Leaving Day

By William Caverlee

The civic center arena in Monroe, Louisiana, opened in 1967 and looks like an airplane hangar. Directly behind the arena and connected to it by a wide alleyway is an open-air pavilion, where municipal odds and ends are stored—fractured dumpsters, defunct Coke machines, a mountain of folding chairs. This is also where eighteen-wheelers and motor homes that belong to traveling productions like the James Cristy Cole Circus are parked during appearances in Monroe. On a Monday morning in early March, after the annual Shrine circus has wrapped up a three-day run, James Plunkett is trying to go home.

It’s cold and windy with a scent of manure in the air—the calling card of eight tigers, two bears, two camels, one elephant, and about a dozen each of horses and dogs. Most of the acts have left already and are driving west toward Mabank, Texas, near Dallas, where Plunkett lives with his wife and circus co-producer, Cristine Herriott-Plunkett. Next week’s Shrine circus in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, has been cancelled and thus everyone has a week off before heading to Lincoln, Nebraska, for a five-day stand.

Plunkett’s two sons, Jesse and Cole (“The Plunkett Bros. Trampoline”), left immediately after the last performance Sunday night so that Cole could be at Mabank Junior High this morning. Jesse, a freshman at SMU in Dallas, wanted to stay in Monroe to help break down the circus, but his parents insisted that the two boys hit the road. Cristine departed early today in the family motor home, pulling a trailer with her ten dogs. Cebero, her show horse, and her three miniature horses are in another trailer driven by the Plunketts’ niece, Rachel (foot juggler), who is also ferrying the string of ponies and the lone camel that audience children ride before and after performances and during intermission. (James, speaking of Rachel: “She’s the best driver we’ve got.”) The Plunketts have forty acres in Mabank, where their menagerie is stabled between road trips.

Thus, the circus is stretched out for 250 miles along Interstate 20 from Louisiana to Texas. By the end of the day, James Plunkett will have to deal with five or six automotive breakdowns: wheel bearings, flat tires, a stuck throttle on one of the diesels.

But for the moment, he is still in Monroe, dealing with the kid.

The kid joined the circus this past fall as a stagehand and laborer. Lately, he works mostly with the horses. He’s from Missouri and plans to drive home after the Monroe show, spend a week with his mother, then rejoin the show in Nebraska. But his 1995 Dodge pickup won’t run. Everyone believes it’s the starter. The kid, twenty-one years old, is tall and gangly and wears glasses and a sweatshirt with “Mizzou” emblazoned across the front. He stands beside his defeated Dodge, arms crossed, shuffling his feet, waiting for something to happen.

James’s cell phone rings. It’s Cristine, who has just had to pull into a truck stop in Shreveport, a hundred miles to the west. There’s smoke coming from one of the axles on the trailer she’s pulling. This will turn out to be a blown wheel bearing, first of the breakdowns James will tackle on this long day. Hold on, he tells his wife. “Soon as I get this truck problem solved, I’ll head your way.” James turns and looks over at the kid, still standing beside the comatose Dodge.

James Plunkett is fourth-generation circus. He tells me his great-grandfather and grandfather once toured with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show. Later, I check the dates: W. F. Cody died in 1917; James’s great-grandfather was born in 1840-something, his grandfather in 1886; the numbers fit. From the 1920s to the 1940s, the Plunkett family crisscrossed rural America—in a kind of vaudeville/circus/variety show, with songs and skits, feats of strength, tumbling and gymnastics. James hands me an iPad with grainy photographs of his father, grandfather, aunts and uncles, a circus tent, an ancient concession stand on wheels. James and his brother Jeffrey had their start in a trampoline act—the Plunkett Bros. Trampoline—the same name that Cole and Jesse are continuing today. In his heyday, James performed a comedy wire act, traveling to Europe, Japan, Hong Kong, and Canada—an act that was taught to him by Hubert Castle, a famous tightrope walker with Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey in the first half of the twentieth century. Castle appeared on the cover of Life magazine in 1941.

Shrine circuses are James’s bread and butter. The fraternal organization Shriners International is probably best known for its twenty-two children’s hospitals spread across the United States, with locations in Canada and Mexico as well. Many local chapters, like Monroe’s Barak Temple, sponsor annual circuses as part of their fundraising program. Most years, the James Cristy Cole Circus will make stops in Nebraska, Louisiana, Arkansas, Missouri, Oklahoma, and Minnesota, accruing eighty, sometimes a hundred performance days. High season runs from February to June. At the end of June, James returns to Texas—summers are not good for circuses because so many families are on vacation. Things crank up in the fall for a short season, then it’s back to Texas for the winter break.

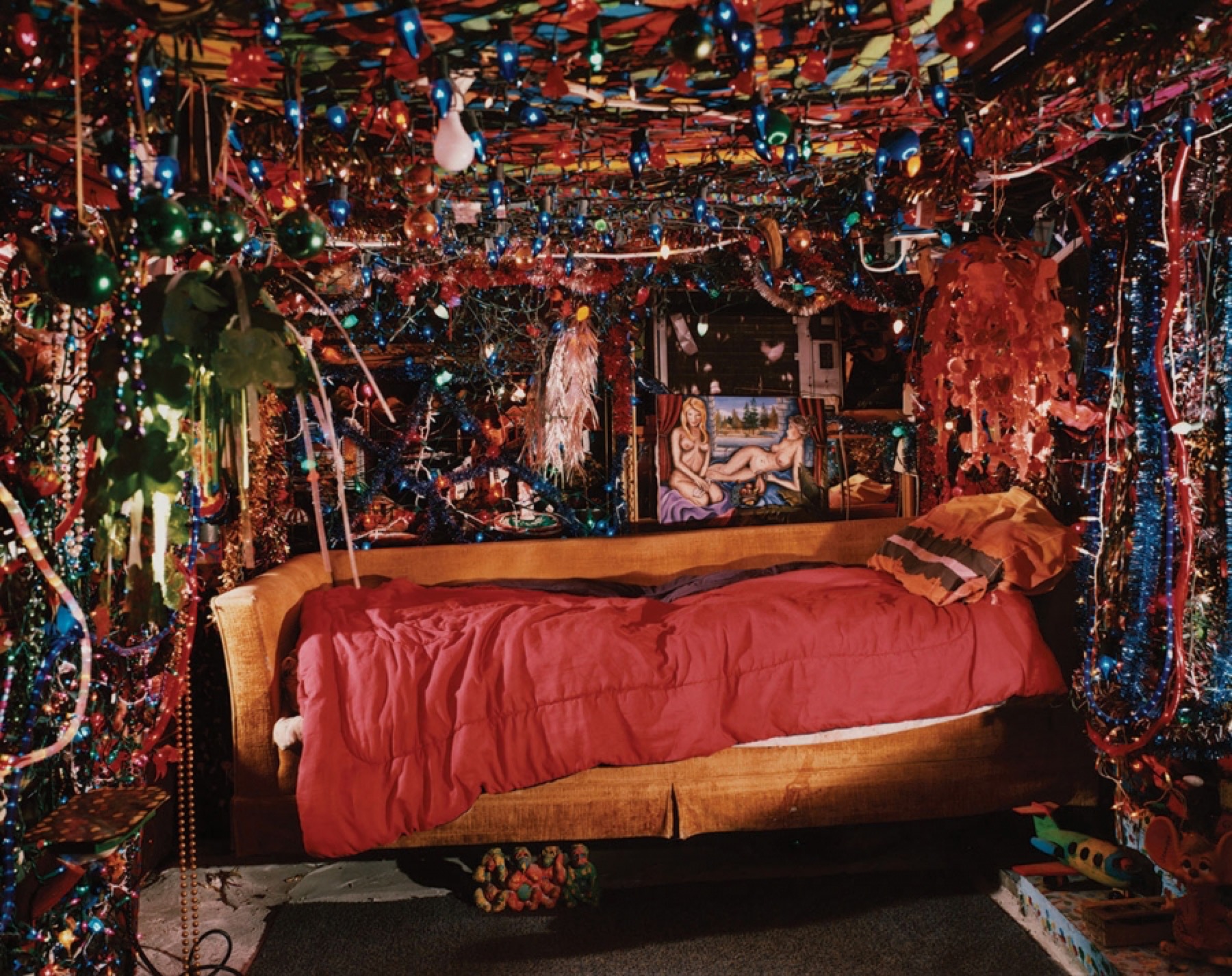

The only reason Star Plunkett is still in Monroe is that her Alaskan malamutes travel in the eighteen-wheeler that her father drives (James: “I’m usually alone in the cab, since no one else likes my taste in music”), and she refuses to leave without her dogs. She will be driving a one-ton Chevy Duramax, pulling another trailer filled with circus gear. The one-ton will have a flat later today in nearly the same spot on I-20 where Star’s mother broke down. Star’s home is the front half of the rig her father pulls. She shares quarters with seven dogs, as well as a load of circus mats, sound equipment, banners, signs, and ring curbs—the interlocking wooden barriers that form the circus’s three rings.

“I live here full-time,” Star explains. “Even when I’m home in Mabank. That’s my bed up there, above the dogs, sort of a loft.” Her apartment contains a shower, toilet, and kitchen. Also, her sewing machine, since it’s Star, along with her mother, who creates most of the costumes—sequins, feathers, glitter, and glam—for herself and for her mother, her Aunt Wendy (aerialist), and Laura (aerialist, singer, mistress of ceremonies). “We can switch around and wear each other’s outfits,” Star says. “We’re all about the same size, and, well, it breaks up the routine to change costumes from time to time.”

“What if there’s a tear or a rip in a costume?”

“That’s why the sewing machine is with me. I make the repair, fix things during a performance.” In addition to her dog act, Star performs two aerial numbers, the Lyra and the Spanish Web, and paints faces during intermission. She tells me that she’s not performing her hula hoop act this year (“See her do 50 hula hoops at one time!”), but it’s available if needed.

Meanwhile, the kid’s still waiting for someone to fix his Dodge. By now, a mechanic has materialized from a nearby repair shop. The civic center pavilionis located in the rear of the complex, ina gritty, mostly black downtown area: railroad tracks, I-20, municipal maintenance shops, the Old City Cemetery. Since James has no car in Monroe—only his eighteen-wheeler—he has to walk wherever he wants to go.

I offer to drive James to a NAPA auto parts store to buy the new starter. During performances, James always wears a tuxedo: he is ringmaster, impresario, director, producer, a handsome man sporting a natty mustache. He fights a weight problem, worries about his waistline, but in the photo I have of him during his tightrope days, he’s trim, muscular, and fit, with a thick head of dark hair.

This morning he’s unshaven, rumpled, in sagging jeans and a faded windbreaker. His cell phone rings every few minutes. Each call brings a fresh problem to solve; still, departures are usually not this bad, he assures me.

“Do you know your way around the towns you visit every year?” I ask as we’re driving to NAPA.

“Not really.”

Yet he certainly knows the way to Captain Avery’s Seafood Market three or four miles north of the civic center, where he bought sacks of live crawfish for his annual crawfish boil after Saturday night’s performance—a gift to crew and performers. For a Texan, he’s an expert in this intricate Louisiana art: wielding propane cooker, heavy pots, Zatarain’s crab seasoning, potatoes, and corn.

Luckily, NAPA has the right Dodge starter, and James peels off three $100 bills. The counterman explains that he’ll receive a refund of $49 if he returns the starter core from the broken Dodge.

Back at the civic center, the kid tells us that the mechanic has left. For the first time that morning, I wonder if James is going to lose it, going to give the kid the heave-ho. As if on cue, the phone rings again: Cristine, still waiting at the truck stop in Shreveport. What’s the holdup?

The last two acts have departed: the Viorels from Romania (“Magical Transformations,” a quick-change act) and the X-Metal Riders. The latter is a twin bill consisting of BMX stunt riders and the “Globe of Death”—three motorcycles spinning simultaneously and insanely inside a metal sphere. James is essentially a general contractor: he maintains the circus’s props and equipment, plus a core of family members and employees. All other acts—the animal trainers, the Viorels, the X-Metal Riders—are subcontractors, responsible for getting themselves from site to site, responsible for their own labor and equipment. Now, at the civic center, there remains only James, Star, the kid, and me.

“Find a wrecker,” James tells his daughter. The two of them begin working their smartphones.

A few minutes later, he tells the kid: “Look, we’ve got a wrecker on the way. He’ll take you to a garage here in town where you can have the starter installed. You’ve got my phone number and here’s the number of my elephant trainer, who’s still in Monroe. He’ll get you out of trouble and loan you more money if you need. I’ll settle up with him later. Look, don’t forget to take the old starter back to NAPA for the refund, or I’ll kick your butt. Call me when you’re on the road.” Thirty minutes go by; the wrecker finally arrives. James gives a few more instructions to the kid, sends him on his way.

Three days later, I phone James in Texas. “Did everything turn out okay?” I ask.

“Oh, sure,” James says. “Everything’s fine. But what a day! It was 7:00 p.m. before I got home. We leave for Nebraska next week. Star’s outside right now tending to the animals. And I’ve got more truck repairs to get done.”

“What about the kid?”

“Who?”

“The kid with the broken Dodge.”

“Oh, him . . . Well, it was the starter, just like we thought. They got it repaired in Monroe and he called me from the road. He’s in Missouri right now. He’ll join up with us again when we get to Nebraska.”

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.