South Towards Israel

By Andrew Paul

It was tough not to stare at the spiraling lines of intricate tattooing on Marshal Klaven’s forearm as he ordered a pink lemonade at his favorite Tex-Mex spot in Galveston. We’d just come from Friday night Shabbat services at B’nai Israel, where Rabbi Klaven led a full chapel in a modern service, conversational and low key, with acoustic guitar renditions of Psalms interspersed among centuries-old prayers. The tattoos are just one of the ways Klaven conveys his signature merging of old and new traditions—a provocative attempt to infuse progressive theological meaning into an act stigmatized long before the Holocaust imbued it with memories darker than any pigment. Klaven inked his left arm nearly six years ago, after finishing a controversial rabbinic dissertation on the allowance for Judaic tattooing. For a design, he chose the V’ahavta prayer in Hebrew, a central liturgical passage recited daily by the observant:

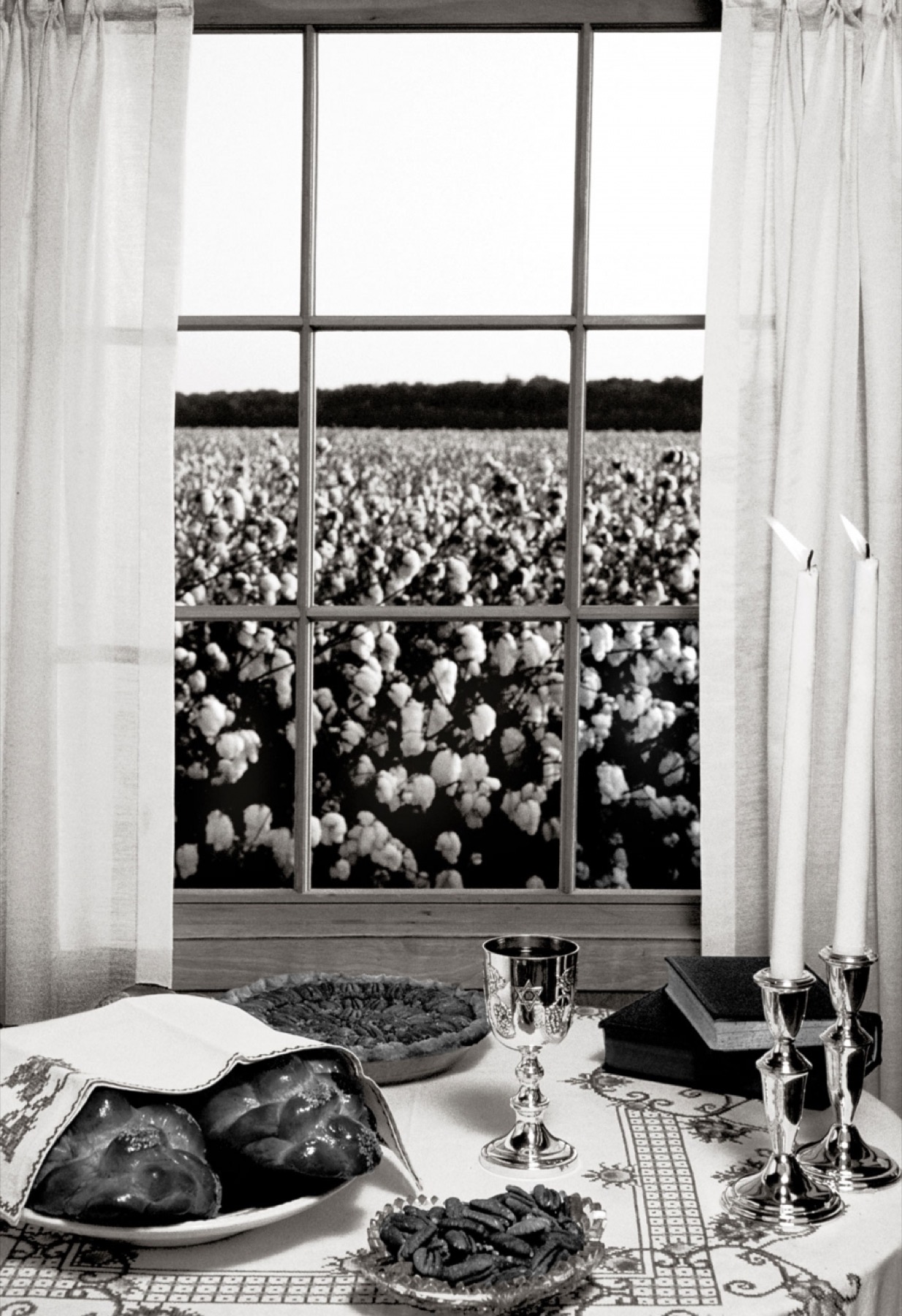

I often wonder what’s left for the Jews of the Deep South. How many of us have strength enough to love our God? The smaller communities are diluted, if not evaporated completely; few Southern Jews choose to stay in their rural hometowns, while fewer practice their faith with any regularity. In Mississippi, where I’m from, Natchez’s beautiful historic synagogue opens only intermittently for Shabbat. Almost all the Delta children raised by post-Shoah parents have left for opportunities outside the nation’s poorest state. Vicksburg’s once thriving Jewish middle class has shrunk to a handful of aging bubbes.

I grew up in Clinton, where I was one of perhaps four Jewish students in the school district, my brother included. I was, at the very least, the lone Yid for five grades in either direction, and as such, the sole representative for all Judaic inquiries, critiques, and jokes. It wasn’t until I heard Marshal Klaven’s story that I realized the very obvious—living in a larger shared community doesn’t necessarily make the Jewish experience easier.

Over chips and salsa, Klaven spoke matter-of-factly about the alienation and anger he experienced during his own adolescence in St. Louis: “I had already been in the back of a cop car at fifteen. Made some useless attempts at suicide around that same age, but they were more cries for help than anything.” Although he was raised in a Jewish household, he largely resisted the faith. He found an opportunity to get the hell away from home when, in 1995, at age sixteen, he was invited to travel to Israel for three months.

Once there, he saw Judaism as daily life—regular practice as positive and meaningful. “I just wanted to somehow be away from this world,” he said. By the time he left Israel, he was observing again. “Maybe there was a point to me being there. Maybe. I was willing to start entertaining it.”

The contradiction Klaven embodied in adolescence—the desire to be away from the world coupled with the inherent impulse to somehow stay a part of it—speaks to the modern Jewish paradox: How integrated can a self-identifying Chosen People ever really be? As an adult, I’ve identified myself almost exclusively by being a Jew, yet I take umbrage at being singled out for any reason. I had come to visit Rabbi Klaven in an attempt to reconcile this irony, hoping to find some kind of model in his story.

Into his early twenties, Klaven connected more strongly with his faith, exploring Judaism in his spare time, although “in an innocent and naïve way,” he reflects now. He returned to Israel in 2001, but the spiritual foundation he had managed to build eroded just as quickly as it began. The trip corresponded with the Second Intifada, and the country he had fallen in love with as a wayward teenager was now tortured and struggling.

“They were truly ugly to one another. Palestinians to Israelis, Israelis to Palestinians, Israelis to Israelis,” Klaven told me. “They were angry, they were fearful, and they just responded from that place.” He witnessed the hatred, distrust, and contempt up close: bombings threw blood and severed limbs across stone streets; a brutal shooting occurred outside the kibbutz where he lived. After his return to the States, he told no one about what he saw. Classic signs of PTSD started to manifest in his daily life and relationships.

Klaven believed himself finished with Judaism and God. He withdrew, seeking only the kind of work that required minimal human interaction: stocking grocery store shelves, flipping burgers as a line cook. At his mother’s urging, he took a job at a summer camp, where he spent time with a child suffering from severe physical and mental disabilities. During those weeks, the relationship he built with the camper rekindled something within him. As he explained it to me, he knew then that faith couldn’t simply develop interiorly; he needed to practice for the lives around him. One of Judaism’s largest focuses is the concept of tikkun olam—healing the world—and it was this that ultimately saved Marshal Klaven.

“I blamed God for all these humans doing really shitty things to one another, when in fact God gives us the ability to do both the bombings and to put us back together,” he said. “I signed up for rabbinic school and never looked back.”

In 2006, Klaven enlisted in the Air Force. (The U.S. military has a program aimed at increasing religious diversity within the ranks by allowing recruits to complete seminary training while enlisted.) Three years later, as an ordained rabbi, Klaven began assisting service members suffering from PTSD in their transitions home from redeployment. The military work helped him cope. He said, “What once was a very cursed experience became very rich to me.”

The southeastern Texas landscape is a buffer zone between the Louisiana subtropics and the West’s desert emptiness. The geography of Galveston is a mix of brackish bayous, sand dunes, and parched grasslands. In any given direction innumerable oil refineries erupt out of the horizon like metallic mirages, constant reminders of the area’s increasingly precarious economic future. Markets, flooded with surplus foreign crude, have slowed the domestic industry to a crawl. In the summer the city swells to upwards of a quarter million inhabitants, but the off-season sees fewer than fifty thousand year-round residents. Drug trafficking and usage, especially in methamphetamine, have risen since Hurricane Ike struck in 2008. Occasionally, narcotics bundles worth millions wash ashore from the Gulf of Mexico.

Galveston is built over the ruins of Campeche, the pirate Jean Lafitte’s infamous island colony. A notorious smuggler, Lafitte operated along the Gulf Coast, for years evading the law. During the War of 1812, he offered naval assistance to General Andrew Jackson against the British, and President James Madison granted Lafitte a tenuous pardon after he helped save the city at the Battle of New Orleans. But by 1821, U.S. naval forces evicted the pirate and his supporters. They razed Campeche, making way for a new city.

Rabbi Klaven drove me around Galveston’s quiet boulevards after dinner. In the years since Hurricane Ike’s devastation, the storefronts have been rebuilt with faux-historic authenticity. Kempner Street, a main road leading toward the channel, is named in honor of one of the first prominent Jewish families. Ashkenazim prospered in the mercantile and shipping industries while integrating into the port town, becoming part of the community’s backbone without sacrificing their ethnic heritage. B’nai Israel is the oldest reform synagogue in the state, serving Galveston since 1868.

Klaven pointed out his congregation’s original building, part of which still stands today as luxury housing, attesting to the wealth and influence the Jewish population once wielded. Between 1907 and 1914, more than ten thousand Jews fleeing the pogroms of Eastern Europe and Russia passed through as part of what became known as the Galveston Movement. Many immigrants started new lives in the country with the help of B’nai Israel’s second rabbi, Henry Cohen.

Just five years ago, B’nai Israel was on the verge of disappearing—after Ike, some congregants moved away, and others had disaffiliated or lost interest in the idea of Southern Jewish identity. The community faced an uncertain era when Jimmy Kessler, the congregation’s beloved rabbi of nearly thirty years, retired in 2011.

After his Air Force commission, Klaven was working for the Jackson, Mississippi–based Institute of Southern Jewish Life as an itinerant rabbi serving underfunded Jewish communities around the Deep South—places like nearby Natchez and Greenwood, and as far away as Tennessee, Louisiana, and lower Oklahoma—when B’nai Israel came calling. (It was during this time that I met Klaven, when he would occasionally serve as substitute rabbi at Beth Israel in Jackson, the city’s one synagogue.) Though the work had been rewarding, the travel was difficult on his young marriage, and he and his wife, Christina, were ready to put down roots. They moved to Galveston in 2014.

Teachers, friends, and fellow rabbis all advised Klaven to refrain from making any large changes to the congregation during his first year at the synagogue. As he told it, the advice he got was, “Don’t mess with what they called the ‘sacred cows,’” which included everything from the sanctuary’s layout to fund-raising models. Recounting this, Klaven smiled and pulled his shirtsleeve over his tattoos as he gripped the steering wheel. “What if you enter onto a ship that is sinking, or it’s sailing toward some big obstacle? Are you just supposed to give it time? So what were we to do, man?”

Over the next few months, Rabbi Klaven and his board changed mandatory membership dues to a pledge model, built a lower pulpit, and made religious school free. They commissioned a redesign of the synagogue’s website and logo, along with a host of other alterations. Since then, with the help of his congregants, Klaven has brought the temple back from the brink of closure, seeing nearly forty families join or return to the community. This may seem a small number in the land of megachurches, but it represented an immense growth for a Southern Jewish enclave like B’nai Israel.

After the tour, Klaven dropped me off at my truck, but before I got out, we idled for a time, talking about Mississippi. “In all these places I used to visit—Natchez, Vicksburg—Jews were very much integrated into that Southern fabric. They were just, ‘the Jews,’” he said. “I always make the point: no one seems to care if you went to Protestant church or, as they would say, the Jewish church. Be a faith-believing person, and during the rest of the week it didn’t matter.”

He brought up Rabbi Henry Cohen, the man instrumental in shaping Jewish life in southeastern Texas: “Late in his career, he stood arm-in-arm with the bishop and blocked the Klan from coming onto the island. He integrated himself into the community. He was representing all Jews. And in much the same way, it’s my charge—if you’re going to be allowing our values to become of influence, you can’t stick behind the walls of your temple.”

The pirate Jean Lafitte’s demise is a matter of historical contention. Most historians believe he died in 1823, shortly after ceding Campeche, from wounds sustained during a battle off the coast of Honduras. Others insist he succumbed to fever a few years later on an island near the Yucatán Peninsula. This debated detail may have fueled the emergence of one of piracy’s most controversial artifacts, The Journal of Jean Laffite, a French account introduced by an equally enigmatic and contentious individual, John Andrechyne Laflin. A largely illiterate retired railroad worker from Missouri, Laflin submitted the diary to the state’s historical society in the 1940s, claiming he found it among his family archives. Translated into English, the text repudiates all previous assertions about Lafitte’s final days. Here Lafitte renounced his violent tendencies and opportunistic profiteering for an everyman’s life in the heart of America, dying in the 1850s not from sickness or war injuries but from old age, while living in Illinois under a false name. It also shed light on the pirate’s origins. “My grandmother was of Spanish-Israelite descent,” the supposedly aged Lafitte recounts early in the diary, adding that his ancestor remembered vividly their family’s persecution at the hands of the Inquisition.

For a brief window, the diary aroused historical interest, but today Laflin’s “discovery” is almost unanimously considered fraudulent. Although experts maintain Laflin wasn’t shrewd or talented enough to have forged the book himself, evidence indicates that the journal is a fake, an amalgam of available history with inventive revisions. Nothing new in the journal has been, or likely will ever be, corroborated. But someone thought it important to alter this man’s life, to change his facts. He or she would humanize Lafitte, make him struggle to be charitable and kind, remorseful for the past but hopeful for the future. For some reason, they decided to make him a Jew. I can’t help but imagine a lonely young Semite penning the pages of an icon that never really existed in the first place.

After Klaven and I parted, I took a stroll through the city on my own. A building thudding with bass drew me in: the Buckshot Saloon. Inside was a cavernous hall modeled after classic honky-tonk bars, complete with a smooth, wooden floor for line dancing. I sipped a beer at the bar and watched as couples two-stepped counter-clockwise across the stage.

“Nice tzitzit,” someone said from behind me.

I turned to see a man my age pointing at the tassels hanging from my undershirt.

Richie, in starched Wrangler denim and cowboy boots, was an oil-tanker-working, Libertarian-sympathizing, card-carrying member of the NRA. And, as it would happen, a devout Jew. He told me his family was from New York, where he attended shul for a time. He moved to Galveston with his mother when he was a child. Richie said he was proud to be a Texan, but he wouldn’t remain here for long. Enlisted in the Navy, he was about midway through pursuing a chemical engineering degree. “As soon as I can, I’m packing up and committing Aliyah,” he said, referring to a Jew’s religious, permanent relocation to Israel. “I’ve visited there before, and I’m in love with the land. I can’t wait to go home.”

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.