Hammer in Her Hand

By Rachael Maddux

Beverly “Guitar” Watkins is seventy-six years old. She is wearing house slippers, a hair net, and an Atlanta Hawks t-shirt on backwards. She is probably the greatest living blues guitarist that no one has ever heard of. Today, she is trying to sell her couch. “This couch is nice,” she says. Watkins stoops and smacks the button that makes part of it lean and a footrest pop out. “It does that on both sides. It cost four hundred dollars. My son picked it out for me. I’m selling it for two hundred.”

She is trying to sell her couch because she wants to move out of this apartment on the third floor of a seniors-only complex in Atlanta’s Old Fourth Ward neighborhood. Down in the lobby, a gaggle of women her age sit propped up in wheelchairs, their faces lit by daytime TV. Hidden speakers pipe an endless playlist of schmaltzy pop standards into every hallway and common room. It’s a nice enough place, but it’s not her scene.

“I want to be where I can be free,” she says. “I live that rock & roll lifestyle.”

Watkins learned to play guitar as a child and began playing professionally while still in high school. In the 1960s, she played on recordings that inspired a generation of white rock & rollers, toured with bands across North America and Europe, opened for Ray Charles and James Brown and B.B. King. She caught the early wave of soul music, crashed on the sandbar of disco, brushed herself off, and kept on going. She reinvented herself as a solo artist at fifty, recorded her first album at sixty, survived multiple brushes with death, and did it all almost completely without celebration, peer, or precedent.

And she’s still doing it. Last Thursday she played her regular gig at Blind Willie’s over in Virginia-Highland. Yesterday she spent all day at one of the two churches where she worships and performs every month. Tuesday she’s playing a memorial birthday party for her cousin Freddie, who died last year. Saturday, the Fourth of July, she’s playing a kids’ soccer game. Sunday afternoon, she and the Meter-Tones, one of her several backing bands, will play to travelers in the atrium of the Atlanta airport. On her days off, she rehearses. Watkins credits her talents to God.

But if God made her good, she made herself great.

Watkins’s phone rings. On the other end is Rob Baskerville, the leader of another one of her backing bands, the King Bees. He’s calling about their upcoming performance at a music festival in Minnesota. There’s the issue of promotion. Watkins’s website and Facebook page haven’t been updated in a while—the most recent post is about her seventy-fourth birthday celebration at Atlanta’s Northside Tavern two Aprils ago. Given her age, the silence raises some questions. “That’s gotta be done,” she tells Baskerville. “The people don’t know if I’m dead or alive!”

Beverly Watkins was born in 1939. Her mother died when she was three months old, so she was raised by her grandparents and her mother’s sisters—first in Atlanta, then out in rural Commerce, Georgia, then back in Atlanta. Her grandfather was a sharecropper and played banjo at barn dances. Her aunts Margaret, Bea, and Nell sang in a group called the Hayes Sisters that traveled around, performing at local churches and parties. The voices of Marie Knight and Sister Rosetta Tharpe lived inside the horn of her grandmother’s Victrola. Young Beverly was a mimic, singing and plucking on thin air.

Watkins was eight when her aunt Nell bought her a guitar from the Sears-Roebuck catalog, a child-sized Stella. The first song she taught herself to play was “John Henry.” In high school, she won a talent show playing “Blue Suede Shoes” on that tiny Stella, in the rough, finger-picked style she still employs. By then she’d picked up piano and bass and trumpet, and her school’s bandmaster had noticed her talent. “When he ordered the instruments for the school, he ordered a guitar,” she says—electric, full-sized. “He turned me all the way around.”

The bandmaster got Watkins to play in standard tuning, and then things started happening fast. She’d already been playing bass with a local band called Billy West Stone and the Down Beats. Next she got an audition with Piano Red, a black albino barrelhouse bluesman who’d been playing and recording throughout the South since before Watkins was born. He’d had a few national hits in the early fifties (“Rockin’ with Red,” “Red’s Boogie”) and was looking to tour with some younger folks. During her senior year of high school, Watkins was drafted into his new act as one of three rhythm guitarists.

Dr. Feelgood and the Interns started out playing at clubs and colleges around Atlanta and eventually went national. They signed to Okeh Records, a division of Columbia, and recorded what would become Piano Red’s final hits: “Doctor Feel-Good” and “Right String but the Wrong Yo-Yo,” a remake of one of his earlier songs. The B-side to 1961’s “Doctor Feel-Good” was a song called “Mister Moonlight,” written and sung by Roy Lee Johnson, another one of the band’s guitarists. The single found favor among young blues-gobbling white musicians, especially in the U.K. Johnny Kidd & the Pirates recorded a cover of “Doctor Feel-Good,” and the Merseybeats, the Hollies, and the Beatles all covered “Mister Moonlight.”

The tours were exhausting, and not just because of their schedules. The mid-1960s was a tricky time for a group of black kids to be traveling around America. The band was often booked to play in hotels that didn’t allow black guests. In some cities, the group would send Piano Red into a restaurant to order food for the whole band—his pigmentless skin allowed him to pass as, if not white, then at least not black.

As a young black woman, Watkins was in a doubly tricky spot. Sometimes Piano Red’s niece Zelda came on tour to keep her company, but otherwise she was the only woman around, in the van and onstage. (The male Interns wore white doctors’ coats when they played; she wore a nurse’s uniform and hat.) “Piano Red was just like my dad,” she says, “and they was like my brothers, all the band members back then. Piano Red said, ‘If you all go out anywhere, make sure you take care of Beverly.’ And they did. I was very attractive. If somebody would walk up to me, want to talk to me, I’d say, ‘Oh yeah, that’s my husband right there’—I’d pick somebody in the band.” At twenty-four she got pregnant, gave birth to a son, and kept on touring.

Watkins was an instrumentalist, not a singer, which made her even more of an oddity. The images of black men playing guitar and black women cradling a microphone long ago became our ubiquitous hieroglyphs of the blues, and even now the image of a black woman playing guitar still registers as something crackling and new. It’s not that Watkins had no one to look to as she was coming up—in the thirties and forties there had been Sister Rosetta Tharpe and Memphis Minnie; in the fifties and sixties, Peggy Jones was performing as Lady Bo in Bo Diddley’s band and Odetta was modestly popular on the folk scene. But the path cut before her by these women was faint, and mostly uphill.

Not that Watkins needed a path. The greats rarely do. In the first verse of “John Henry,” the steel-driving man is just a baby with a hammer in his hand, singing, “Hammer’s gonna be the death of me.” As John Henry was always John Henry, Beverly Watkins was always Beverly Watkins. Sometimes fate just makes itself known.

Piano Red changed the name of his band a few times—Dr. Feelgood and the Interns, Piano Red and the Houserockers—before the act dissolved in 1969 (he died of cancer in 1985). By 1970, Watkins had joined up with Leroy Redding, cousin of Otis, and was playing in his band, also called the Houserockers. She played for a few other groups, with musicians she loved and admired, but the work wasn’t what it used to be. Soul and r&b begat disco, and many of the first white rock bands to feed on the output of black American blues artists had given way to their own imitators. There was even a white British rock band called Dr. Feelgood, named after the Johnny Kidd & the Pirates’ cover. (They’re still touring; their website calls “Dr. Feelgood” a “blues standard” and makes no mention of Piano Red.)

Watkins had spent half her life in bands that helped build a world that now had no place for her. She returned to Atlanta and started looking for work offstage. She worked at a car wash, cleaned houses, cleaned offices. But she never stopped playing music.

Piano Red had spent ten years as the house musician at Muhlenbrink’s Saloon in Underground Atlanta, a downtown retail district that closed in 1980. When it opened again in 1989, Watkins installed herself as the unofficial house musician of the food court, playing for tips. Billing herself as Mama Watkins, she played blues standards and oldies, sometimes with a drummer and her son on bass, other times with just her guitar and a drum machine. She started singing, too. She’d learned a certain kind of showmanship from her years with Piano Red—the matching outfits and the dance moves he demanded of his bands, his cheerful rapport with the audience—and now she was developing her own style. She’d goose-step like James Brown, sling her guitar around her neck and play a crackling solo behind her head, then hold a note and drop down into a half-split on the concrete. She didn’t make much, sometimes just forty dollars a night, but she couldn’t afford to be discouraged. A friend told her she needed a catchier name if she ever wanted to make a record. It seemed like a distant prospect, but she became Beverly “Guitar” Watkins anyway. Just in case.

In 1990, Watkins started showing up at Fat Matt’s Rib Shack, a barbecue joint with a Wednesday night jam session that had become a haven for Atlanta’s older blues musicians. The usual crowd included her former bandmate Eddie Tigner, singer Cora Mae Bryant, and one-armed harmonica player Neal Pattman, each trying to figure out how to stay alive and keep making music in a world unconcerned with whether or not they accomplished either. Also among the regulars was a twenty-five-year-old white kid from Savannah named Danny Dudeck, a singer and slide guitarist who’d just begun to perform blues under the name Mudcat.

Dudeck was taken with Watkins from note one. On Wednesday nights he’d watch through Fat Matt’s big front window for her to arrive, then sidle up to the stage, hoping for a chance to play with her. “It just seemed obvious,” he says. “You go to the deepest well to find the strongest stuff.”

Over the next few years, as he built his own career, Dudeck helped book Watkins at Northside Tavern on Atlanta’s industrial Westside, took her to Paris for her first international solo gig, and brought her along to play blues festivals all over the South. He did the same for Tigner and Bryant and Pattman and others, too, and his work caught the attention of a man named Tim Duffy. In 1994, Duffy founded the Music Maker Relief Foundation, in North Carolina, to help unsupported artists—usually black, elderly, and financially vulnerable—land record contracts, studio time, and live bookings. He asked Dudeck for names and Dudeck told him about Watkins. The next time Duffy came through Atlanta, he stopped downtown to hear her play.

“It was just her and an electric guitar with no rhythm track—nothing, just her,” Duffy says. “And then she started hitting a note and going with it and grabbing it and feeling it to her chest and dropping to her knees and playing it behind the head. A lot of musicians that solo, I would call it a ‘look at me, look at me, look at me’ lick—but Watkins was playing the blues from the center of her heart and it was just there for everyone to enjoy. I was transfixed. Ever since that, just thinking about it, I can hear the guitar solo in my head.”

He put fifty dollars in her tip bucket. Watkins remembers it: “He said, ‘Beverly, I want to help you.’ He said, ‘I’m gonna see if I can get you a recording contract.’ I said, ‘Okay, alright.’”

A few months later, Watkins was recording with Mike Vernon, the British musician and record executive who’d produced records by early David Bowie, Fleetwood Mac, and Eric Clapton. (He’d also produced the 1979 album by the other Dr. Feelgood.) In 1999, Music Maker released Watkins’s first record, Back in Business. She was sixty years old.

With Music Maker behind her, doors began to open where only walls had been before. For two years, Watkins traveled around the U.S. with blues multi-instrumentalist Taj Mahal on the Winston Blues Revival, a massive tour sponsored by the cigarette company. She was one of a few supporting acts until, one night, Mahal switched their billing, telling the crowd, “Don’t leave—you’re in for something!” Dudeck, who played in Watkins’s band on the tour, remembers watching the crowd watch her—the dropped jaws, the tears on the faces, the crowd of hundreds having the same reaction he’d had twenty years ago at Fat Matt’s, the same reaction Tim Duffy had watching her in an empty food court at Underground Atlanta. “It’s in her hands,” Dudeck says. “When you hear that one note, people turn their heads, your jaw drops. You can write poetry about it, but you can’t really say why it was so important. She does that.”

Music Maker helped Watkins release her second album, The Feelings of Beverly “Guitar” Watkins, in 2005. Around the same time, she got sick after a show in Washington, D.C., and made it to the hospital just before one of her heart valves clenched shut. While she was in the hospital, recovering from the heart attack, doctors found a mass on the upper lobe of her left lung. To get the cancer out they had to slice down her left side, leaving a scar like a shark bite. For months she couldn’t raise her arm high enough to hold her guitar, let alone hoist it over her head. It was a year before she could work again, two before she was able to do her signature trick.

Now her skills are sharper than ever. She still takes lessons, still learns new licks and chords, and she still holds her bands to the same high standards she’s always had: “Back in ‘em days when I came up, I had to practice,” she says. “If we were late for practice twice, I mean, the next time you didn’t play. That’s the way it was when I was in Piano Red’s band. My band now, they have to be on time. And we practice. And we sound good.”

This is what she means when she says she lives “that rock & roll lifestyle.” She can’t rehearse with a band at her apartment at the seniors-only complex. She wants to be somewhere she can spread out, maybe even somewhere with a yard (she wants to grow some tomatoes and peanuts and collards). But before she moves, she wants to make another gospel album (her first was 2009’s The Spiritual Expressions of Beverly “Guitar” Watkins) and then another blues record. All this on top of the gigs at Blind Willie’s and Fat Matt’s and Northside and all the soccer games and birthday parties and airport terminals in between.

Last December, an aneurysm left Watkins carrying a stent in her brain and wearing thick, prismed glasses to correct her vision. After years of straining to sing into poorly engineered sound systems, her vocal chords are in rough shape, too. But she’s waited, and worked, a lifetime for this. Music is the only sort of future she ever imagined for herself, even when it was all but unimaginable. Now she lives it every day.

“I did want to go to the Air Force,” she says. “They came to my house when I was a senior and I took the test, but I flunked the vocabulary test. I didn’t know I could have volunteered and went on in the Army and played in the band. But I don’t reckon that is what the Lord wanted me to do. So here I am, from there to here I am, and I’m still rolling.”

In late August, Mudcat booked a gig at Northside Tavern, with the Atlanta Horns, and invited Watkins to play as his special guest. Northside is a lone grimy holdout on Atlanta’s gentrified Westside. As the old industrial buildings get turned into condos and upscale retail shops and restaurants with staff mixologists, the squat little concrete-block building remains as it’s always been, smoky and neon with revelers overflowing into the parking lots on Saturday nights.

Dudeck and the band started the show with a second-line performance of “When the Saints Go Marching In,” blaring brass and washboard and banjo, weaving through the packed room. Watkins brought up the rear, wearing a navy pantsuit and blowing kisses to the crowd. During Mudcat’s set, she sat in the back, next to the merchandise table, sipping from a giant coffee mug. To anyone who didn’t know better, she must have looked out of place—not that anyone’s attention was anywhere but the stage, or the dance floor down in front, where the college kids and the recently ex-college kids and the middle-aged bachelorettes danced and grinned in the sweaty cigarette haze.

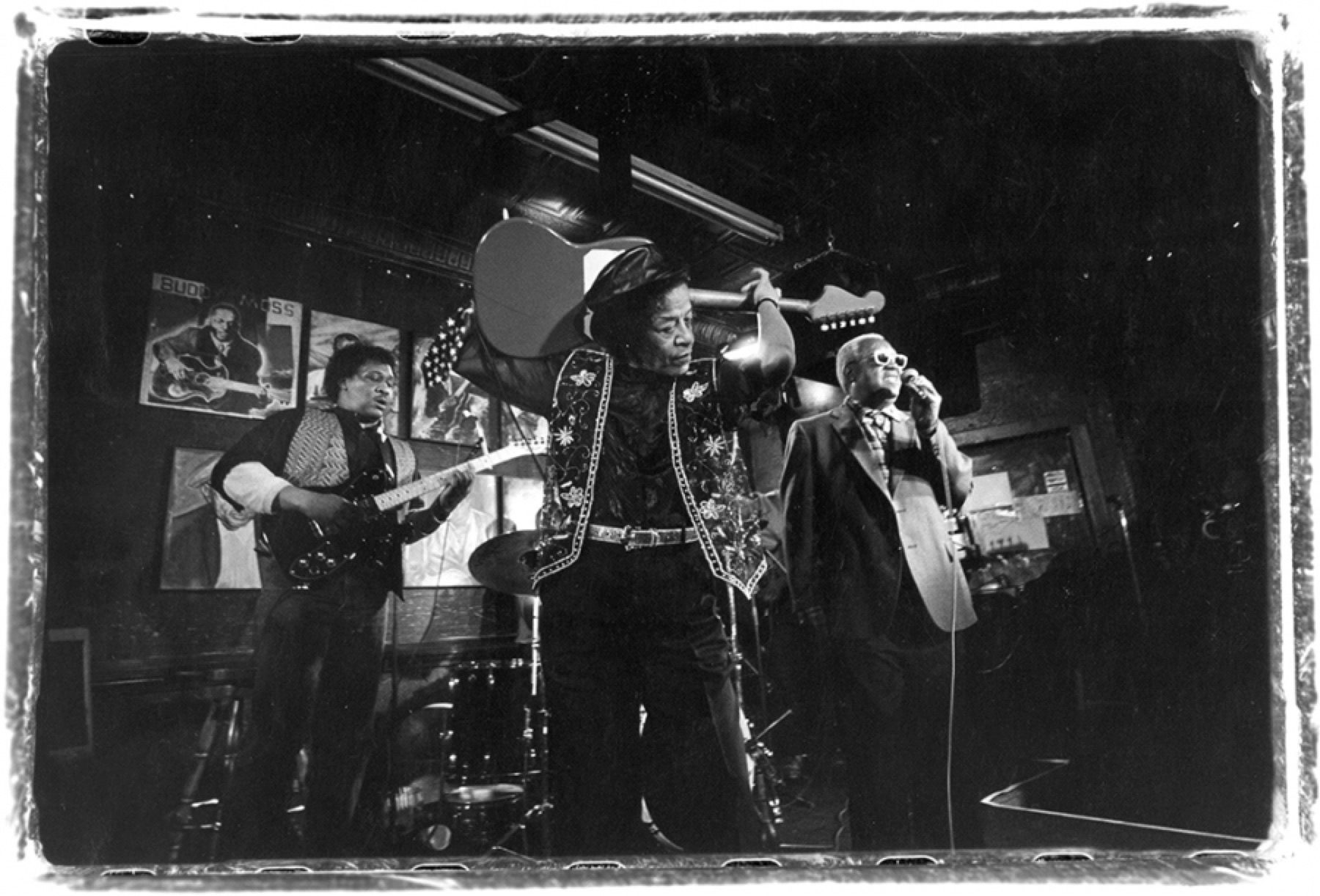

After a while, Dudeck stepped back from the mic and trombonist Lil’ Joe Burton came forward. He spoke through the crackling din of the crowd: “Ladies and gentlemen . . . Atlanta blues legend . . . ten-year cancer survivor . . . we call her Mama Watkins . . . you call her . . . Beverly ‘Guitar’ Watkins!”

Watkins floated to the stage, hopped up, grabbed her black-and-white Fender Stratocaster, and welcomed the crowd with a big hello just like Piano Red taught her. The band fell in beat right behind her, pummeling through “Back in Business” and covers of “My Girl” and “Shake, Rattle and Roll” and Watkins’s own version of “Wrong Yo-Yo.” An older woman in a sparkly poncho twirled and twisted and swung her hips like she wasn’t also holding a fold-up walking cane. A cluster of white dudes in polo shirts took turns doing a dance that involved doffing a straw sombrero. An extremely tall black man stood in the middle of the crowd, recording video of the band with his iPhone, his face slack with awe.

That night at Northside, Watkins was indulgent, profligate. Every time she hoisted the guitar above her head, the wild crowd went wilder. And every time, she grinned under the weight of it, never missing a measure, never slowing down. A body in motion stays in motion, and she’s been on the move for years. What she’s in search of is not a place she could rent, not a place to stick a couch. All she really needs is space enough for a small woman and a big guitar and the crowd that always follows. It’s here she’s most at home—onstage, in the thick of it, hammer in her hand. At home, and very much alive.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.