Speed Away

By Jamie Quatro

This, too, is holy

Soaring above everything, the spires. Sanctus, sanctus, they cry. They are hollow. The cathedral was never completed, its doors lead both ways into open air. Malcolm has walked, in the calm Barcelona evening, around this empty monument many times. He has stuffed peseta notes, virtually worthless, into the slot marked: DONATIONS TO CONTINUE THE WORK. It seems on the other side they are simply falling to the ground or, he listens closely, a priest wearing glasses locks them in a wooden box.

The passage above is from James Salter’s “Am Strande von Tanger,” published in the Paris Review in 1968 and later collected in Dusk and Other Stories. The Barcelona cathedral is, of course, the Sagrada Família, a wildly ornate (and still unfinished) Roman Catholic basilica designed by Catalan Modernista architect Antoni Gaudí. Construction began in 1882, but Gaudí knew it wouldn’t be completed in his lifetime. “My client is not in a hurry,” he is reputed to have said. The structure is a surrealist fever dream reminiscent of religious outsider art, a visual representation of the kind of obsessive faith that feels at once prophetic and insane.

The Sagrada Família isn’t central to Salter’s plot—the image is working tonally, and to establish character, as Malcolm sees in himself “evidence of a process not fully complete. . . . [H]e is preparing for the arrival of that great artist he one day expects to be”—but the description of the empty cathedral is what’s stuck with me since I first read the story in graduate school. I feel a gut-drop sense of grief each time I reread it. The hollow spires, the doors leading “both ways” into open air, the hypothetical priest “wearing glasses” (note Salter’s subtle chide in using this detail: the imagined glasses give us the priest’s failing eyes and the narrator’s vanity, as we’ve just learned a few paragraphs earlier that Malcolm himself sports a pair of glasses with no prescription lenses in them), the wooden box clicking shut: images of emptiness, futility, disappearance, and loss. As if the vacant cathedral is a mute proclamation of the vacuity of faith itself.

But God is everywhere, a theologian might remind me. The “church” is a metonymy: an invisible building made entirely of redeemed souls.

Still, each time I see another tiny church with a FOR SALE sign, or a stone chapel turned into condominiums, or a historic cathedral used as an event space for wedding receptions and art openings, I feel similarly bereft. Especially here in Chattanooga, in what is increasingly becoming (if it isn’t already) the post-Christian South. For years I’ve been photographing these former houses of worship, lurking, researching their passionate beginnings, early flourishings, eventual founderings, and final closures.

Why all my wet-rag nostalgia attached to brick and stone and mortar? Shouldn’t the shuttering churches be a cause for celebration—a sign that finally, finally we’re enlightened enough to do away with them?

Tell me your obsessions as an adult, and I’ll tell you what you were deprived of as a child.

I was raised in the Church of Christ, a stripped-down “anti” denomination that grew out of the American Restoration movement. The traditional councils and denominational hierarchies established in the first century were considered a departure from the purity of the early church; modes of worship not mentioned in the New Testament were deemed inauthentic. Since musical instruments aren’t explicitly mentioned, we sang hymns a cappella. There were no recitations of creeds, no statements of faith. No stained-glass windows narrating Bible stories or iconography—no pictorial representation whatsoever, not even an empty crucifix on the sanctuary wall. Any attempt to render God’s presence in visual form landed you somewhere on the idolatry spectrum.

Alas, poor human creatures, with our meager five senses through which to learn about ourselves and the world. How stubborn our demand for tactility. The lack of imagery and instruments and traditions and creeds meant I was supposed to know and love an abstraction: a God I had to make up in my head. And the Church of Christ’s firmly anti-Calvinist teaching on soteriology held that access to heaven hinged on your adult, informed decision to be baptized by full immersion (the way I understood it, it was a choice you made in a soupy mix of grace and faith). I grew up fearing I could do something that would tip the mercy/justice balance, that the next sin would outweigh whatever mercy I’d stored up—and I’d be like a dog returning to its vomit, shut out from eternity. My rudimentary understanding—though I couldn’t have put this into words as a child—was that I was saved by work, and sanctified by more work.

No wonder I longed for a truth from outside myself, some ultimate, here-and-now reality to which I could simply surrender. Priests and creeds, ritual and liturgy, statues and icons and religious paintings: all held the dual allure of being tactile and forbidden. The house I grew up in was next door to an Episcopal church. I would sneak into the chapel just to see the low-burning candles and stained glass and suffering near-naked Christ drooping from the crucifix above the altar. At night I would blissfully terrify myself by turning to a Michael Pacher painting in my mother’s art history book, a depiction of Satan standing in a kind of face-off with a man who looked, to me, like the Pope. It turned out Satan was a green lizard with emaciated limbs and bat wings and red eyes in his butt. My Scots-Irish uncle in California married a woman from Portugal, so my cousins grew up Catholic. How I envied their rosaries and medals and little prayer books with picture-cards of saints tucked inside. And the priests, tangible spiritual fathers who could administer tangible blessings: a touch on the head, the placement of a wafer on the tongue. The swaying incense, the font of holy water, the kneeling and rising, and best of all the confessional, a little closet with the sliding window in which Catholics could sit and say, “Bless me, Father, for I have sinned.”

I was too young, too Protestant, to understand the Incarnation as evidence that God not only sanctions but delights in embodiment. That we were made to experience him through the hard-edged, thrilling reality of skin and bone, scent and touch, color and paint and glass.

The division among denominations, the violence of church history, the injustices and oppression of women and minorities, the absolutely impossible-to-keep rules—why not join the rest of the enlightened world and give it up? I wish I could. It’s not for lack of trying. Maybe I’m brainwashed, maybe I’m too tied to my upbringing to escape the religious impulse, but after all the arguing and intellectualizing, there is something left in me that cries out, like Salter’s abortive spires, sanctus. This despite the darkness of doubt in which I often find myself groping around for some familiar object to help me navigate (but “[F]aith is not necessarily, or not soon, a resting place,” Wendell Berry says. “Faith puts you out on a wide river in a boat, in the fog, in the dark.”) This despite the current political climate, in which right-wing “evangelicals” (how that lovely 1530s word has become tainted) seem to have permanently defamed and undermined the term “Christian” and all it’s supposed to mean: welcoming foreigners and aliens, caring for the poor, fighting injustice. How terrifying to confess, aloud, that one is still in the game. “The human creature’s religious instinct is as obdurate and resourceful as its sexual instinct,” John Updike wrote in a 1999 New Yorker essay, “and as impervious to reason. . . . [M]uch of religious loyalty is, after all, a mode of defiance, insisting, This is what I am.”

Well, then, this is what I am: adopted Southerner; no longer a part of the church in which I was raised, but still Protestant, albeit an increasingly reluctant one; saddened by what the “church” has become, both the right-wing fundamentalist variety and the watered-down, meaningless palaver that will have nothing to do with Christ or orthodoxy or even the Bible itself; grieving the shuttering of historic places of worship and hoping to document their histories before they become lost.

Wondering if anything of God is still left hanging around their borders.

Photograph by Maude Schuyler Clay

Photograph by Maude Schuyler Clay

1

Mystic

Patten Memorial African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church

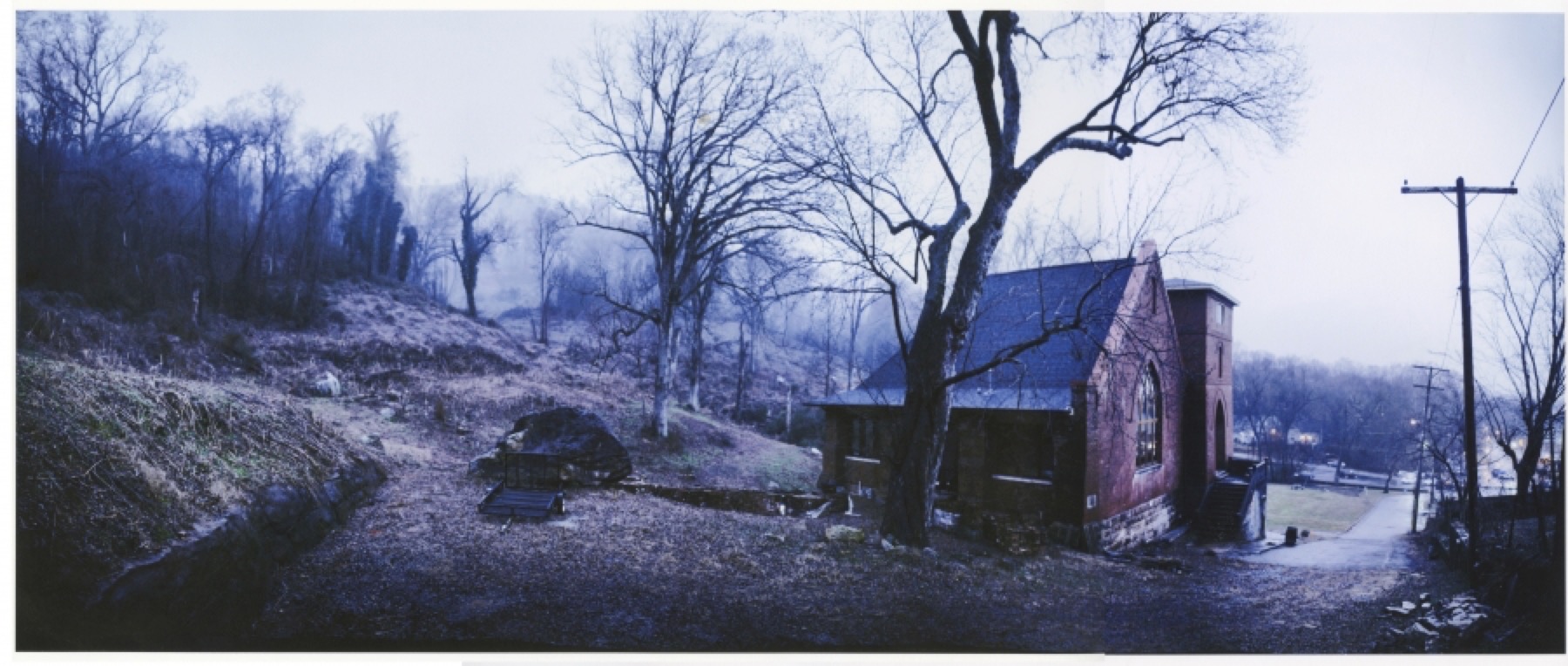

At the corner of 38th and Church Streets in St. Elmo, Tennessee—at the foot of Lookout Mountain, where I live—sits a compact brick church with large gothic windows. The building is nestled into the hillside behind the Chattem Drug and Chemical Company. It has been abandoned for years, surrounded by a field beneath the kudzu-engulfed hillside. In the mornings, when I run on the Guild Trail above St. Elmo, I look down at the roof of the church. Often pockets of fog are trapped between the hillside and giant boulders and trees.

The AME Zion Church was founded in New York City, an outgrowth of the Methodist Episcopal Church. According to a program from Patten Memorial’s 109th anniversary celebration, the new denomination was “necessitated because of discrimination and denial of religious liberty.” The founders determined that the church would “dedicate itself to the liberation of the human spirit.” Often called the “Freedom Church,” it had as some of its earliest members Harriet Tubman, James Varick, Frederick Douglass, and Sojourner Truth. The church is called African, because it is “led by the sons and daughters of Africa”; Methodist, for its orderly Wesleyan principles; Episcopal, because it is supervised by bishops elected by the general church; and Zion, in reference to the hill of Jerusalem on which the city of David was built. The prophetic passion of its early leaders is evident in this 1895 history written by Bishop J. W. Hood:

But the promise is that princes shall come out of Egypt, and that Ethiopia shall soon stretch forth her hands unto God. . . . That this prophecy is now in the course of fulfillment the Negro Church stands forth as unquestionable evidence. It is the streak of morning light which betokens the coming day. It is the morning star which precedes the rising sun. It is the harbinger of the rising glory of the sons of Ham. It is the first fruit of the countless millions of that race who shall be found in the army with banners in the millennial glory of the Christian Church.

Patten Memorial—the Mystic church—is the oldest church in St. Elmo, built in 1886 by former slaves on land thought to have been given to the black community by Z. C. Patten, who founded what was then called the Chattanooga Medicine Company. Most of the original members were company employees. By the 1950s the congregation was flourishing, with more than two hundred members. But in 1985, when the building was added to the National Register of Historic Places, the membership had dwindled to a few dozen; by 1990, with the Reverend James Brown presiding (“not the soul singer, but the soul winner!” a newspaper clipping proclaims), only twenty members remained. The church closed its doors soon after and the building lay fallow for years, until a local artist bought it. He planned to use it as a studio, but he found a better space and sold it to the current owner, Jeff, who is now in the process of finishing it as his private residence. (Some homeowners’ names have been changed to protect their privacy.)

I’m a huge Van Morrison fan, Jeff tells me. Jeff is a pilot and competitive hang glider. He and his girlfriend, Melanie, and I are standing behind the church, in what will eventually be their landscaped backyard. Boulders and dormant kudzu surround us; a waist-high stack of bricks will eventually be used to make a patio.

I started calling it the Mystic church because of the song, Jeff says. Then they brought in the roll-off container, and one morning someone had tagged it.

He points to the container: SKY.

I figured it was a sign I was supposed to be here, he says. You know, “fly into the mystic.”

Jeff shows me an old sign he’s kept: THE CHURCH ON THE HILL TO DO GOD’S WILL. It seems the church was fond of taglines: In the program from the 109th anniversary celebration, the cover says, Patten Memorial AME Zion Church: “A church where everybody is somebody and Jesus Christ is Lord.”

We don’t want to take you inside yet, he says. It’s a mess.

There’s a red-tailed hawk’s nest in that tree, Melanie tells me. We thought it would be so beautiful to watch him. Now we realize it’s kind of awful. All the squirrels and rabbits and . . . well, it’s bloody.

They tell me their home attracts strange visitors. One night they drove up to see a woman dressed in full goth, with Alice Cooper makeup, posing for pictures in front of their door. Another day a man with a GoPro camera built into a helmet knocked. He asked if he could hike up the hill behind their church. Jeff told him sorry, but it was private property. Ten minutes later they saw him coast past, sitting on a long wooden plank with wheels attached.

It really is a mystical place, Melanie says, the way the fog just sort of hangs out back here in the mornings.

Melanie and I end up hitting it off. We take a long hike together and realize our children have gone to school together for years and are friends. We also discover we were born on the same day, one year apart.

Photograph by Maude Schuyler Clay

Photograph by Maude Schuyler Clay

2

Achain-link fence separates the goods—buckets, doorknobs, slate tiles, pylons—from the sidewalk at this junkyard/perpetual garage sale on Main Street. Otherwise known as “The Original Kewl Art Stuff Store,” it’s owned by a man named Greg Ross. I’ve passed the place dozens, maybe hundreds, of times, always noticing the giant stained-glass window rising from the middle of an ever-changing array of castoffs: Jesus with his arms lifted, perpetually blessing the twice-rejected heaps. As if he’s saying, This, too, is holy.

Today a stop sign is on the ground in front of the stained glass—perhaps today Christ is issuing a command, not a benediction. I stop for the first time in twelve years and find something I’m interested in buying: metal letters soldered together to form conjunctions and prepositions. AND, BUT, ALSO, NEXT, ABOVE, BELOW.

How much? I ask a man named Joe, who is sitting in a folding metal chair.

You got a phone? he asks, cryptically.

I hand him my cell. He dials and hands it back to me. It seems this Joe is the middle man—it’s Greg, wherever he is, who calls the shots on price.

Which words? Greg asks me.

ABOVE and BELOW, I say.

Twenty apiece, Greg says.

Instead I buy a one-dollar Christmas ornament, a ball decoupaged with broken glass and torn bits of calendar. I also buy, for two dollars, a vintage black-and-white photograph with a white scalloped border. The image is of a young boy and girl climbing a stump. Their backs are to the camera, and they remind me of my two youngest children at that age. There’s an elegiac quality to the photo—more elegy in the fact that it’s here, abandoned in a shoebox full of loose photos. Nameless, faceless children someone once loved enough to photograph in this candid moment. I tuck the photograph into the book I’m reading, a copy of a memoir called Love and Trouble.

Photograph by Maude Schuyler Clay

Photograph by Maude Schuyler Clay

3

Joe (of the folding metal chair) tells me the stained-glass Jesus was salvaged from a former church on Williams Street. I know the church he’s talking about—it’s a few blocks away from a tiny studio workspace I rent above an antiques store.

Someone lives there now, Joe tells me. And there’s a swimming pool inside.

The former Alleyne Memorial is a simple rectangular brick building with clear arched windows along each side, where the stained glass used to be. The brick is painted white with brown trim, and the church has a small squared-off belfry. The owner and designer, David, is a well-known restaurateur and chef. He’s gracious enough to let me come inside his home.

The former sanctuary is David’s contemporary-urban living room and kitchen. A standard poodle sprawls on the couch. Electric guitars and sound equipment fill a corner space; in the center of the room, where the aisle between pews would have been, is a statue of Gaia, Mother Earth, with fat babies circling her waist. At the far end of the sanctuary, through a pair of glass doors, is the in-ground swimming pool. It’s small, narrow, surrounded by casual lounge furniture and a gas fire pit. The beams above are open to the sky, each crossbeam covered in tinsel-like spokes.

Before I put in the spokes, I left town and didn’t think about the birds, he says. I had a mess to clean up when I got back. Here, watch this.

He holds what looks like a television remote. He pushes a button and water pours from a fissure near the ceiling into the pool.

A nod to the baptismal? I ask.

I guess, he says. But it’s so loud. That’s the problem with the waterfall—you can’t really have a conversation when it’s on.

David shows me a picture of the old interior and points to the word ETERNITY painted on the back wall behind the altar.

I put in a window where that word used to be, he says. I figured, why have the word when you can have the thing itself?

I look out the window: ETERNITY has been translated into a view of the top half of Lookout Mountain, brilliant sky, a few thin clouds.

The stained-glass windows on either side of the front door—both depictions of Christ—were left in place. The rest of them were headed for the city dump when Greg Ross offered to have them removed intact, David says. You’ve probably seen them over at his place on Main?

The windows, I learn, were made at Statesville Stained Glass in North Carolina. One-inch-thick pieces of colored glass sealed in place with epoxy. The artisans intentionally chipped, or faceted, the glass to create the illusion of depth. The Reverend Cedric Henson was pastor when the windows were purchased for the “bargain” price of $1,500 apiece. Henson left Alleyne in 1998 to help open a new church, Shepherd’s Voice (a name that he says was inspired by one of the stained-glass panels). No one seems to know when, or why, Alleyne Memorial was abandoned.

David and I sit at the table in his kitchen. A tiny green-eyed cat circles my legs, purring. David’s daughter and her friends clomp upstairs from the basement, where the playroom and bedrooms are—the clomping is because they’re wearing Rollerblades. They skate through the kitchen, making circles around Gaia. Downstairs, the television is on. Trump has just announced his first travel ban, and airport protests are spreading throughout the country. We talk about the injustice, the suffering, the despair we feel. At least people are coming together to protest, we say. The two remaining images of Christ rise behind us as we talk, throwing a blaze of color onto the floor. On one side Jesus cradles the recovered lost sheep; on the other, he blesses the children his disciples had tried to banish from his presence. Today, both images feel like accusations.

Photograph by Maude Schuyler Clay

Photograph by Maude Schuyler Clay

4

St. James Methodist Episcopal Church

Most brides are funny about who takes their picture, but this bride, she’s different. I mean, she’s just as sweet as the day is long and if you get here at two you can come on in and look around. You know this church was thriving before they all left for East Ridge in the fifties. White flight, you know. After they all left, this place was a tabernacle. Usher used to come here. He sang in the choir.

Sandi, the woman who handles events at the former St. James Methodist Episcopal Church, gives me this primer over the telephone. (The bride’s sweetness proves true, but Usher actually grew up attending St. Elmo Missionary Baptist Church.) When I arrive, the bride and groom are posing for photographs—it’s postceremony, prereception. When I peek inside the old sanctuary, the guests are waiting at tables, eating hors d’oeuvres. The bride doesn’t seem to mind me there, lurking around, or even notice me at all; she’s awash in a just-married glow. I back out. I don’t want to impose. Anyway, I’ve been to events here before—art auctions with whiskey samples, benefit dinners with live bands and chocolate fountains.

The building sits at the corner of Rossville and Read Avenues. In 1903, when the cornerstone was laid, a “selected male quartette” sang the hymn “Speed Away.” A church history reports that the early congregation was composed of “staunch fundamentalists, friendly to the Wesleyan scriptural interpretation.” Rather than tithing, congregants attempted to raise money with ice cream suppers, meals-for-sale, and solicitations from the general public. The church became known as “St. James Grab-a-Nickel.” In the mid-1930s, according to the Chattanooga Times, the congregation “decided to try the Bible plan of finance, through tithing and the giving of offerings.” This proved more successful. By 1955, however, a “shifting population necessitated a move.” The building was eventually abandoned because the cost of coal heating was too high. It sat vacant for seventeen years, until its renovation in 2012. Coal heat was converted to electric and gas. A giant fan was installed (provided by the Big Ass Fan Company). There was so much coal dust ground into the floors, they had to be stripped.

I’d always assumed the Church on Main was just an event space, not a house of worship, but Sandi tells me a nondenominational church meets here on Sunday mornings. The church is called Relevant. “Define yourself radically as one beloved by God,” a recent tweet said, quoting Brennan Manning. “This is the true self. Every other identity is illusion.”

Business by week, house of worship on Sundays. Maybe this is one way in which the twenty-first-century church will survive.

Photograph by Maude Schuyler Clay

Photograph by Maude Schuyler Clay5

It’s one of the oldest churches in the city, perhaps the oldest all-black church, organized by the Reverend E. O. Tade with fourteen members on June 9, 1867, just two years after the end of the Civil War. The largest flood in Chattanooga’s history also occurred in 1867; it rained for four days straight in March just as the snow was melting off. The Tennessee River rose fifty-eight feet above its normal level. Bridges and telegraph lines, crops, and livestock washed away. You can read accounts of people being rescued from second-floor windows of the Read House, a historic hotel on Broad Street and MLK (then 9th Street). More than four hundred people drowned. One man stood halfway up the old Lookout Mountain road and watched bodies float past—one body per hour, he estimated. After the flood, the city had three options: build a levee, build a dam, or raise the town. Residents began the massive undertaking of raising a forty-block area of the city by an entire story. Today, in downtown Chattanooga, evidence remains of this buried city: summer sewage stench from runoff chambers that can’t be tracked, polluting foundry fill-material originally used to make the street level higher, tops of windows at ground level, basements with doors and windows to nowhere. In the basement of my gym, the Sports Barn, members can do their ab crunches on floor mats beneath several low-to-the-ground arches; these used to be the tops of windows.

Three months after the flood, a small group of men and women banded together to form First Congregational Church. One imagines the church rising out of tragedy: war and slavery and the recent natural disaster. This is my speculation—the founding members were all just-freed slaves and kept no written records. The earliest is a newspaper clipping from 1905, the year the current structure was dedicated, noting that five years after the church’s founding, cholera and yellow fever “so scattered and reduced the membership that there was not much more than a very small disorganized remnant left.”

But the church survived and grew to more than one hundred members until the civil rights era, when the youngest congregants began to get educations, some funded by church scholarships—and then moved away. Church moderator Wallace Roberson promised a group of eighty-year-old parishioners that he would help keep the church open as long as they were alive. The last of that group, a one-hundred-year-old man, died in 1999.

By then the church had dwindled to about ten active members. The final service was held on September 2, 2001, and the money from the church treasury was donated to the Chattanooga Community Kitchen, the NAACP, the Pi Omega Foundation, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, the Shrine Hospital in Lexington, Kentucky, and the Urban League of Greater Chattanooga. The building itself was donated to Fisk University of Nashville, which seemed not to know what to do with it. In 2006, Fisk sold the building to a developer out of Atlanta and used the profit for scholarships. The developer planned to turn the church into luxury condominiums. He painstakingly removed the stained-glass windows—more than 6,500 pieces of glass—and had them restored while the building was under construction. He also planned to rebuild the tower—forty-six feet high—that was originally on the building’s southeast corner but was removed in the 1960s to prevent debris from falling to the sidewalk.

Eventually, the condominium plans were scrapped and the church was restored as a for-profit event space, still in use today and known as Lindsay Hall. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2010. The tower was never rebuilt.

My favorite part of the history is the creation of a mural on the exterior rear wall, which didn’t survive the restoration. The huge painting depicted the face of Jesus, chin in his hands, protectively cradling a black child beneath him. In the early 1980s, a local artist named Andre Willis (who designed album covers for Stevie Wonder and the Commodores) had wanted to create the painting to memorialize the Atlanta Child Murders of 1979–81, when at least twenty-eight African-American children, adolescents, and adults were killed. Willis was the art director of the Highland Park branch of the Boys’ Club and a member of the Civic Art League. He painted the mural above the baptism pool at Mount Parson Baptist Church and served as the designer for the 1981 Miss Chattanooga Pageant. He said his prime aspiration was to be “another Norman Rockwell,” to “create emotion in people.” He needed one hundred gallons of paint to complete the painting. He raised the money by selling prints of a sketch of the mural for $50 apiece.

In the only image of the mural I’ve been able to find—a newspaper clipping showing Willis up on scaffolding, working on Christ’s beard—Jesus finally looks the way he’s supposed to look: dark-skinned and dark-haired and altogether human.

Photograph by Maude Schuyler Clay

Photograph by Maude Schuyler Clay

Six years ago, my daughter and I took the long road out the back of the mountain, all the way into Alabama. She was fifteen and had just received her driver’s permit; I wanted her to get up some speed. On the way back we took a detour and got lost. We saw a shack on the side of the road with pumpkins and gourds for sale. I figured as long as we were lost we might as well stop and pick some up.

That’s how I met the Watchman.

He’s old, somewhere in his late seventies, and claims to be a prophet. He’s also an artist, the visionary kind, with hundreds of paintings inside the cabin he and his son built out of reclaimed shipping crates. The roof is metal. He makes a living selling fruits and vegetables—but stop to buy something and you’re guaranteed a sermon will be thrown in free of charge.

His sermons take the form of visions, which he paints onto massive boards of plywood and reclaimed windows and cardboard and even gourds. Everything is material, everything is art. Since that detour six years ago, I’ve been going to see him—at first because I was fascinated by him as a character, but now because I love him as a friend and respect him as an artist.

And because, in my weaker moments, I suspect he might be what he claims to be.

Over the years, he’s shown me drawings of the U.S. prison system (circular, endless) and his vision of the internet before it was invented; bloated donkeys stuffed full of the earth’s problems, a bloated donkey with its mouth pried open and a giant hand stuffing the Lamb of God inside; and beehives filled with millions of soldiers who fly up to fight a heavenly battle. He’s shown me paintings of heaven, “up yonder,” where he says he often travels in spirit; an eagle’s talon sliced from its body, bleeding at the tip (“all that’s left of America”). Trees and gardens and flowers, always with weeds attempting to choke them out (“the enemy”). Paintings of pigs in a trough, their snouts buried in thousands of tiny husks (“corporate America getting fat off the middle class”).

After visiting all the defunct church buildings, I drive out to see him. He doesn’t attend any church, he’s told me. This here is all the church I need, he says, meaning his own ministry. When the growing season is over, the Watchman takes his visions on the road, somewhere in Alabama. I’ve never found out where. He lines up his paintings on the side of the highway, hoping passersby will stop to ask about them. At night he sleeps in the back of his van.

Today he seems quieter than usual, a little depressed. His feet have been bothering him. He warns me that the vision he’s going to show me is upsetting. It’s a drawing of a tree and its root system, the roots tapping into a collection of bottles. That tree is America, and them bottles are alcohol, he says. Whole country’s feeding on corruption.

Will you sing for me today? I ask him, sitting on the tiny church pew in front of the wood stove. I know it gives him a lift to sing for visitors.

’Course, he says. He pulls out his guitar and sits in a cushioned chair covered with a sheet. A TV-tray with an open large-print Bible is beside the chair.

Oh, can the Watchman sing. He sings “Little David, Play on Your Harp.” And he sings the Mulberry Tree song—which I think he made up, and which he claims he was singing when the Lord cured him of lung cancer. Today, his singing voice is softer than usual; he has to pause twice to wipe away tears.

When he finishes, I give him the gift I’ve brought: a thick Van Gogh art book with glossy reproductions of most of his paintings.

Do you know who that is? I ask, showing him Van Gogh’s self-portrait. (He often reminds me that he’s only “fourth-grade educated.”)

Yeah, I seen him in the spirit, he says. In a room with bars on the windows.

Your art reminds me of his, I say, turning pages. How he makes these swirls with his paint.

Beautiful, he says. Look at that. Glory.

When I leave, he walks with me to the car, limping on his bare feet.

You been a real blessing to me today, he says.

I tell him it’s the other way around. I tell him I’ll be back soon, and that I’ll bring him some more art.

After visiting all the churches, it’s the first time I’ve been to church.

I see other places of worship in my city.

I see Church of the First Born in St. Elmo, founded by the Reverend Alfred Johnson in 1978 and still growing, with new ground broken for a four-hundred-seat sanctuary; Beth Sholom synagogue, where my daughter has attended Shabbat services and bat mitzvahs with her middle-school friends, girls in their best dresses laughing together in the foyer; New City Fellowship on 3rd Street, close to my son’s school, which was founded in the 1970s by an interracial couple who grew up in the same housing project in Newark, New Jersey, and who devoted their lives to promoting cross-cultural worship and racial reconciliation in the South. I see the Mission Chattanooga on MLK Boulevard, held in a repurposed parking garage that serves as a coffee house/music venue during the week, place of worship on Sundays (it was a year before I realized my barista was an ordained minister); Second Presbyterian on Pine, with its beautiful gothic revival architecture, where I’ve stumbled, weeping, into Al-Anon rooms during a family member’s active addiction—keep coming back, it gets better, hugs and support from people whose names I will never know. I see the Islamic Society of Greater Chattanooga on Gunbarrel Road, whose members I stood beside in Coolidge Park last February as we raised our candles and voices in collective protest against the immigration ban; Our Lady of the Mount Roman Catholic, where all four of my children had their elementary school graduation ceremonies beneath the beautiful stained glass and Christ hanging from the cross; Church of the Good Shepherd Episcopal, whose parishioners organized the only People Power ACLU event on Lookout Mountain, which my husband and I attended, humbled and excited by the fierce commitment to social justice and political activism. I see the massive crowds with police directing traffic at Calvary Chapel on Broad Street, where my son used to hang out and skateboard, and where each year I’ve dropped off Christmas gifts for imprisoned parents to give to their children. I see weekly texts sent out by my own Presbyterian church, grocery lists so members can shop for the needy in our community.

All of it crying out Sanctus.

The day I am supposed to turn in this essay I find a newspaper in my driveway, wrapped in yellow cellophane. One of those small, advertisement-heavy throwaway papers that appears unbidden once a month. I’ve never looked at this paper in the twelve years it’s been coming. But today a headline catches my eye: ESTATE SALE. And here is Greg Ross, a full-page photo of him on the front page. The Estate of Confusion is closing its doors on May 1. Ross is selling the property “to an unnamed developer for an undisclosed sum so the buildings can be reused by an unidentified restaurant.” Everything in his store must go: hubcaps, huge camera lenses from Olan Mills. The giant stained-glass windows.

It’s my son’s birthday, and he wants to eat at his favorite burger joint, Slicks, which is next door to Ross’s place. My family goes inside to get a table, and I wander over to the Estate of Confusion, to see if the stained-glass Jesus is still there. But of course it is. Who would buy such a thing? For what purpose? For a split second I imagine bringing the arms-uplifted Jesus home and putting it in the living room beside my piano.

But God is everywhere, I tell myself. This is only an object. And I let the idea go.

Enjoy this Southern Journey? Subscribe to the Oxford American.