Will Davis Campbell (1924-2013)

Back in the early ’90s, my wife and I were in Nashville for the Southern Festival of Books, one of the first I attended, and I was impressed to see that a generous number of black writers had been invited to read and present their books. I had time to circulate and noticed an uncomfortable fact of book life. In the lines where readers waited to get writers’ signatures on their books—Jimmy Carter’s line was two blocks long, I remember—it was painfully obvious that black readers were buying from black writers, and white readers from whites. Book-signing lines gave the impression of being segregated. There was one flagrant exception, a fully integrated book line, with perhaps more blacks than whites, waiting to secure the signature of the Reverend Will Campbell. And his black readers were not customers only, but apparently personal friends. Way back in the line people were hollering at him and joking with him, so much that it was hard for him to focus on the title pages he was trying to sign.

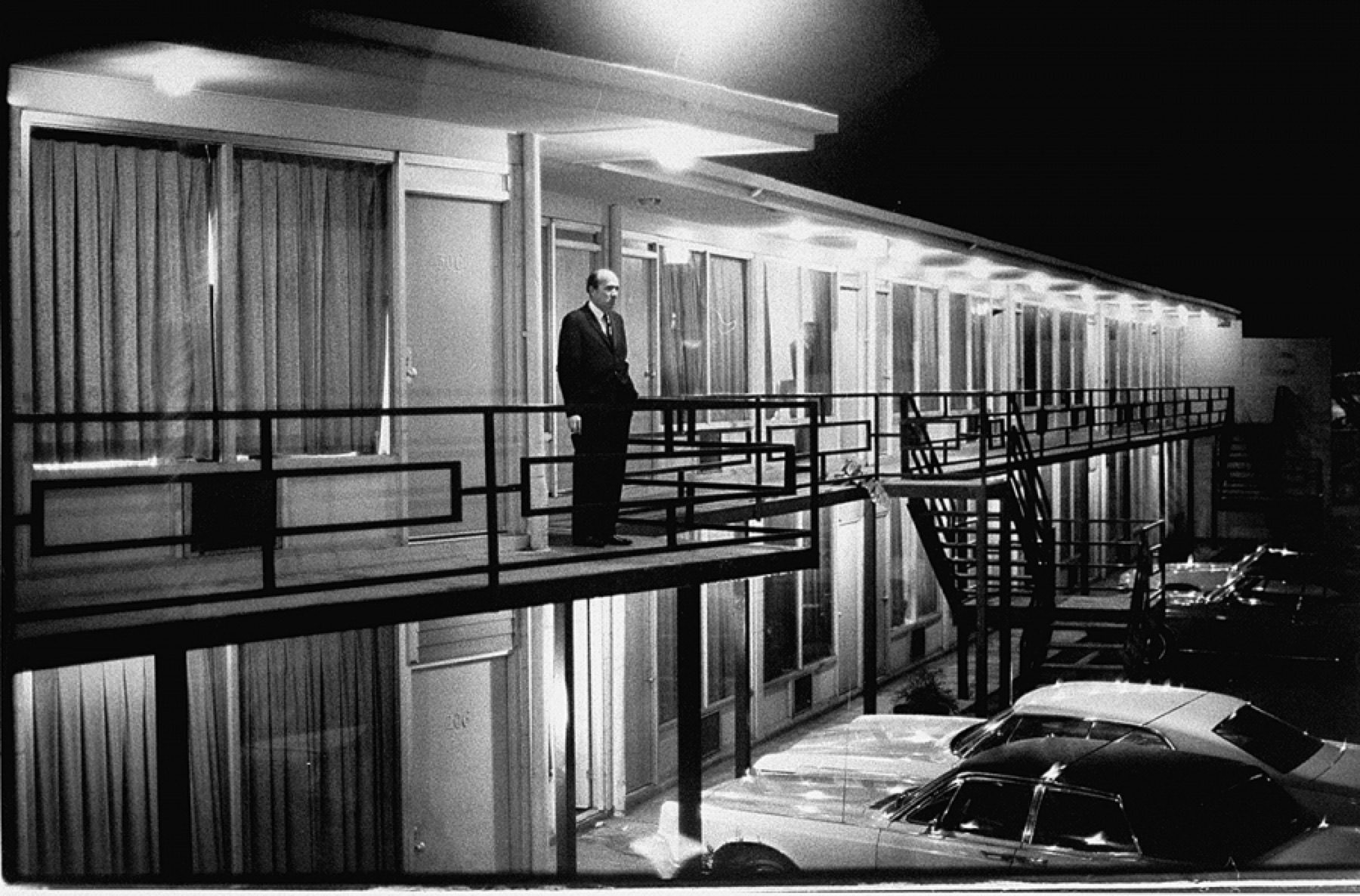

I hadn’t met Rev. Campbell, nor at that time had I even read his celebrated memoir, Brother to a Dragonfly. I knew him by reputation only, an alternative sort of clergyman who served as unofficial chaplain to a community of Music City irregulars. As a spiritual advisor he came highly recommended by a wide range of Nashville types that included some of our friends. I’d heard that his chaplaincy at the University of Mississippi, in his native state, had been terminated because his enthusiasm for integration attracted death threats. I’d heard that he drank beer with Thomas Merton. I didn’t realize the extent of his involvement in the civil rights movement. I was not aware that he was the only white man invited to the meeting that launched the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, that he had marched with Freedom Riders in Alabama and run the gauntlet of racist thugs with the nine black students who integrated Central High School in Little Rock. For those who knew that he was a trusted friend and confidant of Martin Luther King Jr., the lone white friend who came to pray with King’s family after the assassination in Memphis, I guess it was no surprise to see black people hailing him like family in Nashville.

Later I had the good fortune to join Campbell’s extended congregation, a privilege that included pilgrimages to his home place in Mt. Juliet, Tennessee, where pastoral consultations might include drinking whiskey and listening to Will sing scabrous ballads to his own guitar accompaniment. Cussing and praying were not incompatible in his religious worldview, where the sacred and the profane were as inseparable as God’s children, white and black and all shades in between. In Mt. Juliet no pilgrims were turned away, and none were confronted with their sins and errors. Will could homilize with the best of them, but he was just as comfortable listening, nodding benevolently, whittling away at the whimsical walking sticks he bestowed on his friends. Nonjudgmental? That’s not for me to say. Rev. Campbell was nonjudgmental on the surface, to a fault. Like many people who influence others profoundly, he combined ample external confidence with a core of impregnable humility.

I

t’s unnecessary to explain, to anyone who knew Will Campbell, why he was one of the most remarkable and valuable Southerners of his generation. Mention his name and his parishioners will just grin and shake their heads. But for those who never had the privilege of meeting him, it’s important to place him in a proper context, free of stereotypes and received ideas. He was invariably described as a “maverick,” “renegade,” or “curmudgeon,” words that subtly, sometimes condescendingly, distance their subject from the mainstream of respectable opinion. Just a shade removed from “crank,” “curmudgeon” is often fastened to citizens who bear truths that not everyone wishes to hear. Campbell bore many in his time. But he was never a calculating contrarian, ever a by-God original. He believed in the Gospel of Jesus Christ, put it on like a coat that fit him and took it places where it hadn’t gone before. Of the many categories that included him—Christian, Southern Baptist, clergyman, theologian, liberal (even “redneck,” which he embraced cheerfully as long as it came without a Yankee sneer)—there was not one of which Will Campbell was even remotely typical.

“I’m seventy-six, I’ve been all over the world, and I’ve only met one Will Campbell,” marvels Nashville songwriter Tom T. Hall, a longtime admirer. “There must be something special about him.” What set him way apart, to begin with, was a moral compass tuned to True North—or True South, I suppose. A south-Mississippi “deep water” Baptist who was called to preach the Gospel at the age of seventeen, he derived his politics and theology from the New Testament as he interpreted it—not from his intellectual friends, though he had plenty, or from other books, though he’d read plenty, too. The Sermon on the Mount was the text for his belief that a true Christian always sides with the powerless and the marginalized. The chasm of difference between Will Campbell and those Southern preachers better known to America—Jerry Falwell, Pat Robertson, Jim Bakker, Jimmy Swaggart, even the sincere but intellectually challenged Billy Graham—is so vast that only Jesus could have bridged it. Will once described televangelists as “electronic soul molesters,” and admitted that they sorely tested his personal gospel of unconditional forgiveness.

In one sense Jesus is always an imagined figure, historically indistinct and far away, and the great strength of rare believers like Will is that they can imagine Christ so vividly they almost resurrect him, body and blood. It’s likely that the actual Jesus would have abhorred many Southern Christians, for their hypocrisy and false piety and especially for their preposterous certainty—always denied, yet pathetically obvious—that Heaven itself was segregated. And perhaps Hell as well. But Jesus, despite language barriers and culture gaps, would surely have taken a shine to Will Campbell. When I compare Brother Will to some oleaginous bigot like Pat Robertson, I think of the scene in Crocodile Dundee when a New York thug pulls a knife on Paul Hogan, and Hogan, producing a blade the size of a scimitar, says, “That’s not a knife—that’s a knife!” That’s not a Christian—this is a Christian!

A lesson all Will’s congregants learned well is the difference between a commitment to social justice, which means acting always in a way that you believe will help the underdog to prevail, and political correctness, which means always agreeing with the underdog and parroting his language on every issue that concerns him. Rev. Campbell, who chewed tobacco and deplored abortion, was about as PC as a Bengal tiger, and he valued knee-jerk liberals about as highly as he did televangelists. The night before Will’s memorial service, I had dinner with North Carolina novelist Wayne Caldwell, another Campbellite, who complained that New Yorkers have asked him how he could call himself a Baptist, as if it were synonymous with superstition and political reaction. “I tell them I’m a Will Campbell Baptist,” Caldwell said, “and let them figure it out.”

H

e wrote a score of books and won prizes for many of them, but not every chapter and verse of the Gospel According to Will was crystal clear to his adherents, not even to the most loyal and attentive. The writer John Egerton, who was Will’s close friend for decades and in later years served him as a kind of consigliere, admitted after Campbell’s death that the holy man’s logic sometimes escaped him. “I never understood a lot about him,” Egerton allows. “But he was no phony.” Particularly difficult for Christians of weaker conviction was Will’s insistence that Jesus forgave the worst criminals while their hands were still bloody, a radical belief that compelled him to counsel Klansmen and racist assassins, and to visit James Earl Ray, King’s murderer, in his prison cell. “Hate the sin, not the sinner” is an ambitious moral goal to which many pay lip service (most often, it seems, to deny their homophobia), but Will Campbell made it the cornerstone of his faith. As he was quoted repeatedly, “If you’re gonna love one, you’ve got to love ’em all.”

The way Campbell saw it, only a small percentage of God’s children can ever find and steer their lives by the light of reason, but that didn’t exclude the rest of His children from the light of His love. Who, Will might ask, needs help—or love—more than a benighted, hate-poisoned Klansman? I could see the sense in that. But the old deep-water religion and the doctrine of universal amnesty were a harder sell to someone like me, the product on the one hand of four generations of Unitarians and, on the other, of untold centuries of vengeful Celts. But Will didn’t proselytize; he was a pastor, a shepherd, not an evangelist. If you disagreed with him, he only needed to be sure that you’d thought it through with care, that you hadn’t recycled some cheap piece of conventional wisdom. If you said something harsh or stupid in his presence, he’d look at you with mild disappointment, as if he’d just bitten into a sour apple, and with real concern, as if he was ready to help you if you asked him. Such was the agreeable flavor of his ministry.

It was a hard road Campbell set himself to travel, and he could be hard on himself. He warned me once about a bad person we both knew—I wish I had listened more carefully—but what tormented Will was not the trespass committed against him, but his uphill struggle to forgive the trespasser unconditionally. A friend described Will as “obsessed with grace.” He was one of a kind, a Dixie Diogenes navigating by his own light, searching for honesty and virtue in a troubled land. This was a Depression-era cotton farmer’s son from Jim Crow Mississippi who decided, at the age of twenty, “This is what I will do with the rest of my life—try to rectify the evils of racial injustice.” His underdog theology led him from integration to the antiwar movement, to denouncing capital punishment and championing the rights of women and gay people. At a time when the South as a whole is not distinguishing itself for creative thinking, moral vision, or progressive politics, we might ask ourselves how someone like Will Campbell came about. Could we clone him, find a way to breed more of him, or was he just a rare gift from a tired gene pool—or as he might say (but never about himself), a manifestation of the grace of God?

“Will Campbell was a sage,” eulogized Congressman John Lewis, a surviving hero of the civil rights movement. “He was a gift to America who never received the recognition he truly deserved.” Another admirer characterized Will as “a man of many disguises,” and as John Lewis and his colleagues remember him, he sounds almost like the Lone Ranger—wherever injustice and oppression soiled the Southland he would appear mysteriously, a black hat on his head and forgiveness in his heart. The day he was memorialized in Nashville, my wife and I held our own modest memorial in the Yankee-haunted north woods, a service that consisted mostly of listening to gospel standards recorded by the late, great sinner George Jones, Nashville’s second most painful loss in the spring of 2013. “It Is No Secret” was the one that choked me up: “With His arms wide open, He’ll pardon you. . . .” (“It is no secret what God can do.”) Right, Will. Sometimes—this time, anyway—I think I get it.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.