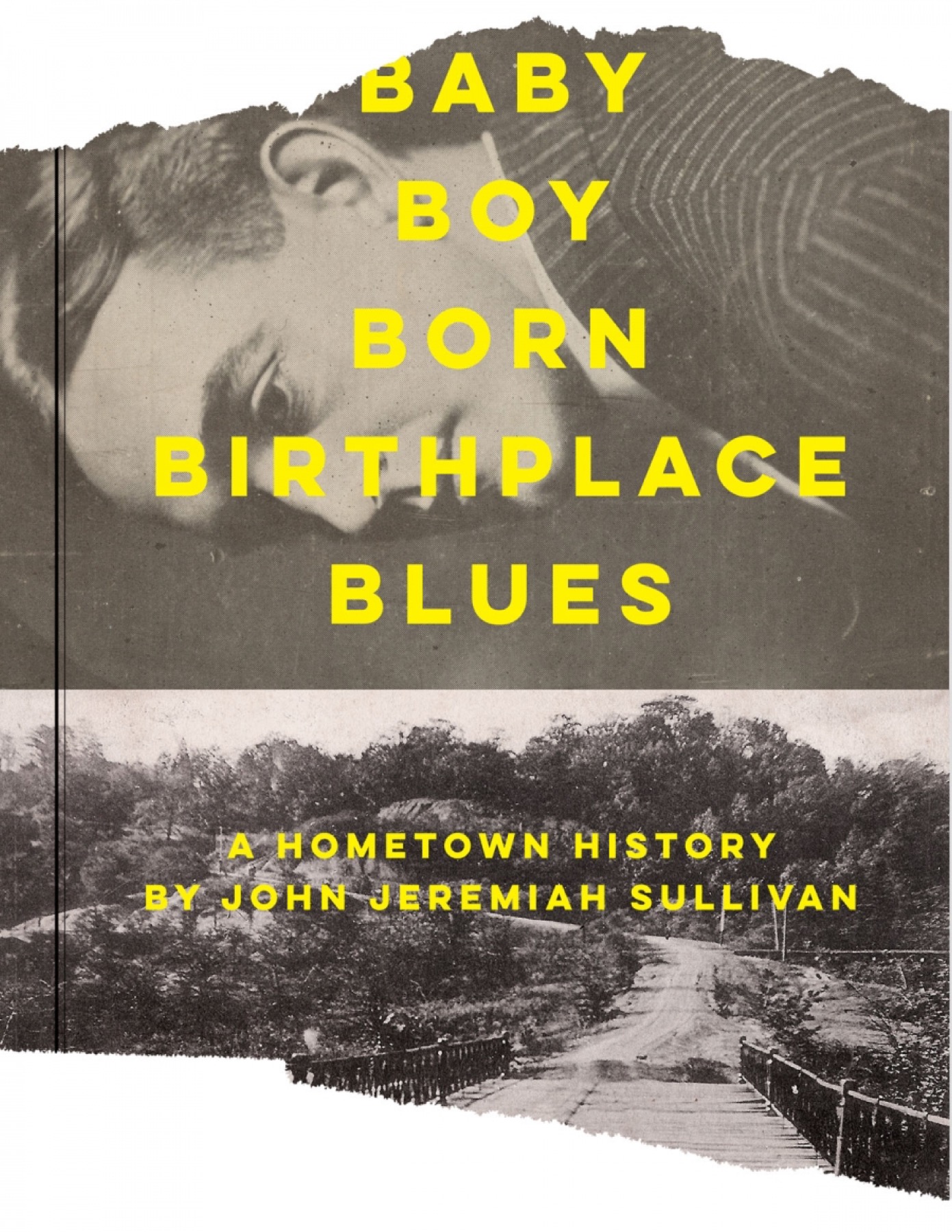

Baby Boy Born Birthplace Blues

By John Jeremiah Sullivan

Photos of Bert Kenney and Silver Hills, from the collection of the author

A Hometown History

The place I was raised in and where occurred the events that most shaped and damaged me as a human being was called Silver Hills. It’s a “knob,” as they deem the low hills in that part of the country. This one had used to be Cane or Caney Knob, so named because when the whites arrived it was covered in tall river cane. The cane is gone but the knob remains, and the people rechristened it Silver Hills, claiming as always that this had been the Indian name.

Silver Hills forms part of the little town of New Albany, Indiana, itself a kind of satellite city to Louisville, Kentucky. On a map or from a plane, New Albany looks like the northwest section of Louisville, but the Ohio River slithers between from the east and divides them, such that one section is Louisville and the other New Albany, one in Kentucky and the other Indiana, one in the South and one the North. My house and school were in New Albany, but my parents’ jobs and families—their own childhoods—were all in Kentucky. I grew up moving back and forth across a line that happened to coincide for a stretch with the Mason-Dixon Line, riding over the bridge in the backseat of a station wagon.

For blacks on the run from slavery before the Civil War, the distinction between those two riverbanks held an importance that went beyond questions of regional identity. New Albany was one of the places you hoped to reach on the Underground Railroad, one of the gateways to freedom in the North. Once you had crossed the river, you were out of the slave states. Beneath some of the old churches and houses downtown opened tunnels that led to and from the river. Free blacks from Louisville, disguised as fishermen, would row the fugitives over in the night, not even risking the faint glow of a dark lantern, and hand them off to their comrades or to New Albany abolitionists, who received the frightened people and moved them into hiding. When I was very young, an article ran in the local paper saying a boy about my age or a bit older had recently discovered another of these passageways. His family must have lived in one of the old river mansions. A lone detail stays with me: he was looking for Christmas presents. Suspecting they were hidden in a closet, he went rummaging when his parents were gone. He pushed at a certain panel and tumbled into a sort of cave and emerged hours later from a hillside overlooking the water. Some of that is probably imagined—it feels fluffed out—but the kernel is true.

Silver Hills, our tiny forested knob, had a part in all of that. In the side of the hill there was a cave, not a manmade tunnel but a real limestone cavern. I never saw it—people said it had been covered up, buried. By road construction maybe. Or the relocation of the river, because the Ohio had been diverted at some point, dramatically, when they built a dam. The farmland-looking campus of my junior high school, Scribner, had all been marsh two hundred years before. (Scribner: named for town founder Henry Scribner, who in a letter of 1827 recorded, disapprovingly, one of the clandestine methods involved in helping fugitives to disentangle themselves from legal slavery, namely false papers: “Persons slip over the river,” he wrote, “have regular papers of manumission recorded here and the negroes become citizens.”) Germans and free blacks had lived near the marsh, in a racially mingled settlement on the knob’s edge. The two communities reportedly “had a good relationship and used to help each other.” This is according to a source quoted by New Albany historian Pamela R. Peters, with whom I corresponded many years ago. She has since written a good book and some essays about my hometown.

On that hillside, up which I walked most days to get home from school, had been this unnamed cave—still was a cave, I suppose, way down, but you couldn’t see or access it—and slaves went there to hide. They weren’t really safe in New Albany, you see. They could shelter there for a while, but if they pushed their luck and tried to stay, the slave-catchers usually found them. Very hard to stay hidden when everyone knew a reward would be waiting. The townspeople would throw you in jail and wait for your Southern owner to come and claim you. Or if no one showed, they could send you to the slave pen in Louisville, make their money that way. Peters quotes a newspaper article from 1851 that reports two fugitive slaves who were “arrested in the knobs adjoining New Albany one day last week, and taken back to Kentucky, whence they came.”

The most dreaded of the Louisville slave-catchers was Robert Seay, a Fifth Ward cop who knew the black underworld intimately. He was the man you called when you heard that a slave had made it over the river. An item in the Louisville Daily Courier from the winter of 1856 describes one of his missions and ripples with unexpected detail.

That efficient officer, Robt. Seay, returned on Friday from Indiana, where he had been after some runaway slaves. He caught up with a gang of five at Bedford, Ind., and after a desperate fight captured two of them. Such was the wrath of the Abolitionists that he had to leave the town with his prisoners and walk through the night fifteen miles along the line of the railroad. The negroes had free passes, had bought tickets over the New Albany road in this city, and had written directions as to their line of travel in Indiana.

Reading on down the same page of the Daily Courier one stops at this:

Several runaway slaves have been arrested over in Indiana within a few days, including a likely woman, who had been passing herself off on the Republicans as a genuine buck nigger.—She was dressed and looked the man to the life.

No incident so well expresses the rare forms of social strangeness birthed in that arbitrary border world than the tale of the White Slaves of New Albany. The case has been mentioned in a handful of scholarly works during the past decade, but in 1850 it was an object of national fascination, reported and commented on all over the country. A family of three had been in New Albany for about four months—a woman in her fifties, her daughter, and the daughter’s son. They looked “white,” as we say, and everyone assumed they were. They lived among the whites. The little boy went to school and was thought “sprightly.” It was therefore a shock to the townsfolk when a farmer from Arkansas showed up one day claiming the three as his property. The Fugitive Slave Law had been passed just months before, the act that required Northerners to assist in returning runaway slaves to their masters (the slave system had been negotiating similar deals for centuries with the Indian tribes on its western fringes—we give you guns and blankets, you agree to catch our runaways for us—and now the whites were cutting the deal with themselves, a sign for anyone watching that it was all about to eat itself).

The New Albanians didn’t quite know what to do. The Arkansas man, Dennis Trammel (frequently mistranscribed as Frammell in both contemporary and recent academic sources), had his paperwork in order. The three were his slaves by law and had belonged to him for many years. And yet, the New Albany Ledger cried, “the so-called fugitives are, to all appearance, white persons!”

At first Trammel had tried to kidnap them the old-fashioned way. He arranged to have them “enticed” onto a riverboat and seized onboard, held prisoner as the Ohio carried them southwest toward Arkansas, back toward slave territory. They did not go quietly, it seems. They called out to the other people on the boat, or made their plight known by some means. They appealed not to their shipmates’ humanity but to their white pride. It wasn’t, Look, they are carrying us into slavery! It was, Look, they are carrying us into slavery! The other passengers were Kentuckians, after all, most of them, and probably slaveholders themselves. Their whole worldview was riddled with the ideology of white supremacism. To see whites enslaved was even worse than seeing blacks go free.

When the boat stopped at Hawesville, about seventy-five miles downriver, the passengers summoned local authorities. The sheriff had Trammel and his weird cargo forcibly removed from the ship. Word spread about the new arrivals, and a mob formed in the town square. After some hours of arguing and consulting with local magistrates, it was determined that the slaves should be temporarily taken from Trammel’s custody and driven back overland to New Albany, until the thing could be sorted out.

Back in New Albany, a judge put the family in jail. He summoned lawyers, and the lawyers summoned doctors. The doctors examined the three thoroughly but could find not a trace of blackness. The older woman, especially, looked as white as snow. “Some few of those who have seen the other woman,” said the Ledger, “think there is a slight resemblance to the Indian in some of her features, but a large majority are of the opinion that she also is of purely white origin.”

In spite of themselves, the locals had glimpsed something of the truth regarding the fugitives’ backstory. It was stranger even than we suspect. If you are like me, you have been reading this story assuming that the slaves will turn out to be from New Orleans or somewhere else in Louisiana, where there was a real creole culture, and where people with extremely light skin could still in some complicated way be considered “colored.” But, in reality, the family was white. That is, they had exclusively European blood. Well, I mean, God knows what kind of blood they had. They may have been Persian for all we know. But in the vast and grotesque scheme of classification that was and is American racial identity, they were whites—they were English or German, from Maryland. The older woman, at least, had been born in Baltimore at the end of the eighteenth century. Around 1825 she went with her husband somewhere south, we don’t know where, Georgia maybe. They could have been part of the wave of white settlers who helped push the Cherokee west on the Trail of Tears. All we know is that Indians killed her husband one night, out on whatever godforsaken outpost of the frontier he had mistakenly led them to. The Indians took the woman and her daughter as war captives, later trading them to the Seminoles as slaves. Trammel’s agricultural business had at one time involved supplying food to the Indian tribes, in the days when the government corralled them into concentration camps, prior to removal. He must have come to own the family that way. He’d bought them from the Indians. At least he had bought the two females. The boy may have been his natural son. For that matter, Trammel may have considered the woman his wife, but if so, it’s clear she didn’t return his desire. This was the kind of surreally interracial/multiracial thing that had happened all the time, back in the dark ages of the Early South—Carolina ca. 1704 or something like that. These people were late-surviving artifacts of that old world. Strange rivers had carried them to my hometown.

It was decided that, as odd and unprecedented as the case appeared, the law had to be obeyed. “Much sympathy was felt for the slaves” in New Albany, reported the Louisville Journal, “but they were delivered up without the slightest show of resistance.” In this the townspeople had, the Journal said, “behaved exceedingly well.”

Yes, the poor people were handed back over to Trammel. He smuggled them onto a boat as quickly as possible and took them straight across the river to Louisville, no messing around with a neutral river journey this time. A terrible ending, it seemed.

But then—a reversal. There was an outcry. People on both sides of the river professed themselves appalled at the outcome. You couldn’t treat white people this way. Indian slavery? That was something from their grandparents’ time. What mattered now was skin. No, the business could not be allowed to unfold like this.

Trammel, holed up in Louisville, became a figure of public scorn. He was probably sick of dealing with the whole mess. He let it be known that he would free the slaves for $600. Very quickly the amount was raised, with donations pouring in from New Albany and Louisville, too. The three white slaves were freed. They got on a ferry and came right back across to New Albany, where apparently they lived out their lives in peace. We don’t even know their names. Maybe they had no names, or a lot of names. They must have lived on the side of Silver Hills knob, by the fugitive cave, with the Germans and free blacks and other in-betweens.

Or did they shun those people? Were the white slaves embraced, perhaps, by the racist whites of New Albany, as redeemed captives whose whiteness had become meaningful to the community and needed insisting on in some way? The record is silent.

I find only one other reference to a cave in the forests of Silver Hills. The story sounds completely made up, the work of a half-drunk newspaperman who needed to file some copy around 1900, but amazingly, when you look in the New Albany census for 1870, the hero-character appears. Or rather he doesn’t appear, but his existence is noted, occupation given as “Recluse.” The story is from the lost Louisville Times and survives only by having been quoted in another source. “Years ago,” it begins,

Gilbert Vestison, the “Hermit of the Knobs,” lived on a wild and lonely spot at the summit of a hill. As a youth—handsome, intelligent, ambitious, and poor—Vestison had lived in France and had fallen in love with a girl named Madeline (whose last name he would never reveal). For a short time they lived in their own personal paradise, completely happy. Then Madeline’s wealthy parents parted their lovers. Gilbert was broken in heart and mind and became a wanderer. He finally came to the knobs, built a rude shack, and lived here for 30 years, nursing his grief and shunning the company of his neighbors.

Vestison became known throughout the neighborhood for his eccentricities. He said that he was 6,000 years old and that he expected to live another 1,000 years, after which he would be reunited with his Madeline in a second period of youth that would be unending. He was ordinarily gentle, kind, and apparently sane, but if a neighbor requested him to sing the “Marseillaise,” his eyes would glow madly and the battle song of France would roll from his lips in an impassioned torrent.

His cabin finally collapsed and he spent the last years of his life in a hole dug in the side of a hill. One morning two passing hunters found Gilbert dead in his cave, a smile on his lips. Near by were the remains of a log cabin and a huge pile of old shoes he had collected. Clutched in his hand was the photograph of a beautiful girl. Gilbert had lived his remaining thousand years.

* * *

The population of the African persuasion known as free niggers, seems to be rapidly on the increase in this city. Some of them will allow a white man to walk on the opposite side of the street from them if he behaves himself.

—The New Albany Ledger, March, 1862

Some of the fruits of the abolition agitation culminated at New Albany, Indiana, on the 22d. ult. Four boys between the ages of 18 and 20, were standing together just after night, when two negroes passed by smoking segars. One of the boys remarked, “them niggers are putting on a good deal of style,” but not loud enough, as they supposed, to be heard by the negroes. The negroes after this remark was made, turned and commenced firing on the boys with a revolver. The first shot fired struck a boy named Lansford in the calf of the leg, lodging against the bone. The second struck Locke in the left breast, killing him instantly. The negroes were subsequently arrested and sent to jail.

—The Hinds County Gazette

(Raymond, MS), August 13, 1862

We learn by passengers on last night’s train from St. Louis, that as they came through New Albany about 8 1/2 PM, the city was full of excitement, men running about drunk, adding all they could to the alarm, causing great fears of further rioting. The negroes are said to have all deserted the settlement back of the city, not a soul being left in it.

—The Louisville Daily Democrat, July, 1862

The excitement in New Albany in regard to the killing of young Locke continued all day yesterday. All day Tuesday parties of armed men and boys were parading the streets in search of negroes. Four negroes were badly beaten near the market house. Afterwards a large and excited crowd started to Dayton, a northern suburb of the city, where they found several negroes, all of whom were beaten, more or less severely, with clubs, bricks, etc., and one was shot, who, we learn has since died. A negro belonging to the ram Monarch, was also badly beaten. Seven other negroes were attacked and badly beaten by the infuriated people, a number of whom will probably die. West Union, a suburb of the city, was visited by a large crowd. Here a number of negroes were found, all of whom were badly beaten. On Tuesday night the crowd visited several negro residences, and destroyed all of their property—among other places the vineyard and garden of G.W. Carter, the barber, which they nearly ruined. On Tuesday night a large crowd visited the jail and demanded that the negroes there confined be given up. This being refused, they threatened to batter down the jail with a cannon, and at once proceeded to get the guns, but in this they failed. . . . The excitement was very intense at New Albany all day yesterday, and there is no telling when it will end.

—The Louisville Express, July 24, 1862

Exodus. The New Albany (Ind.) Ledger states that there has been a perfect exodus of the colored population from that city especially the males. The recent riotous proceedings there have had the effect to create a perfect panic among them, and every one who can do so is leaving.—Some thirty families have left, so far, and a large number of young persons who are engaged upon the river, but have made New Albany their homes, have changed their residences to Kentucky.

—The Athens Post (Athens, TN),

August 22, 1862

DRIVEN BACK.—The New Albany Ledger of yesterday says, that a number of runaway negroes arrived on the banks of the Ohio, below this city, opposite where a regiment of Indiana soldiers were stationed. The negroes stated that they were runaway slaves, and wanted to get into Indiana. The Hoosier soldiers informed them that if they attempted to cross the river they would fire upon them; that their object in going to war was not to make Indiana an asylum for negroes. The slaves skedaddled back into Kentucky.

—The Louisville Daily Democrat,

November 1, 1862

* * *

The blues was born on a riverboat between Louisville and New Albany, along those docks, in the 1890s. I mean, the blues was born nowhere, of course. Or it was born many places. Polygenesis: that is the scholar Jeff Titon’s term, and the closest we can get to the truth. Multiple points of origin, coalescing and coinciding. And contradicting! For instance, the blues is definitely black—from Africa via the culture of plantation slavery—and it is definitely an urban phenomenon marked by an inter-racial mingling of styles. It is definitely a “folk” phenomenon, born in the fields, and it is definitely a commercial product of the sheet-music era, born in vaudeville halls. It definitely has something to do with twelve-bar songs that have an AAB rhyme scheme in the lyrics and a I-IV-V pattern in the chords and weird bent notes at certain places in the scale, and it has absolutely nothing to do with any of those things, i.e., is correctly applied to songs that feature none of those qualities. These are not options to be chosen among, these are irresolvables, and there are scores of them. Stay interested in the old music long enough and you learn to live with them like rude in-laws. They are what Humphrey Lyttelton, the English jazz trumpeter and radio host, had in mind when he wrote, “There are moments when anyone setting out to discuss the blues must wish devoutly that the term had never been coined.” Most people think he was being funny, probably, but he was making a precise and necessary point. The thing we call “the blues” corresponds to the historical reality in about the way our modern term “Middle East” corresponds to the Arab kingdoms. It’s a term of convenience that’s not especially convenient, that’s confusing. “‘Blues’ has too many definitions,” said the jazz historian Gary Giddins.

Does that mean there isn’t a clearly identifiable musical tradition called the blues that’s clearly identifiable as black and clearly a major part of American history and culture? No, all of those things are real. That’s what I mean by irresolvable. You dive to the bottom of the pond hoping to find a little sphere of comprehension, but instead there’s a coin, and you can never see both sides at once. The myths can look deceptively like the fundamental truths, and vice versa.

For instance—the blues is Southern, its roots are there, and the deeper South you go, the deeper the blues. In many respects, this holds up, no matter how much you listen and no matter how much research you do. But it’s no less true that an awful lot of important moments in that early world of blues formation happened in a much less romantic place, in Midwestern or “mid-Southern” river towns. Sylvester Weaver, the first black performer to record a country blues song? A Louisville man, and recorded there. Mamie Smith, the first black woman to record a blues? A Cincinnati girl. Although she liked to tell people she was from Georgia (for blacks in the entertainment world, being as Southern as possible already had what they call “political economy”). One could go on, could build a grand case for the middle of the country, and in the end, the blues would go on being quintessentially of the South. But the minority report is fascinating. And it begins with the fact that one of the very earliest claims for a “first blues”—the first little lightbulb to flicker on if we’re looking down at the map of musical polygenesis—happens not in Mississippi or New Orleans or even Texas but along our section of the Ohio.

The story comes from John Jacob Niles, the Louisville-born composer and singer, and collector of early ballads. My grandparents came to know him, because he often performed at Christ Church Episcopal in Lexington, where they attended and where my great-great-grandfather had been the bishop. Even my mother remembers Niles some. I never saw him, though he lived until 1980. She remembers being told to sit still and listen to his music. He played a giant Appalachian dulcimer and sang in a high, warbly, eerie voice. “I Wonder as I Wander” was a favorite. His song “Go Away from My Window” gave Dylan the opening for “It Ain’t Me Babe.”

In 1930, in an essay for Musical Quarterly about “coon shouting” (as they called blues singing before they had the word), Niles wrote about the first blues song he remembered ever hearing: “The first shouter I ever knew was a Negress. That was in 1898. She did the current ragtime things, but was most effective in the native blues. Her name was Ophelia Simpson, although to me she was ‘Black Alfalfa,’ shouter and moaner in Dr. Parker’s Medicine Show.”

People question and sometimes unfairly dismiss Niles’s account, mainly for lack of evidence. But there was a Parker’s Medicine Show. At least there was one fifteen years after the time of his account, in 1913, passing through a place called Kenney, Illinois. (An advertisement survives.) There was, furthermore, an Ophelia Simpson. Not the most common name. She shows up in one of the Louisville city directories from the 1890s. She is identified as “colored” and works as a laundress. She was boarding on East Main Street, in a neighborhood that has since been erased multiple times, near the baseball stadium.

Niles remembered that she was married to a man named Henry Simpson, nicknamed “Dead Dog.” He was working at a fertilizer factory “up the river” from Louisville. That’s how he got his name, “Dead Dog.” The boneyard. In 1898 this would most likely have meant Read’s Phosphate Company in New Albany.

“One morning in the early winter of 1898,” Niles writes, “Henry (Dead Dog) Simpson was found dead. Ophelia was promptly taken in by two county patrolmen on a warrant charging her with one of the many degrees of manslaughter. I know it was 1898, because my father was wearing the uniform of the State Militia when he brought in the news about Ophelia being arrested. The Kentucky militia was being sworn in, it seems, with the idea of going to the Spanish-American War.”

When Ophelia got out of jail, she wrote and made popular a song about her dead lover. Niles describes it as “not burnt cork” but “their own native music.” It seems not quite believable, that he would have written all the lyrics down, when he was only seven years old. But probably his father did. His father in particular loved Ophelia’s singing, Niles said. She may have worked for the family. Who knows. Certain verses do sound authentic. For my part, if I may speak for once in my life with the authority of a native, I think she was real. I hear her voice on the river.

Put dat gun up beside of his heart,Put dat gun up beside of his heart,I said rough-ridin’ papa, we’re simply goin’ to part.

At exactly the moment Ophelia introduced her “Dead Dog Blues” and earned Louisville an unshakable place in the legend of blues formation, New Albany—and not just New Albany but Silver Hills—was making its own, more ambiguous contribution to the genre. It was in 1898 or ’99 that one Charles Elbert “Bert” Kenney made his debut on the minstrel stage. We can be confident he had heard Black Alfalfa sing.

His career in vaudeville lasted almost thirty years, a century in that business. He was a burnt-cork man—he performed in blackface. Called himself “Blue Bert.” His name was his own, but such a large portion of his act was brazenly ripped off from the more famous Bert, Bert Williams of Williams and Walker, that it almost seems like he must have borrowed it, too. Bert Williams was actually black—Bahamian, to be precise—but he performed in blackface. By wielding it as a mask, Williams became one of the more original stage artists of his day. In 1906 he introduced his classic, the existential “Nobody.” Kenney then started doing a bit called “I. R. Nobody,” in which he would discuss deep philosophical questions with an invisible, nonexistent interlocutor. “Kenney comes on in blackface,” said a Montgomery, Alabama, newspaper, “walking slowly and solemnly, carrying a slender bamboo cane, and pretends to carry on a conversation.” You get the sense that, for theater owners, hiring him may have been a way to get Bert Williams onto your stage without actually having to hire a black man.

And yet . . . he was talented, Kenney was. He had something. In the white press, at least, he won raves; it’s no exaggeration, his blurbs in Variety are staggering. In Nashville, where they’d seen it all, someone wrote in 1917 that if there were “better blackface acts than the one that Bert Kenney is putting on up at the Princess . . . they surely have given Nashville the wide berth.” A critic in Denver was so impressed he coined a new verb, writing that Kenney was a “relief after having witnessed some black-face comedians try to comeed.”

The thing that set Kenney apart, white audiences agreed, was that (to them) he actually seemed interested in African-American speech and habits. His act was seen as less mocking than the other blackface shows. He worked subtly, “without exaggeration.” A critic in San Francisco wrote about Kenney, “He trips you up Joyfully, but when you pick yourself up you are not angry, as sometimes you are with Al Jolson, for the spill into laughter has never been vulgar.” In 1909 he had participated in a public challenge. It was him against Jack Johnson, the famous boxer, “No, not to fight but for a contest of Negro Dialect.” Kenney was proud of his “study.” His own ad proclaimed that what he did was “NOT Blackface Comedy, BUT a True Delineation of the Real Negro Character.” Which suggests both ambition and shame.

In Richmond they found “his faithfulness and naturalness in interpreting the famous negro ‘blues’” to be “startling.” In 1920, the San Antonio Evening News went farther than anyone, writing that, “Mr. Kenney . . . is known as the original ‘blues’ singer.” He did “Hesitation Blue[s],” the “negro classic,” as it was already considered to be by then. (Nobody knows exactly who wrote it. If you were to hear it, you’d recognize it, with its blunt but universal refrain: “How long do I have to wait? / Can I get you now, or must I hesitate?”) Kenney made a specialty out of that one. It was, a critic in New York City wrote, Kenney’s “own idea of ‘blues.’”

To spend several nights following him through the entertainment press of the nineteen-teens was fascinating and dark, and knowing so well where he was from, where I am from, intensified that. A critic in Oregon somehow captured the flashing racial-funhouse atmosphere of the experience: “Blue Bert isn’t really blue. He drives blues away. He’s black. It’s hand painted black, and is no more real than his claim of blues.” His blackface was crude and offensive like all of it, but he was reflecting an ambivalence that had its own false authenticity, or authentic falseness, and was native to the place, to the borderland.

One of his glowing reviews includes a brief interview with him, a memory of his boyhood days in New Albany, hazy and self-mythologized maybe, but it exists:

Way back yonder, when Bert was a little shag, he took his life in his hands to get on the Inside of this blackface stuff. According to Bert, several blocks from his home a bunch of “Gabes” congregated and would sing all the latest songs in their own way. Bert’s room was upstairs and he had to slip out the window and slide down the roof to get away from his dad, who evidently didn’t think much of Bert as a blackface in those days. In this way Bert got the ideas he now is interpreting in his “Hesitation Blues.”

I have no idea what Gabes are. I’ve looked everywhere. New Albany slang? Is it racial? It seems like it is. It seems like the writer is saying that Kenney had experience singing with real black people. Gabes?

Then there is this, in the Charlotte Observer, 1918: “He is the unsurpassed master, so they say in singing negro ‘blues’ and sings them as if he really grew up in the Mississippi delta, or somewhere in the faraway south where the well known ‘blues’ melodies are indigenous.”

By the time the twenties rolled around, Blue Bert’s appeal was dwindling. The Chicago Daily Tribune made fun of him in 1921. “Bert Kenney,” they said, was a “survival of the burnt cork era.” He was also “an encore hound. If you even think of applauding him, he comes back.”

His last twenty-five years don’t seem to have been very happy. I hope that’s wrong. He worked as a greenskeeper at the country club. He did radio monologues about baseball for a local sports station. People knew he’d been famous once. Blue Bert! Folks liked him. In 1934 the governor appointed him a Kentucky Colonel. “He can never be real blue,” wrote a social columnist in Louisville, “with the disposition he possesses.” His wife died, his daughter moved away to California (she was a screenwriter—she wrote for The Bob Hope Show). Kenney’s health wasn’t great, his lungs. He got lonely.

In 1948 he took his own life. It was reported that he’d shot himself in the head with a .32-caliber pistol. His brother found his body in the kitchen in the middle of the night.

He had grown up in downtown New Albany, on Pearl Street, near the river, but in the last decades of his life he moved up to Silver Hills, to a “hilltop cottage” (according to his obituary) on Old Vincennes Road. Edwin Hubble, of the Hubble Telescope, did some of his early stargazing there, in fact had been doing it during the very years when Kenney trod the boards in blackface. This is the Hubble who later realized that the universe is expanding, that everything is destined to end in total cold and darkness. He taught at the high school, where my brother went. He lived in Louisville but had become close with a couple of families whose houses were in Silver Hills. One family especially, the Hales, kept a cot for him to crash on, he spent so many nights there. He showed them the planets through a borrowed telescope.

And that’s where Blue Bert’s brother found him, high on the former Caney Knob, where poor Gilbert Vestison died smiling in his hole, dreaming of his Madeline, and the fugitives hid in their cave (when you could still find it), there in the woods where I spent more of my youth and more happily than in any other spot, on an obscure lump of earth but like every patch of land, having its history and blues.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.