St. Cassius

Canonizing an American Radical

GOAT (Greatest of All Time), edited by Ovais Naqvi and Helmut Sorge, Taschen Books

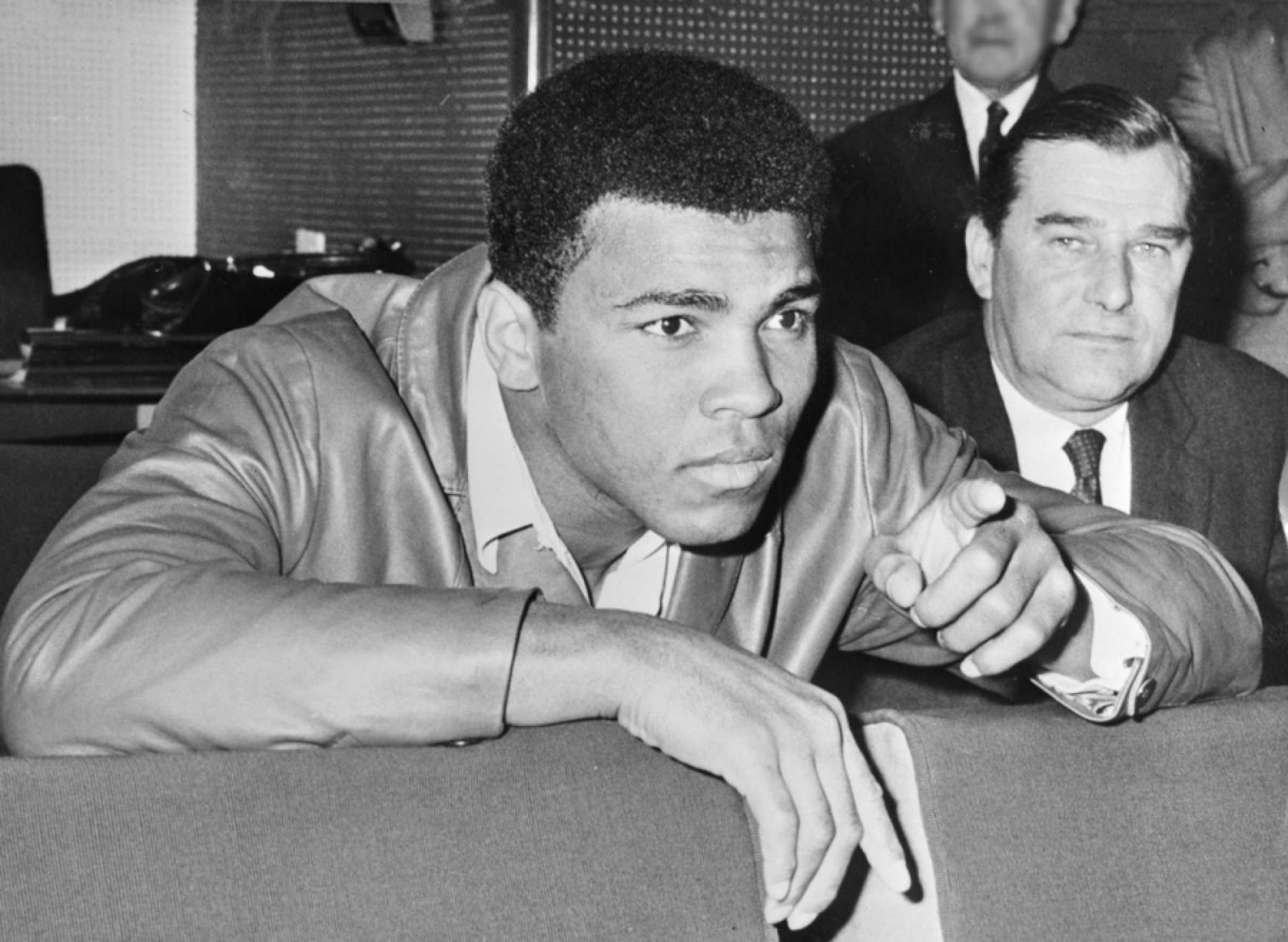

It’s been said that more has been written about Muhammad Ali than about Abraham Lincoln, Jesus Christ, and Napoleon, a claim that’s difficult to prove, but which suggests a truth: the media dedicated to Ali—books, articles, photographs, films, music, and various ephemera—is staggering. The attraction, of course, is to a life that seems improbably epic: A kid from Louisville, Kentucky, wins Olympic gold in Rome, becomes boxing’s heavyweight champion and a Civil Rights revolutionary; is excommunicated from boxing for refusing the Vietnam draft; spends his physical prime appealing a prison sentence; is redeemed by the public’s outrage over the war; fights again, and reclaims the title stripped from him; reigns thrillingly; is eventually humiliated by a former pupil; and ultimately reinvents himself as a prince of peace. This is a crazy, tough American fable to beat, or even resist, and so Ali remains a literary temptation, what Wilfred Sheed described as “one of those madonnas you want to paint at least once in your life.” Books on him are about as common as translations of Homer, and as consistent. Interpretations might pale, but the deeds remain undiminished.

The pace of Ali’s hero-worship continues. Since the summer, several books about him have been published, including a pocket reference book called The Rough Guide to Muhammad Ali; a collection of photographs published by Harry N. Abrams, Muhammad Ali: By Magnum Photographers; and his own collaboration with his daughter Hana Ali, a book of spiritual musings titled The Soul of a Butterfly. Never mind his cameos elsewhere, in both books and on television. Also, this past October marked the thirtieth anniversary of his comeback victory in Zaire against colossus George Foreman, a fight that thrust Ali straight into the mythic. ESPN Classic was relentlessly nostalgic that week, even teaming up with 60 Minutes to air a special show for the occasion.

This obsession with recent history begs simple questions: At what point does the fable risk overkill? What can yet another Ali biography possibly contribute to our understanding of him? Moreover, how does a publisher distinguish its book from the tonnage of material that already exists?

Scale, perhaps—a signature physical trait of a few books by the publisher Benedikt Taschen, who through scale and scope has attempted to “turn the logic of the biography on its head.” The result is GOAT (Greatest of All Time), a biographical atlas of the fighter’s life. It is a very big book, measuring 20 x 20 inches, 792 pages that stack eight inches thick, the whole thing weighing seventy-five pounds. It contains over three thousand photographs—printed in eight-color format on semi-matte paper, with a gloss varnish on each image—and is the most comprehensive archive of Ali’s two most notable photographers, Howard Bingham and Neil Leifer. But it isn’t just a collection of photojournalism; the text—essays, interviews, newspaper reports—runs at about half a million words. It took four years and $12 million to produce, with a print run of only 10,000 copies priced at either $3,000 or $10,000, depending on which of the 10,000 copies you want—whether it comes in a white, silk cover, whether it comes with four framed Bingham prints, and whether you want the inflatable sculpture by Jeff Koons to come with it. The odds of you actually getting your hands on this book are not good; it’s more a grail to be sought out at some gallery or rare-book room by fans willing to make the pilgrimage to see it, provided such institutions can afford the thing.

Big gestures distinguish the Taschen press, which earned its reputation in the early ’80s by putting out affordable art books, then moving on to establish a deep catalogue of practical paperbacks and more lavish coffee-table books on art, architecture, and popular culture. Taschen’s range stretches from the academic to the weird, with such titles as New Objectivity (“Realist Trends in German art of the 20s”), the ubiquitous 1000 Chairs, and the freakish, erotic Modern Amazons. Taschen’s extravagance peaked in 1996 with the publication of SUMO, a retrospective of the photography of Helmut Newton, the largest bound book (20 x 27.5 inches) of the twentieth century. Recently sold at auction for $304,000, it is among the century’s most expensive.

GOAT follows SUMO in spirit, but is more historically and culturally ambitious. It is also physically demanding. Healthy children under the age of nine weigh less; one must lean over like a monk to read it. The pleasure, and work, is in committing to a book of such proportion. Because of its size and quality of production, the reading experience feels more cinematic than literary. Images cut a clean, symmetrical path through white pages of four-column text, and when the narrative arrives at fight night, the pages fade to black, the text subsides, the theater lights dim. The fight pictures are like car crashes in slow motion—violent, vivid. You can count the beads of sweat flying off Ken Norton’s head, measure closely how contorted a face gets when a fist’s in it, see just how garish the cut above Henry Cooper’s eye really was (like struck with buckshot). Intense images of this size trigger a slight loss of balance, like wading in the image, the periphery crowded out, especially with several wide-angle shots taken from above the ring. A few of these overhead shots happen to be good studies in atmosphere. The 1972 fight with Bob Foster, for instance, at Nevada’s Sahara Tahoe Casino, was a gross mismatch (Foster weighed forty-one pounds less than Ali), and drew a crowd of just under two thousand. In the bird’s-eye view of this fight, Foster is crumpled on the canvas, the match all but over, and the audience, tucked tightly into orange banquets, looks bored. Cocktail glasses sit half-empty. A few couples ignore the fight altogether. The dinner theater seating adds a cynical aspect to the scene, reminding us that boxing is, as much as anything else, simple, brutal entertainment. What other profession sanctions pummeling in front of dinner tables? At a casino? Under a disco ball? Soon into GOAT, you realize what a miserable way this is to make a living.

Ali spent twenty-one years as a fighter, between 1960 and 1981, and the best fight images from that time work as counterpoint. His brashly promised defeat of Sonny Liston in 1964 made him champion, and their rematch a year later provided his most iconographic fight image, a violent pietà: Ali looming over Liston, who buckled in the first round, demanding furiously of him: “Get up and fight, sucker!” The complement to this moment comes with Ali’s first defeat, in the “Fight of the Century” against Joe Frazier (1971), in the echo of Frazier’s left hook: Ali tilting backward, his legs crooked and useless, his face wearing a cancelled look. Other images, other moments, connect this way: Liston staring from his stool (1964), mentally zapped, ignoring the bell for the seventh round, inaugurating Ali’s wild career as champion, countered by Ali slouched on his own stool in the fight against Larry Holmes (1980), a fight widely dreaded (Ali, thirty-eight, was already showing signs of damage in his slurred speech). Ali looks so bruised and zombie-like in this photo, it seems doctored. He would fight once more after this, but against Holmes the door was basically shut.

Photographs of Ali’s fights are innumerable, many of them hypnotic, but the images of him in more common circumstances are what both humanized and beatified him: meditative at training camp in Deer Lake, Pennsylvania, or clowning on a Louisville sidewalk, or talking easily with a gaggle of children in his front yard in Miami. (Children were his most natural audience, his mind channeling a childlike, impudent brilliance.) Documenting these moments required not only access, but sensitivity, and Howard Bingham, the photographer whom he’d met in 1962, and who quickly became his closest friend, possessed an instinct and timing that allowed for unintrusive intimacy, a talent Gordon Parks said allowed him to explore Ali’s geography “with the sensitivity of a blind man.” Both Ali and Bingham were famously generous men. Bingham often helped other photographers gain access to the fighter, while Ali himself would devote as much time to high-school reporters as he would to writers from Sports Illustrated or the New York Times.

Then again, Ali was addicted to attention. When he drove his bus to Denver to sneak up on Liston’s home in the middle of the night, he called the local papers just ahead of time—and there they are in a famous midnight snapshot: Ali’s small entourage, including Bingham, looking like a high-school posse out to toilet-paper the class geek’s yard. Another time, he convinced Life photographer Flip Schulke that the secret to his hand speed was that he trained underwater, and Schulke’s photo session of this fake swimming-pool workout all but baptized the fighter as a sex symbol. More lowbrow publicity efforts include sparring with a man in a gorilla suit, and strolling along train tracks, swinging a bear collar, hunting Sonny Liston, the “big ugly bear.”

No media darling could have wished for better timing, since television both improved and expanded dramatically during Ali’s career. He reaped the benefits of the trend. One could even say he was technologically star-crossed. His physicality translated nicely from the trembling black-and-white newsreels and smeared gray broadcasts of early television to the live color broadcasts thereafter. His good looks were consistent over time (he was always clean-shaven, and rarely suffered cuts). Poorly educated, his wit and verse were nonetheless soundbite ready. The articles on him were provocative, and the photographs magnetic, but television was his main conduit to the imagination. It transmitted his great psychological talent, which was doubleedged: to seduce and intimidate, entertain and damage (the cruelest example of which was when he cast Joe Frazier, a South Carolina sharecropper’s son, and a “blacker” man than Ali ever was, as an “Uncle Tom,” which the public indulged).

And while television showcased his bombastic persona, closed-circuit theater broadcasts amplified his physical effect—a man 6' 3" dancing lightfooted and snapping heads back with hands so fast, as Richard Pryor joked, “You don’t see his punches till they comin’ back.” Technology distinguished Ali’s victories. Consider Jack Johnson’s knockout of Tommy Burns in 1908 to win the heavyweight title, how the news trickled back from Australia via telegram (films of Johnson were banned in certain states, footage of him knocking out white opponents deleted altogether). Even Joe Louis’s fights, broadcast mostly by radio, depended on the imagination. In Shadow Box, George Plimpton recounts a story told to him by Drew “Bundini” Brown, Ali’s shaman-like cornerman, who described how folks in Sanford, Florida, would listen to Joe Louis’s fights by stringing amplifiers along the pines. During fights, Plimpton writes, they “sat around in the darkness to listen and cheer, and [Bundini] remembered that a storm was whipping the pine forest during one of the broadcasts, so the words from Madison Square Garden, or wherever, were shredded away, people running around in the wild darkness trying to find out what was going on as if the words whirling off were corporeal, retrievable, like panicky chickens.” By the time Ali peaked, his victories were broadcast globally and in living color, in real time. Watching him on theater screens indulged the senses. When he fought George Foreman in 1974’s “Rumble in the Jungle” in Kinshasa, Zaire, for the heavyweight title, they entered the ring at 4 A.M. in order to accommodate the closed-circuit audiences in the U.S. Ali was again an underdog, as he was with Liston, but by then an international hero for his anti-war position, especially in third-world cultures. A sweet, tragic worry preceded him into the fight, since many thought Foreman would destroy him, literally. This premonition, coupled with the beating he took for his “rope-a-dope” tactic, cranked up so much tension that when Ali finally knocked Foreman out, a shock of ecstasy shot through hundreds of thousands of people at once. They saw Foreman drop. And as the crowd of sixty thousand in Kinshasa’s 20th of May Stadium chanted Ali’s name—in a monsoon that broke just as the fight ended—the full house of closed-circuit viewers in New York’s Madison Square Garden spilled out onto Seventh Avenue, some jumping on top of cars, and began chanting it too, there in Manhattan’s streets. Who knows in how many countries Ali’s name was being chanted then? Strange, too, that his name has a universal cadence.

If Ali was a cultural curiosity for writers before 1974, he was a literary fixture afterward. That fight in Zaire marked his zenith and rounded out his character. Nobility and genius were added to an already loaded gun. He’d been a pariah, a touchstone, and by the time he fought Joe Frazier in the “Fight of the Century” (1971), a cause célèbre (the fight was such a hot ticket that Frank Sinatra worked that night as a photographer for Life magazine). But the “Rumble in the Jungle” with Foreman expanded Ali’s metaphorical qualities. Instead of closure, it shot his narrative forward.

The subject of Ali has attracted writers seemingly distant from sports—Alex Haley, Joyce Carol Oates, Gary Wills, and Ishmael Reed—because he, along with boxing, has antecedents in so many aspects of American (and ancient) culture. Well beyond the trajectory of sportswriting, he’s inspired some bright, essayistic interpretation. Unfortunately, some of this heady stuff is not included in GOAT—not Oates, nor Reed, nor A.B. Giamatti, all of whom improvise brilliantly on the fighter’s cultural impact and are included in Gerald Early’s Muhammad Ali Reader (1998), a source GOAT’s editors could have tapped.

GOAT does lean heavily on the traditional Ali canon, drawing from such excellent sources as Mark Kram’s pieces for Sports Illustrated; David Remnick’s 1998 book King of the World; and especially from the interviews that make up Thomas Hauser’s definitive oral biography, Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times, in which the participants (over a hundred and fifty) provide a candid portrait of the fighter, his entourage, and the profession. Norman Mailer and George Plimpton dominate GOAT’s middle chapters, “The Once and Future King” and “House of Shock,” which cover Ali between the “Fight of the Century” and the “Rumble in the Jungle.” Plimpton and Mailer make a good pair of portraitists—two singular minds with radically different but equally entertaining approaches to sports journalism.1

GOAT also includes original essays and interviews, mostly sentimental, especially toward the book’s end, giving it an eerie sense of closure (Ali turns only sixty-three this January). A few entries balance out this sentimentalism. Mark Kram’s writing from Esquire and from his book Ghosts of Manila provides a sobering account of Ali’s awkward, depressing transition into retirement as his Parkinson’s syndrome—the direct result of so much physical punishment—clamped down on him. Thomas Hauser’s essay, a retrospective of Ali’s iconic evolution, is particularly good for the cold water it throws on the sanitizing forces that have lately propelled the retired fighter’s image. Hauser homes in on Michael Mann’s biopic, Ali, for its oversimplification of Ali’s Muslim faith, and for watering down the cruelty he practiced on Frazier (GOAT includes, by the way, not only examples of Ali’s hurtful barbs against his black opponents, including Frazier, but an amazing transcript of a conversation Ali recorded one afternoon while he and Frazier cruised around Harlem, in which Ali seems remarkably congenial, almost avuncular).

These critical assessments don’t contaminate the reverent spirit of the book; rather, they remind us that Ali’s greatness evolved out of controversy, out of a cultural and political trial-by-fire. Hauser scorns the revisionist effort by corporations (and, to some degree, by Ali himself) that have sought to capitalize on the boxer’s status as a celebrity-saint. This commodification— which began soon after he lit the Olympic torch in Atlanta in 1996—is a serious threat, Hauser argues, because it distorts, and therefore denies, the historical context of Ali’s influence. So while it may be only marginally important to recognize Ali’s weaknesses with women, with hangers-on who duped him, and with money, it’s critically important to know that his fame evolved first out of infamy. When Ali shouted “I’m pretty!” in 1964 during the ringside interview after beating Sonny Liston, it was a defiant statement, and had everything to do with race in America at the time. When this proud, young black man—one who predicted, almost supernaturally, when his opponents would fall, who rallied behind his own supremacy, who belonged to the separatist Nation of Islam, a sect that perceived whites as “the devil”—howled “I’m pretty!” it wasn’t just funny, or even comically arrogant. Its undercurrent was cutting, a precursor to what he would tell the Black Scholar about his refusal to be drafted: “I was determined to be one nigger that the white man didn’t get. One nigger, that you didn’t get, white man. You understand? One nigger, you ain’t going to get. One nigger you ain’t going to get.”

If this bold rhetoric seems foreign to Ali’s admirers, then Hauser’s warnings should be taken to heart. The truth is that Ali’s transition into diplomacy was slow and awkward. After a rough experiment on behalf of the Carter administration, clumsily defending the U.S. boycott of the 1980 Olympics after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, Ali found his bearing, and went on to lead several humanitarian missions, including the delivery of medical supplies to Cuba, traveling to Vietnam in 1994 in search of MIAs, negotiating a prisoner exchange between Iran and Iraq, and even negotiating the release of hostages from Iraq (following a parade of envoys that included former heads of state, members of parliaments, and even Jesse Jackson) just prior to the Gulf War. Today he is perhaps the most sympathetic figure in world affairs, in part because his physical deterioration reminds us of his once-celebrated physical prowess. Seeing him in this condition triggers unavoidable emotions. And if this irony causes people to love him more than they would otherwise—and leads somehow to some kind of global harmony—so be it. The risk to history, perhaps, lies in being selective about how Ali is remembered. His utility as ambassador now goes hand-in-hand with his ubiquity as a corporate symbol—Wheaties, Coca-Cola, Apple Computers, Chevrolet—the latest of which is Adidas’ “Impossible is Nothing” campaign. This kind of branding—this rate of branding—requires whitewashing, and this is the danger Hauser warns us about.

If GOAT were the last contribution to Ali’s great legacy, it would be more than most presidents get. It vividly explores the connection between the fighter and the American zeitgeist of the 1960s and ’70s, and is, in the end, an impressive, almost overwhelming biography.

But who will read it? Ten thousand people, give or take a few. Of course, there’s plenty of material out there, but who among the last two generations is even interested? Ali’s fans, of course. Maybe Mailer’s fans. Or Plimpton’s. Or the most literate of boxing fans, maybe. Exponentially more people will learn about Ali though merchandising, and through a forthcoming source—the most ambitious Ali project yet, and it warrants some consideration here.

Next fall, in a kind of homecoming, the Muhammad Ali Center, an “international cultural and educational institution,” will open in downtown Louisville, on the banks of the Ohio River. Whatever its humanitarian or spiritual goals, there is no question who the wellspring is: A forty-foot mosaic of Ali will wrap around the building’s facade (something creepily totalitarian and mesmerizing about it, as bold as anything Stalin slapped on a wall), and a majority of the square footage will be dedicated to interactive-media displays that showcase Ali’s life as a fighter, as a way of teaching six pillars of virtue: respect, confidence, dedication, conviction, giving, and spirituality. If it begins to resemble a temple, perhaps it’s no coincidence. Even in design, not yet built, the project seems to border on off-the-radar adulation. But that same energy might be what makes the Center work. The greater the distance between us and history, the harder the lesson is to burn into the brain. With Ali, his best effect is emotional, and perhaps this temple, with its variety and dazzle, is the most effective way to inspire a generation born well after his retirement. The risk, if there is one, is to history—if it’s enlisted to promote the individual, as opposed to the individual being our guide to understanding history.

As tributes go, the Center eclipses GOAT by a long shot. But will it be as balanced? And what exactly is the value of a great man’s past? Can Ali’s biography be a form of public service? Can it improve the world, no matter how slowly? More than twenty years away from the ring, as much time as he spent in it, his legacy will be tested by the pressures of nostalgia.

All but muted, his ego intact, Ali defers to technology, to media, to speak for him. His coda—one version of it, at least—will inevitably be written by someone he will have indirectly influenced, some loner kid he’ll likely never meet, who will have read about him in a book, or seen a movie—or, bored one afternoon in Louisville, will find himself ogling some bright multimedia showcase of a fighter in his prime—a funny, scary revolutionary who was also, for some reason, very sweet to people. Children loved him. After a while, a whole lot of people loved him. Now, it seems, everybody loves him. You risk sounding cynical if you question this trend too deeply. But for those who have faded from the church, perhaps this kind of worship is the perfect ersatz religion, and Ali the perfect ersatz prophet. And why not? Chances are the loner kid will leave the temple inspired. Not jumping on top of cars, necessarily, but at least a little fired-up, walking a little taller.