Make It Scream, Make It Burn

In the summer of 1929, after completing his freshman year at Harvard, James Agee headed west to spend a few months working as a migrant farmer. As he wrote to Dwight Macdonald—fellow Exeter alum, longtime friend, and eventual boss at Fortune—he had grand visions for what the summer would hold:

It’s an amusing letter. Agee has never worked, but knows he’ll enjoy it; he has gotten drunk, and he knows he’ll enjoy that too. There’s a sense of manifest destiny in his hypnotic syntax, a grammatical insistence on the fulfillment of desire: I like to . . . and will; I like to . . . and will; I like to . . . and will. He fantasizes about camaraderie and distraction; he wants to be delivered from his own interior life. He’s done too much hard time with too many sonnet writers in Harvard Yard. He wants out. The thing looks good in every way.I’m going to spend the summer working in the wheatfields, starting in Oklahoma in June. The thing looks good in every way. I’ve never worked, and greatly prefer such a job; I like to get drunk and will; I like to sing and learn both dirty songs and hobo ones—and will; I like to be on my own—the farther from home the better—and will.

As it turns out, it wasn’t.

“Kansas is the most utterly lousy state I’ve ever seen,” he wrote Macdonald on “maybe August 1st.” He continued: “Am now working at hauling and scooping grain on a ‘combine’ crew . . . I rammed a pitchfork into my Achilles tendon.”

Agee paints a vivid portrait of himself suffering under the heartland heat—hobbling along a dusty road, raising grain-dusted fingers to put scare quotes around his newly inherited life—but it’s also clear he took pleasure in the hardship he described, or at least he took pleasure in describing it. He signs off: “Have to tackle a load now, Jim.”

At that point in his life, Agee’s manual labor didn’t have much to do with his creative work back home. At Harvard in the fall, he was mainly focused on getting elected to the editorial board of the Advocate, the college literary magazine, and composing dubious love lyrics to his long-distance girlfriend, to whom he was (painfully, it seems) trying to remain faithful: “I murdered joy, that your love might abide;/A precious skeleton lies at my side.”

It was largely anxiety about this girlfriend—and their joy-murdering relationship—that made Agee so eager to work the fields in the first place. “It will be hellishly bad work,” he wrote, “so for once I won’t have a chance to worry and feel like hell all summer.” His letter imagines hard labor as liberation. It’s absurd, of course, but—as will prove an enduring trait—Agee acknowledges his own absurdity before anyone else could possibly call him out on it. He is aware of how naive he sounds as soon as he sounds that way, and hurries to preempt other judgment by judging himself: “I’m afraid it sounds a little as if I were a lousy bohemian and lover of the Earth Earthy, but I assume I’m nothing so foul, quite, as that.”

In this early Agee, we see traces of the later voice: a fascination with worlds far removed from his own; an anguished reeling between judging and valorizing his encounters with these worlds; and an abiding obsession with the relationship between hard labor and interior life: how does feeling reside inside a body that works all day long? Does that kind of brutal monotony banish consciousness? Is it degrading to suggest that it does? To deny it?

The thing looks good in every way: Seven years later, Agee would indict the thing from every angle possible.

Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, Agee’s epic evocation of Southern agricultural poverty, wrestles with the material lives of three sharecropper families in rural Alabama. Researched in 1936 and eventually published in 1941, the book—a piece of sprawling lyric reportage—describes their homes and the necessities of their daily labor, catalogues their clothes and meals and physical possessions, their illnesses and their expenses. But it also forces us into the anguish of Agee’s attempt—as if this attempt were another house, a labyrinthine architecture of its own, its various structures and vectors and approaches and thwarted narratives, built of convoluted syntax and tortuous abstractions; charged by feelings of attachment and—beyond and beneath all—by guilt. The book is exhaustive and exhausting; it is tortured about what it finds beautiful. Sometimes it doesn’t even want to exist. Agee declares at the outset:

If I could do it, I’d do no writing at all here. It would be photographs; the rest would be fragments of cloth, bits of cotton, lumps of earth, records of speech, pieces of wood and iron, phials of odors, plates of food and of excrement . . . A piece of the body torn out by the roots might be more to the point.

He’d do no writing at all, besides the four hundred pages of writing that followed. He hadn’t worked, but knew he’d like it. Now he had worked, a thankless job, and knew he didn’t like what his labor had made, but offered it anyway—because what else could he do? This was what he’d done.

The project of Praise began when Fortune magazine sent Agee to Alabama on assignment during the summer of 1936. He traveled with Walker Evans, whose accompanying photographs would become as famous as Agee’s words. “Best break I ever had on Fortune,” he wrote in a letter. “Feel terrific personal responsibility toward story; considerable doubts of my ability to bring it off; considerable more of Fortune’s ultimate willingness to use it as it seems (in theory) to me.” Evans reported on how this sense of “terrific personal responsibility” shaped Agee’s research: “Agee worked in what looked like a rush and a rage. In Alabama he was possessed with the business, jamming it all into days and the nights. He must not have slept.”

Agee’s doubts about his “ability to bring it off” only deepened once the business itself was done. As he wrote to Father James Harold Flye, a teacher at his Episcopal boys’ school in Sewanee and one of his great lifelong mentors:

Everything there was unpredictable from day to day, I was half crazy with the heat and diet . . . The trip was very hard, and certainly one of the best things I’ve ever had happen to me. Writing what we found is a different matter. Impossible in any form and length Fortune can use; and I am now so stultified trying to do that, that I’m afraid I’ve lost the ability to make it right in my own way.

Agee was on staff at Fortune—outfitted with an office in the Chrysler building where he allegedly went on all-night whiskey benders turning out copy about cockfighting and the Tennessee Valley Authority—but he was right to doubt their “ultimate willingness” to publish. The magazine killed the piece in late 1936.

At this point Agee began looking for other ways to write and publish what he’d found. He applied for a Guggenheim grant, calling his project “An Alabama Record” and describing it as an attempt “to tell everything possible as accurately as possible [with] as total a suspicion of ‘creative’ and ‘artistic’ as of ‘reportorial’ attitudes and methods,” and “therefore likely to involve the development of some more or less new forms of writing.” He didn’t get the grant. Eventually he got a small advance from a publishing house, so he holed up in New Jersey and began expanding his original article into the glorious sprawl that would eventually become Praise. The book was published to little fanfare in 1941, sold about 600 copies—a few hundred more in remainders—and was, in Macdonald’s words, “a commercial failure in every sense.”

It wasn’t until its re-release in 1960 that the book caught fire, fueled by the energy of the civil rights movement and appreciated by a readership primed for the rich narrative texture of the New Journalism. Lionel Trilling would eventually call Praise “the most realistic and most important moral effort of our American generation”—arguing not only for its cultural stature but also for the ways in which it could shift our expectations about what “realism” might mean, and the kinds of messy emotive texture “realistic” might require.

In the meantime, it was generally believed that the original manuscript of Agee’s killed article had been destroyed—or lost for good—until his daughter discovered it in a collection of manuscripts that had been sitting in his Greenwich Village home for years: a 30,000-word typescript simply titled “Cotton Tenants.” This June, the piece was finally published—released by Melville House as a stand-alone text alongside an assortment of Evans’s photographs.

For the first time, we can compare Praise to the husk of its original form. It’s a raw split-screen glimpse into the process of witnessing itself: how does the morally outraged mind begin to arrange its materials? And then—once it runs into doubt, or begins to doubt itself—how does it rearrange them all over again?

In his introduction to the new edition of Cotton Tenants, fiction writer (and lawyer) Adam Haslett lays out the difference between article and book in terms of form:

Let Us Now Praise Famous Men is a four-hundred-page, sui generis prose symphony on the themes of poverty, rural life, and human existence. Cotton Tenants is a poet’s brief for the prosecution of economic and social injustice. The former, as Agee himself tells us, is meant to be sung, the latter preached.

While these formal differences are certainly important—the ways in which Praise deploys more swollen syntax, more convolution, more metaphoric opacity, more soaring upsurges into song—these differences are ultimately symptomatic of a deeper divergence in subject. The article documents, while the book documents the process of documentation itself—and this subtler illumination means its language is serving a different kind of god.

At first blush, it might be tempting to understand these two texts in binary opposition: the unpublished article and the published book, one bound by capital, the other liberated by form—the ticker tape and the prayer, the document and the song. But of course there were no binaries in Agee’s process, only the unfolding and self-frustrated quest to capture what he’d seen, to do it justice—which he knew he’d never do, and which he kept attempting anyway.

In some sense, Praise is nothing but an endless confession—a confession of everything Agee felt and thought and doubted as he tried to tell the story of these Alabama families. We see much of the material in the original article reproduced, but its nodes of physical particularity—descriptions of houses and objects and clothing and meals—are hopelessly enmeshed in the overpowering dilemma of a tyrannical narrative consciousness: Agee’s bottomless but ever-thwarted desire for proximity. Imagine a director’s cut five times as long as the film itself, with the camera constantly turning to gaze at the face of the director himself—explaining how it felt to film each scene, how he’d hurt the actors’ feelings or imagined fucking them, how even the extended film you’re watching now isn’t nearly as good as the one he’d imagined.

In terms of structure, certain differences between book and article are immediately obvious. While the article is organized as a series of chapters devoted to discrete subjects (“Business,” “Shelter,” “Food,” “Health,” etc.), the book has cannibalized these sections with a messier format that both evokes and resists the idea of order. Three “Parts” are interspersed with unparallel sections: “On the Porch 1” and “On the Porch 2,” both cupped by mysteriously unclosed parentheses—as if half-parenthetical, half-included—alongside a section called “Colon,” a section called “Intermission: Conversation in the Lobby,” all of them strange umbrellas for more recognizably titled smaller pieces—“Money,” “Education,” “Shelter”—with the whole thing preceded by several distinct attempts at throat clearing: “Verses,” “Preamble,” “Preface.” This table of contents calls itself “Design of the Book” and the whole enterprise suggests an inescapable self-awareness: this artifact is the product of much anxious hand-wringing about how such an artifact could or should be put together, its various sections are different experiments in this vein, and its refusal to streamline them into consistency is an insistence on making the difficulty of its own construction legible.

“It’s the anarchy of poverty delights me,” William Carlos Williams wrote, “the old yellow wooden houses indented among the new brick tenements.” The “Design” of Agee’s book seems to express this anarchy rather than tame it, allowing sections of different sizes and textures to rub elbows like wood buildings and brick tenements. He describes the effect of poverty on consciousness as a kind of dismemberment—“the brain is quietly drawn and quartered”—and his book feels ripped and reassembled in sympathy. While a glance at Tenants’ table of contents suggests a frame whose rules are already familiar—here are the ways we document—Praise throws up its hands from the start, insisting that all kinds of frames must be deployed and none of them can hold the panorama anyway.

These two texts offer different visions of access: in Tenants, it’s implicit; in Praise, it’s understood as constantly polluted. In Tenants, we sense the physical bodies of Agee’s subjects—wide-eyed and weary, sorghum-stuffed and boil-strewn—but in Praise we have to contend with Agee’s body as well: the clear emergence of an “I” giving us everything we see, and giving it slanted, flawed. We hear about Agee’s emotional relationship to his subjects (“I am fond of Emma, and very sorry for her”); and we hear declarations of personality that often feel gratuitous (“I am the sort of person who generalizes”).Yes, we know. We recognize the Agee who went “half-crazy with the heat and diet,” whose throat and gut protested the food he was served, whose skin protested the bed he was offered. When he describes spending the night with one of his families, sleeping on their porch, he lapses into the second-person “you,” as if speaking to a separate self who slept there:

Waking, feeling on your face the almost slimy softness of loose cotton lint and of fragile, much washed, torn cotton cloth, and immediately remembering your fear of the vermin it might be harboring, your first reactions were of light disgust and fear, for your face, which was swollen and damp with sleep and skimmed with lint, felt fouled, secretly and dirtily bitten and drawn of blood, insulted.

This visceral reeling is typical of the narrative voice in Praise: the speaker as a set of nerve endings, disgusted and disgusted by his own disgust, cataloguing physical particularity anyway—unafraid of banality and repetition in his descriptions (“loose cotton lint . . . torn cotton cloth”); feeling violated by the very place he wants to enter. He feels fouled and faraway at once. We begin the sentence with something external, the texture of linens, and end up deep inside Agee’s own interior life, “insulted,” the declaration isolated at the end of the sentence—a moment of pause, an experiential cul-de-sac.

The shapeshifting “I” of Praise is anticipated by a strange blend of pronouns in Tenants—a “you” that shifts from reader to writer to subject, a grand “we” that tries to include everyone. Agee picks up the sweeping plural of our founding fathers—“if we hold such truths to be self-evident”—and the optimistic “our” of a third-grade textbook—“The world is our home”—in order to implicate everyone in his moral outrage: “We would be merely fools to comfort ourselves with the reflection that the South is a ‘backward’ country.” The “we” is everyone, and the world is our home—its backwardness is everywhere.

Agee’s “you” often works as a kind of imperative invitation. “It’s a very unusual year when you do well with your most important crops,” he writes, making farmers of his readers. Here, he describes a plague of pests: “They web up in the leaves and become flies; the flies lay eggs; the eggs become army worms by the million and you can hear the rustling of their eating like a brushfire.” You can hear them eating, not just can but must—it’s a moral command by way of pyrotechnic sorcery. The fire rages all around you.

Elsewhere, Agee uses “you” to make his readers occupy another position, his own. Observing the sharecroppers’ children, he seems to shy away from the force of his reaction: “You will possibly get the feeling that they carry around in them like the slow burning of sulphur a sexual precocity.” It is, of course, not you but Agee himself who has noticed this “sexual precocity,” but Agee isn’t ready to confess the sexual charge of his own attention, isn’t ready to own the “I” just yet. And when he finally inhabits this “I,” in Praise, he is often punishing it or pointing out its failures.

For all the lyric ferocity and abandon of Praise—its utter shamelessness, its lyric taking-flight—the book’s self-laceration often feels claustrophobic. “I feel sure in advance,” Agee writes, midway through the book and only “in advance” of the second half of its four hundred pages, “that any efforts, in what follows, along the lines I have been speaking of, will be failures.” He stutters over his own words, his faltering commas: there is no way to do this right. He writes the article, it doesn’t run; he writes the book, it doesn’t sell. Agee’s failures call to mind his early optimistic syntax—I like to . . . and will; I like to . . . and will—back when he hadn’t run up against something that blocked his grammar of insistent possibility. In rural Alabama, he confronted a world that refused his capacity. He was enthralled by that refusal; he kept hungering after it.

Part of the claustrophobia of Praise is its suggestion that every strategy of representation is somehow flawed or wrong. It’s a kind of paralysis: what to say, then, if nothing will be good enough? We see an interesting prefiguration of this skepticism in Tenants, where Agee continually imagines other ways someone could react to the same material—defining his own authorial gaze by articulating what it’s not. He spots a tinted photograph of Roosevelt in a frame on the mantel and imagines that a “Federal Project Publicizer” could “flash out some fine copy about the Ikon in the Peasant’s Hovel”; he disputes a “stupid” but widely believed “exaggeration about child labor in the cotton fields”; he describes a “‘rustically’ bent” settee but puts “rustically” in scare quotes. All of these formulations evoke other voices: flashing copy, exaggerating tragedy, romanticizing poverty. Agee uses scare quotes with some frequency, each time accomplishing a defensive tonal straddling—parroting a voice and disputing it at once.

Agee’s points of dispute are telling ones. He wants to establish that his documentary work isn’t doing PR for Roosevelt or his New Deal; he wants to push back against the easy beautification of poverty; he wants to avoid sensationalizing the brutality of agricultural life so that its actual brutality can be better appreciated. Here we find another important difference between article and book: In Tenants, Agee projects problematic reactions onto hypothetical observers. In Praise, he claims them as his own.

Praise discards one sense of realistic documentation—the illusion of presenting truths unmediated and unaltered—and replaces it with another: confessing all mediation, all doctoring. “People want the weight of witnessing without the taint of artistry,” Susan Sontag argues in Regarding the Pain of Others, because artistry “is equated with insincerity or mere contrivance.” In Praise—much more than in Tenants—Agee brutally pushes back against this imperative, exhausting and exposing the taint of his own artistry. He measures the “weight of witnessing” in every way possible.

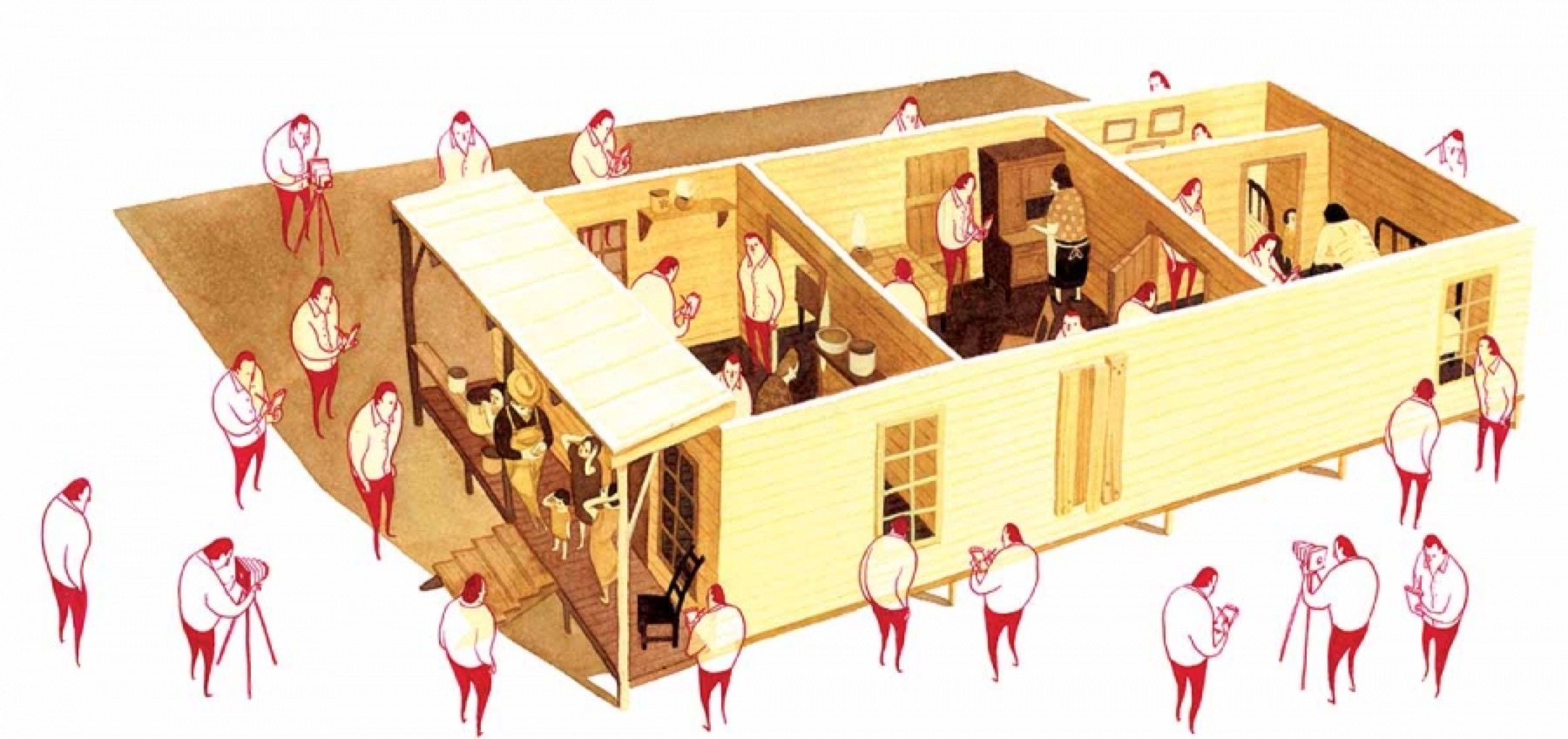

At times, Agee invokes photography as counterpoint—“incapable of recording anything but absolute, dry truth”—though this is just another straw man mythology: all photographs are constructed by framing and selection. Evans was even accused of removing and rearranging objects in the sharecroppers’ cabins, placing rocking chairs in natural light or removing clutter to coax a pleasing austerity from others’ hardship. The cabins were rough drafts that Evans revised into iconic tableaux: a pair of boots standing picturesque on soil, an uncluttered kitchen framed by angled wooden planks, a hanging white washcloth echoing bits of bright light reflected off the glass bulb of an oil lamp.

In a review of Evans’s photographs called “Sermon with a Camera,” William Carlos Williams—who was himself, by his own declaration, “obsessed by the plight of the poor”—praised Evans’s work not for its “absolute, dry truth” but for the ways it summoned universality by drawing eloquence and despair from its raw materials:

It is ourselves we see, ourselves lifted from a parochial setting. We see what we have not heretofore realized, ourselves made worthy in our anonymity. What the artist does applies to everything, every day, everywhere to quicken and elucidate, to fortify and enlarge the life about him and make it eloquent—to make it scream, as Evans does.

Many of the photographs included in the new edition of Tenants are the same as those from the standard 1960 edition of Praise, but they register differently alongside Agee’s sparer reportage: they elucidate more; they scream a bit less. Agee describes the camera as an “ice-cold, some ways limited, some ways more capable, eye” against which his own “I”—ever-frail, ever-fallible, forever discontent—would pursue its own distinct potential: not the prerogative of unstained vision, but the ability to inhabit stained vision as a territory in its own right.

In Praise, Agee maps the stain—Sontag’s “taint of artistry”—by exposing himself as an author disgusted and betrayed by the representational materials he used in Tenants. He rejects the strategies of both narrative fiction (plot, character, pacing) and standard journalism (the illusion of objectivity, the invisibility of the “I”). Agee resists character by suggesting that poverty is “inevitably destructive” of consciousness as we understand it; he resists narrative by continually stressing the monotony of his subjects’ lives—refusing to impose any kind of plotline—and, amid his thousand-and-one metaphors, he suggests the inadequacy of metaphor itself. He wants to turn a broken heart actual: “the literal feeling by which the words a broken heart are no longer poetic, but are merely the most accurate possible description,” but this desire betrays a willful naïveté. Of course “a broken heart” is still poetic, still figurative—or at least, his own is.

Agee doesn’t trust metaphor, but he doesn’t know how to get rid of it either. Describing the departure of Emma—a young married woman to whom he has become attached and attracted, who is moving away with her husband—he gives us a paragraph-long sentence whose layered figurations are willfully elusive in their convolution, receding from comprehension as Emma recedes from sight. We lose Emma just like Agee does. Starting midstream, we find Agee watching Emma’s truck disappear into the distance:

. . . steadily crawling, a lost, earnest, and frowning ant, westward on red roads and on white in the febrile sun above no support, suspended, sustained from falling by force alone of its outward growth, like that long and lithe incongruous slender runner a vine spends swiftly out on the vast blank wall of the earth, like a snake’s head and slim stream feeling its way, to fix, and anchor, so far, so wide of the strong and stationed stalk: and that is Emma.

The closing beat reads like mockery: that is Emma. But what is that? Is Emma the slender runner, the snake’s head, the slim stream, the wide and stationed stalk? Is the stationed stalk the family she’s being removed from? Does her departure hold hope or simply loss? If she is a snake, and a slim stream, and a slender runner all at once—the sibilance itself spreading like a long, lithe thing across the tongue—this heap of figurations suggests a kind of frantic clutching, layer upon layer, as if they will never be enough to bring Emma back—or to settle on the that of who she is, the that of any life.

Complication is a way for Agee to simultaneously indulge beauty and distrust it. So he seeks complication in every sense—from the incongruous “Design” of his book to the gritted convolution of its sentences. He’s damning by excess, and constantly purging it. His eye for beauty turns his stomach.

“Are things ‘beautiful’,” he asks, “which are not intended as such, but which are created in convergences of chance, need, innocence, or ignorance?” In letters he worries continually about his tendency to glorify poverty, troubled by his own “form of inverted snobbery . . . an innate and automatic respect and humility toward all who are very poor.”

Sometimes he confesses this snobbery—“I cannot unqualifiedly excite myself in favor of Rural Electrification, for I am too fond of lamplight”—while at other times he simply enacts it, noticing a “pure white mule, whose presence among them in this magic light is that of an enslaved unicorn” or insisting that “the partition wall of the Gudgers’ front bedroom IS importantly, among other things, a great tragic poem.”

Agee is all sentiment and its backlash. He means his unicorns and doesn’t. No sooner does he admire any house—or the poetry of its partitions—than he calls this admiration into question. Even as he relishes, his syntax apologizes for his relishing: the shrill insecurity of capitalizing IS, the hurried deferral to a larger context of deprivation and practicality (“among other things”), the scare quotes around “beautiful.” And he pushes back against this beauty explicitly as well:

the beauty of a house, inextricably shaped as it is in an economic and human abomination, is at least as important a part of the fact as the abomination itself: but that one is qualified to insist on this only in proportion as one faces . . . the brunt of the meanings, against human beings, of the abomination itself.

Agee wants to insist on the beauty and the abomination at once—oppositional and mutually constitutive—a dialectic that shrugs into compromise: the beauty matters as much as the wretchedness, but no, the wretchedness matters more, but, well, perhaps “in proportion”? Another writer might have resolved this for his readers; Agee refuses.

In Tenants, Agee’s descriptive language doesn’t attack its own lyricism so fiercely. It hasn’t fallen so far from an Eden of uninterrogated metaphor; Agee still savors his virtuosity without fighting it. He describes the flies in one sharecropper house as “a whole drowsing fog . . . struggling and letching on the food, hanging from the mouths and the plastered cheeks of the children, vibrating to death in the buttermilk”; and the food itself is also granted dramatic mortality:

Of the vegetables which began life green, there are few. They are cooked with pork when there is pork to spare; they are cooked in lard when there isn’t; they are at all times cooked far beyond greenness to a deep olivecolored death.

He finds pathos in all the smallest corners and renders it as grandly as he can: dinner isn’t just fatty, it’s sepulchral; collard greens aren’t just fried, they’re martyred. Death is brutal and olivecolored, buttermilk one of its sinister agents.

So while it might be intuitive to assume the lyrical excess of Praise was only possible once the article was unmoored from the financial anchor of Fortuneand its straitlaced aesthetic, this isn’t actually true: melodramatic lyricism was granted plenty of real estate in the original piece. In fact, Fortune generally encouraged a certain brand of metaphoric abandon. Its owner, media magnate Henry Luce, founded Fortune on the belief that it would be easier to teach poets how to write about business than it would be to teach businessmen to write. He hired writers like Hart Crane, Archibald MacLeish, and Ernest Hemingway to fill the magazine’s pages. It seems that Luce’s editors were actually interested in cultivating, perhaps too aggressively, their authors’ ornate prose. Poet James Gould Cozzens resigned from Fortune in part because he was tired of “resist[ing] the editors’ demands for multitudes of similes in each paragraph.” In a private letter, Cozzens made his case against the simile by way of metaphor: “The truth is that a simile is a boob trap,” he writes, not like but is. He specifies: “What it amounts to is that the writer, unable to think clearly enough or write well enough to say what he means, gets around the impasse by cutely changing the subject.”

When Agee stresses that he wants to make sure “the words a broken heart are no longer poetic,” or offers a metaphor so convoluted it seems to lose sight of its object, he echoes this resistance—wanting to avoid the ease of figurative language, the way it deflects the truth or makes this truth too palatable.

If Agee resists the aesthetic strategies of narrative fiction and questions the metaphoric prerogatives of poetry, he openly deplores the strategies of journalism. As the Guggenheim committee already knew, he was “suspicious” of creative, artistic, and reportorial methods alike. Praise offers critiques of many isms—capitalism, consumerism, Communism, optimism—but its critique of journalism feels most pointed. It carries the spurned sense of a child rejecting its absentee parents. “The very blood and semen of journalism,” Agee writes, “is a broad and successful form of lying.” Elsewhere, his critique is more specifically pointed at Fortune:

It seems to me curious, not to say obscene and thoroughly terrifying, that it could occur to an association of human beings drawn together through need and chance and for profit into a company, an organ of journalism, to pry intimately into the lives of an undefended and appallingly damaged group of human beings, an ignorant and hopeless rural family, for the purpose of parading the nakedness, disadvantage and humiliation of those lives before another group of human beings . . . and that these people could be capable of mediating this prospect without the slightest doubt of their qualification to do an ‘honest’ piece of work, and with a conscience better than clear.

Agee’s summation resonates with historian Frederick Lewis Allen’s account of Luce’s belief that “there was money to be made . . . by the sharp presentation of facts, and particularly of facts about America.” But while Praise is still doing exactly what it condemns the journalistic establishment for soliciting—this “parading” of “nakedness, disadvantage and humiliation”—it certainly doesn’t orchestrate this parade with a “conscience better than clear.” It’s in his deliberately muddied conscience, then, that Agee distinguishes himself from the journalistic establishment—and distinguishes his meta-anxious book from its ancestral article. He accumulates moral debt—by writing about a vulnerable population—and then pays it back by confessing his own trespass.

The strong emergence of the “I” in Praise is perhaps less a failure to get outside the self, then, or an unwillingness to grant textual real estate to otherness, than it is a deliberate formal choice to avoid the moral failures of journalism; and this avoidance is perhaps the closest thing to a “plot” that Praise ever attempts or achieves.

The documentary “I” rarely documents without doing some damage. How the Other Half Lives recounts a time when Jacob Riis—one of Agee’s godfathers in the American poverty canon—breaks from civic sermon to make room for a brief revelation of ineptitude:

Some idea of what is meant by a sanitary ‘cleaning up’ in these slums may be gained from the account of a mishap I met with once, in taking a flash-light picture of a group of blind beggars in one of the tenements down here. With unpractised hands I managed to set fire to the house.

This snapshot holds echoes of Agee trying desperately to fight the rising tide of bedbugs; it offers physical fallibility as a sharp reminder of presence and signals the choice to include what could have been easily omitted. Riis published How the Other Half Lives in 1890, just a few years after the emergence of the portable (so-called “detective”) camera, but instead of simply celebrating this new supplement, his narrative confesses a moment in which it seemed like taking these photos might actually destroy what they were trying to capture. We imagine the bumbling witness igniting flashlights on a frying pan and firing cartridges from a revolver, so eager to save these people he almost kills them.

“I discovered that a lot of paper and rags that hung on the wall were ablaze,” Riis continues. “There were six of us, five blind men and women who knew nothing of their danger.” Riis’s confession carries the stink of paternalism even as it admits fault: he makes it clear that he “smother[ed] the fire” himself “with a vast deal of trouble.” He is the agent of trouble, but he’s also the only one who can see it—and the only one who has the power to repair it. He elucidates: he makes it scream; he makes it burn; he puts it out.

Agee never burned down any houses, but his prose betrays a constant preoccupation with the possibility of doing harm—more specifically, with the possibility that his reportage might betray his subjects, the ones whose pain he spins to lyric. He felt the force and peril of his own intrusion.

One of Evans’s photographs shows the sign hanging above a fireplace mantel: PLEASE BE QUITE EVERY BODY IS WELCOME.

Welcome to what? Agee did his best to stay quite. He describes listening to the Gudger family waking at dawn:

When at length I hear the innocence of their motions in the rear of the hall, the noise of the rude water and the dipper, I am seated on the front porch with a pencil and an open notebook, and I get up and go toward them.

It is not going to be easy to look into their eyes.

In some bewilderment, they yet love me, and I, how dearly, them; and trust me, despite hurt and mystery, deep beyond making of such a word as trust.

Here, Agee’s guilt attaches to the “innocence” of his subjects and to the threat of his own pencil—the open notebook like a confession between them—and his invocation of something “deep beyond making of such a word as trust” betrays his fear that trust itself can’t ever apply, and neither can love. No matter the fervor of its framing: “how dearly”! Agee insists upon this intimacy only to confess its shadows: It is not going to be easy to look into their eyes.

If he can’t look into their eyes, Agee wants to do other things to them: he wants to eat their food and sleep on their beds; he wants to “embrace and kiss their feet.” He wants to know them, and understand them, and explain them, to be loved by them and love them back; he even wants—at times—to make love to them. At one point, he imagines having a multi-day orgy with Emma—the young bride who eventually disappears down a long dirt road—and then, inevitably, agonizes over the prospect of this orgy, even though it never happens. He agonizes over what would have happened, afterward, if any of it had happened at all.

But first, he pictures spending whole days with Emma in bed, and—with sporting generosity—also includes Evans and Emma’s brother-in-law George in the fantasy:

If only Emma could spend her last few days alive having a gigantic good time in bed, with George, a kind of man she is best used to, and with Walker and me, whom she is curious about and attracted to, and who are at the same moment tangible and friendly and not at all to be feared, and on the other hand have for her the mystery or glamour almost of mythological creatures.

The orgy is so striking in its own right that it can be easy to gloss over its timing—“her last few days alive”—which seems to suggest the extent to which Agee cannot imagine a different kind of life for Emma, only a different kind of role she might play in his. Agee not only confesses his own desire but also projects this desire onto Emma, imagining what she thinks of him—the amusing shade of humility in placing almost before “mythological creatures” (who would no doubt need a larger bed)—and grounding all these theories in “subtle but unmistakable expressions of the eyes, or ways of smiling” that he believes Emma has offered him.

For Agee, this orgy not only represents an alternative to grim procreation (he calls every sharecropper conception a “crucifixion of cell and whiplashed sperm”) but also a consummate journalistic closeness—subject and object of the portrait finally joined. Agee fantasizes that this consummation could grant Emma, cloistered and degraded by circumstance, some liberty and bliss: “almost any person, no matter how damaged and poisoned and blinded, is infinitely more capable of intelligence and of joy than he can let himself be or than he usually knows.” Sex represents the ultimate access; it resurrects capacity, it blooms against damage. But sexual intimacy summons its opposite: the peril of bodily defilement. It’s no mere coincidence that Agee found deception in the semen of journalism. If the orgy is a fantasy of reciprocity and closeness, then journalism is more like onanistic spillage, an observer getting off at the expense of his subject.

There are moments in Tenants where Agee imagines a masturbatory relationship to the aesthetic appeal of poverty: a family Christmas that “would warm the cockles and, very possibly, the ventricles of any good Dickensian”; or “a tin-framed mirror over which certain fanciers of the antique would have nocturnal emissions.” In Tenants, though, it’s always other people—hypothetical observers—who are getting off in the wrong way; it’s in Praise that Agee finally confesses his own sexual investments. The “you” of Tenants—who will “possibly get the feeling [of their] sexual precocity”—has become an “I” who imagines having a “gigantic good time in bed.”

When Agee finally does spend a night at the home of his subjects, it’s not much of an orgy: “I tried to imagine intercourse in this bed,” Agee writes, and, unsurprisingly: “I managed to imagine it fairly well.” He continues: “I began to feel sharp little piercings and crawlings all along the surface of my body.” His sexual imagining gives way to another kind of bodily experience—something closer to the “insult” of violation, an orgy in which he, rather than one of his subjects, is the one being preyed upon.

Imagination and insult are never far apart for Agee; the latter haunts the former as guilt and specter. After the orgy, he knows, everyone would still be separated by the old subject-object divide—and Agee can’t bring himself to imagine the “gigantic good time” without imagining what would happen once it finished: “how crazily the conditioned and inferior parts of each of our beings would rush in, and take revenge.” As with many of his abstractions, it’s not entirely clear what Agee means here, but his phrasing acknowledges that whatever an orgy could provide (temporary closeness, fleeting pleasure) would inevitably be succeeded by the betrayal of returning context: Agee would once again be the journalist, Emma would once again be the subject; they couldn’t stay in bed forever.

In other words: no matter how deeply or effusively the writer fantasizes about making love to his subject, he will always end up fucking her.

Janet Malcolm has become famous for her own articulation of a kindred angst at the beginning of The Journalist and the Murderer:

Every journalist who is not too stupid or too full of himself to notice what is going on knows that what he does is morally indefensible. He is a kind of confidence man, preying on people’s vanity, ignorance, or loneliness, gaining their trust and betraying them without remorse.

Writers who document poverty face a particularly thorny version of this dilemma. The power imbalance looms large when the subject has no means—is only, as it were, the means to an end—and the journalist finds himself with many things to confess: sins of betrayal, misrepresentation, misdirection, omission, invention, and apathy. Is there any alternative to an abiding sense of culpability?

William Vollmann roamed the globe asking poor people why they were poor, and wrote a book about what he found, but he claims the whole thing didn’t make him feel guilty: “I cannot claim to have been poor. My emotion concerning this is not guilt at all, but simple gratitude.” He paid his subjects and admits it. He probably didn’t pay them enough to change their lives in any meaningful sense, and he admits that too. Vollmann has consistently sculpted his public persona from the grit of immersion and confession: he lets homeless people set up camp in the lot outside his writing studio; he frequents prostitutes; he does hard drugs; he does hard drugs with prostitutes; he does hard drugs with the people he writes about; he breaks into factories and rafts down polluted rivers and never tries to disguise the deeply flawed and distorting terms of his subject relations. He claims not guilt at all—not about poverty, or his privilege, not like Agee, who he claims “carries his sincerity to the point of self-loathing”—but elsewhere we see that Vollmann lives under the shadow of guilt as well. When asked to explain his “preoccupation with the marginal and downtrodden,” he told an interviewer:

When I was a young boy, my little sister drowned, and it was essentially my fault. I was 9, and she was 6, and I was supposed to be watching. I’ve always felt guilty. It’s like I have to have sympathy for the little girl who drowned and for the little boy who failed to save her.

Agee wants to purge the shame of his privilege; Vollmann wants to exorcise the ghost of his own culpability. When Vollmann asks a Thai prostitute named Sunee, “Why are some people poor and some people rich?” she brings up another kind of ghost. “From the life before,” she says. “If you do a good thing you won’t be poor.” The logic floats above, unspoken: but if you do a bad thing, you will be. If you are poor, that means the bad thing was done. It must have been. Guilt hovers everywhere—from everyone—seeking to attach itself to anything; because it makes sense of, constructs some kind of order. It implies causality and culpability and—in these—agency, power.

Vollmann calls Praise “an elitist expression of egalitarian longing.” He calls it “an outcry of childlike love, the love which impels a child to embrace a stranger’s legs.” He says it “falls repeatedly on its sword. It is a success because it fails. It fails because it consists of two rich men observing the lives of the poor.” He finds something pathetic about the ferocity of its desire, and its fantasy of intimacy, in its apology to those it documents, and in the “gorgeousness of [its] abasement.” Perhaps the job of the rich man writing about the lives of the poor is simply to fail as best he can. Vollmann says of himself: “I’m left with nothing to honorably attempt, but to show.” What else can the writer do? How can he reconcile himself to everything he can’t do, all that showing leaves unchanged?

Jacob Riis once sat in a city-planning meeting while a builder named Alfred T. White insisted that more humane apartments could be constructed without raising rental fees. “I wanted to jump in my seat at that time and shout Amen,” Riis wrote. “But I remembered that I was a reporter and kept still.” He wrote The Other Half instead. It was his way of trying to make the world a place that could deserve an Amen—a way to say we must, an accusation and an exhortation, a prayer directed at the entire city.

Praise is a prayer but it’s also an admonishment. To read Praise, Vollmann concludes, “is to be slapped in the face.” Agee wasn’t just thinking about himself—his own guilt, his own love, his own arms flung hopelessly around his subjects—he was thinking about you, reading his words, what you could see and what you couldn’t. He wanted to throw a pile of excrement on your open notebook and let you figure it out. The dilemma of impotence—the quest to keep speaking, and the inability to ever say enough—is one of Agee’s great legacies. It choked and spurred his speech. But Agee’s legacy wasn’t just the sublime articulation of futility. His legacy wasn’t just journalistic skepticism, it was the attempt to find a language for skepticism and to rewrite journalism in this language. In the 400-odd pages of Praise, we find a lot of guilt; but we also find a lot of research. Tenants helps us remember this.

Now we can witness what Agee made first, and we can examine it alongside the epic it became once it got digested by the organs of an endless self-loathing. We have the first failure in a long line of failures—all of them filled with rush and rage, all of them beautiful. We have the first record of eloquence before it learned to scream. Tenants summons a you, and extends an invitation: You can look. You must. Look at what Agee wrote when he remembered he was a reporter, and wouldn’t keep still, wouldn’t keep quite. Look what happened when he sought an Amen, and found these words instead. Now look closer. You can feel him getting restless. You can hear the rustling of his guilt like the beginning of a brushfire.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.