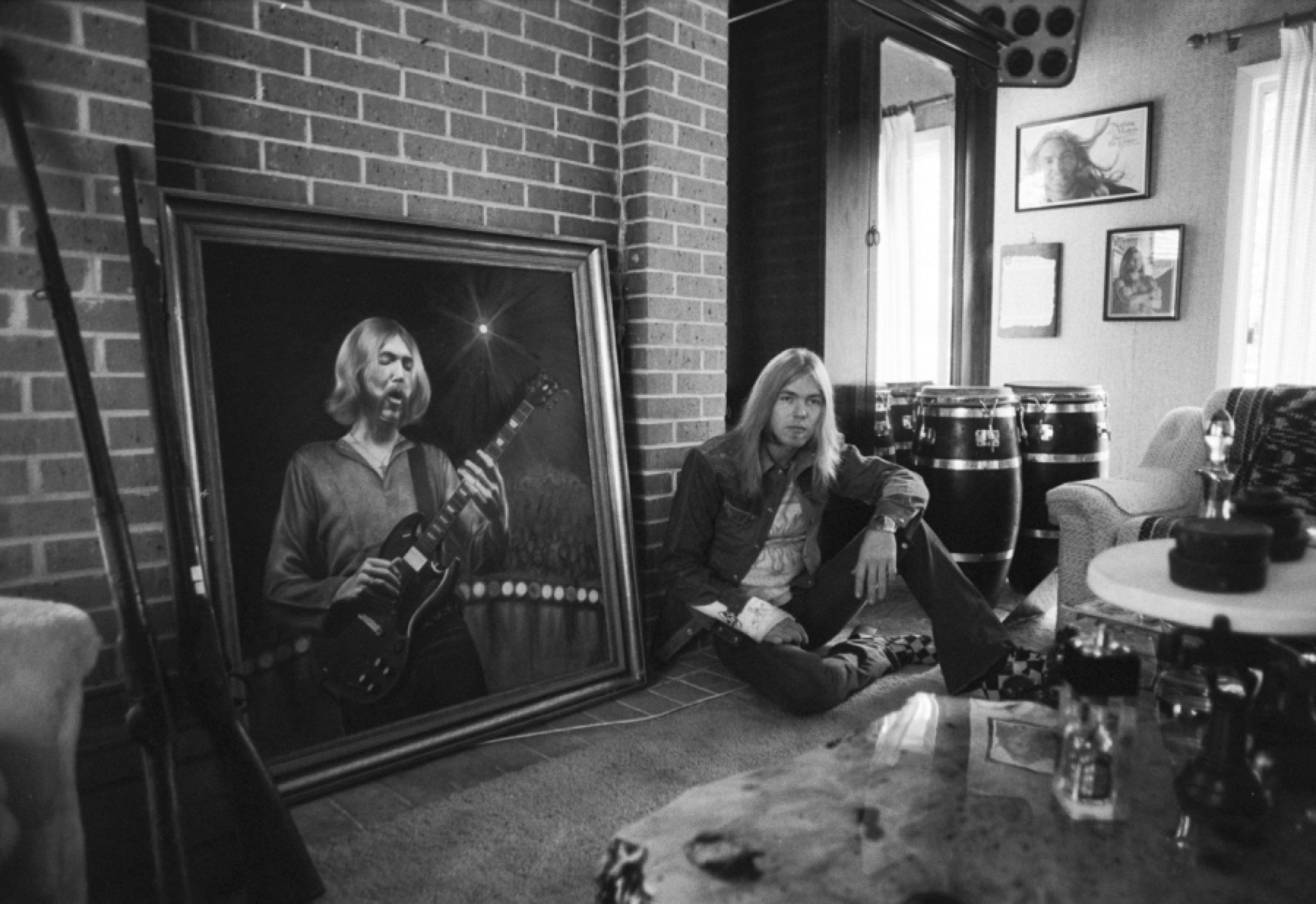

Gregg Allman with a portrait of his brother (1975). © Ken Regan. Courtesy of Morrison Hotel Gallery

The Road Goes on Forever

By Amanda Petrusich

I had this idea that I could arrive in Macon, Georgia, via rental sedan, nose around for a day or two, and figure something out about the South, and rock music in the South, and men in the South, and men, and death, and guitars, and the Allman Brothers Band, who, in the late 1960s, engineered a new style of rock music that was deeply and earnestly influenced by rhythm & blues but also by something else—some wildness I couldn’t isolate or define or deny.

I was coming to Macon from a book festival in Tallahassee. All weekend, I’d kept announcing to my hosts that I’d never spent any time in North Florida before, but that wasn’t entirely true: a couple years earlier, I’d spent two days chasing bigfoots—or the myth of bigfoots—around the Apalachicola National Forest on a goofy newspaper assignment. North Florida is the sort of place where bigfoots seem plausible, even likely. It is the sort of place you go to and then forget that you have been there.

Duane and Gregg Allman attended Seabreeze High School, a couple hundred miles southeast of Tallahassee in Daytona Beach, a spring break boomtown situated on what’s sometimes known as the Fun Coast (an appellation that evokes, for me, a whole cornucopia of not-fun things, like date rape and dismemberment). Daytona is beloved, globally, for its hard-packed beaches and motorsports. The air is heavy with ozone, exhaust, Coppertone.

Sometimes I think I can hear Daytona in Duane’s earliest guitar solos. There’s a sticky, melting-popsicle quality to those licks. When the sun rises in North Florida, everything slumps a little, dribbles: the live oaks saddled with Spanish moss, the condensation sliding down a Coors can, all of it bending back toward earth, ready to be swallowed up—to return, prodigally. I couldn’t catch a breath there. My hair curled. After a while, the atmosphere makes a person feel a little vulnerable. Any masks, actual or metaphoric, drip right off your face.

Duane was born in Nashville in 1946. Gregg followed one year and eighteen days later, delivered by the same doctor in the same hospital. Their father, Willis Turner Allman, an Army lieutenant and gunnery sergeant—he had crawled onto a beach at Normandy—was murdered the day after Christmas, 1949, when the boys were three and two years old. He was shot by a stranger he had met playing pool, had given a ride to. Details about the night are scant. Gregg writes about it a bit in his autobiography: “I don’t have the slightest memory of my father, nothing.” Willis’s killer, a dude named Buddy Green, likely told him to turn off onto some unmarked dirt road. Something happened, a botched robbery, everyone split. Green was a veteran, too—shell-shocked. He plugged three bullets into Willis’s back that night, then was caught and lived the rest of his life in prison. Geraldine “Mama A” Allman raised her two sons alone.

Young Duane was a quick study at the guitar, which he took up at age thirteen. Gregg had taught Duane his first chords on an old Silvertone from Sears—simple things, E, A, B, the three-chord turnaround—but, as he’s said, Duane soon passed him as if he were standing still. Whatever intangible, miraculous thing it is that separates a very good guitarist from a great one—Duane had that, in excess. I suppose it’s a kind of vulnerability: a willingness to be exposed down to the marrow, to live as if you were stuck inside an X-ray machine, with everyone always seeing all your parts and how you work. Listening to Duane, you get the sense you’re receiving everything he had, straight, that he was uninterested in or incapable of mediating his presence while playing. That’s Duane.

There is a posed photo of Gregg and Duane from around this time (they must’ve been high school freshmen). Save a height difference, they are nearly identical: blond and blonder. They started playing together, formed a duo, booked gigs up and down the strip in Daytona, first as the Escorts and then as the Allman Joys. They picked up a few more players, got started on the chitlin’ circuit. Duane dropped out of high school and prodded Gregg to do the same. Gregg wasn’t sure yet—he thought maybe he wanted to be a dentist. He graduated from Seabreeze, got accepted to a college in Louisiana. He agreed to give Duane a year.

The Allmans left Florida in the late 1960s, first for St. Louis, then Hollywood, where they signed with Liberty Records, a bum contract that kept them marooned in California for a while. Eventually, Duane wiggled out of the deal and took off for Muscle Shoals. He’d started messing around with a slide by then, running a Coricidin cold medicine bottle up and down the neck of his guitar. Rick Hall, owner of FAME Studios, said that Duane’s playing around this time “smelled like it came out of the bottom of the Tennessee River.”

Hall hired him as a session guy. One of his first jobs was backing up Wilson Pickett on a screaming cover of “Hey Jude.” There’s a photo of Pickett and Duane working together in the studio that day. Duane is grinning under a bushy mustache. He was just twenty-two. I can’t tell if Pickett is laughing or singing—his head is thrown way back—but he looks beautiful sitting next to Duane. The track is worth seeking out; Duane does some wild soloing during the coda. The na-na-nas are mercifully low in the mix. I wonder, sometimes, what Duane thought of the McCartney lyric “For well you know that it’s a fool / Who plays it cool”—if it made sense to him, if it resonated in a big way, as I sometimes suspect it might’ve. Pickett keeps hollering his face off, like some exotic bird.

For whatever it’s worth, Eric Clapton named Duane’s part at the end of “Hey Jude” his favorite guitar solo of all time. Clapton collaborated with Duane about two years later at a Derek and the Dominos session in Miami, recording “Layla,” a track about Clapton’s unrequited love for George Harrison’s wife, Pattie Boyd. Allman’s riff is celestial—it floats the whole song. “When you listen to that album, you notice that every time Clapton takes a solo and then Duane takes one and then Clapton comes back in, it seems like he has a hard time playing, like he’s had his mind blown,” Duane’s old friend, the guitarist Jim Shepley, told the journalist Jas Obrecht in 1982. “I really think Duane messed his mind up.” Duane doesn’t seem to be affected by the desperation of Clapton’s love for Boyd, only by how miraculous it was. (Clapton and Boyd eventually married.)

Phil Walden, who had managed Otis Redding up until his death in December of 1967, bought out Duane’s contract with Hall for $10,000. He wanted Duane to get a band together to anchor a new label, Capricorn Records. Walden, then only twenty-nine years old, had already been present for a few too many transmutations for his work as a businessman to feel purely serendipitous. He was engineering things, connecting loose wires: in 1962, when Walden was managing a young guitarist named Johnny Jenkins, he left Jenkins and Otis Redding alone in the Stax studio for forty-odd minutes. They recorded a single, “These Arms of Mine,” one of the sweetest, hungriest implorations ever put to tape: “These arms of mine / They are yearning, yearning from wanting you / And if you / Would let them hold you / Oh, how grateful I will be,” Redding sings. Jenkins plays a loping little guitar figure. The 45 eventually sold more than 800,000 copies.

Walden lined up a distribution deal with Atlantic while Duane teamed up with a drummer named Jaimoe (né Johnnie Lee Johnson); the guitarist Dickey Betts; another drummer, Butch Trucks; and the bassist Berry Oakley. He called up Gregg in Los Angeles, told him to get back east, fast. And in the spring of 1969, a six-piece Allman Brothers Band played their first gig, in Jacksonville, Florida, at a club called the Jacksonville Armory. Gregg had been home for just four days. Duane was wearing some kind of fringed vest onstage that night. There was a sense that something was happening.

Driving north from Tallahassee on Interstate 75, approaching Perry, Georgia, en route to Macon, I spotted a giant billboard featuring the word SECEDE, with LEAGUE OF THE SOUTH written below it in slightly smaller lettering. What it actually said was #SECEDE, the League of the South being, apparently, a Web-savvy operation. After I checked into my motor lodge, I carried a cold can of ginger ale and a nip of bourbon to the edge of the pool, arranged myself on a lounge chair, and opened my laptop.

The League of the South’s motto is “Survival, Well-Being, and Independence of the Southern People.” They are a radical neo-Confederate organization presently advocating, in 2015, for a second Southern secession, in which a sovereign South will be governed by a clump of “Anglo-Celtic” elites—men and women who “are not content to sit by and allow their land, liberty, and culture be destroyed by an alien regime and ideology.” It’s outlier extremism rooted in unapologetically racist notions. It is also the sort of dogma that is often and oddly associated with Southern rock, the genre that the Allman Brothers Band inadvertently founded in 1969, and which was quickly taken up by bands like Lynyrd Skynyrd, the Marshall Tucker Band, Molly Hatchet, and Charlie Daniels.

Few mythologies are quite as elaborate and enduring—as generous and as loathsome—as the folklore related to the American Southeast. All that kudzu and Gone with the Wind and sweet tea and endless anguished visionaries: it means something to people, casts a certain kind of spell. But those sorts of fascinations don’t often develop without something wretched very close.

Like most musical genres, Southern rock itself is strange to define—it is, at its simplest, a blues-based, r&b-influenced, heavily guitar-driven strain of rock music. But the related iconography is easy, familiar: Confederate flag, pickup truck, long, stringy hair, distaste for outsiders. What is particularly confounding about these associations—and they are so odious—is that Southern rock was built on interracial collaborations, and I don’t just mean in the expansive sense, in the way that all American popular music was in fact seeded by the blues, but in the actual sense, in that one of the founding members of the Allman Brothers, Jaimoe, is black. Duane and Gregg grew up listening to soul and r&b and blues records; Gregg has talked about pedaling his bicycle across the tracks—literally—to buy two-dollar LPs from a convenience store in a black neighborhood, toting home albums by B.B. King, Howlin’ Wolf, James Brown, Sonny Boy Williamson.

The band relocated to Macon in the spring of 1969. Walden, a Georgia native, wanted to establish Capricorn there and asked the band to come up from Florida. Since graduating from Mercer University in 1962, Walden had been booking or managing an impressive roster of r&b performers: Clarence Carter, Arthur Conley, Al Green, Percy Sledge, Jenkins, Redding. He had grown up in rural Georgia, and was taken, at an early age, with black musicians, whom he routinely booked for white parties. Capricorn was built on the notion of symbiosis, dissolving the membranes between genres, races, histories. “I think I quickly earned this reputation as this little white boy who loves black music,” Walden later told his niece, Jessica. “I was just infatuated by it. I didn’t listen to anything else. I sort of missed that whole Presley thing. To me, the greatest rock & roll singer of all time, and the one who still possesses the truest, purest rock & roll voice is Little Richard. That is where rock & roll is from. The white performers tapped into what marvelously talented black performers had created.”

Otis Redding’s sudden death via plane crash devastated Walden, knocked him out for a while. But now, working with Jerry Wexler, Frank Fenter, and his brother Alan, Walden was helping Capricorn Records find its legs, first as a series in conjunction with Atlantic and ATCO, and then as its own boutique enterprise. Capricorn would soon become synonymous with Southern rock—with the swampy, rollicking sound built in Macon.

The Allman Brothers Band moved into an apartment at 309 College Street, known more colloquially as the Hippie Crash Pad. The living room was lined with end-to-end mattresses. There was a Coke machine stocked with Pabst Blue Ribbon. The band members were taking all their meals at H&H Soul Food—Mama Louise Hudson, the chef and proprietor, was an early and inadvertent patron, feeding them on credit—and chasing each repast with fistfuls of psychedelic mushrooms.

Macon itself wasn’t sure what to make of all these goings-on. An interracial band of longhairs in the Deep South in the late 1960s—it was heavy. It had only been about thirteen months since Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis. Thirty-three school districts in Mississippi still hadn’t been desegregated. A gang of penurious bohemians palling around with a black man attracted notice, made people nervous. Nowadays, Sly and the Family Stone receives (and deserves) credit for being the first major integrated American rock band (and they were also multi-gender), but the Allman Brothers Band was right behind them. Gregg Allman spent his free time playing craps in the back of a black barbershop. They were, to borrow the parlance of the day, liberated.

Throughout their tenure, the Allmans remained loyal to the South, insisted upon it. The first time they played up north was in 1969, at a club called the Boston Tea Party. They were opening for the Velvet Underground for two nights, two sold-out crowds. It seems like an incongruous pairing, and by all accounts it was—this would’ve been “Pale Blue Eyes,” “Candy Says”–era Velvets, Lou Reed singing grim little couplets in his most subdued voice, with the kind of icy disaffection that comes so effortlessly to New Yorkers (and especially to Lou Reed). Imagine, for a second, that sound juxtaposed with Gregg’s warm, mischievous take on “One Way Out,” the Sonny Boy Williamson wailer the band had taken to covering. It’s a cagey song, but the live version the band recorded a couple years later—for 1972’s Eat a Peach—is one of the least cynical performances of anything, ever. And if they played it like that?

The band released its self-titled debut in late 1969. The album didn’t sell very well—around 33,000 copies. Butch Trucks later told the writer Alan Paul that they didn’t care much about sales, and especially didn’t care about changing, regardless of blowback from the industry. “They thought a bunch of Southern guys just standing there playing extended musical jams was absurd,” Trucks told Paul. “They wanted Gregg out from behind the organ, jumping around with a salami in his pants.”

The interior gatefold cover of The Allman Brothers Band features a grainy photograph of the band, naked, seated in a shaded woodland creek. Actually, Butch Trucks is standing up. He is wearing an exceptionally large hat. Berry Oakley’s coiffure is blocking his business, barely.

Gregg didn’t consider himself much of a singer, or not at first. I’ve come to find his performance on “Whipping Post” miraculous. It’s not a self-pitying song, but it is resigned: “My friends tell me / That I’ve been such a fool / I have to stand by and take it, baby / All for loving you,” he sings. It’s a song specifically about taking it—receiving the punch, absorbing all the blows you deserve and a whole bunch you probably don’t—but it is also about reckoning with the fallout of those wounds, with accepting how they linger. Sometimes, the song suggests, we are all wound. It becomes hard, in those moments, to find an unmangled part of yourself. That gruff, sprained-sounding baritone. It’s as if he were coerced into admitting his own sadness, like that moment a person sorta snaps, hollers: “Yes, I am upset.” He wrote the lyrics by rubbing burnt matches onto an ironing board cover in the middle of the night. “Good Lord, I feel like I’m dying.”

If you compare those vocals to the way he sings on, say, “Melissa,” from Eat a Peach, you can hear how he eventually learned to control and very nearly defang his voice. Somehow, between 1969 and 1972, he alleviated himself of something. Which is remarkable, considering that, by then, Gregg had lost both his brother and his father in horrifying, gruesome incidents. I like to think it was Duane who’d goaded him into singing the other way, yielding that strange fraternal muscle, the power brothers have over each other. Duane had made him give something up that he hadn’t wanted to, and now Gregg was taking it back, closing the vault. That earlier voice, it was for Duane alone.

By 1970, the Allmans had figured out they worked best as a live act: the music squirmed, needed air and room to wander. That year, the band released a follow-up LP, Idlewild South, and scheduled a 300-something-date tour. In a review of the album for Rolling Stone, the rock critic Ed Leimbacher said the Allmans were playing “briefer, tighter, less ‘heavy’ numbers this time around,” and compared them, several times, to Santana.

Idlewild South is, in its way, a more controlled record than their debut, but there is still a specific rowdiness to it, an elasticity. It is extraordinarily loose-limbed. To this day, “Midnight Rider,” a song Gregg cowrote with Kim Payne, one of the band’s roadies, feels like a kind of apotheosis of Southern rock—if not its precise genesis—in both spirit and form. All the elements are there, stacked up: Duane’s balmy, supple guitars, that insistent groove, those wary, get-me-out-of-here lyrics. The Allmans were a band preoccupied by motion. “The road goes on forever,” Gregg sings. “But I’m not gonna let ’em catch me, no.” Legend has it that Gregg and Payne broke into Capricorn Studios in the middle of the night to record a demo of the song. It’s like they had to grab it before it ran off.

Motion sustained and also undid the Allman Brothers Band. In 1971, when Duane was twenty-four years old, he crashed his Harley-Davidson Sportster while trying to avoid a flatbed lumber truck at the intersection of Hillcrest Avenue and Bartlett Street in Macon. He’d just left Linwood-Bryant Hospital in Buffalo, a rehab facility where he’d been attempting—alongside Berry Oakley and two of the band’s roadies, Payne and Red Dog Campbell—to kick a fairly robust heroin habit. According to Alan Paul, Gregg was scheduled to check in, too, but split at the last minute to white-knuckle it on his own.

Duane was alive when they put him in an ambulance but died a few hours later, in surgery. The Allman Brothers Band played at the funeral, with Duane’s guitar propped up where he used to stand. His friends placed talismans in the casket, provisions for the other side: a silver dollar, a throwing knife, two joints, a lighter, and his favorite ring, a silver snake that coiled around his finger and had two chunks of turquoise for eyes. He’s buried in Rose Hill Cemetery in Macon. The band used to hang out there, writing songs, getting stoned. When I visited the grave, just before dusk, it was cool, misty, verdant. There’s a fence up around it now, paid for by fans who grew concerned about the ongoing desecration of the site. Previously, bits of the tombstone had been stolen, defaced. According to local lore, people had often been caught engaging in sexual congress there. It’s also been said that a couple of particularly frenzied acolytes once dug a tunnel, trying to snatch the body.

There is a famous picture of Duane, taken earlier in 1971, performing at the Fillmore East. The band was playing the songs that would eventually comprise their breakthrough record, At Fillmore East, which had only been out for a little more than three months when Duane died (Rolling Stone called it “the finest live rock performance ever committed to vinyl”). He is wearing a long-sleeved henley shirt in an oceanic blue. The bottom button appears to be missing, revealing a triangle of rosy chest-flesh. His hair—shoulder-length, center-parted, and strawberry blond—is limp with sweat, clinging to his forehead like a pair of wet jeans. His eyes are squeezed shut and his mouth is ajar, gaped. His hands are on his guitar.

It is not the most flattering photograph, to be frank, although he made that face a lot, so it is also not anomalous. Something about his comportment here sort of resembles a catfish, glugging away at the bottom of a brackish pond. But there is another thing communicated in his expression, in the way his mouth is hanging open, as if it were unhinged at the jaw. It’s the kind of look you sometimes see on the faces of people undergoing a faith healing. It’s as if major things were coming in and going out.

“You get real wicked after somebody dies, and you get pissed off,” Gregg writes in his autobiography, My Cross to Bear. He reflects gently on the process of healing, of reorienting yourself around an absence: “It takes some time, and probably a few glasses of spirits.”

Interestingly, Duane’s death doesn’t take up too much space in Gregg’s book, which was published to acclaim in 2012. Gregg recognizes that grief changes shape, but it doesn’t leave you, or not really. There isn’t all that much to say about it after a while. “Not that I got over it—I still ain’t gotten over it,” he writes. “I don’t know what getting over it means, really.”

By all accounts, Berry Oakley changed after Duane’s accident. “The truth is that Berry Oakley’s life ended when my brother’s life did. Never have I seen a man collapse like that,” Gregg writes. Oakley started drinking like someone who did not much care for being alive: a case of beer every morning, early. A bottle of Jack Daniel’s by mid-afternoon. He was often too fucked up to play bass. A year after Duane’s death, Oakley drove his own motorcycle into the side of a bus three blocks away from the crash site. Some people think he did it on purpose. He was wasted. He refused to get into an ambulance. He went back to the house and sat around and had a brain hemorrhage and died.

The band released Eat a Peach, its third studio record, in the winter of 1972. It was gold by the time it shipped and debuted on the Billboard Top 10. Dickey Betts capably plays what would have been Duane’s parts. The album opens with one of my favorite Allman Brothers songs, “Ain’t Wastin’ Time No More,” which Gregg wrote on a one-hundred-ten-year-old Steinway piano, and which features this lovely little vocal move on the chorus, where Gregg sings “Time goes by like hurricanes / And faster things,” only he makes the words rhyme, lets them extend and dissipate, lets them disappear elegantly, like smoke rings in the night. It barely happens, but you notice it.

Oakley, who was alive for most of the recording, was not alive for the accolades, or the influx of cash. Phil Walden started piloting a white 1965 Silver Cloud Rolls-Royce around Macon. Capricorn was taking off. Soon they’d be releasing records by Marshall Tucker, James Montgomery, Elvin Bishop, Bobby Whitlock. The band toured and toured. The Allmans released a follow-up, Brothers and Sisters, in the summer of 1973. The record made it to No. 1 on the pop chart, due in part to the success of “Ramblin’ Man,” a major-key paean to eschewing responsibility (it was written by Betts, and inspired by the Hank Williams jam of the same name).

“Ramblin’ Man” enjoyed a long and somewhat curious stint as an AM radio hit, a small coup for a rock band in the early 1970s. It’s a buoyant, carefree song, the kind of thing that sounds good at a cookout while you are squirting mustard onto a hot dog, but terrible later on, in your bedroom. The band started jetting around on a customized Boeing 720B—the same plane commandeered by Led Zeppelin and the Stones—and doing spectacular amounts of drugs. (They were briefly joined on that tour by an adolescent Rolling Stone reporter named Cameron Crowe, who later mined their road shenanigans for both a magazine story and his film Almost Famous.)

They made a bunch of shitty records after that. Gregg started dating Cher (“I’m sorry, but she’s not a very good singer,” he later wrote of the union). There were a lot of mediocre side projects. By the late 1970s, the band was done. Animosity was high; people were broke, paranoid. Walden himself was becoming an increasingly contentious figure in the manner of all great rock managers and impresarios, like anyone who ends up with a mercenary stake in the production and dissemination of an art that is not entirely his own. His legacy is still regarded with equal parts wariness and reverence (he died, in 2006, of cancer). He is often credited, fairly or not, with helping Jimmy Carter get elected president in 1976, throwing the full Southern rock gentry behind Carter’s bid, hosting benefits, concerts, events. Eventually, it was revealed that Phil Walden owed a lot of people a lot of money. Capricorn went bankrupt.

In 2014, the old Capricorn Records building was decreed uninhabitable by the city of Macon, although it somehow avoided timely demolition. The whole block has recently been purchased and the community apparently has designs on rehabilitation, on turning the space into a new set of lofts or offices. Otis Redding set up business there in the late 1960s—you can see the exterior of the building in the video for “Tramp,” the one where he’s wearing that terrific green suit and counting cash on the street. For now, the building’s concealed behind a temporary black wall. From afar, the barrier looks like one of those opaque bands blocking out sex organs on the covers of nudie magazines. If you stand close enough and sort of jump up and down in front of it—or, emboldened, perhaps you attempt to scale it, maybe getting yourself close enough to the top to snap a cell phone photo, one eye on the sheriff’s car idling across the street—you can still make out where the old letters hung, the ones that spelled out CAPRICORN. After my visit, I drove to a bar downtown, ordered a bourbon and soda, and listened, no joke, to “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” on the house stereo. I thought about what had been made there, in Macon.

I still don’t know how to write about this without sounding hysterical, but there’s something in those early records that seems to presage tragedy. I keep listening for it now, trying to parse it out, name it: certain things run so hot that dissolution of a sort seems inevitable. All the great loves work that way. It’s so present in Duane’s guitar playing—a flood, like the valves were too open, like too much of him was getting in. And his bandmates, his little brother: how do you lose like that and keep going? And not only keep going, but thrive, find a way to make songs that are joyful, exultant?

It’s hard, these days, in Macon, to feel the sense of possibility that must have been present there in the late 1960s—a belief that the future might transcend the past, that, as Lou Reed sang, “what comes is better than what came before.” The Allmans found it, and held it, at least for a short while.

The band eventually got back together, in the eighties. In the 1990s, they released a string of fair-to-unremarkable albums. They played some shows that were considered epic—perfect—and only officially retired from the road in late 2014. The jam-band preoccupation of the early 1990s had helped them commercially. Young people suddenly had stamina for noodling. Personally, I recall some of those shows feeling downright transcendent. They’d put off the studio years before that, although they were never really a studio band to begin with. Their music lived in the air, in that Florida-Georgia haze. You had to feel it on your skin.

“Midnight Rider” by the Allman Brothers Band appears on the Georgia Music issue CD

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.