The G.R.I.E.F.

By Micah Stack

“Pleurant, je voyais de l’or—et ne pus boire.”

—Arthur Rimbaud

Full disclosure up front: I am a gay black man, a proud New Orleanian, thirty years old, five out of the closet, a decade on the down-low before that; bi-dialectal as every educated brother in this city must be, a code-switcher as needed; a poet in my spare time, in my unspare time a poetry teacher devoted to dead French guys and live black ones. Like most black men of my generation, I belong to the hip-hop nation, and like any sensible gay man, I’m ashamed at times to say I’m a fan. The homophobia, the drug dealing and gun toting, the bling and the misogyny—it can feel like stylized, repetitive ugliness, at least mainstream gangsta shit. But I’m an addict, hooked on one rapper above the rest: Mr. Stillz. I’ve memorized hundreds of his verses, seen the documentaries, the interviews, the countless clips of him recording in his psychedelic freestyle mode. I subscribe to the hip-hop mags because he decorates their pages. So naturally my theories ran buck-wild when the photograph surfaced.

First, though, the facts: On February 12, 2008, two days after Stillz racks up six Grammys, it appears online. It must’ve been snapped just after Katrina, judging by Stillz’s incipient dreads, the fleur-de-lis tattoo under his right sideburn, and the absence of The G.R.I.E.F. inked across his right temple (you can timeline his life by his tats). Diminutive Stillz and muscled-up Wreckless Tyrone embrace in a handshake/hug combo. They’re French kissing. They both wear white—Stillz in a wife-beater, Tyrone in a tracksuit—and there’s a patch of shine on Tyrone’s always-Michael-Jordan-clean dome. They’re under a pavilion, bright palm trees rising beyond its white columns. Bodyguards and hangers-on surround them. Some look away, but two meaty goons mean-mug, disgusted by this display.

Hours after the pic’s gone viral, a super-high Stillz gives an interview on his tour bus. He says, Hell yeah I kiss Tyrone. That man raised me and believed in me when I ain’t had shit. It’s just a form of affection. It’s all love.

I imagine him when he realizes what he’s done. Back on his tour bus heading to Miami, he glues himself to his laptop. Tyrone’s riding a different bus now: can’t stand to see Stillz so slurry from the sizzurp. In web searches, the photo is always—already—the first image to appear. Parodies have flooded YouTube within hours. Rappers he’s collaborated with are calling him a faggot. Two days ago he conquered the world and now he’s here torturing himself with YouTube comments about how fake he is, how soft, how they shoulda known that any nigga who wore that much pink just had to be sweeter than a pancake. Every entry, each little drive-by of hatred, makes it harder for him to breathe:

doughboy187 (Just now)

mr stillz a great raper but he sucking tyrone dick lol

MySwagSoOfficial (Just now)

i like somr of mr stillzes muzik but i worry about him he a lil fruity ;-)

kumquill (1 minute ago)

A skr8 ^ pussy with NO musical talent whatsoever.

And dozens way worse than that. He tells the driver to stop the convoy. He storms onto Tyrone’s bus. Everybody get the fuck out, he says, and pushes Tyrone into the bedroom. He pulls a .40 cal from his knapsack, presses it into Tyrone’s neck and says, Who leaked the picture? Who leaked it? I will kill a motherfucker dead, you heard me?

Put the heat down, Stizzle, damn.

Was it Splack? Splack leak the picture?

Junior, Splack in jail. Now put the toast away.

Stillz lowers the pistol. Tyrone grabs it and stashes it under the mattress. He’s used to Stillz wildin out like this. Back when he first discovered the kid, when he was still Ahmad Trench—even then he could flip like a light switch. Tyrone sees both the boy from back in the day and the man standing in front of him: they oscillate in his eyes like a hologram. He wraps the man in his arms, rests his chin on thick ropes of hair that smell like cologne and great weed. Had he harmed the kid by giving in to his urges? Stillz always initiated, but maybe Tyrone should’ve been stronger. For a long time he stays there, holding Stillz.

Junior, don’t trip on what them haters say . . . they don’t understand a damn thing.

Stillz yanks himself loose. You see what they writing about us? About me?

Better watch the way you acting, Tyrone warns.

Nah, I ain’t got to watch nothing. I’m on that Casper tip now, Paw: I’m ghost.

And he swaggers off the bus, leaving Wreckless Records—and Wreckless Tyrone—behind.

He announces he wants out of his contract. He sues Tyrone Mosely, his surrogate father and the founder/CEO of Wreckless Records, his home since age thirteen, claiming “fiduciary misconduct and unjust enrichment.” With the case tied up in court, he spends months holed up in his Miami mansion. He has women, weed, and pint after pint of promethazine/codeine syrup delivered to him. Buys Lambos and Bugattis he’s always too high to drive and keeps grinding out the mixtapes that made him famous, releasing them for free online. He raps till sunrise, when he falls asleep in the private cinema adjacent to his studio, curled up on the couch, shaking.

We have to rewind the track. Summer of ‘95, New Orleans: Wreckless Tyrone sits in his Mid-City office. The A/C’s blasting. With his feet up on the roll-top desk, he rubs a Cohiba along his top lip, contemplating how far he’s gotten in the rap game and how much farther he can take it. He’s got swagger for weeks but he’s real with himself: he lacks the mic skills to be a truly great rapper. His breakout single, “Shine Like Me, Bitch?” is tearing up clubs in the city, but its popularity probably owes more to the “Triggaman” beat he jacked from DJ Jimi than it does to Tyrone’s flow. Splack Diggity’s rhymes are tighter; his soldier style (gold teeth, fatigues) and his catchphrase (“You heard me!”) are catching on in the streets. But Tyrone’s not sure Splack can take Wreckless Records to that other level. Fuck being local news, he thinks: it’s time for 60 Minutes. The cigar smells raw and sweet, like burnt sugarcane. His label’s office/studio is on South Claiborne in the same hood where he used to move weight. Definitely time for an upgrade.

He picks up the phone and dials Wild Wayne at Q93. Wayne hosts the 9 O’Clock Props, where aspiring rappers call in and rhyme over classic New Orleans bounce beats. He gives rookies the first test: Hey, you, what’s your name? / It’s the 9 O’Clock Props witcha boy Wild Wayne! Callers rhyme about themselves. If the flow is wack they get the toilet-flush sound, but those who spit fire proceed to the next challenge: The 9 O’Clock Props is on / Tell me where you calling from! Then they describe their hoods. For Tyrone’s dollar, nobody could flow like the Trench Sweeper.

It’s ya boy Wild Wayne, what’s really good?

Anybody who rhymes on the Props can give the Q permission to share their info with labels, so Tyrone asks Wild Wayne where the Trench Sweeper calls from. Wayne hunts through his files, says Ahmad Trench stays at 808 Congress Street, in the Upper Ninth Ward. They chitter-chat for a minute, then Tyrone says, One love, and hangs up. He finally puts a flame to the cigar. Getting the bitch lit takes forever, but when he blows out the first cloud, he’s bathed in satisfaction. He’ll take the new whip for a ride to the Ninth. After he smokes the Cohiba.

He’s got the bass rumbling hard in the Bentley, beating up the block like King Kong is in the trunk. When he sees the Keep It Real Barbershop on the corner, he busts a right onto Congress. On the stoop in front of 808 he spots a short, wiry kid with fucked-up cornrows wearing a baggy t-shirt and blue Dickies, a pair of ragged-ass Chucks on his feet. From Tyrone’s ride it seems like the whole block is shaking. Heat rises from the pavement and makes wavy lines in the air like a desert mirage or some shit. He kills the engine and the street stands still.

You the Trench Sweeper?

Maybe. What you know about me?

You know who I am?

Yeah, I know Wreckless Records. “Who Started That Fire?” was cold-blooded.

Tyrone gets out and leans against the Trench Sweeper’s stoop. He says, You feeling my man Splack Diggity, huh bra? Well Splack say you got that fire—heard you on the Props with Wild Weezle. He told me the other day, Roni, we need to go Batman on this industry. You know why Batman was the shit?

Because dude was mad rich.

Nah . . . I mean, that’s true, but: Batman was the shit because the nigga had Robin.

I always thought Robin was a little bitch.

You know how it feel to have ten Gs in one pocket?

Not yet.

Good answer. If you come correct, you’ll see what it’s like to have your pockets on steroids. Now bust me some rhymes, right off the dome.

The Trench Sweeper raps about what’s around him—Tyrone’s rims spinning like rotisserie chickens, his grandmama’s stoop where he’s trying to make a living. The bike he pedals on, the crack he’s peddle-ing; he can’t stand being broke, so he’ll fall for better things. He is a hustler—he’d rather die than to live average, even if he got to live savage. He was born to eat rappers like they came from McDonald’s, then he hollers Rest in Peace to his mama and Ronald.

Tyrone pulls a G-stack from his pocket and tosses it at the kid. If he cleans him up, calls some broads to hook up his hair, gets him some fresh gear, the Trench Sweeper might just be the ticket to that other level. A teenage gangsta rapper, not one of these little-kid fad groups but a straight-up G that nevertheless would make females want to pinch his cheeks. Splack should’ve came, but there would be time for that, time to put them together in the studio and make gold like Midas.

Tyrone is a shrewd-ass businessman. He must have figured out quick, when he heard Ahmad’s story, that the kid was more likely to become Batman than Robin. See, the year before the discovery, when Ahmad was twelve, he watched his mama and her boyfriend Ronald Beemon get killed in a drive-by. They could build a Batman-type myth out of that and ride on it till the wheels fall off.

But it isn’t just shrewdness. Tyrone legally adopts Ahmad, raises him like his own son. He watches with a father’s pride as the Trench Sweeper transforms into Mr. Stillz, one half of the Tech Toters and (temporarily) the Robin to Splack’s Batman. As the Tech Toters’ first album, We Started That Fire, goes gold; as Wreckless Records goes nationwide and the Tech Toters graduate from gold to platinum; as Splack Diggity is convicted on gun charges and Stillz goes solo, Tyrone’s pride in his son keeps swelling. He loves Ahmad Trench more than his own children.

Mr. Stillz becomes a daddy himself while the Tech Toters are promoting Flame Gang Soldiers, just before Splack gets sent to the pen. Tyrone throws a party at a hip-hop hotspot in the NYC meatpacking district. There’s video footage. Hollywood starlets flirting with Harlem hoods. A life-size ice sculpture of Stillz sparkling by the bar. Cases of Cristal. They shake up bottles and spray Stillz like he’s just won the Super Bowl. Tyrone has the waiters wheel out a three-tiered cake with red and yellow icing, the old-school Atlanta Hawks colors that the Tech Toters made their signature. Around the cake’s base is a platinum chain with a cross full of flame-colored diamonds.

Father and son embrace beneath a confusion of flashbulbs and clapping. Stillz licks smudges of icing off the chain and drapes it around his neck. Splack gives him a hug but then turns away, mean-mugging. He’s starting to act like a hater lately, Stillz thinks, even though Splack knows males shouldn’t be jealous—that’s a female’s trait. Their new single shakes the speakers. Tyrone says he’ll be right back. More people pour in, girls grinding and twerking on the dance floor, the whole room swirling with sensation: weed smoke wobbling on the strobe-lit air, the poof! of a popped bottle, a sailing cork. With a broad on each arm and a bottle in both hands, Tyrone crosses the room hollering, Show em your chain, Junior! Stillz flashes his huge smile and holds up the glittering cross. Tyrone brings over the two girls, both Blackanese, and puts his mouth by Stillz’s ear. That Jesus piece is fly, he says, but I got your real gift right here.

The quartet retreats to a private suite. No footage of that, but certainly that’s when it started. And it probably only happened that way, the it-ain’t-gay-if-it’s-in-a-four-way way, until the storm destroyed 2005.

Tyrone drives the Phantom, Stillz riding shotgun, bodyguards stuffed in the back like prisoners. At the Elysian Fields exit they show their licenses to the National Guardsmen, who tell them to inspect their property and complete their “revacuation.” They descend into the city. The road is just a pause in the rubble, and through bloodshot eyes Stillz watches the ruins crawl past: broken ukuleles, Mardi Gras beads, tiny football helmets, boards scattered like hacked-off arms, street signs flipped around or blown off. Flood stains on house-fronts remind him of the notches his mama carved on the wall every year to see how grown he was getting. On a warehouse somebody has spray-painted HOPE IS NOT A PLAN. Stillz points and says, That’s the realest shit I’ll ever quote.

They ride on. They pass telephone poles cracked at the waist, houses leaning like three-legged lions, a refrigerator sitting in an oak tree. It’s quiet for a good minute until one of the bodyguards says, God damn. Then it gets quiet again. The city smells like God took a shit on a heap of cotton candy.

Ain’t that where Splack used to stay? Stillz says.

Tyrone says, That was his mama’s house.

I wonder where she at now.

I ain’t found her yet. I’ma throw a couple hunned thousand at her when I find her.

If you find her.

Don’t be talking like that, Tyrone says.

Man, this here’s a war zone, says Stillz. Ain’t no point to being optimistic.

Still, he somehow hopes he’ll find 730 Flood Street untouched. First they drive past 808 Congress, where Ahmad had lived with his grandmama that one year. She lost both feet to diabetes in 2003; shortly after that she stopped breathing. Stillz didn’t come off tour to see her—that still fucks with him when he lets himself remember. Tyrone’s all the family he got left now, and he ain’t even kin. But Tyrone is more family than his kin ever was any damn way. Except for his mama: that was his heart. Even though she was already gone, he fixed the house up how she had wanted it. He needs to find it that way.

They cross the bridge into the Lower Ninth. He hasn’t touched down in forever: it’s like seeing it in a dream. Tyrone steers around a corner and Stillz tells him to pull over at the playground. He gets out, rests his hands on the links of the fence that is, amazingly, still standing. Tyrone joins him. The bodyguards mill around, looking like second-string linemen. Off in the distance some brother is on the roof playing trumpet. To Stillz it sounds like a voice, like a old-ass bluesman howling about his pain. Ahmad Trench had hooped here as a youngster. One basketball goal is crooked to the left. Memory sends the ghost of a Spalding arcing through the air toward the absent backboard at the court’s other end. Swish.

I’ma donate like half a millie to rebuild this park, Stillz says.

The sun’s fading when they climb back in the Phantom. A few more intersections and they roll up at what should be a purple and green shotgun with gold fleur-de-lis stenciled on the doorframe, like she had wanted. What they find is three concrete steps that lead to a porch and a flood-stained yellow door still in its frame. No roof, no walls, no house.

It’s not Mr. Stillz but Ahmad Trench who walks up those steps, who stares at that door that leads to nothing, just a yard littered with scraps of other people’s lives. Memory supplies the side of the house. Ronald perched above him on the ladder saying, Hand me that purple paint. They were fighting on this porch the day she died. Memory supplies her voice: We been over this, Ahmad, and his own: He ain’t my daddy, he ain’t blood. Then the El Camino, the ski-masked goon with the chopper, the gunshots and echoes. The house-front splattered with Ronald’s skull, blood sliding down the door into his mama’s hair.

A pelican explodes into flight with a squawk and Ahmad starts kicking the door. It’s still locked and he kicks it until the wood splinters around the deadbolt.

Where all the lights in my city go? he says.

Junior—

Tyrone watches him going at the door. It cracks free and swings open. When it rebounds he kicks it until it falls off the hinges, clattering onto some planks.

How they ain’t got the power back yet, huh? Where all the lights go?

Tyrone manages to wrap him in a bear hug and carry him off the porch, saying I got you, I got you. The bodyguards don’t know what to do—they just stand there ready for whatever.

That was my mama’s house, Ahmad says.

Junior, we gonna grind through this.

Grind through this? You don’t understand. That was my mama’s house.

Tyrone thumbs away tears on his son’s cheeks and kisses him on the forehead. Ahmad raises his eyes to the sky and says, For goodness sake, Paw. For goodness sake.

They ride out to Stillz’s mansion in New Orleans East. It’s undamaged except for the two feet of flooding they have to wade through, ruining their pants and kicks. That house, that’s where it happens for the first time—for the first time without women involved. The first time it’s just them.

They send the goons off to get food, and in the stink of a flooded house without power, they trudge up to the second-floor Jacuzzi. Everything’s dark, flashlights and candles the only light. They have running water, at least, and it’s cold. They strip down to their draws and slide in: instantaneous relief. Stillz feels human again. Tyrone moves over and puts an arm around his shoulder, asks if he’s all right. It’s not a big thing, but Stillz rejects it. He knows he ain’t supposed to feel what he’s feeling. He knows he’s high. Then he decides none of that matters. He clutches Tyrone’s skull and kisses him roughly, teeth against teeth. Tyrone pulls away and says, You sure you want this? Nothing we ain’t done before, Stillz says. That was different, though, Tyrone says. Stillz says, I want this right now, and he’s pulling on Tyrone. They slide off their draws, towel dry, and move to the bedroom. Tyrone gets on his knees, reaching, but Stillz tells him, No, on the bed, on your back. He opens a bedside drawer and takes out a tube. With squeaky, glistening pumps he slicks himself. Heat rises in him with the force of hatred and he pulls Tyrone to the bed’s edge, grabs him by the ankles, and plunges in. Tyrone makes a choking sound and says, Easy, easy. Until he’s synced up with Stillz’s rhythms, Tyrone winces, holding the backs of his thighs. His eyes wobble. Stillz looks into them and for a moment feels something like love shoot through his angry lust. And then the feeling fails. He’s glad it’s dark. The smell of stagnant water hovers up through the shadows.

When it’s over, his heart grows polar-bear cold. I ain’t no fucking homo, he says.

But it keeps happening. It keeps getting harder to deny.

After Katrina they move to Miami and Stillz cranks up the volume on his swagger. He hits the weed and syrup harder. He grows his dreads out, loses count of his tattoos, and starts calling himself The G.R.I.E.F.—The Greatest Rapper in Existence, Fucker. The hip-hop community blah-ha-has. Nobody from New Orleans will ever be the King of Hip-Hop. At best, he’s The G.R.I.T.S.—The Greatest Rapper in the South. Mr. Stillz deserves only one title: The M.D.M.A. (Most Delusional MC Alive). Maybe if he popped less MDMA he could actually rhyme.

In 2006, Stillz charges $50,000 a verse for each of his 100-plus features. He puts out six free full-length mixtapes—no choruses, just rhyming over other rappers’ beats—the best shit he ever makes. Drug ballads knock nipples with anti-Bush rants. He seasons his verses with little dashes of French, the cayenne pepper for his gumbo flow. Rolling Stone, Spin, Pitchfork, Blender, XXL, and The Source all rank at least one of his mixtapes on those best-of-the-year lists they love to make. Then, in summer ‘07, when he releases the long-awaited studio album, The G.R.I.E.F., it’s Vibe who finally cops to the truth. All right, fuckers, it’s official: he actually is the greatest rapper in existence.

The crown arrives in the form of six Grammys, and that’s when the photo emerges.

I know all about the sizzurp. I know how to concoct it. What you do is dump some Sprite out of a two-liter to make room for a pint of codeine cough syrup. Put the cap back on. Turn the bottle upside down: the syrup bleeds into the soda, turns the bubbles Easter-egg pink. Some people slip in Jolly Ranchers for extra sweetness but not Stillz and not me. Let the foaming subside. Pour it in double-stacked Styrofoam cups and sip it till you’re moving in slow-mo. When you lean hard and smoke trees on top of it, you feel like the combo might wash you right out of consciousness. I’m far from all-day-every-day like Stillz, but I’ve felt that blue coil of warmth in my stomach radiating out in slow throbs, so I know how he feels that night in Miami. He’s nodding on his black leather sofa as the TV screen scatters the room’s shadows. He reaches for another blunt: only two left in the package. He’s too woozy to holler for T-Rell the Weed Doctor to roll more. He can’t really feel his face but he’s used to this numbness—he did a mixtape, after all, called So Comfortably Numb, the one where he rapped over classic rock instrumentals.

DJ Red Beans is down the hall mixing the tracks they recorded earlier. As long as Stillz lays down at least four verses a day, he knows he’s still the greatest rapper in existence. Nobody else is that dedicated. Nobody’s got more words than him. He flips through the channels, lands on BET, and suddenly Tyrone’s ranting at the camera. For the first time since breakfast, Stillz takes off his shades.

Look here, mane, they call us Wreckless Records cause we don’t never crash, and if your record is a smash, we can still survive. Stizzle was my main focus, but I’m trying to bring new artists to the world. And my man Splack Diggity coming home from the pen next month, finna get his shine back. It’s going down like the Titanic, you heard me? Stizzle can go get his by hisself. I’ll see him in the streets, though. I see you, Mr. Stillz, I see you.

Stillz thinks: So it was Splack. I knew it. Acting like a bitch cause I blew up and he got sent away and then his dumb ass got extra years for trying to smuggle in dope through a football. Now he’s finally getting out and he’s trying to take my shine. And Tyrone’s making it happen.

Oh, he want beef? Stillz is shouting. He want beef?

He throws the remote at the wall and the batteries roll around on the floor like marbles. He springs from the couch, jumps up and down to shake out the numbness. Nobody can challenge him and survive. Surging with post-nod energy, he shadowboxes his way down the hall, jabbing and uppercutting to the sound of his own voice booming from the speakers in the room where Red Beans sits twisting knobs. Stillz goes into the booth and adjusts the headphones over his dreads.

Alright, Beans, lemme rhyme over Tyrone’s new track.

“Still Shining”?

Yeah, but we gonna call ours “No Homo.” Get that yellow tape out: this here’s about to be a murder scene.

This is what he freestyles:

Ugh, no homo but we cockin em.

The pistol said it’s time, so I’m bout to start clockin em.

And I keep poppin till they tell me to pause—

No homo but Ralph Lauren is all over my draws.

Errbody keep tellin me to call Tyrone,

But I don’t keep no faggot’s number on my phone.

I tote all my chrome, shoot sharper than a spear, bitch.

Point it at your dome, homophone, you on that queer shit.

I’m on my Richard Gere shit, pretty women love me;

Mane, you lookin Dennis Rodman: gay as fuck and ugly.

Yeah, I’m gettin mad hoes like I was a tool shed.

You on that shit that turn a motherfucker’s stool red.

No homo, but I’ll blow off a fool head.

Bury yo ass like a farmer when the mule dead.

And even though I got two babies on the way,

I throw in that “no homo” so you know that I ain’t gay . . .

He goes hard like that for four more minutes. He slams Splack Diggity, too, but Tyrone gets most of his venom. When he leaves two days later for a string of shows in Europe, “No Homo” is out in the world, and my heart floods with hurt for Tyrone.

Paris. The Four Seasons. Above the Marble Courtyard in his presidential suite, he wakes up congested and feverish in a tangle of bodies. He blinks at the space, trying to reconstruct the night. Three broads and DJ Red Beans sprawl around him in bed. Heels, dresses, jeans, and g-strings are strewn across the floor. Condoms, condom wrappers, K-Y, champagne flutes, roach-filled ashtrays, Styrofoam cups stained purple. His clothes rest on a lacquered table and—what the fuck?—they’re neatly folded. He’s wearing socks, shoes, and nothing else, like a porn star. The early sun is blunted by the room’s blue curtains. Stillz jumps when his iPhone vibrates, but the other bodies seem comatose.

As he shivers toward the bathroom, a couple of his rhymes come to mind: Call me Herod, I get head delivered to me on a platter / And the ice in my mouth could make your fucking teeth chatter. What track was that on? When did he record it? No telling. So many rhymes, so much boasting and bragging, and for what? He opens his mouth for the mirror. Light drains through the skylight and catches his grill; the sparkle just don’t thrill him like it used to. He sits on the toilet and samples his voicemail. Both his soon-to-be baby mamas are tripping. Expensive fallout from the canceled shows in Amsterdam and Berlin. An artist he sampled without permission is suing. Reviews of the mixtape: largely negative. Gay rumors: buzzing like horseflies. He lets only the final message play all the way through:

Junior, it’s me. Calling to apologize. That BET thing, that was just stunting. I ain’t even mad at you—I taught you to put business first. But you still my son, you heard? I look at you and I say, That’s love right there, that’s life right there. Fuck the money, fuck the record label, Junior. You my little son. You need to holler at your daddy and tell me what’s good.

Stillz texts T-Rell the Weed Doctor. He’s gonna need a whole forest of blunts to survive today.

He emerges from the Four Seasons into the bright cold, armored in his pretty-boy-gangsta style: black pea coat, grey cashmere v-neck sweater with scarlet lozenges, matching scarf, PRPS Barracuda jeans, and a fresh pair of Supra Muska Skytops, the tall tongues swallowing the cuffs of his denim. Then he’s in his limo. It takes him toward his private jet for a nonstop flight to NYC. The Parisian streets speed past his foggy peripherals as he blazes up and sips his breakfast sizzurp. Then he’s on the jet, literally lost in the clouds. Wednesday slides into Thursday. Thursday means an interview on HOT 97, a photo shoot, other celebrity shit. He ain’t nervous about that. He’s nervous about Friday. For the first time since the photo leaked he has to perform in New Orleans. And rumor has it Tyrone might show.

HOT 97’s Wanda Velazquez is up first. They start off breezy but she brings the real talk with quickness:

Q: So . . . what’s up with all these canceled shows?

A: Too much weed and sizzurp, baby.

Q: Don’t you think it’s time to slow down a little?

A: Homegirl, I appreciate your concern, I really do. But what I pour in a Styrofoam cup is my business, not nobody else’s.

Q: Y’all heard it from the man himself: he’ll put whatever he wants in that Styrofoam. Now, Stizzle, tomorrow’s Halloween, you’ll be back in New Orleans for the first time since the split with Wreckless—we feeling a little nervous?

A: I’m not nervous, no. Every time I rhyme, New Orleans talks through me because I am the streets. I’m just going back home where I belong.

Q: Can you tell us about your beef with Tyrone?

A: Download my new mixtape, Call It a Comeback. I express myself through music.

Q: The photo—is it real?

A: Like I say, I express myself through music.

Q: But then this whole “no homo” thing … if you’re not gay, why you feel you have to keep stressing that in your lyrics?

A: Bitch, I’m so high right now we ain’t in the same galaxy, and you sit here and judge me? What I do is my business. I fuck who I want to fuck, period. This interview is over.

He throws the headphones off and rolls out. His body’s so thick with syrup his limbs feel like slow-motion monsters. His crew flurries and jabbers around him. In the hallway he punches the elevator button then rips a framed painting off the wall. The shatter of glass is like a burst of melody, followed by jagged silence. The elevator takes forever. Too many motherfuckers around him, too much time to think. He thinks about fucking Tyrone, how raw and amazing it could be. How none of his bitches had it like that. He wasn’t no homo—just because you fuck a man don’t make you gay. The elevator dings open. He leans against the back mirror and slides down it. He blew it all because some bitch asked him a question on the radio. He fucked Tyrone over for this? For this?

Why am I so obsessed with Stillz? Why him and not some “socially conscious” rapper? The critics claim he has nothing to say, but goddamn does he say it—the most stylish nothing. To hear him in his prime is to hear a man delirious with his talent, flinging out onomatopoeic neologisms, pop-culture references, dizzying internal rhymes, scat jokes, and witty nonsense, every bar a pun or a punch line. The critics are also wrong. There’s pain coursing through all his best music. It’s just hyper-compacted, snagged in a phrase or tucked under a silence. His soulful eyes brim with the sorrow of a sunken city, the sorrow of men like I once was: covering up shame with defiance, cringing in the closet. He’s my modern-day Rimbaud, and Tyrone’s his poor Verlaine.

I got a privileged glimpse of that sorrow the day of his Halloween performance in NOLA. His team swept him on the quiet into the downtown W Hotel, and I was waiting down the way at Whiskey Blue. I saw him crossing the lobby. Mr. Stillz, I shouted, approaching with a folded-up poster. Already two bodyguards were moving toward me, looking mad ready to handle me if needed. But my man stopped them. It’s cool, he said, let the homeboy holler.

Yo, man, I said, I just gotta say I been feeling your music since the Tech Toters blew up in ‘96. Can I get your autograph on this here?

‘96, huh? That was the days. Who should I dedicate it to?

Charles, I said. Charles D’Ambreaux.

Damn bro? Boy, that’s a name right there.

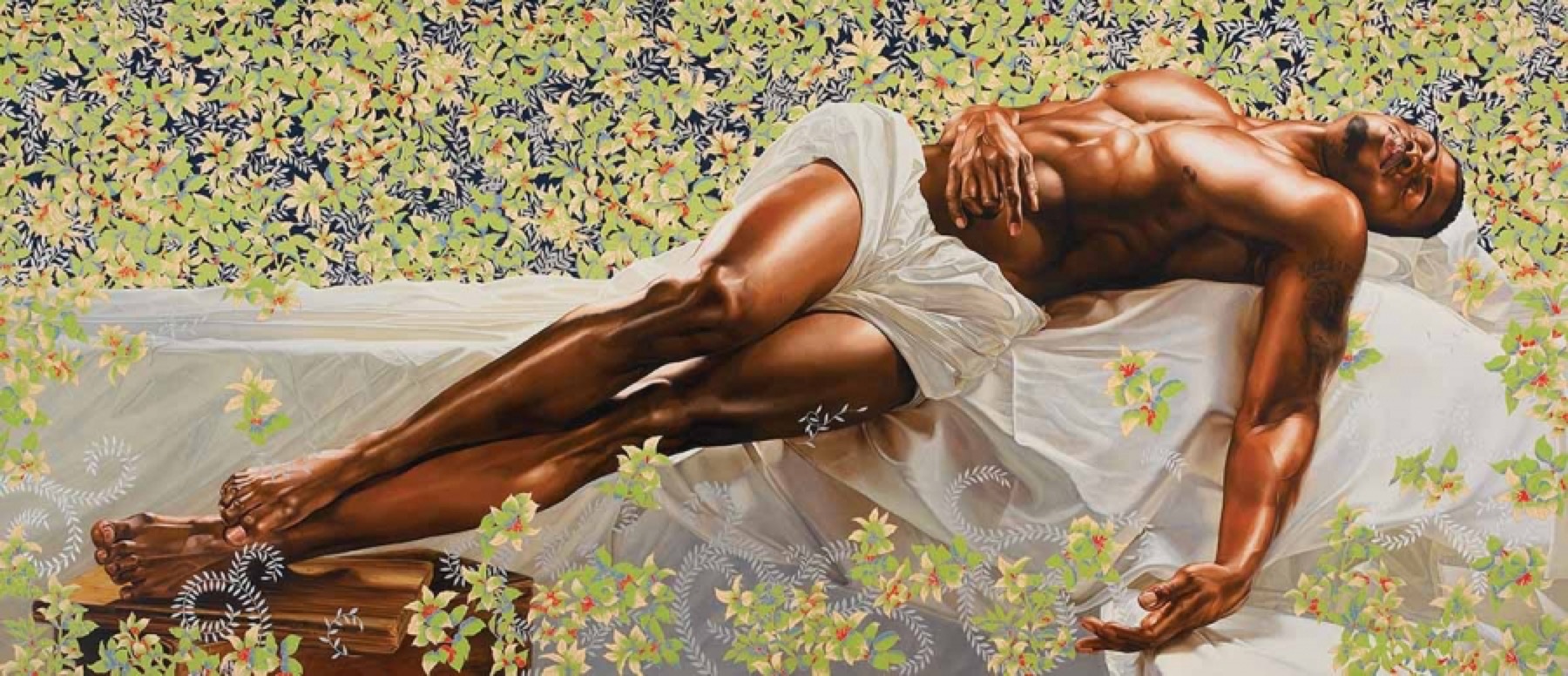

He unfolded the poster. He didn’t recall the photo shoot, I could tell, but he knew it was right after he went solo: his cheeks still puffy, still rocking the afro. He and Tyrone are shirtless, posted up in front of a Mardi Gras-colored house: 730 Flood Street. He has a tattoo of Tyrone’s face on his chest; Tyrone’s got Stillz’s face on the same spot. The poster is a capsule of his losses: his mama, her house, his city, his career, his daddy. Behind the sunglasses his eyes were pooling—I swear I could feel it. He was thinking: Fuck the money, fuck the label. Like Tyrone said.

He shook his head like he was about to say something heavy, but he busted out with, Goddamn that’s a old-ass picture—that was my first Rolex!

Everybody laughed, Red Beans, the bodyguards, the assistant who handed Stillz an ink pen. Then his face went serious again. He said, You know what? I think I’ma call Tyrone right quick.

For real? Red Beans said.

For real, he said. I think I need to call Tyrone, he said. I think I better call Tyrone.

And I was there, hope blooming inside me. I thought, Maybe they’ll be brave enough to come out together, to say fuck the haters, to say there’s no reason to front about who we really are.

They didn’t do that. They claimed the HOT 97 “confession” was a misunderstanding. They said the sex never happened and tried to go back to how things were before the scandal. Maybe they’ve found some down-low way to make it work. Or maybe they really ain’t gay. Maybe I just need them to be. Because I can understand denial and protesting too much (been there, Lord knows), but I can’t stand the thought that a man—a poet—I admire so much is just a run-of-the-mill homophobe. And come on, that lawsuit? No way he left because of money, not at that moment and not like that.

He’s still around, still omnipresent, even, but to diminishing effect. That stream-of-consciousness fever has broken: drugs and complacency at work. He’s fading into the Zeitgeist he created. But I like to linger in those pre-”No Homo” days when his lyrics exploded from the speakers, volcanic and addictive. I linger in the hotel, in the only moment I ever got with him. Even though the W was low-lit, I felt as though the sun were blazing through stained glass for our benefit. That poster I offered up seemed to alter him. Every fan wants to make his presence felt, to register on his hero’s private Richter scale however slight the quake, but this was so much more. I was fresh out of the closet myself, family and friends turning against me. What can I say? Symbols are important, symbolic victories, and what a message it would’ve sent. Everything seemed possible in that moment. Art. Revolution. Forgiveness. And I cannot convey how the joy flowed through me when, on a strip of sky above his mama’s home, Ahmad Trench—the Trench Sweeper, Mr. Stillz, the Greatest Rapper in Existence, Fucker—inscribed the following on my poster:

For Charles Damn Bro,

Stay real, brother

—The G.R.I.E.F.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.