La Belle Rivière

By C. E. Morgan

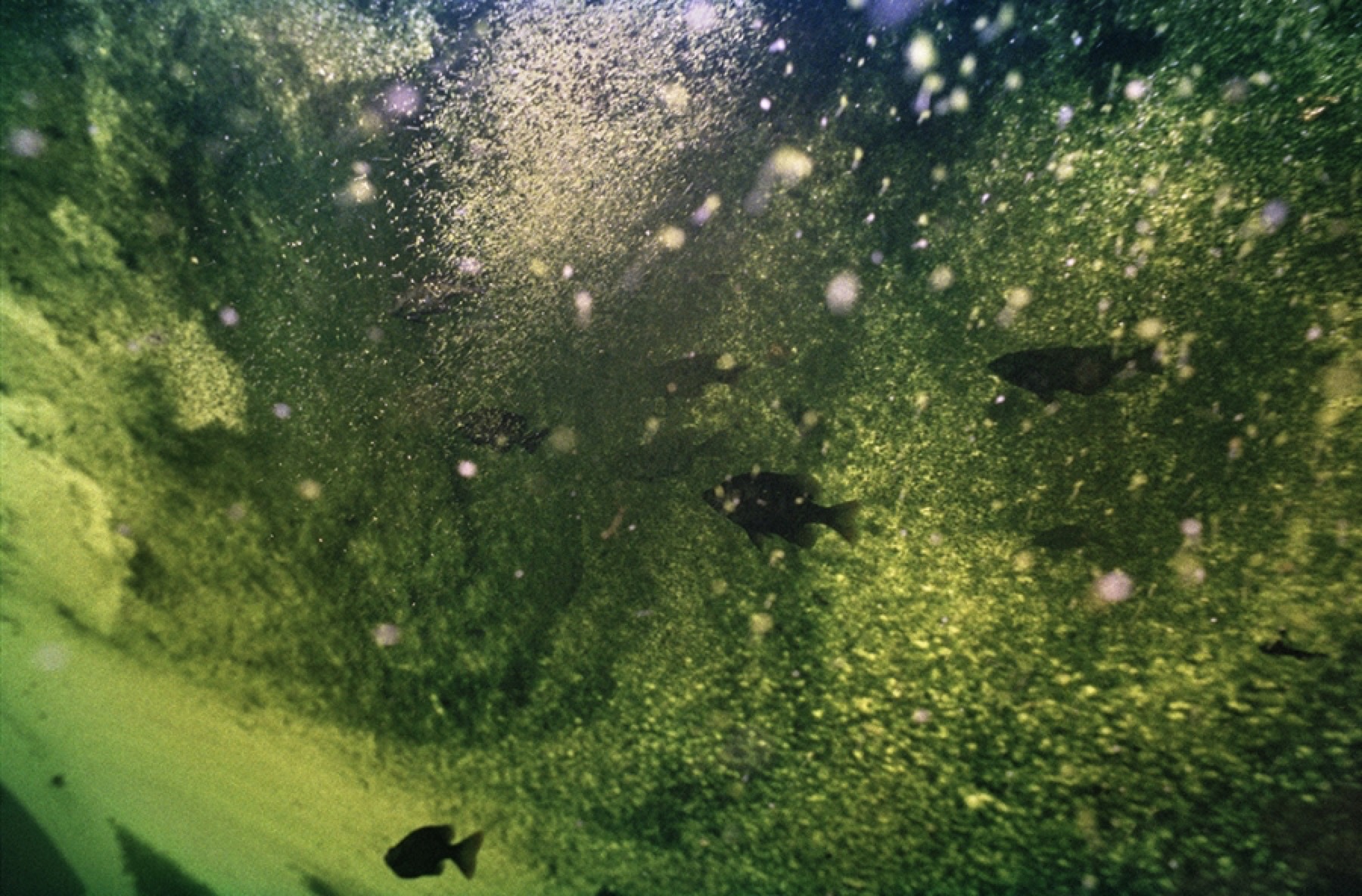

La belle rivière: the Great, the Sparkling, the White; coursing along the path of the ancient Teays, the child of Pleistocene glaciers and a thousand forgotten creeks run dry, formed in perpetuity by the confluence of two prattling streams, ancient predecessors of the Kentucky and Licking—maternal and paternal themes in the long tale of how the river became dream, conduit, divide, pawn, baptismal font, gate, graveyard, and snake slithering under a shelf of limestone and shale, where just now a boy is held aloft by his beautiful father, who points and says, “Look!” and the boy looks, and what he will remember later is not just the river like a snake but also the city crowding it, and what a city! A queen rising on seven hills over her Tiber, ringed hills forming the circlet of a crown. A jagged cityscape of limestone and brick and glass with a bright nightless burn. The buildings never shut their brilliant eyes to the river where not so long ago, a teeming white mass came floating down to topple trees between the Great and Little Miamis and garrison pike-forts and sling tart, poison arrows at the wegiwas, those brown beehives up in flames. What freedom to rename the named! Losantiville, or Rome, or Cincinnatus after that noble man who would not stay in Rome, but returned home to his plow on the grange. In his stead, they crowned themselves and an American queen was born, one free of Continental dreams, the first to climb off the king’s cock. Visionaries and confidence men alike launched down la belle rivière in droves. Lawyers and stevedores and sawyers and preachers and masons and Methodists, Lutherans, Baptists, and all the rest; the pious came with the venal, the wealthy with aspiring merchants, and the poor came by the thousands as well, passing women lap to lap on flatboats crammed with china, bedsteads, chests, and hogs to the gunnels that dipped and threatened to tip as they rounded broad bends in the river, curving down through the Territory to the Miami Purchase with its terraced bottoms and towering heights. More green than will ever be seen again, and the chance—now forgotten—to peer straight down through the pellucid Ohio, so sunshot and numinous and strange, it was like peering into bright time itself, right into the eyes of an engorged staring catfish not of this age but of millennia before, darting momentarily through a dream no Boston or Philadelphia could offer. Sooty, city-ravaged fingers dip into the cool river water, then the fish darts off and disappears forever, and the Kaintuck at the pole cries, “Coming! Coming nigh!” and there she is, the city—fat, pale, concupiscent, a white intrusion into the billowing green. The newcomers drive all their pigs into her. The swine befoul her and roam wild into the seven hills and beyond, where they breed: doubling, trebling, making a second city of swine. On the low banks of the river, blocks south of the new brick residences, the citizens build their first abattoir and in the years to come rangy drovers will drive tributaries of pigs down off the shale hills and out of surrounding valleys, make fat rivers of flesh in the streets so wealthy women will refuse to leave their homes for all the shit. The drovers come hollering, and the pigs, thousands upon many thousands of them, squeal in pink and brown and black waves until they reach the muddy river embankment, where they surge around carts, wagons, barrels, and horses only to be beaten and funneled stiff-legged onto a wooden ramp that runs up the full four stories of the meat house. Whacked steadily from behind by the drovers’ staves, each wave of squealing hogs pushes the hogs ahead of it to the slaughter, scrambling and pressing up the stinking ramp made slippery with green shit. Now the first hogs smell base blood over excrement, but are forced ahead into the shadows of that first and last chamber. A bloody-aproned man moves in menace at their far reaches; then one animal is gripped at the pastern above the cloven hoof and dragged, screaming, its left leg clasped in metal, now hauled up by a pulley with a shattering cry, its own weight ripping ball joint from socket so it hangs distorted at the thick hip, screeching its final confession, eyes bulging wide as its neck is sliced and blood jets from its jaw and runs into its eyes. Unable to pass through the slit trachea, the air whistles uselessly. The pig jerks madly and is soon drained pale, eyes bald of life. Now the next one and on and on. All hanging in a line, swaying side to side along the pulley as their bodies are opened, showing waved lines of rib and vertebrae like the keys of a warped piano, the heads sawn off. Now to the disassembly: a drop onto the table, then quick mechanical thudding, the fall of cleavers, the flinging of component parts—hock, shoulder, loin. In sixty seconds, the hog is gone and meat is made, the dumb passage of life.

Up city, up boomers, up commerce, uphill the city is built. All the hands of Bucktown come to build it: the escaped, the manumitted, the somewhat free who live in the Bottoms between Sixth and Seventh, backed up against the putrefaction of Deer Creek. After the barrels of pork are shipped to South America and the Continent, the abattoirs haul the remnant, decaying offal up the hills above the creek and make a foul graveyard of the fresh, verdant hillsides; blood and bone and bits of mottled porcine matter tumble down the hills with each rain and make a hellish clog of the creek. Bucktown smells like an open coffin.

The workers emerge from the neighborhood every day; the women walk north away from the tale-telling river to clean and cook at the stately homes on Sycamore and Broadway, and the men gather near the market to be selected for work. The Bavarian contractors survey the stock: here are talented roustabouts and stewards and draymen, but all previous lives count for nothing toward the task at hand. Bucktown will be the builder of the first truly American city. He builds the storefronts on Main, the townhouses on Race and Spring, where, when he stands on the upper scaffoldings and stretches upright with his hands to the aching small of his back, he can see the dark, whispering river in the distance. He labors. He labors and the city grows. But whenever his own numbers swell, he’s chased back into Bucktown, his clapboard home burned, some of his number left swinging from lampposts. And when the smoke clears on his dream of the North, he returns to the work site, builds red Music Hall side by side with the Germans, who will celebrate their symphonies and sopranos within its soaring halls after hours when he is back in Bucktown bedded down with his wife. Through wars and decades, he labors: Richardsonian stone and Queen Anne, Flemish bond brickwork and brownstones until the city is built up the sides of her hills, the new century’s clapboard houses rough jewels in the Queen’s crown. Any man working on the bluffs possesses a commanding view of the wide river, and beyond it, the fretful, historied amplitude of Kentucky, that netherworld. But soon enough skyscrapers will interrupt that view and they grow so thick, like a forest of glass, that no one can see the river anymore unless they stand on the fossilled outcroppings that jut like limestone and shale parapets from the very tops of the hills where, now, the little boy is visible under the momentary aegis of one Mike Shaughnessy, truck driver, halfhearted lothario, collector of children, poor Irish agnate, known in high school as that fucking Irish fuck. This man possessed of a rare and undeserving beauty, the one man the boy’s mother had the misfortune of loving—end and beginning and middle of story. And now the boy, as dark as his father is light, gazes down at the city and its brown river that seems far too wide and far too deep to be swum but, oh children, it was swum.

Adapted from an excerpt of The Sport of Kings by C. E. Morgan, published by Farrar, Straus & Giroux on May 3, 2016.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.