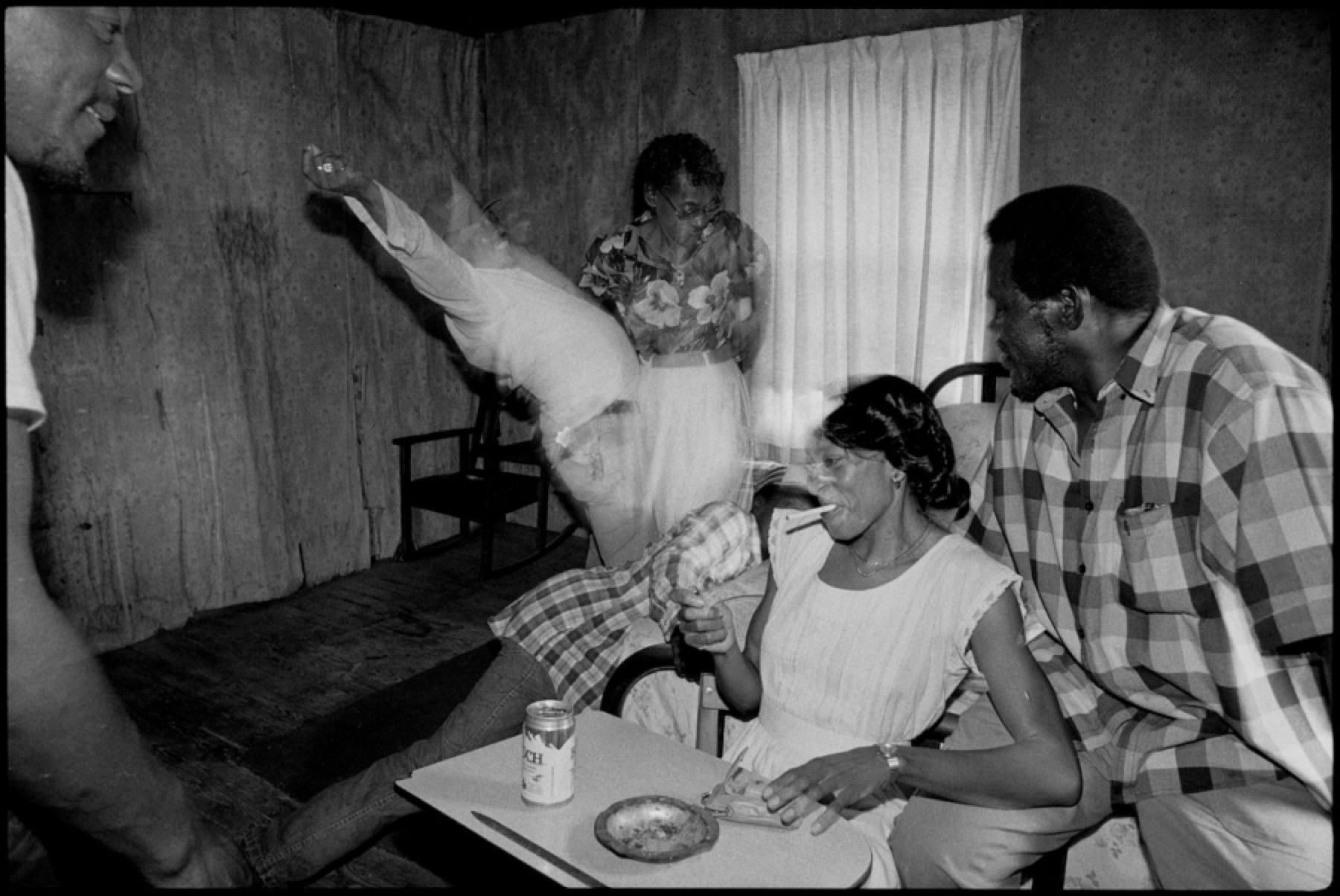

House party at Junior Kimbrough’s in Holly Springs, Mississippi (1988). Photo by David Katzenstein

Play Me Down Home

By Rashod Ollison

Ma Rene, my great-grandmother on Mama’s side, was a no-nonsense blueswoman. Wide-hipped, bowlegged, and solidly built, she stood barely five feet tall and had a wicked tongue. Her barbecue ribs—and the secret sauce she slow-simmered to go with them—made you want to hurt somebody.

She lived in Malvern, Arkansas, on a narrow road with one dimly lit streetlamp the night seemed to swallow. Turn out the lights in her house to go to bed, and you couldn’t see your hand before your face. Friday and Saturday nights, however, the lights didn’t go out until the early morning hours, not until neighbors and friends had stepped back out on the porch and gingerly managed the stairs that led into the front yard, not until every soul had staggered back home in the dark.

Ma Rene’s place was the good-time joint “’Cross Creek,” where the funky black folks lived and worked. She welcomed all walks of life, from whores and Holy Rollers to vagrants and knucklehead kids. Growing up forty-five minutes away in Hot Springs, I loved visiting Ma Rene’s raucous home in the summertime, where the air sat thick with the scents of stale beer, cigarette smoke, Pine-Sol, and pungent cooking seasonings. Malvern was something of a destination city, near the middle of the state, where a flood of blacks moved in the early 1900s. Jobs were plentiful at the Acme Brick Company and Reynolds aluminum plant. By the fifties, a relatively comfortable black middle class was established in Malvern. Away from work and church, the sons and daughters of sharecroppers from desperately poor towns in southern and eastern Arkansas, and as far away as the Mississippi Delta, lived and played hard. Those characters who passed in and out of Ma Rene’s front door terrified and thrilled me.

Some had the saddest eyes I’ve ever known. Chrissy Pooh, a regular at Ma Rene’s, routinely bumbled down the streets drunk off her ass, shouting back at barking dogs and screaming up at maples and sycamores. Or Miss Bernice, with her frail self—a woman who had been a beauty in her younger days but whose regular swigs from the whiskey bottle had ravaged her looks and made her mean. (Years later, just before she died, she stopped drinking, fattened up, and gave her life to Christ.)

These people enjoyed the barbecue, fried pork skins, and brown liquor that Ma Rene sold out of her kitchen, not to mention the camaraderie they got for free. But the music was the strongest draw. In the rear of her home, in a spacious room that might have been another bedroom or a den, Ma Rene kept an impressive Seeburg jukebox. A cigarette machine stood against one wall, and a long couch sat across the room opposite the Seeburg. Many evenings, my six-year-old face pressed against the glass as the mechanical arm placed a 45 on the tiny turntable just before the needle dropped into the first groove. I noticed that the records selected by Ma Rene’s visitors usually had the same label—an impressionistic watercolor of two trees with interlocking branches, the name malaco in blocky black and white letters across the top.

Malaco, headquartered about 260 miles down the highway in Jackson, Mississippi, is an independent label whose recordings in the 1980s spoke directly to the hard-knock lives of my working-class folks who lived in Central Arkansas and the Delta. The music even reached Chicago, Detroit, St. Louis, and Cleveland—“upper country,” where Southern migrants had long settled but held on to their earthy ways.

The blues Malaco released was not the rustic kind celebrated by white city-slick enthusiasts who believed the most authentic sounds bloomed in myth, misery, and pain. It was not the amiable blues thickly coated with pop gloss that garnered Grammys, platinum plaques, and a far-reaching, mostly white fan base for Robert Cray. Malaco blues in the 1980s was not without its polish, but it didn’t mean a thing without that funky grit. The voices shocking those songs to life—seasoned, rough, and ragged—had been steeped in the revolutionary gospel of the 1950s.

The biggest names on Malaco’s roster during the Reagan era included Z. Z. Hill, Bobby “Blue” Bland, Johnnie Taylor, Denise LaSalle, Little Milton, and Latimore—refugees of the golden age of Southern soul. (Bland had also been a huge r&b star back in the late fifties and early sixties.) But by the time they all signed with Malaco, they were veterans—still vital but not relevant to the synthesizer-driven urban-pop and nascent hip-hop overtaking airwaves. Not incidentally, they were also middle-aged, hardly ideal for the youth-obsessed music-video culture suddenly propelling the industry.

Besides, they had become stars at a time when more emphasis was placed on a unique talent and engaging stage presence. At Malaco, these still mattered. The blues that came out of Jackson was a throwback with just the right amount of contemporary touches—stripped down to the genre’s funky essence but brightened enough with production elements to keep the music from sounding like a museum artifact.

Lyrically, the songs were catchy and often unabashedly raunchy—an inherent part of what makes the blues such delicious grown-up music. The Malaco records that played on the Seeburg at Ma Rene’s didn’t wallow in self-pity or perpetuate caricatures of poor blacks. If anything, those records celebrated an indomitable spirit, encouraging listeners to laugh, not cry; to rise in love, not fall. (Or: to leave that no-good muthafucka who’s been “cheating in the next room.”) Malaco blues carried a hip vibe while extending a very old ethos of black music, the blues in particular, as a healing force.

Malaco traces its roots back to 1961, when a pair of white soul enthusiasts named Tommy Couch and Wolf Stephenson began booking bands for their Ole Miss fraternity. At the time, Ma Rene operated a café attached to her home. Back then, she was married to Daddy Jack, who worked for a railroad company and from whom Ma Rene learned the art of barbecuing. I never knew him; he’d quit Ma Rene and split long before I was born. The café died, too, soon after he took up with another woman.

But back when the joint was jumping, when my mother and her siblings were grade school age, the jukebox spun the early r&b that Malaco later revived and extended. Louis Jordan, Ruth Brown, LaVern Baker, Ray Charles, B. B. King, Bobby “Blue” Bland, Big Joe Turner, Big Maybelle—the blues informed the emergent r&b they sang and charged the concurrent rock & roll movement. Rhythm & blues morphed into soul by the mid-sixties, and Southern studios in Memphis and Muscle Shoals became hotbeds for landmark recordings by Otis Redding, Wilson Pickett, Percy Sledge, and Aretha Franklin.

But as the seventies dawned, soul and other forms of black art in the mainstream shifted to reflect the angst of broken promises post–civil rights. The tension behind the unrelenting drive for more sociopolitical inclusion also pulsed through the lyrics and music. The expanding consciousness of black folks—symbolized by globular Afros—colored the urbane hits pumping out of Motown (itself a pop revolution) and Philadelphia International. By mid-decade, black bands such as Earth, Wind & Fire ascended to superstardom, topping the pop charts with inspirational funk like “Shining Star.” The pool of influences in soul had extended well beyond gospel and the blues, sounds born and nurtured in the South. Classical, Afro-Cuban, experimental jazz, reggae, rock—they all were braided into the ever-changing “black music” of the 1970s. And then there was disco, which cleaned out any grit still left in soul.

Traces of the South—a destination for so many pop stars barely a decade before—now seemed all but invisible in the black mainstream. Then in 1976, Malaco, which had been off course for a while and on the brink of closing, struck international gold with Dorothy Moore’s “Misty Blue,” an aching country-soul ballad awash with strings and warmed by Moore’s gospel-blues vocals. The record was a favorite of Chrissy Pooh’s when she visited Ma Rene’s place. My aunt told me that Chrissy Pooh would select the tune on the Seeburg and, pitifully drunk, slow dance with her shadow on the wall.

By the time I was in kindergarten, I was baptized in the blues. The music dominated our house, along with the baby boomer soul of my parents’ generation. These days also delivered the monumental release of Michael Jackson’s Thriller, which ruled the charts for two years, became the biggest-selling album of all time, and rocked my Hot Springs world. But the grown folks around the way, especially those over forty, paid very little attention to the inescapable music by the former Motown prince. A new Malaco album, Down Home, by the Texan Z. Z. Hill, took off that spring as the Thriller for blues people.

Songs from that album, particularly “Down Home Blues” and “Cheating in the Next Room,” were ubiquitous on local radio and at Ma Rene’s. “Down Home Blues” was her anthem. She’d lift herself from her seat and roll her ample ass to the song’s slinky bass line. The LP blared on the console stereo in the living room, and Hill 45s were a mainstay on the Seeburg in the back room. As more and more of the blues drained from r&b, the success of Down Home came like a funky wind from nowhere.

A soul journeyman adrift for years, Hill had at last found a sympathetic recording home at Malaco. His productions eschewed the trends of the day—no synthesizers and absolutely no concessions to electro-funk or early hip-hop. Strutting horns and a tight rhythm section with punchy piano chords and churchy organ lines backed Hill’s intense, attractively frayed vocals. He sang of the messiness of love—its deceit, lust, ecstasy, and devotion—in a whiskey-soaked growl largely absent from the black music charts in the early eighties, where the soaring, clear tones of Rick James, Teena Marie, and Evelyn “Champagne” King owned Jet magazine’s Top 10 every week. Malaco’s flagship artist, Hill stubbornly reminded us that, despite the devastation of Reaganomics and the havoc of AIDS and crack, black communities could still find stabilizing warmth in the blues. Working-class black folks craved such sounds; Malaco gave them what they needed.

Down Home went gold, selling in excess of 500,000 copies, unprecedented for an unabashed blues record on an indie label at that time. It stayed on the Billboard r&b charts for nearly two years. With his switchblade-sharp three-piece suits, thick mustache, and bedroom eyes, Hill became a blues sex symbol and sold out clubs and medium-sized venues around the country. Subsequent albums—The Rhythm and the Blues, released in late 1982, and I’m a Blues Man, out the next year—continued Hill’s hot streak. Singles such as “Someone Else Is Steppin’ In,” written by gifted Malaco artist Denise LaSalle, always got the party started at Ma Rene’s.

Then at the height of Hill’s stardom, which he achieved after toiling for nearly twenty years on various labels with limited success, he died on April 27, 1984: complications from a blood clot. He was forty-eight. It was a crippling blow to the blues world. Its hero, the unassuming man who had brought the blues back to national chart prominence, was suddenly gone. Around the same time, Ma Rene discovered a knot in her breast. Not sure what it was, she had tried to heal it with homemade salves concocted from herbs and menthol rub. Of course, it was worse than she thought.

My last memory of her is that sunny, late spring day she went into the hospital: my uncles Henry and Wayne, busy loading her suitcases into Henry’s truck, Ma Rene on her porch, dressed to impress in a clover-green pantsuit and a bouffant wig, her lipstick red as a cardinal’s wing. I was seven years old. Nobody ever explained anything to kids. I looked up at Ma Rene’s face, a stern mask as she stared straight ahead at the woods in front of her house. No fear revealed itself in her eyes, just a look that said she would stand right there and not be moved. But Uncle Henry said, “C’mon. Time to go.” And she slowly made her way down the steps and into his truck. She’d never return home.

Elrene Simon died on August 11, 1984. She was seventy-two. Mama decided that my sister Reagan and I were too young to attend the funeral, so we stayed behind with cousins. On the day they buried her, I remember walking past her place alone. That rambling house, a character itself, was locked and silent; a chill came on me. It was a sweltering day.

Ma Rene’s house is no longer there; ’Cross Creek in Malvern is gone. Mama Teacake, my grandmother and Ma Rene’s only child, had the place razed about a decade after her mother died. Weeds overtook the lot. Nearly all the folks who frequented her place, the people who ate Ma Rene’s tender barbecue and drank limitless cans of Budweiser, who laughed out loud and boogied to the blues in the back room, are dead. Mama Teacake’s gone, too. But Malaco lived on, never abandoning its core product—the unadorned blues and gospel reflective of its loyal, mostly working-class, black Southern base. Still, the label’s golden era—1975 to 1985—will never be replicated.

I’m more than thirty years removed from that shy kid who stood in a corner at Ma Rene’s, wide-eyed at all the grown-folk fun. My generation was shaped by the childlike magic of Michael Jackson and the navel-gazing angst of grunge and hip-hop, foreign characteristics to the unvarnished, openhearted music of my elders. Every now and then, I’ll pull from the shelf one of those albums by Z. Z. Hill or Denise LaSalle. To the lines that once flew over my head, I now nod and say, “Amen.” I’ve done my share of loving and living. The Malaco blues seemed to know I’d get there someday.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.