A Yellow House in New Orleans

By Sarah M. Broom

Did my childhood home fall apart so that something in me could open up?

All that is left now of that yellow house is a piece of concrete slab in the backyard where Mom hung clothes out to dry, and where, as children, we jumped rope with telephone cord. The house was demolished by the city, and not one of us twelve children was there to see it go. My mother, Ivory Mae Soulé, called me at home in New York, and told me the story in three lines:

“Someone said they went over to the old house and those people had knocked it down.”

“They say that land clean as a whistle now.”

“They say it look like nothing was ever there.”

I do not agree with that last line of hers. I went and saw it for myself. For the first time in my life I’d brought someone not of my immediate family to the house I grew up in. We stood facing a fifty-foot-long burrow in the ground beginning near the curb and running, shadowlike, the length of where the house used to be. My friend asked where certain rooms were, where Ivory and my banjo-playing dad, Simon, once slept. I tried to pinpoint them, but found myself confused.

“No, that was the kitchen.”

He asked where might the door have been because like me, he had the blaring feeling that it was wrong to be standing outside a family house, unable to enter into its commotion and introduce yourself by name: David and Sarah, here, together. There used to be three doors to this house: the front (into the living room); the side (into the kitchen); and the back (into the den).

No place to go now but into deep ground.

It is a bone-cold Harlem day. Sitting across from me on the windowsill are two artifacts belonging to the New Orleans ground that once held the yellow house I grew up in, into, and then out of. Half of a yellow, blue-speckled plastic fleur-de-lis wall decoration, and a silver spoon—bent and overused to paper-thin. Once, the spoon went missing in my duplex. I found it washed in a drawer amongst the utensils, and thought: No, you do not belong in there with all the others, you have not come from where they’ve come, before putting it back on the windowsill.

They have been there ever since; nearly eight months have gone by. I have not known what to do with them. I still do not. But I am leaving this place here on West 119th Street for Bujumbura, Burundi, and they cannot stay. I’ve put them in a Ziploc bag and placed them inside a box with “Misc-Fragile” written on top. Where, if at all, might I store these two things?

Just three months before Katrina, I had a premonition, so I sat down and wrote:

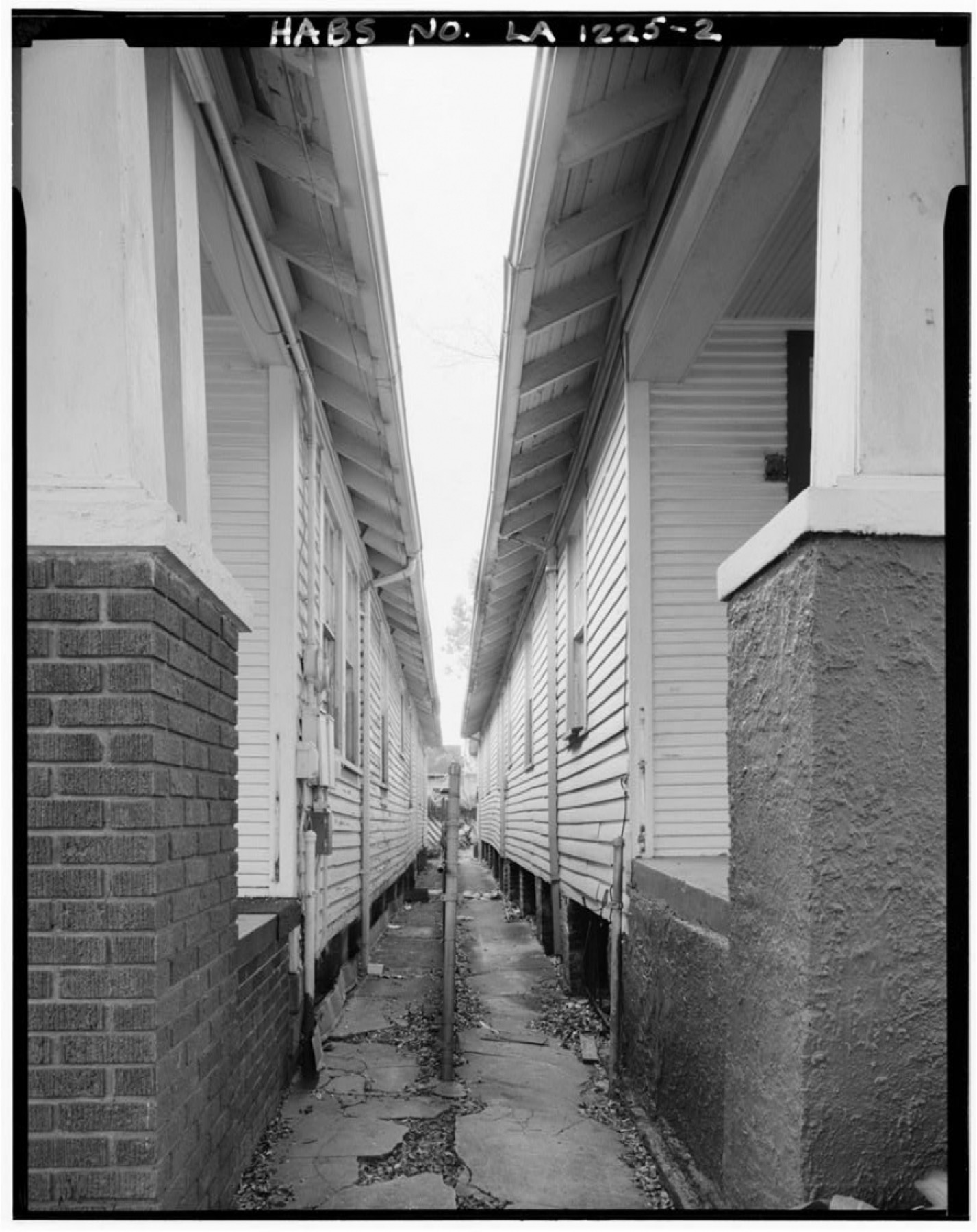

There is a narrow yellow paneled house in New Orleans that’s got a lean to it, a lean, that is, toward falling. It’s on the short, nearly forgotten end of Wilson Avenue, which should really be called a street since there is nothing grandiose about it. Though if it were called its true, true, name, this story would not be begging its way to the page. The Broom clan, five girls and seven boys, lived on the side of the street where there are only three remaining houses. Ours is the one begging to fall. And I don’t blame it.

When I wrote that, I did indeed want the house to go, but mostly from my mind, wanted to somehow be free of its lock and chain of memory, but still imagined it could be rebuilt. Did not, could not, foresee water bum-rushing it.

I have photos of the way the storm pimp-slapped, and made fun of the house, but only showed them once, to a New York friend, before embarrassment had me stashing the photos underneath the bed. My worry: People might be able to see that the house was raggedy even before the storm.

I grew up in New Orleans East, the area of the city developed as suburbs by a private company of the same name. To get to the yellow house if you were leaving the French Quarter area, where tourists mostly spend the night, you’d drive on Interstate 10 for ten minutes before exiting at I-90/Chef Menteur Highway. Before the storm, you’d see women standing in front of Natal’s (pronounced Nay-Tells) Super Market talking with each other, some of them wearing thin, pink house slippers with their toes hanging off, Newport cigarettes dancing off the edge of their lips. Now you will see nearly no one. You will drive past Causey’s soul-food restaurant and see a tour bus parked at the counter.

Our house was what New Orleanians call camelback shotgun: narrow and running horizontal with no hallway, and with a second floor of only one room added onto the back, the kind of house old folks say spirits like because they can move through easily. There were no doors separating rooms, so my seamstress mom put up curtains that fluttered or fell as we kids ran through. Mom’s room was separated from the kitchen by a pink woolen blanket that we badly needed on our beds during wintertime when the collective drafts had us gathered around the oven. Someone always walked away with a burnt leg from trying to get too close to the heat.

My Creole mother raised her children with flair. She herself was raised by my grandmother Amelia, who, even once she got Alzheimer’s and couldn’t remember my name, still held a fork with her pinkie finger extended out and to the side in the way of a queen. Amelia taught us to move about with stride, to do whatever it was we wanted to do, to pack mental lunches wherever it was we were going.

My mom had taste. She grew up on Roman Street, uptown, and seemed obsessed with other people’s houses. Not the grand St. Charles Avenue of New Orleans, but the simple and clean homes. Those across the highway, even, on the other side of Wilson, where the houses were mostly brick. But she bought our house with $3,200 in cash in 1961. And that stood for something.

Mom loves pretty things. She crocheted gorgeous, marigold-colored blankets for the girls’ twin beds, and concerned herself with the particulars of how we looked when we left the house. She sewed most all of our clothes so perfectly that no one could tell they were homemade. She planted vibrant gardens outside our house, and she demanded we stay out of the living room, with its champagne-colored settee trimmed with dark wood carvings, its gold candelabras, its gold and faux-crystal chandelier, and its French windows that opened out. My grandmother made a white ceramic statue of one of our cats, Persia, which sat on the floor beside two tables with harp-shaped bases that were hell to polish. If we happened to have a visitor, like, say, the insurance man, this would be where he’d wait. But even with this one good room, none of our friends could come over.

We understood this through subtlety, my mother’s way. “You know this house not all that comfortable,” is how she might say it. And so you asked once, twice if you were hardheaded, then never again.

My dad had never finished the upstairs that was the boys’ room, so there were still wall bearings instead of wall to stare into. “Your daddy didn’t want to spend the money to do things right,” my mother would say. “Instead of taking up the kitchen floor if it had a hole in it, like anybody with sense, he’d just take boards and put over the hole so one part be up all crazy-like and so you’d be walking up and down across the floor.

That’s how things were fixed when Dad was alive. Once he died, when I was six months old, things continued on in that way, or not at all. The small bathroom where Mom discovered Dad on the toilet after his brain aneurysm in June 1980 seemed to fold in on itself: Its dark blue painted walls peeling; the socket hanging from the wall with pieces of electrical tape showing; the sink collapsing.

“A house has to be maintained,” says my brother Simon now, after the fact, but back then when he was in the Army, the house felt like falling apart and the older children didn’t fix it back up. My brother Eddie left for marriage. Another brother found drugs. Others were running after women or seeking work in order to get them. And then it was just five daughters, and Byron, the youngest boy.

My sister Karen’s amateur-carpenter boyfriend once tried putting a brown tribal-patterned linoleum on the kitchen floor, but the corners started curling a few years too soon. One minute you’d be walking around barefoot and gliding on the linoleum mom had polished, then two steps later suddenly felt yourself walking on the wood patches where the linoleum had come up. In due time, the floor got to be so holey that rats had easier access to bread than at any other house on the block. When I was a small girl playing hopscotch, Oak Haven trailer park had been right next door, separated from us by a fence. Mom says the rats came to live with us when those trailers were knocked down. However they came, they did, and enough of them to make so much noise in the next room while you were trying to read James Baldwin or sleep that you didn’t dare get up out of bed to see what they were doing. You’d know in the morning, anyway.

Karen’s boyfriend also built a kitchen cabinet but never got around to making its doors. Mom ended up making curtains. She did the best she could: white linen on the bottoms; fruit-themed valances on the tops. “I like things nice,” she will say.

This same boyfriend tore down the den walls to redo the paneling, but then he and my sister broke up, so that the room where the family watched the Saints lose football games closed down, too, becoming a storage room that leaked rain.

The plumbing was never right. We had buckets underneath the kitchen sink catching dishwater. The kitchen cabinets had big holes that led to the outside, which Mom patched up with foil after hearing somewhere that rats couldn’t chew through it. They did.

The bathroom near the rear of the house was the only room with a lock. I took full advantage of that, especially when I wanted to get away from my older brother Troy, whose nerves were always bad. He had a pointy ear and I fixated on it. The more his leg shook when he sat, the madder you could get him. At those moments, I’d yell “Ear, ear, ear!” to rile him up, and sure enough, he (a grown man) would chase me (eight or nine) through the house. I’d lock myself in the bathroom, and since he’d wait a long time for me, yelling, “Wait till you come out, lil gawl,” I memorized its insides. I learned right then and there the geography of hiding.

The faucets on the bathtub broke after we started using pliers to turn the water on and off. When this happened, we’d have to boil water on the kitchen stove and carry it through the bedroom and into the bath, saying, “Watch out, watch out now,” as warning.

Some nights we’d return home to find termites, or flying cockroaches, gathered in our rooms and I’d stay up nearly the whole night watching them fly, crawl, and fly.

To describe the house fully in its coming-apart feels maddening, like trying to pinpoint the one thing that ruins a person’s personality.

Years ago, in childhood, when friends asked if they could drop me home from school, I’d go into a panic thinking maybe then they’d want to come in and use the bathroom. I’d rather walk, or take the bus even in sopping rain. If someone insisted on giving me a ride, I’d lie about needing to go to the grocery store so I could be dropped off at the corner instead of in front of the house.

I lost my best high-school friend, Tiffany Cage, who couldn’t understand why she was never invited over when I was at her apartment at least once a week. Her place wasn’t lavish, but it wasn’t falling apart either. When she started demanding visits, I’d lie: You will come or We have company now or You will come.

I just did not know how to be true about it yet.

Lynette, the makeup artist, and my closest sister in age, avoided having a slumber party for so long that she also lost a playmate, Kristie Lee. Thirty years after the fact, Lynette says: “I knew what would happen if you made friends. So I stopped making them. It meant that people were going to want to come into your life, and they weren’t gonna come nowhere near that house. Not even if it took everything in me.”

So there was this house that I belonged to, and then there was me with my loud personality and private-school training. I’d been pulled from public school after I began cutting classes out of boredom. Tuition at the private school was more than my nurse-aid mother could afford, but we paid in bits and pieces.

Mom dropped me off mornings in our white Chevy Nova, and I remember never wanting her to get too close to the archway of campus. “Just let me out here” is what I’d say the moment we entered the parking lot.

Once school let out, the return home was always more painful than the initial leaving. Just like now.

The school bus would drop me off on the long side of Wilson Avenue. Returning to the yellow house meant having to walk a ways before arriving and on the way a great many number of things might happen. Many of them were fun but then there were those times I passed by parked police cars and saw women’s heads bobbing up and down in the driver’s seat and knew exactly what was going on, and then was taken with the wonder of that and the question of why we were living in a city where police took lunch breaks in such peculiar ways. This feels like telling on my city, but it is true. Then at the corner of Chef Menteur and Wilson I’d wait on the neutral ground (as New Orleanians call median) in my red-and-gray uniform skirt, white button-down shirt, and burgundy vest, before crossing over to walk the fifty or so steps home.

Home: Where I was only called by my French middle name, Monique. On my very first day of school, Mom pulled me aside, and instructed me thus: “When those people ask your name, be sure to tell them Sarah. Never Monique.” And so I did. And still I do. I went by my proper name, Sarah, outside the house. When classmates called asking for Sarah, my fisherman brother Carl said, “Who that?” Sarah and Monique, such different titles, in sound, in length, in feel. I’ve got to let you know this because I have felt for so long that those two names did not like each other, that each had conspired somehow against the other. That the classified, proper one told the raw, lots-of-space-to-move-around-in one that it was better than she. And to this day, no one within my family calls me Sarah, unless they are making fun.

Home: Where Mom taught us to clean maniacally so that even in the falling-down house, she was always mopping floors using ammonia and bleach (which she calls Sure-Clean, no matter the brand), taping things together, trying to make everything presentable. “You’ve got to make whatever place you live in look decent” is what she’d say as I stood in my plaid skirt watching her. The house seemed like the biggest, rowdiest child, with Mom always bent trying to clean it, to dress it well. And yet she hadn’t strength enough. The house kept falling down around us.

When I went back to New Orleans the first time, thirty-five days past the storm, there were birds living in my childhood home. So that when I approached it, with its broken-out windows, they flew away en masse. It was a flurry of flight—like the scrambling of overweight thieves at the sound of gunfire.

The house looked as though a furious and mighty man crouching underneath had lifted it from the foundation and thrown it slightly left, off base. And once he’d done that, it was like he’d gone inside, to my lavender-walled bedroom, extended both arms, and pressed outward until the walls expanded, buckled, and then folded back inside themselves.

The house had split in half. And the yellow siding that cost in the thousands of dollars, and which Mom paid for over seventy-two months, where it had not blown away, was suspended like icicles.

The front door was wide open; a skinny tree had angled its way inside. I entered the living room and took baby steps forward, afraid the weight of me might collapse it. The farthest I went was into the middle of the living room. It was all dust, wood chips, waterlines, but then also the light switch by the front door. Cream-colored with gold script around the edges. Pretty.

Somehow the house just looked more like itself. It was really so small. And sitting there all curvy-looking. I knew right then that it had fallen so that something in me could open up.

For so long, I have held that yellow house inside me. I have been at times shaken when it came to letting people near me because it would mean letting them near the unadulterated one, the real yellow house. I was a kid raised well (with class and hope but little money) and who grew up in a raggedy house. I never did need to be one or the other. I mean, who does not know that they are more than just a single adjective? But back then when I was eight, twelve, fifteen, I had no idea about the stupefying nature of dichotomy.

Or that, if one is able, one might, one day, return to stand facing everything you originally left looking for.

Mom is living now in Saint Rose, Louisiana, but recently visited me in Harlem. We three: My sister Lynette, Mom, and I went to the Metropolitan Museum of Art to glimpse the “After the Flood” exhibit. As I slowly made my way around the bend, Mom said, “Got a picture down there make you think of the old house.” I wanted to run and see, but did not.

Eventually, I stood facing the image. The color, yes, like our house, except that it was wider and the innards were spilling out. The yellow house always kept its dilapidation secret, lest the Broom clan’s business be all over the streets.

Back home, I researched the demolition of our house and found an article from the New Orleans Times-Picayune headlined: RED DANGER LIST: 1,975 PROPERTIES DEEMED “IN IMMINENT DANGER OF COLLAPSE.” I scrolled down fifty-one pages before seeing it: 4121 Wilson Avenue, New Orleans, 70126, our old address.

Yellow House, I wonder how you felt to be bursting open, at last, your secrets out, proclaimed, free, falling this way and that, at least momentarily, before being obliterated, swept into flying dust. Gone.

Sarah M. Broom will open our South Words reading series on October 15, 2019. Reserve your tickets here.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.