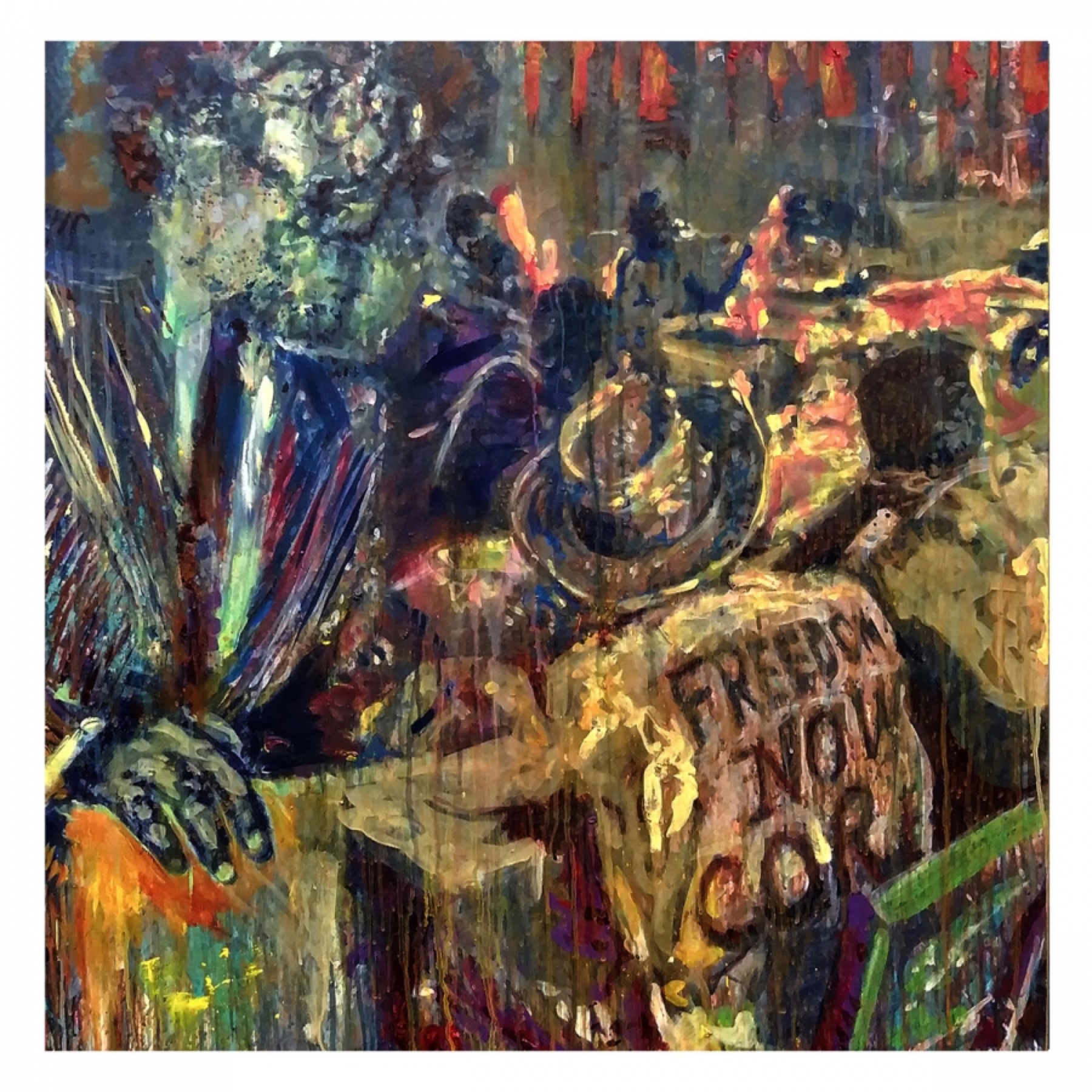

Black Pearl

By Lolis Eric Elie

“New Orleans.”

A concise, intelligible, truthful answer to the question, “Where are you from?”

But that was never the only answer my father gave and seldom the first one.

“Niggertown.”

That was the word he usually chose to begin his origin story. He said it with ironic braggadocio, reveling in its many-splendored layers of accuracy and incorrectness. Really, Niggertown says it all.

It is geography, denoting an area of New Orleans near a bend in the Mississippi River, near Broadway and tony St. Charles Avenue. It is universal in that every reasonably hip city in the world, from Johannesburg to Rio de Janeiro, has its own Niggertown. Any city with a Niggertown must have other neighborhoods contained within its multitudes. So “Niggertown” is interrogatory, too, asking the names of the nigger towns in those cities and inquiring after who lives in them. And who doesn’t.

In the case of my father, it was also a willful incongruence. He used “Niggertown” to make the hearer reconcile the word with the man using it: Lolis Edward Elie, this civil rights lawyer, this man of letters, this collector of fine art and old jazz records, this gourmand, this voracious reader of smart books and drinker of cold Champagne. He could easily have erased the old neighborhood from his biography. But what would be the fun in that? For my father, life began, and would always begin, in Niggertown.

“I yam what I yam,” proclaimed Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, saying in five words what my father said in one.

In 1977, at age forty-seven, my father published “Niggertown Memories,” his one serious attempt at autobiography. The essay appeared in the Black River Journal, a short-lived publication edited by his friend the late Tom Dent. “As far back as I can remember, there has been a continuing argument over whether the community should be called ‘Carrollton’ or ‘Niggertown,’” he wrote. “The people who favor calling it ‘Carrollton,’ almost without exception, are past fifty. When asked why they object to the community being called ‘Niggertown,’ they say, ‘because I am not a nigger and I live here.’”

My father’s insistence on using his neighborhood’s rightful name was part of a battle in his ongoing war against “proper Negroes” and the principles for which they bowed. The concept of the proper Negro can be difficult to understand in an era when hip-hop performers use the word “nigga” with the frequency of a punctuation mark and still win national awards and invitations to the White House. Vernacular culture is the new chic. Such was not the case in my father’s time. In those days, a black person had to act whiter than white and govern his language accordingly if he was to have any hope of achieving the most aspirational rung on the proper Negro ladder: the “respect” and “friendship” of white people.

A proper Negro, upon hearing some white person reminisce fondly about the black woman who “practically raised me,” would express joy at the transracial commonality of black maternity. A Niggertown boy would be more apt to ask, “Who the fuck do you think was raising her kids while she was raising your white ass?”

My father liked to advertise his disdain for the black bourgeoisie. When the occasion was relatively formal, he wore West African attire. Less formal occasions called for his long-sleeved print shirt in the style worn by Nelson Mandela. Informal occasions called for a t-shirt emblazoned with a picture of Louis Armstrong or Cape Coast, Ghana, or some other person, place, or thing relevant to “the struggle.”

However, just like the bourgeoisie, my father liked to eat at fancy restaurants. In the late 1960s, when white politicians were realizing that they needed the votes of the black electorate, a white aspirant for a judgeship invited my father to lunch at Ruth’s Chris Steak House. A white patron walked up to Ruth Fertel, the owner, and said something to the effect of, “If he’s eating here, I’m not.” To her credit, Ruth had a one-word response: “Bye.” In that way my father desegregated the original location of the restaurant that would become the world’s largest fine-dining chain.

My father had a joke that he never tired of telling and I never tired of hearing. Often when dining together at a fancy restaurant, we would be the only black patrons in a crowded dining room. On those occasions, my father would look at me, his only begotten son, and say, “This would be a nice restaurant, but there’re too many black people in here.”

My father came by his bourgeois ambitions honestly. His father, Theophile Jones Elie, was a proud man. Though he could hardly read or write, he was ambitious enough to leave New Roads, Louisiana, for New Orleans, the big city. There he asked his employer, a chemical company, to install a shower so that he could clean up and put his coat and tie back on after his shift as a truck driver. They installed the shower—outside, of course. It was the least they could do. After all, according to family lore, the company had asked my grandfather to set fire to a building, presumably to collect an insurance payment. Family lore does not record my grandfather’s receipt of any proceeds.

If you were the average neighborhood resident, watching my grandfather come and go in his coat and tie and listening to him regale you with stories of his annual trip to see the World Series, you were apt to be so impressed that you might not think too carefully about the sort of work my grandfather did, or the improbability that he never missed the baseball championship.

My paternal grandmother, Mary Elizabeth Villere Elie, scrubbed the white folks’ floors, which is to say that she was a maid. Yet she and her sister always had a beautiful rose garden in front of their shotgun double house on Alvin Callender Street. She balked at the price of the steak dinner at Maison Dupuy, the restaurant my father took her to for her seventieth birthday. But that garden was proof positive that her aesthetic was not constrained by her poverty or geography.

My grandparents shaped my father’s sense of himself and of his world. It would take years for his philosophies to develop and flower, but even as a boy my father’s potential was evident. His sister Doris scrubbed floors to pay his tuition to Gilbert Academy, a quality black private school whose alumni included Andrew Young. There my father appointed himself “head trainer” of the football team, which, by his own admission, was an attempt to lift his status slightly above that of the team’s other water boy.

At Gilbert, he learned that education was of limited economic value to black people. Jesse Blakely, one of the best teachers he ever had, taught psychology, in addition to coaching football and track. But on the weekends, the teacher worked as a porter. So why bother going to college? After graduating from Gilbert, my father took a test to be a galley man on a tugboat and was found to be “sub eligible.” The message: He was not smart enough to wash pots on a tugboat. He eventually got a job as a merchant marine, in which capacity he earned more money than his teachers at Gilbert Academy. College had never been part of the plan. The plan, if there could be said to have been a plan, was to go to New York, to get out of New Orleans.

“Just when I found a good job, they drafted me,” my father wrote in a letter to his mother in 1951. He had just started working as a shoeshine boy in a Manhattan barbershop. In the army, his sense of a “good job” would change. Stationed in California, he became a clerk typist and wrote to my grandmother again, this time saying he had his first “white man’s job.” Even more important than the job was making the acquaintance of Frank D’Amico, a fellow New Orleanian stationed on the same base. Perhaps owing to Frank’s own sense of exclusion from the American mainstream—he was Sicilian—or perhaps because of his basic decency, he suggested to my father that he become a lawyer. That suggestion changed the course of my family’s lives. After leaving the army, my father went first to Washington, D.C., to enroll at Howard University. But when his money ran out, he returned to New Orleans and attended Dillard University. He graduated from Loyola University’s law school. Soon, he would marry my mother, Gerri Moore, and father my sister, Migel. He practiced civil law and rented an office for forty dollars a month. Though he had to supplement his income by teaching GIs, fresh out of law school he hired a secretary, Miss Viola Green, and paid her fifty cents an hour. “She would work four hours a day except on Wednesday,” he told me. “On Wednesday, I decided I would go and play golf for no other reason than that’s what I had seen white people do and I wanted to appear to be a successful lawyer.”

Not long after my father hung out his shingle, the civil rights movement came knocking in the person of Rudy Lombard, a college student on zealous fire with the promise of that crusade. He had seen my father looking stylish and lawyerly on Dryades Street, a black Main Street of sorts. He asked my father to defend him and his fellow sit-in demonstrators. Soon, my father found himself neck deep in the movement in Louisiana and Mississippi.

Particularly harrowing was his work in Bogalusa, Washington Parish, where the Deacons for Defense and Justice, paralleling the example of Robert F. Williams in North Carolina, pledged to shoot back if the Klan shot first. “The tensions in Bogalusa were hot and Governor McKeithen sent in three people to mediate, three white people,” my father told me in a StoryCorps interview in 2006. When they met, my father started by asking the mediators how they all would address each other—with first names or surnames. “We spent a lot of time talking about that,” he said, “and those three white men, they thought that we should get to the substance and not worry about this. I insisted that we resolve that, otherwise there was no sense in having a meeting.”

We all know what happened next. Martin Luther King had a dream. The nation awoke, and a new era of post-racialism had its dawn, right? But for my father, the civil rights movement was the dawn of a new fight, born of his loyalties to the people around whom he was raised. As politicians brandished their civil rights credentials— real and invented—my father asked what these new rights meant for people too poor or uneducated to take ready advantage of them. When his future law partner, Ernest Lake Jones, walked into the Louis A. Martinet Society of black lawyers, he asked for help defending the young men and women of the Black Panther Party. My father alone stepped forward. At the Panthers’ 1971 trial, where they stood accused of attempted murder, among other things, Israel M. Augustine Jr., a black judge, presided. “He did everything he could to get the Panthers convicted,” my father told me with a biting contempt still strong nearly fifty years after the fact. But the jury acquitted the Panthers.

Late in his life, my father surprised me when he became one of Barack Obama’s biggest fans, despite the fact that the president was certainly no “Niggertown boy,” as my father sometimes described himself. Once, the two of us were in a Sonoma County elevator on our way to a friend’s wedding. My father had switched out his customary Panama hat for a baseball cap that said OBAMA: CHANGE WE CAN BELIEVE IN. A large white man, perhaps forty years old, quoting a hackneyed Republican jibe, asked, “How’s that change working out for you?” My father was in his early eighties then. He still had the fire of his youth, but his rhetorical teeth were no longer so sharp. He attempted to mount a defense of his president, but nothing as biting as the Republican mockery came out. I rushed verbally to my father’s defense, but it was too late. Like the night riders of old, the large man had exited before there was much chance of a competent counterassault. President Obama’s re-election was my father’s final word on the matter.

My father surprised me again when, in 2012, at the age of eighty-two, he embarked on a three-week vacation to Paris with his young girlfriend. Since I knew some of the bills would inevitably be put on the credit card we shared, I suggested that two weeks might be a more sensible duration. He would hear none of it. My father was a very serious man and, while it might not be obvious if you were sitting across from him, a wine bottle between you, he often found it difficult to relax and have fun. But when he did relax and have fun, he did it in style. In Paris he stayed at the Hotel La Louisiane, less for fidelity to his home state than for the joy of rooming in the hotel where Miles Davis used to stay. Besides, though he had visited Dakar and Cape Town already, Paris alone could signal how far a Niggertown boy had traveled.

That was my father’s last hurrah. There were other trips but none so long or extravagant. My father was winding down. By 2015, dementia had started creeping in and his lucid moments were fewer in number and shorter in duration. I recorded some of the conversations we had in his later years, but he only showed occasional signs of his previous intensity and wit. I realized that never again would I ask my father, “Were you talking to yourself?” and have him answer, “Yes. Sometimes I like to have an intelligent conversation.”

Sometimes I like to have an intelligent conversation, too. But I’ve lost one of my favorite partners.

As for Niggertown, almost no one calls it that anymore. A friend of mine, a New York native, struck up a conversation recently with an older black man in New Orleans. “What part of the city you from?” my friend asked.

“Well, they used to call it N-Town,” the man said, using a carefully chosen euphemism. “Now they call it Black Pearl. Pretty soon, they’re just gonna call it ‘The Pearl.’”

The first time I heard that, it was a joke. My father was still alive then. Now, with Lolis Edward Elie and so many of his generation no longer with us, the old man’s words were sadly prophetic.

“Nigger” is a controversial word, used more often in its history to denigrate than to celebrate. Putting it in front of the word “town” doesn’t necessarily make it more pleasant. But for my father, Niggertown was a value, a grounding, a declaration of solidarity with those people who scrub floors and drive trucks and pray on their knees nightly that their children will achieve education and success.

The people who live in The Pearl want education and success, as well. But I would not be my father’s child if I did not ask, “Education and success for whom?”

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.