The Soft Things

By Holly Haworth

If you are the type whose eyes get caught on beautiful things, you might find, should you be lucky enough to see inside a freshwater mussel, that your gaze will linger on the smooth, nacreous basins of its upturned shell. Last summer, at the Paul W. Parmalee Malacological Collection that’s housed in the McClung Museum of Natural History & Culture at the University of Tennessee, my eyes landed in the two basins of a bivalve’s shell and I could not quit looking: an iridescent porcelain with a nebula of pink at the curved edges as if opening into another dimension. And then there was the periostracum, the outside of the shell: satiny gold-green and streaked irregularly with rays the color of algae. This was the shell of an Epioblasma brevidens, the endangered Cumberlandian combshell.

Cumberlandian is also the name of the region comprising the Tennessee and Cumberland river watersheds that biologists have recognized as containing the richest freshwater mussel fauna in the world. Floating placidly on a pontoon atop the Fort Loudoun Lake impoundment, almost within sight of the museum in Knoxville, you can point a finger straight down into the opaque depths where once, some eighty feet below, there stretched a broad complex of shoals—banks of cobble, gravel, pebble, and sand with clear water riffling over them. Between the cobble and the gravel and the pebble, mussels buried themselves into the sand by the thousands or tens of thousands, protruding from the riverbed like strange bulbs. Now, more nonliving specimens can be found in the museum than living ones downhill of it in the Tennessee River—a river that you might call a series of deep, silty lakes. The region’s remaining native mussels (ninety-six species) are hanging on, though, tenaciously, in the many tributaries.

The Epioblasma genus has lost seventeen species in Tennessee—species that thrived in big rivers with shallow habitats like what the Tennessee River once provided, before it was impounded by dams. “Those mussels that were endemic to the Tennessee River proper are all pretty much gone, and they aren’t coming back,” Gerry Dinkins, the collection’s curator, said to me. It is not just dams that have hurt mussel populations. You know this story: habitat loss, agricultural runoff, erosion due to development, silt, pollution from sewage, coal mining, oil and gas drilling. Overall, 70 percent of Tennessee’s mussel species have gone extinct or suffered a significant decline in the last century.

For days in a row I returned to visit the cool museum basement, where thousands of specimens like the Epioblasma brevidens are housed—more than a hundred thousand of them. Gerry’s assistant, a graduate student named Kristin Irwin, had spent the summer cataloguing: numbering them and entering them into a database, with information about where and when each specimen was collected. Many were from the personal collection of the late zooarchaeologist Paul Parmalee, whose passion for freshwater mussels was sparked by his excavations of the region’s shell middens—massive heaps of shell that humans piled up on the riverbanks beginning some ten thousand years ago. Mussels were a major food source for indigenous people, who made both temporary camps and permanent settlements next to mussel-rich areas of the river.

“Which ones are you interested in seeing?” Kristin asked me.

“All of them,” I said.

She was happy to entertain my request. As an undergraduate in environmental studies, Kristin had fallen for mussels. For her, it began with the circular lines that appear on the outside of the shells. Mussels, which can live more than one hundred years, have the longest lifespan of all freshwater invertebrates, and they form growth rings like trees do that help biologists to determine their age. Kristin is the only student in her graduate program pursuing the mysteries of these little-known bivalves. In the sciences, they are not among the most charismatic creatures. And yet to some, they captivate.

Kristin handed me the two halves of a Tennessee pigtoe, also endemic to the Cumberlandian region, currently petitioned to be listed as endangered. “Pleuronia barnesiana,” she said. “I love this one.”

I took it in my hands. It was labeled in a neat yet shaky script: “Duck River, Hooper Island, Maury Co., TN. 7/21/77.” A small, round, thick shell, the outside smooth and brown, with dark concentric ridges—the growth rings. I turned it under the hanging fluorescents. Its nacre—the interior layer—was the white of a winter sky, distant light gathering behind thick cumulus.

Mussels are of the Mollusca phylum, which also includes squid and octopuses; the Latin word molluscus was adapted from a Greek phrase meaning “the soft things.” As they evolved, during the Cambrian Period, around five hundred and forty million years ago, some mollusks began to enclose their soft bodies in shells of calcium carbonate that could be hinged open. These became the Bivalvia class (the Latin bi- meaning “two” and valvae meaning “leaves of a door”), which includes clams and oysters, filter feeders that latched on to rock or buried themselves in sediment and crawled slowly along the ocean floor. Freshwater bivalves evolved by sending their larvae up rivers in the gills of spawning salmon. Now, like their ocean ancestors, they live out some of the most obscure lives on the planet, clasped in a darkness of their own creation, sometimes for up to a century or more. “Under a firmament of nacre,” wrote the French poet Francis Ponge about the oyster. A firmament, yes, because, like the sky, it is vast and ancient. Because, like the sky, you can get lost in it.

I placed the valves back together and they met with a satisfying clank, like a locket. While I was lost in the pigtoe, Kristin had slid open another of the metal drawers in which the specimens were stored and selected the next for me. “Villosa vanuxemensis,” she said, gently placing it in my palm.

We went on like this. There was the heavy, bumpy shell of Cyclonaias tuberculata, the purple wartyback, with a nacre the color of blueberry bubblegum. And the oblong Cumberlandia monodonta, the spectaclecase. True to its name, it could have held within it a pair of reading glasses. There was Epioblasma triquetra, the snuffbox, which would have been, yes, the perfect place to keep a pinch of snuff. And the tiny southern acornshell, several of which would have fit into a squirrel’s cheek.

There was the fat floater, the narrow catspaw, the sugarspoon, the golden riffleshell. The rabbitsfoot, the cracking pearlymussel, the tubercled blossom, the finelined pocketbook, and the Tennessee heelsplitter. The giant washboard, the orangefoot pimpleback, the sheepnose, the pink mucket, the fragile papershell, and the Appalachian monkeyface. The pistolgrip, the fawnsfoot, the pale lilliput. The pondhorn, the bankclimber, and the rayed bean. And that was only the beginning.

I held shells of all sizes, colors, textures, thicknesses, weights, and shapes. As she passed each to me, Kristin told me what she liked about it, pointed out the features that made it unique. “Truncilla truncata,” she said, handing me one. “This is my favorite. The deer toe. See the chevron patterns on the periostracum?” Angled lines on the shell resembled the prints of the hooves of a deer, walking a path across it. Its color was spruce with bands of mossy-yellow.

“This isn’t the animal,” Kristin reminded me. “This is only the animal’s secretion.”

To see the animal, I went to the Clinch River, at Kyles Ford, in the far northeast corner of the state, where many of the museum’s specimens had been collected. Nearly a dozen state and federal wildlife agents had gathered there in September in an effort to revive native mussel populations. Biologists had been sent from the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and even the Appalachian region’s Office of Surface Mining, which employs only two (together responsible for monitoring the effects of mining on aquatic species from the border of Canada in Michigan to the coast of Alabama). Because Kyles Ford has so many diverse species, as well as high numbers of individual mussels, the Mollusk Recovery Program aimed to harvest mussels here and move them into other rivers in the hope that healthy populations can be reestablished throughout the region.

When I arrived in the late afternoon, a shirtless wildlife agent was hanging a wetsuit to dry on the open door of his truck. He lit a cigar and puffed it, releasing a cloud of smoke. I walked over and introduced myself, and he led me through a field of tall weeds, the smell of cigar and goldenrod and river wafting up to me. We came to the bank of a narrow channel that was separated from the main body of the river by a small sandbar. Several agents in wetsuits were hauling in their harvests in heavy mesh bags, while some were still face-down, snorkels sticking up from the shallow currents. Harvesting selectively—to ensure that a sufficient number of both females and males are collected from a checklist of species—requires a close-up view of the riverbed. Snorkeling agents plucked mussels from the substrate like turnips from loose soil, filled their bags with them.

I met Don Hubbs, coordinator of the Mollusk Recovery Program, onshore. He wore a khaki shirt with a TWRA patch on the breast and a fisherman’s hat and sat with his feet in the channel and a clipboard on his lap. Next to him, a wide, flat rock served as a field table. In front of it, an agent sat on a bucket turned upside down in the stream. He lifted a red mesh bag from where it had lain submerged along with many others and emptied it out in a pile, the shells clattering onto the rock, a molluscan ruckus. Unlike the ones in the museum, all of these shells were closed, held tightly shut by the creatures’ adductor muscles. (Kristin had told me that the living ones are “almost humanly impossible to pry open.”)

“Epioblasma capsaeformis,” the agent on the bucket said, and Don made a mark on his clipboard. The two agents began to count, taking mussels from the large pile and making smaller piles, saying numbers under their breath, and Don turned to me to speak. “The oystermussel,” he said quietly, just above the clatter and the current.

“Its host fish are fantail or redline darters, and those darters feed on aquatic insects,” he told me. Don sounded like a cowboy telling a lonesome story. “So the female oyster will put out a lure with two little antennae.” He pronounced it anten-ee. He wiggled two fingers around, mimicking the mussel that mimics an aquatic insect. “She’ll just wiggle them little antennae,” he said. “Then a darter will come, and she’ll grab on and pump glochidia into its gills.”

Because mussels are mostly sedentary, they rely on fish to carry their larvae, or glochidia, upstream, just as their long-ago ancestors first used salmon to move from a life in the ocean to a riverine existence. Each species of mussel has developed its own unique lure to bait the species of fish that is able to transport its progeny; larvae are chemically unable to bind to the gills of fish that are not their hosts. The fish, too, have perhaps adapted receptor cells in their gills that will respond only to a certain mussel. No one actually knows the full intricacy of the relationship, for the lives of freshwater mussels remain so little known, little seen. A very small number of scientists have ever studied them.

Still waiting on the count, Don told me of another, the birdwing pearlymussel. “Its host fish is a banded darter, and banded darters feed on snails,” he said. “So the birdwing puts out a lure that looks like a little snail climbing up a rock.” He shaped his left index into a snail and his right fist into a rock, his index crawling up his fist. “When the darter comes up to bite that snail, it gets a cloud of larvae instead. So you have a mollusk imitating a mollusk to trick a vertebrate.”

You might call this adaptation “smart.” But mussels have no brains—no eyes, even. In much the same way that orchids adapted a myriad of shapes, olfactory cocktails, colors, and petal arrangements in order to attract their pollinators, Don told me, mussels have formed a myriad of lure designs to attract their hosts. When a gravid female hinges open the doors of her shell and sends out a lure, it is as if an orchid is blooming under the current.

The count was in. “Four hundred ninety-four,” the agent called out, and Don scribbled it down on his clipboard. I was reminded of the signature line of Don’s email—an E. O. Wilson quote: “The ideal scientist thinks like a poet and only later works like a bookkeeper.” Here, Don was doing both at once.

After returning the oystermussels to their bag in the stream, the agents dumped out the next and began to count pheasantshells. Don, peering into the water, noticed something. He dipped his hand in and brought up a mussel that he laid in my palm. “Dromus dromas,” he said. “The dromedary. Dromedary is a type of camel.” He paused while I felt the distinctive hump on the shell. The mussel is critically endangered, he told me, with the only remaining populations here and in one of the Clinch’s tributaries.

Another wet-suited agent, Steve Ahlstedt, had come in to deliver his harvest. Others had spoken of Steve as “the Tennessee mussel guy.” A retired biologist with the U.S. Geological Survey, Steve keeps involved in conservation efforts. He climbed the bank and stood dripping, gestured toward the sweep of river. “Kyles Ford is the most biologically diverse spot in North America for mussels,” he proclaimed excitedly. He picked up the empty shell of a spectaclecase and examined it.

The agents were piling up pheasantshells, mumbling numbers. “Sun’s gone down,” Don mused. There was much counting left to do. Tomorrow I would join Steve and a team of several others at another river fifty miles south, where we would seed the riverbed with these mussels.

From where it begins in western North Carolina, the Nolichucky River drains some of the most rugged country in the East, cuts narrowly through the Unaka Mountains, and snakes out in long meanders, before it finally joins the French Broad, a tributary of the Tennessee. To look at a map of the region is to see a land stitched with fine threads of blue—thousands, there is no counting them all. These reaches of southern Appalachia were never touched by the glaciers that spread intermittently across the northern parts of the mountains over the past two million years. While waterways to the north were locked in ice, these kept flowing, and life here continued to evolve and adapt into great intricacy. Many species are endemic, occurring in only one or two streams. That makes this diversity not only astounding but also tenuous. The Nolichucky historically hosted an estimated forty species of mussels; now it is home to twenty-nine.

Steve threw me a wetsuit. The sun was full and high above Evans Island, hot for September, but the water after several hours might bring on a chill. A handful of male agents were suiting up behind the open doors of the two trucks we had driven. In the beds of the trucks were fifty-gallon coolers that we had packed full of mussels that morning, carrying the mesh bags up from the narrow channel at Kyles Ford, where they had spent the night submerged. Behind a wooden privy I squeezed myself into the black neoprene suit.

We lugged the bags to the bank, steep and high with grasses, where we descended a metal ladder to the pebbly shore. We forded the river through a current that tugged at the knees, to a small island. Steve pointed each of us in a direction. “Find a sandy spot and wedge them down into the substrate,” he said. He bent down and demonstrated with one, pushing it into the soft sand. “That’s it.” We dispersed.

Underwater, through my snorkeling mask, the world became more vivid. The water shimmered with miniscule specks of mica that floated and drifted like dust, illuminated in the wide beams of sun that fell through the surface. The mica still washes down from old mines upstream. Snails clung to the rocks. A minnow the size of my pinky finger, with steady, alert eyes, plied the current.

I placed my palms against the riverbed and let my legs float out behind me as I took Elliptio dilatata, or spikes, one by one from my mesh bag and pushed them into the substrate. I saw that some mussels had their feeding apertures open, a lattice of comblike gills through which they filtered suspended organic material such as phytoplankton, zooplankton, algae, diatoms, bacteria, and detritus, each individual processing up to fifty gallons of the water column a day, so that a whole population of mussels works as a natural filtering system at the bottom of the river. I watched as one aperture sucked things in as the hose of a vacuum sucks in dirt, and another aperture shot out tiny pellets of waste that macro-invertebrates such as mayflies, stoneflies, and caddis flies would then eat.

Once or twice I lifted my head above the surface to see the black wetsuits floating upstream, the snorkels sticking out. Each time I did this, I was eager to put my head back under the water, to reenter that other world. My ears submerged, I heard only the muted scrape of sand scouring the bottoms of the rocks that I put the weight of my hands and arms against. All else was silent.

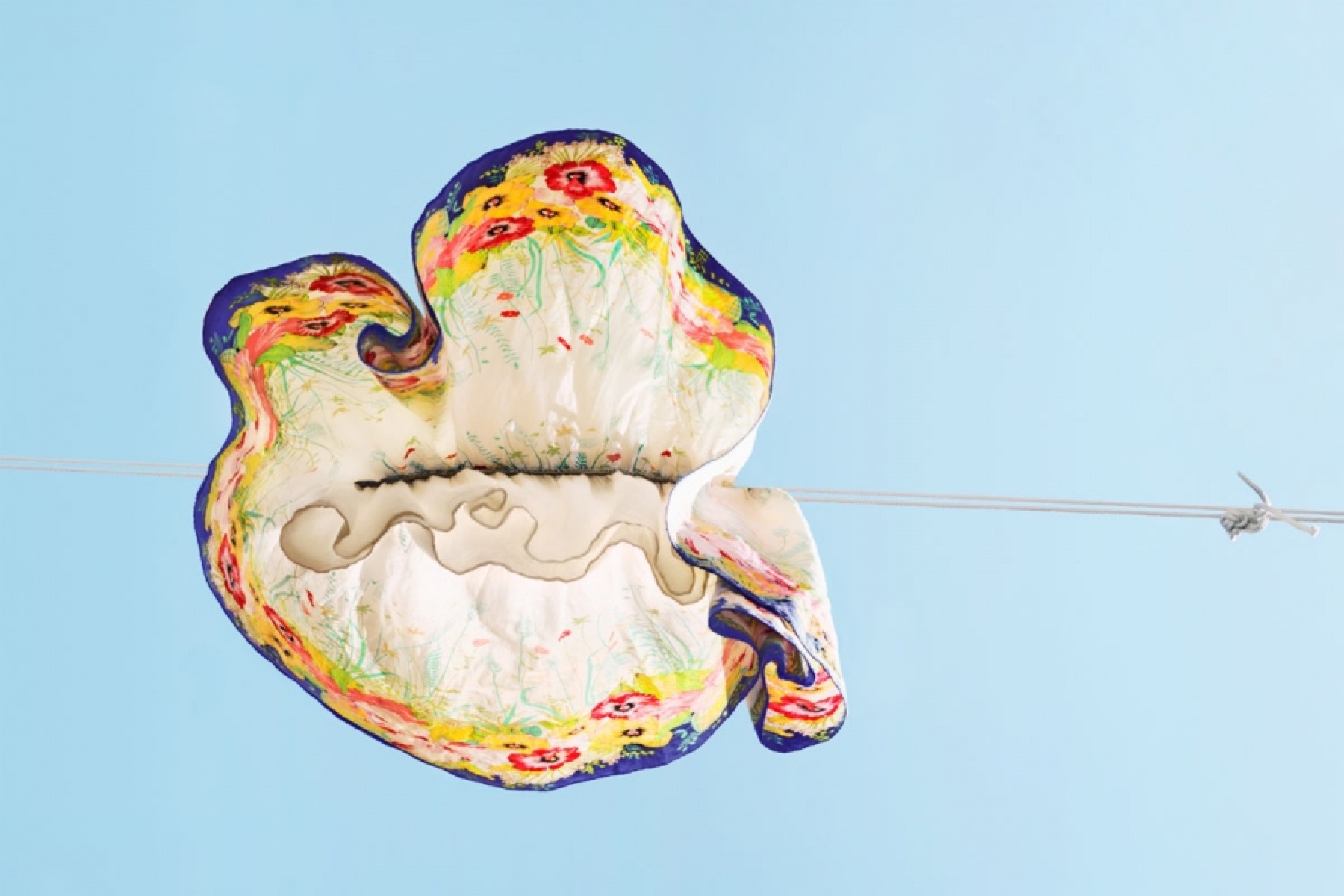

Among large, smooth stones and smaller, more jagged pieces of rock, a pocketbook mussel had cracked open the doors of her shell. Between the two valves there stretched a matrix of soft tissue; the mussel, a female, had extended what’s called a mantle, a thick, creamy protrusion of flesh with gray mottling. At the top of the mantle, two flaps came together to form the shape of a minnow, complete with an eyelike dot on each side. It looked nearly identical to the minnow I had seen moments before.

Holding on to a rock, I pulled myself closer until I floated facedown just above it. The tail and fins of the imitation minnow billowed along every frilled edge. I could see the mussel contracting her mantle at regular intervals with subtle pulses, which caused the “minnow” to shimmy its body side to side.

Bass eat the minnows that the pocketbook mussel mimics. I waited and watched, hoping that at any moment a bass might come and grab the bait so that I could witness the mussel snapping closed the halves of her shell on the bass’s mouth, the bass trying to wriggle away, the mussel grasping it within her strongly clenched shell as she pumped a spray of larvae from her marsupium pouch into the gills of the bass—and then the release, the bass propelling away from her, the mussel relaxing.

A rock shifted under the grip of my hand. In a quick movement, the mussel withdrew the flaps of her mantle, pulled the lure in, and sealed herself closed. It looked then like nothing more than a brown rock.

I turned back to the spikes, pushing each down into the sand, leaving only the tops exposed, where they would later open to feed, or, if gravid, to display lures. I worked my way across the width of the river that Steve had assigned to me, spacing the mussels out in rows as if planting a crop, pulling the mesh bag through the water. We planted some fifteen species that day in different patches of the river, several hundred of each, every one of them pushed into the substrate by a hand. Each hand had been attached to a human who hoped to restore a piece of the world that could easily be forgotten.

When a mussel dies in its shell, its adductor muscles no longer hold the valves tightly closed. The shell, once almost humanly impossible to pry apart, hinges open, and a puddle of flesh lies inert inside. The Mollusk Recovery Program biologists had noticed many shells like this that day at Kyles Ford in September. They spoke quietly about it and did not tell me, Steve said later, because they were not yet sure—but they suspected a problem.

In October, I was shocked when Steve wrote to me to say that a widespread die-off was underway in the Clinch, for a stretch of thirty miles, upstream and downstream of Kyles Ford, where the mussels had been gathered only weeks before. When they went back to investigate, he explained, they found the open shells of mussels scattered all along the shoals. Steve picked up shells and turned them over; black Jell-O plopped out of them.

They did not know the cause. There were many factors to look at: herbicides being sprayed under nearby power lines, coal mining upstream in Virginia, oil and gas drilling, contaminated sediments, illegal dumping from bridges. Those shells, the animal’s secretion—an adaptation meant to enclose the soft things and protect them from harm—cannot protect them from the secretions of human industry that ooze and seep past all barriers. Steve picked up thousands of shells of freshly dead mussels, and he left thousands more there. The thousands that he gathered he took to the McClung Museum, where they will be cleaned, catalogued, and curated into the collection.

I go to the shelf where I have lined up the shells that I collected last summer. I open one and stare into its opalescent basin. The nacre inside is seen only when the animal dies. Why this beauty? Kristin and I had wondered at the museum. The spectrum of colors in that milky sheen cannot be seen by predators, or by the eyeless animal that creates it. At death, light spills in and reveals the animal’s creation. I think of all that secret shining tucked away in riverbeds, inside the drab, brownish, stonelike exteriors.

I clank the shell back together. It fits inside my palm. This isn’t the animal. Just proof—beautiful, hard proof—that it once existed.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.