there’s nothing my boy children love more than that part of their bodies.

Also, it must be said that my husband is a capitalist and there is something in him built to adore a billionaire.

I am not; I do not. Elon Musk, to me, is a suspect personage.

I explained this in passionate monologue to which my poor husband listened patiently and children tuned out; they’re used to me.

One, I said, it is ethically egregious that even a single billionaire can exist in a world in which children die of starvation every single day.

Two, do we want companies to govern space? Companies are taking over our country, and companies now have more rights than citizens do; companies are stockpiling wealth and diminishing the workforce at the same time. The government is stealing from poor people to feed companies’ greed. The entire purpose of companies is to leach the power of the government, which is to say the entire purpose of companies is to steal the power of the people. And space exploration is supposed to be such a beautiful manifestation of the people’s will!

Three, the idea of colonizing Mars when we are so thoroughly fucking up our own stunning planet—that gave rise to us, that supports our lives, that could, with the slightest modicum of human behavioral modification, support many more generations of life—seems even more morally fraught. Because look!, I pointed victoriously, even in these trenches beside this road where ducks are diving and turtles have come out to bask in what pale sun there is, look at those bits of blown plastic, shining as though they’re innocent.

To this last charge, of the stupidity of using Mars as humankind’s Hail Mary when we could just divert our energy into saving the good blue Earth, my husband just shrugged and said that Musk has a plan to minimize fossil fuel use, too. His company SolarCity is the largest residential installer of solar panels. They’re trying to create solar battery packs to store renewable energy.

Well. Billionaires are still immoral, I said, unable to come up with anything better.

And this is when, with his great kindness, my husband let me save face by asking my children if they’d ever want to go to Mars.

No, I said.

Absolutely, yes, of course, my children said.

At last we arrive. Though we are among the first tourists of the day, people are already posing and snapping photos in front of the great blue NASA globe statue at the Visitor Complex. A digital clock counts down to a pretend rocket launch that thunders the ground every few minutes.

Uh-oh, I say darkly. It’s Disney: Space Adventures.

Yeah! my husband says and convinces us all to leave our coats in the car.

It is a mistake. A bomb cyclone—a vast winter storm—has covered the eastern side of the continent with ice and snow. It’s forty-three degrees out and the wind is blowing off the Atlantic a few miles to the east and it’s Florida, so most of the lines and some of the attractions are outside. But once we’ve entered the park, we all pretend we’re too tough to complain or return to the car to fetch our ski jackets. After all, one week ago, my sons were sledding in negative-seventeen-degree weather in New Hampshire, when a face full of powder can be dangerous.

The overweening narrative of Florida is, among other things, one of constant and oppressive heat. If even Floridians can be seduced by the story, it’s because Florida is an easy state to be suckered into believing you understand. A tourist will come, see a manatee, taste some key lime pie, smell a full-grown man sweating in a Mickey suit on a ninety-eight-degree day, and go back home believing she gets the state. She probably doesn’t. What she has instead is a set of assumptions and punch lines to every other state’s jokes: it’s so full of retirees it’s God’s Waiting Room, it’s so full of theme parks it’s made of plastic, it’s so full of people doing nutty things there’s an internet meme called Florida Man, the most bumbling set of anti-superheroes in history. That day, I’ll notice a story on social media about a man in South Florida who sees frozen iguanas falling from trees. Where he is from, in South America, iguanas are apparently a delicacy. He will gather as many of the stiff gray beasts as he can for a feast and put them in his warm truck and drive home. As he drives, however, the iguanas will all come, horribly, back to life. Although this happened, in fact, in 2010, this man is a Florida Man.

But truth is always more ambivalent, more complicated than the simple narrative, and Florida is no exception. It’s a vast state and a contradictory one, a state in which tomato pickers can live in near-slave conditions not far from a magical kingdom where small children are right now having their minds blown by mermaids and princesses. Salsa dancing and swamps, miles of fading Trump signs and world-class hospitals, alligators and NASA. If I say nobody knows Florida, I mean that there is no single Florida to know. It’s all ambiguous, all so strange. And this place near Cape Canaveral seems the strangest to me, as it helped to give rise to so many of the sophisticated things that I love about modern humanity: cochlear implants, memory foam, cell phones, CAT scans, LED lights, invisible braces, even the laptop on which I will type the final draft of this essay. Yet such fertile ground for modern invention could not possibly look any more humble, all sand dunes with spiky vegetation and teeming masses of wildlife and some scraggly-looking buildings. This place holds its contradiction within itself.

We start exploring the Visitor Complex in the Rocket Garden where retired shuttles stand like great strange tombstones, for children to touch and run around and play in. When we quickly prove too wimpy for the chill, we go back to the beginning, indoors to the Nature and Technology building, where there are both bathrooms and dusty dioramas filled with taxidermied ibises and mountain lions. Cape Canaveral is on the Atlantic coast, midway between Jacksonville and Miami, and it pushes out into the ocean like a muscular arm. Before Europeans came and thoroughly messed with the place, it was populated by the Ais, believed to have been cannibals, and the relatively unwarlike Timucua. Yet the Timucua were still warlike enough to chase off the Spanish conquistador Ponce de Léon, who first landed in Florida near where St. Augustine is today. He called the landmass La Florida, or Place of Flowers. On his next stop he landed near where we are standing, and he called the place Cape Canaveral, after its thick canebrakes.

But Florida, before air-conditioning, was a stark place to live, with its heat and mosquitoes, and it was sparsely populated for the first few hundred years of European colonization. It wasn’t until 1847 that a lighthouse was built on Cape Canaveral. The lighthouse was rebuilt in 1867 as a one-hundred-sixty-five-foot iron-plated structure. A naval Air Force base was created at Banana River in the 1940s, which is why the area began hosting a rocket program in the early fifties. When NASA was formed in 1958, the organization decided to stay in Brevard County, although there was little to no infrastructure there at the time—few schools, no churches, few bridges or roads—and the floods of engineers and their families had to drive over the St. John’s River to Orlando, then pre-Disney, a sleepy little town, to buy anything interesting. In 1961, for its manned lunar flights, NASA bought one hundred twenty-five square miles of land on Merritt Island, north and west of Cape Canaveral. Then the federal government came in and did what it did best, taming mosquitoes and transforming orange groves and building bridges and roads and putting more than two billion dollars into insuring mortgages, building public facilities and schools, shoring up the airports and hospitals, and creating safe harbors and waterways and water systems. Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge was founded, conserving one hundred forty thousand acres of land, water, and swamp and preserving the habitat of endangered creatures, like the dusky seaside sparrow and the sea turtles who climb slowly from the sea to nest on the beaches. Into the swiftly planned and transformed area came a massive influx of educated workers: the population of the county in 1940 was 16,142, and now it is more than half a million. Despite the enormous investment, putting the space program here was a good choice: When shuttles and rockets are launched, because of the rotation of the earth, if anything goes wrong, it goes wrong over the ocean. Plus, the Caribbean offers plenty of places from which to monitor launches.

I will find out later that the dusky seaside sparrow has gone extinct.

I am entranced by reading the history of the area until I finally notice my children sitting glumly on the fake boardwalk, eating the M&M’s out of our bag of gorp. This was not what they signed up for. Enough about the past, I say. Let’s go to Mars!

We are alone in this strange hall, Journey to Mars, which pulsates with red and blue gels and overloud techno music. There are many shiny consoles where all three of my males obsessively try to land pretend shuttles, and kiosks where you can take your portrait in a semi-realistic space suit and email it to yourself. In the corners, actual rovers crouch like afterthoughts: the leggy Athlete, the Sojourner with her solar panels, the Curiosity, the Spirit/Opportunity. All of the rovers look far more awkward in person than I’d imagined them. I am too used to technology meaning sleek design; the hand of yet another billionaire, Steve Jobs, made visible upon the world.

I learn that Mars has two moons, Phobos and Deimos, that its atmosphere is almost entirely carbon dioxide, that a year there lasts six hundred eighty-seven days, and that the planet is red because of the iron in its surface soil. Mars seems profoundly inhospitable to mankind. It seems insane to even visit a place like this, let alone use it as a bank for the future of human civilization.

Out walks a man onto a stage and—made obedient by years of schooling—we all sit to listen. His name is Ken, which is exactly right: He looks uncannily like Barbie’s consort aged into a craggy sixty-year-old man with white hair. The screens behind him fill with wide-eyed evocations of a Mars landing, the mysteries and joys of colonization. When the short film ends, Ken brings the energy. Facts shoot out of him like sparks, so many I can’t possibly catch them all. Ken is a scripted proselytizer and part of his script is to pretend he’s using the screens as a touch screen to make his points. It hurts the heart a little to watch the mistimings, the gestures toward images already gone.

Ken talks of “the search for hope.” He says that “every dollar spent is spent on Earth.” What slowly comes clear is that NASA is ceding a great deal of its authority to commercial interests. It has funded two programs since it shut down its space shuttle program in 2011: the Commercial Resupply Services and the Commercial Crew Program. The Commercial Resupply Services are a series of contracts with companies, including SpaceX, to resupply the International Space Station, which has been in orbit since 1998 and is now on its fifty-fourth expedition. The Commercial Crew Program is designed to prod companies into developing private space technologies for launch into low Earth orbit.

Wait a second, I stage-whisper to my husband, though the music is too loud for Ken to hear me. So NASA isn’t developing anything themselves anymore? They’re just handing out American taxpayers’ money to private profit-seeking companies?

Shush, says my husband. He’s really grooving to Ken’s jam. So are the boys, who nod when Ken asks if they are going to be part of this Journey to Mars, something “harder than anything anyone has ever done.” Something “bigger than they are.” Talk ends. The screens go blank. Ken shuts himself down with the music. He must do this sixteen times a day.

My sons’ sweet faces are filled with excitement. They quiver with it. They stand, ready to personally palpate the endless boundaries of space, and then they nearly fall over themselves to hug a robot that had come out in the middle of Ken’s talk. It’s a man in a glossy plastic suit gliding about on a hidden Segway, but in this place anything can happen and the boys have become true believers. Later they will be crestfallen when my husband, not really thinking, tells them it’s not a real robot but rather a dressed-up man.

Still, we have seen the future, dusty and red and twin-mooned, and it’s not even lunchtime. So we bravely return to the past. A giant orange-and-white stucco shuttle stands before the Space Shuttle Atlantis building, which makes it hard to miss. Up we corkscrew to the top of the building where a movie showing us the Atlantis is supposed to be running, but it’s glitching. So we go to see the shuttle orbiter itself, which is not as big as I’d imagined it would be, for the thirty-three missions it flew and its more than one hundred twenty million miles, before it was retired with all the other shuttles in 2011. It also looks astonishingly and erratically handcrafted, as though my quilting mother, given enough time, could make a shuttle with neater stitches.

The model of the control room is so analogue, no visible computers, that it makes my head hurt to imagine braving space with these joysticks and little metal toggle switches.

I see the chair, or Manned Maneuvering Unit, in which Bruce McCandless made the first untethered spacewalk, and then I see the photograph of him above the upturned blue bowl of Earth, floating far from the shuttle in the airless black of space. I have a mild manifestation of Stendhal syndrome and have to sit down, a quick plunk, on the floor.

This image, I think, is the most beautiful and eloquent visual metaphor for loneliness I have ever seen.

I’m on the floor no longer than a minute before my six-year-old comes over and climbs in my lap and I smell the musky stink of unwashed boy. I hug him and think that I never, never, never want either of my children to go to space, because there is more than enough loneliness here on Earth.

The nine-year-old pulls both of us up and dizzily I follow my boys and we go down a strange slide that demonstrates—what?—a momentary lapse in gravity, perhaps. And then we go into the Shuttle Launch Experience, which is supposed to give the experiencers a mild taste of what it’s like to be in a launch. Up the ramp, televisions run interviews with real-life astronauts, and almost all of them are paunchy and middle-aged and have either Midwestern or Southern accents.

After watching for a while, I say to my husband with wonder, Astronauts are aggressively ordinary.

Makes sense, my husband says. Their lives are a million hours of tedium and three minutes of screaming terror.

With this talk of screaming terror, the boys chicken out. Good; so, they’ll never be astronauts. Some lady volunteers to take them back to the observation room where they can watch us be blown back by what we assume will be something like g-force pressures and laugh at the faces we make. I’m nervous. I hate fear.

But instead of hearing loud noises and being pancaked to our chairs, the fifty or so of us are tipped backward and gently shaken as a rocket pulses upward on the screen before us. Mostly I’m uncomfortably aware of the looseness in my jowls and neck. At the end, we’re tipped forward as though to simulate another lapse in gravity. Above us, doors like the shuttle’s payload bay open wide and on a giant grainy screen above us we can see the spinning Earth. Someone, at some point, had thrown a soda up there. As soon as my husband points it out, I can no longer see the planet, only the brown streaks.

We’re let out, and there the boys are, whole and relieved they didn’t even have to pretend to be in a rocket ship for a few minutes.

The scariest thing about that, my husband says, was letting that stranger lady lead our kids away.

After a lunch of veggie burgers and salads, as ordinary as astronauts, we wait in the chilly wind for what we’re really here for, the bus tour around the launch pads and the Vehicle Assembly Building. Every tourist in Florida has found himself here this morning. And it feels very odd that, in this day and age, many people around us are speaking something that sounds quite like Russian. I try to say this to my husband, but he is fascinated by a man wearing a red fleece, red sweatpants, and white Crocs.

That’s definitely an alien trying to understand earthlings, but who’s not fitting in all that well, he murmurs, staring.

I’m too frozen to laugh. I grab my nine-year-old for warmth and waddle us slowly up to the bus, like an emperor penguin and its chick.

The bus is hot and full; we have to separate. Our guide is Joe and he’s a crusty bugger. He yells at us when we don’t take enough pictures. I like him because halfway through the bus trip, he will announce that he’s a proud liberal; he’ll define it to his captive audience by yelling, Liberal only means open-minded! After that, the hostility will seethe off the man in the camouflage hat sitting ahead of me, and afterward he’ll give Joe a piece of his mind, but Joe will laugh it off.

We pull into the scrub; there’s not much to see at first. Next to me, my six-year-old is asleep. My husband, way in the back of the bus, falls asleep, too. But I’m entranced: Space exploration takes place here! in this motley assembly of corrugated steel buildings, concrete, parking lots, rusted metal thingies, raw wood structures, windsocks, hoses of unidentified purposes, and electrified fences so that the alligators, who can climb, get zapped if they even try. I’m glad to see that the money spent is spent for the raw science of space, not for prettification.

We move around the VAB, where the scale reveals itself when Joe points out the wee little gray mouseholes, which are the ten-foot-tall doors for the people to enter the building. From here, on a huge path of beige Tennessee Alabama River Rock six and a half feet deep, the giant transporters crawl at one mile per hour, bringing the rockets and their umbilical structures from the VAB to the launch pads. Each mile, a transporter burns one hundred sixty-five gallons of fuel. The pads have to be so far away from the VAB and the control building, Joe explains, because no human beings can be within 3.6 miles of a launching rocket. The Saturn V rocket was so loud that it could easily have killed a human standing close enough. The sound can cause your organs to fail.

At last, at last, we’re at the SpaceX launch pad 39A, which we can see through a chain-link fence. The service structure, a tall metal scaffolding upon a built-up beige hill, looks like the skeleton of a sad futuristic robot. The hill contains four stories of hydraulics and control buildings and fiber-optics and power. Beyond, there’s a white globe that is very cute and equally lethal, because it holds the liquid propellants. SPACEX is emblazoned on a water tower as well as on a warehouse-like building.

The tower is there, Joe explains, because just before launch, it releases four hundred thousand gallons of water into what is called a flame trench beneath the rocket. The water absorbs the sound and heat from the explosions. Without it, when the rockets launched, every single window in every town in Brevard County would be shattered.

As we pull away, I understand that I’m deeply, maybe bitterly, disappointed that we won’t be seeing the Falcon Heavy or any SpaceX rocket at all. There was so much excitement in our house, so much discussion. But as it turns out, we have miscalculated our dates by one day. The very next day after our visit, SpaceX will launch the Falcon 9, with the secretive Zuma satellite in it. The Zuma may, or it may not, have failed; SpaceX’s lips are sealed. It’s all so very mysterious.

Elon Musk will say that the Falcon Heavy rocket, the one that thrills my little boys with its size and its power, will be ready to launch by the end of January. Well. We’ll see. We’ll be waiting.

Oh, we are tired, tired to the bones, of all the effortful imagination it takes to consider space and technology. All this ambition, it’s so heavy. We are dumped by the busload into a theater where we stand in the dark to watch a film. I rebel and sit on the floor with my little boy. Maybe I can take a nap. But unexpectedly, I find myself watching with increasing attention. Among the images of the 1960s, skinny men smoking and girls gyrating in tunic dresses, comes the story of NASA.

And suddenly President Kennedy is on the screen, so young and handsome and yellowish with his bright lick of red hair, speaking of how “space can be explored and mastered without feeding the fires of war, without repeating the mistakes that man has made in extending his writ around this globe of ours. There is no strife, no prejudice, no national conflict in outer space as yet,” he says. “Its hazards are hostile to us all. Its conquest deserves the best of all mankind, and its opportunity for peaceful cooperation may never come again.”

And, in the dark, surrounded by strangers, I find that I am crying. Kennedy says:

But why, some say, the Moon? Why choose this as our goal? And they may well ask, why climb the highest mountain? Why, thirty-five years ago, fly the Atlantic? . . .We choose to go to the Moon! We choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do the other things not because they are easy, but because they are hard; because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one we intend to win . . .

I am crying because this is so beautiful, so idealistic, because this is what a real president looks like, because this past year has crushed my ideals under its angry boots. Kennedy’s speech is responding to fear with resolute and clear-eyed courage. It’s making the trip to space a challenge for humanity, and not a competition.

And I’m crying, too, because perhaps, in my fear and anger, I’ve utterly mistaken the foundations of space travel. It’s true that humanity needs to resist something to push beyond its own complacency; this is how we’ve always worked, we weak and oppositional apes. And having money thrown at the starry impossibility of colonizing Mars may give us, as a species, the way to perpetuate life on this ball of soil and water.

Every day, I carry around with me an anguish like an open wound: the knowledge that when I one day leave my little boys, I will leave them with a far worse world and darker future than the one that I was born into. I don’t know if I can forgive myself for the unconscionable act of having invited them, out of longing and loneliness, into this dying world in the first place. Kennedy suggests that maybe, instead of the capitalistic greed and preening and ego-stoking and false catharsis I’ve believed the Mars plans to be, they are, instead, a single blazing point of hope. Maybe they are a large-scale collaborative experiment with all realms of science and engineering, all countries of the world invited to come up with new ideas. Maybe the point is not to make a stupid terrarium on a nasty hostile planet, but to show us the way to fix what we have. Maybe Mars will save Earth.

I am so moved that I can barely see the next film, projected on a screen right above a preserved real-life Saturn Mission control unit. I can barely walk into the warehouse and see the Saturn rocket suspended above, so enormous, seemingly the size of a football field, all that metal to push a tiny glass pill of humans above the atmosphere. Even when we buy the astronaut ice cream, a freeze-dried vanilla sandwich, it can’t bring us back to wonder. We are wondered out. We had intended to go up to see the manatees after all our immersion in space, but we’re all tired, too much information sizzling the neurons into blue sparks at our brains’ edges. So we pile into the car and we drive home, each thinking deeply or not thinking at all. The little boy is certainly thinking because he asks questions: How do people eat on Mars? Can a space shuttle do a back flip? If birds don’t have mouths, how can you tell if they’re happy or they’re sad? Mommy, I forgot, are we driving to somewhere or away from somewhere? The sunset lights up all the grazing horses of Central Florida so their shadows stretch across the highway. We eat dinner at a delicious pizza joint in Micanopy and the boys fall asleep in the car. The dog is ecstatic to see us. The moon is a cold cup when I walk the poor creature through the dark neighborhood. We fall into bed quickly and we sleep soundly and well.

Early in the morning, the six-year-old comes down the stairs and climbs his cold little body into bed with us. We are asleep until he shivers us awake.

I had a dream, he whispers.

Mmmmm, we say, still sleeping.

It was the end of the world, he says.

We’re both awake now but we don’t yet say anything. It is still dark outside and the birds haven’t yet started singing.

There was a rocket, he says. And it was big. Three hundred thousand and six hundred billion of powers. And it tried to launch but it failed. And it blew up the world.

We all imagine this, the great final fireball. The silence goes on and on and on.

Sounds like a bad one, I can finally say. But the little guy has warmed up enough to have fallen asleep again against his father, who is also asleep, and I have said it only to myself.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.