"World Books," altered set of encyclopedias, by Brian Dettmer. Courtesy the artist.

Search History

By Allison Braden

As a YMCA yoga class wrapped up in the early 2000s, conversation turned to cockroaches. They’re difficult to escape in the humid, marshy suburbs of Savannah, Georgia. So when one woman mentioned that she hadn’t seen one in her house for more than ten years, the others, including my mother, wondered how it was possible. There’s a recipe, she said as she rolled up her mat, and there’s only one way to get it: Go to the public library on Bull Street and ask the reference librarian.

My mom knew exactly where to go. A white, baby boomer professor, she’s accustomed to seeking out information at libraries. Though we had our own small library branch in the middle-class suburbs of Wilmington Island, she often took my sister and me to Bull Street. Overlaid in white Georgia marble and fronted with towering Ionic columns, Savannah’s flagship library was to us a solemn bastion of literacy and learning. Soon after the yoga class, Mom swung by the history and genealogy room and asked about the roach recipe. After a moment of confusion, the reference librarian, Sharen Lee, told her about the FAQ boxes.

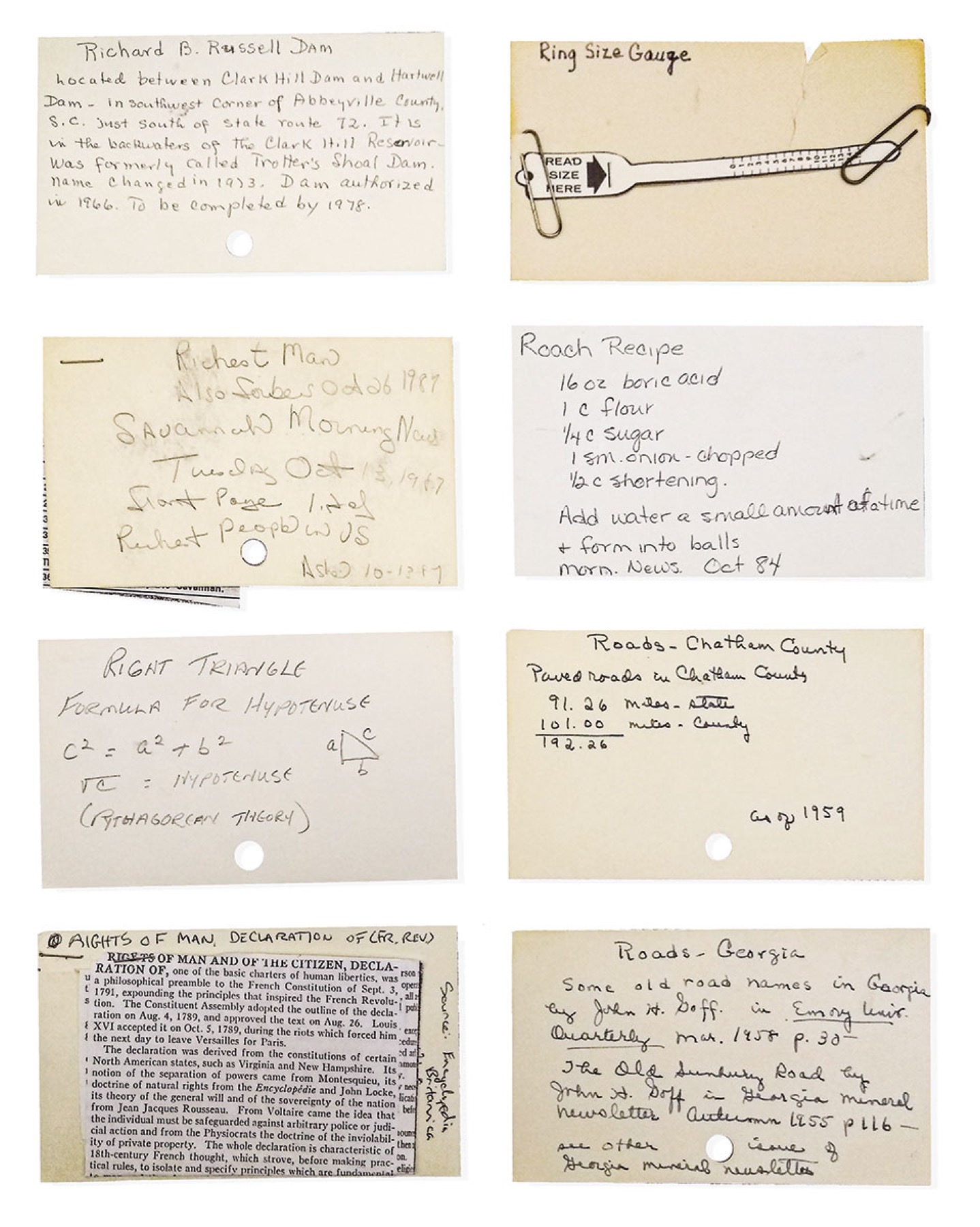

Handwritten on an index card, the recipe turned out to be part of an ad hoc collection of local history, general trivia, and helpful know-how. Arranged in alphabetical order by subject, hundreds of similar cards fill a trio of long orange boxes. They contain the answers to decades of questions from library patrons, and they illustrate a vanishing way of transmitting and stewarding local culture. But regional distinction hinges on knowledge that is by definition not universal, and from the cards that are in the FAQ boxes—and those that aren’t—the South’s familiar fissures emerge. In the fall of 2017, more than a decade after she found the roach recipe, my mom mentioned this curious repository by chance. Lured from my home in Charlotte, North Carolina, by the prospect of “secret” Southern knowledge and long-forgotten lore, I arranged with Lee, on the cusp of retirement after twenty-eight years at the library, to see the boxes.

I had never had reason to visit the library’s genealogy room. When I was a preteen in the early 2000s, even as I was checking out thirty books at a time, I learned that if I had a reference question, I didn’t need to ask a librarian—I could just Ask Jeeves. In dedicated computer classes at school, we clocked our words-per-minute typing and learned to search for information online. By then, flipping through dictionaries and referring to encyclopedia entries already felt quaintly archaic.

My generation was at the vanguard of a fundamental shift in our relationship with information. We now rely on Google so much that scientists suspect our memory has morphed. In a 2011 study published in Science, a team of cognitive researchers wrote, “The internet has become a primary form of external or transactive memory, where information is stored collectively outside ourselves.” We don’t know the material. We know where to find it.

It had been nearly a decade since I’d visited the Bull Street library, but nearly every room and floor held memories: I’d browsed picture books and graduated to chapter books in the colorful children’s area, then climbed the stairs to check out adult novels and do research for school projects. The metal racks on the third floor fed my nascent obsession with magazines. But Sharen Lee, who spoke in a librarian’s low tones and walked with a cane, led me through a nondescript door on the second floor into a room I’d never visited. I felt privileged, welcomed into the heart of what I considered a sacred institution, but the prosaic reality was a row of cubicles converted into storage. Clinical fluorescent light illuminated haphazard stacks of loose papers and plastic storage boxes. She found the bin she was looking for—nothing marked it as anything special—and mentioned that she hadn’t referred to the FAQ boxes in years. With the internet, there was no need. But at one time, she told me, these slender orange boxes were considered the most important item in the library.

In 1990, when she was applying for a job in the department, Lee’s interviewers explained the story of the boxes and why they were so valuable. At some point, likely during the 1960s, the reference librarians began to compile the answers to frequently asked questions (the area and population of Savannah, for example, or how to say happy birthday in several languages). They jotted each answer on an index card, usually along with a source, though not often with a date. Sometimes, patrons—journalists, historians, schoolchildren—wanted information that proved hard to find but might be asked for again. The librarians stuck those answers in the box, too. “It saved us a lot of extra work,” Lee says.

Over the next four decades, the collection grew. Most of the cards are handwritten, often in neat cursive. Some are typewritten. Others are paperclipped to faded photocopies or ochre newsprint. Nearly all are topped with a single word or phrase—Babe Ruth, Bulldogs, Cherokee alphabet—to help the librarians locate the right card, but the boxes’ ad hoc nature suggests that institutional knowledge played a role, too: The librarians may not have known what was on the cards, but they knew how to find it. Though they would eventually hold hundreds of cards, the boxes remained a small part of a vast library. Opened in 1916, the main library is home to maps, telephone books, newspaper archives, Civil War and colonial records, fragile historical and genealogical documents, and a huge portion of the library system’s collection of 788,964 books. But Lee’s interviewers were unequivocal: In the event of fire or flood, save these boxes first.

Lee set me up at a table in the intimate genealogy room, in the shadow of hand-crank shelves and a small balcony. In the second box—H through R—I found the roach recipe. Was it true that these boxes, as my mother’s fellow yogi said, were the only place you could find it? Of course not. The card itself cites an October 1984 issue of the Savannah Morning News as the source of the pantry-ingredient insecticide. A quick Google search for “boric acid roach balls” turns up more than 150,000 results. But that didn’t lessen the recipe’s charm. I pulled out card after card. Most, if not all, held information I could easily turn up online—the definition of ayatollah, the traditional gifts for every anniversary—but each tidbit nevertheless provoked a multifaceted, kaleidoscopic delight.

First, there was the sheer novelty. This is how people used to find and transmit information? Each card implied an interaction and an idiosyncrasy that infused the boxes with more personality than Google’s list of links. Each card was the artifact of a curious impulse. The answers, divorced from context, raised questions of their own: Who wanted this information? And why? What brought them to the library? Was this request made once or a hundred times?

I could link a few cards to current events, from the Iran hostage crisis to the emergence of AIDS and the internet. In some cases, narratives suggested themselves: One card said that in 1974 more than ten percent of the local population was illiterate. Another card pointed to a resource for calculating the cost of attending college, while another had only a handwritten 1-800 number for Georgia’s HOPE scholarship program, which covers tuition at in-state schools for qualifying students. From these sparse facts, I could conjure a story of an ambitious youth turning to the library to break a cycle of poverty through that great American ideal: education.

My fanciful vision unwittingly reflected one of the founding missions of this country’s public libraries. Library science researcher Michael Harris notes in The Role of the Public Library in American Life that George Ticknor, who helped found the Boston Public Library in 1848, envisioned it as a place where immigrants could familiarize themselves with American citizenship and institutions. The mission was Janus-faced, designed to create one cultural identity—and erase others. It would be a site of assimilation, where librarians would encourage the masses to better themselves through moral and intellectual education. At the library, patrons would learn to fit in.

The cards gave me a sense of belonging, too, with their aura of secrecy and the cachet of privileged local knowledge. I felt as though I were turning the pages of my hometown’s faded diary, or scanning its online search history, as vulnerable and telling as any of ours. Like the internet, strangely enough, the FAQ boxes were another kind of external, collective memory. I found reflected in the cards the Savannah I knew, a port city that was nonetheless insular, home to a college full of avant-garde art students yet still stubbornly bound to tradition and status. I also discovered a town that I, a first-generation Savannahian, didn’t know. The cards hinted at lore passed from fathers to sons, recipes passed from mothers to daughters. They insinuated the kind of knowledge that made one truly native to this place, like the families that can trace their local ancestry back twelve or more generations.

I resolved to return to the library and photograph all the cards, a task that felt strangely urgent. I feared that the boxes, obsolete and relegated to a back room, would disappear if I turned my back too long. I wasn’t desperate to hang on to the long-dead phone numbers or outdated statistics; I wanted to grasp their ineluctable glimmer, some mysterious quality of information that disappeared when we Googlified our minds. I visited the library again in 2020 in the midst of COVID. The stacks were nearly empty of people, the pandemic having hastened this and all libraries’ pivot to digital resources and collections. As I took picture after picture, I realized the cards spoke to a much bigger search than any one of the long-ago queries: the search for identity.

In the FAQ cards, I found an alluring alternative: knowledge that rooted me deeper in a sense of home.

Cards from the catalog. Courtesy the author.

In its mission to “organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful,” Google commodifies and optimizes results, which threatens to erase regional differences and peculiarities. Search for a biscuit recipe and you’ll find the highest rated, the most popular. You’re unlikely to discover the old-time method for beaten biscuits, which requires, according to one of the FAQ cards, “a smooth, heavy wooden stick.” Search for Chatham Artillery punch, developed in Savannah during colonial times, and the first result is from the New York Times—the so-called original recipe. But in the FAQ boxes, three versions sit side-by-side, filed neatly under C. None match the Times recipe. One yields three gallons and serves fifty. Another yields twelve gallons and recommends a cedar tub. A photocopied recipe from the Savannah Cook Book, folded and taped to a card, calls it a “suave and deceitful brew.”

In 2005, playwright Richard Foreman was already worrying that the internet had wrought a blander way of being, containing “less and less of an inner repertory of dense cultural inheritance—as we all become ‘pancake people’—spread wide and thin as we connect with that vast network of information accessed by the mere touch of a button.” His argument would perhaps have resonated with C. Vann Woodward, who wrote in 1960’s The Burden of Southern History that the “threat of becoming ‘indistinguishable,’ of being submerged under a national steamroller, has haunted the mind of the South for a long time.”

For just as long, fretting about the loss of identity has been fraught. Woodward points out that the Southern identity has always hung on the region’s faults, which was “always simplest, for whatever their reservations about our virtues, our critics were never reluctant to concede us our vices and shortcomings.” But even by 1960, he argues, the faults that defined the South had become the faults of the nation, “standard American faults, shall we say.” Proud Southerners on both ends of the political spectrum still writhe in paroxysms over how to wear the badge.

In the FAQ cards, I found an alluring alternative: knowledge that rooted me deeper in a sense of home, cultural markers I could be proud of—Savannah’s contributions to arts and letters, our particular pronunciations (“If you ever expect to pass yourself off as a Savannah native, you must know the ‘correct’ pronunciation of these names”). Even better, the cache was dressed up in the democratic ideals of the public library, one of the most trusted institutions in America.

These days, librarians largely rely on the internet to find answers, a powerful addition to an arsenal that still includes newspaper archives and reference books. Based on the cards, some visitors to the Bull Street library sought fun facts, knowledge for its own sake (left-handed presidents). Others needed help, solace, community; one card lists resources for adoptees wishing to learn more about their biological parents. Another provides contact information for the NAMES Project Foundation, the organization responsible for the AIDS Memorial Quilt (“meets 3rd Thursday of each month at 6:00 at Hospice Savannah”). Lee says researchers have called, emailed, or visited the reference desk from as far away as Australia. Artists, cookbook authors, novelists, biographers, students from elementary to grad school—all have had reason to stop by for information. It’s pretty to imagine that the library’s reference department served a representative swath of Savannahians, that everyone found what they were looking for.

“All too often the library is viewed as an egalitarian institution providing universal access to information for the general public,” writes Pitzer College professor Todd Honma, in a damning 2005 analysis of libraries’ failure to reckon with race. “However, such idealized visions of a mythic benevolence tend to conveniently gloss over the library’s susceptibility in reproducing and perpetuating racist social structures.” He argues that early libraries’ mission to assimilate was a racial project, one that perpetuated a particular brand of whiteness to “uphold the unequal distribution of wealth, power, and opportunity.”

But libraries designed by and for people of color could do the opposite. A mile from the Bull Street library, around the corner on Henry Street, stands a handsome Prairie-style brick building. Opened in 1914, it operated until 1962 as the library system’s branch for African Americans, but fell into disrepair and was eventually closed. It was restored, expanded, and reopened as a public library branch for all patrons in 2004. The East Henry Street Carnegie Library was one of just two Carnegie libraries built for Black Georgians, and it quickly became a vital hub and rare resource in the South, where Black residents often had limited access to libraries. Supreme Court justice Clarence Thomas and Pulitzer Prize–winning writer James Alan McPherson visited often as young people.

In communities of color, these spaces held transformative possibilities. For activists Paulo Freire and Malcolm X, libraries were wellsprings of radical knowledge—but as Honma points out, mere access to information doesn’t necessarily lead to understanding. Poet and scholar Audre Lorde, who earned a master’s degree in library science and worked as a librarian for many years, wrote that knowledge and understanding “can function in concert, but they do not replace each other.” She eventually left her position to teach, a role she believed she couldn’t fulfill at the library. Honma argues that public libraries are well positioned to take up the cause of social and racial justice, but by providing information without social context, they fail to achieve their potential as agents for change. When justice movements swept the country in the 1960s, Savannah’s Henry Street library seemed poised to serve the struggle for liberation. But the city desegregated its libraries in 1963, and the Henry Street branch deteriorated.

The Bull Street library ostensibly opened to all when the system desegregated. But at public libraries nationwide, the mission to serve everyone equally isn’t always borne out. A 2015 Yale study describes how predominantly white public places, including schools, restaurants, and workplaces, come to be defined as “white spaces,” which Black patrons perceive as off-limits: “What whites see as ‘diverse,’ blacks may perceive as homogeneously white and relatively privileged.” In 1981, librarian Robert Haro studied Latino perceptions of U.S. libraries, and library scholar Richard Rubin summarized the results: “Libraries are often perceived as one of many Anglo institutions that are designed and controlled by Anglos to serve Anglos.”

While library support staffs, which include pages and administrative professionals, tend to reflect the demographics of their communities, graduate degree requirements for librarians have helped stratify the profession. A 2020 Zippia study found that sixty-four percent of librarians in the United States were women, and more than eighty percent were white. Patrons’ experience of the library is shaded by librarians’ individual prejudices. A 2017 study showed, for example, that public service providers, including librarians, were less likely to return emails to senders with Black-sounding names.

In the FAQ cards, Black people—who make up more than half the city’s present-day population—show up in predictable ways, though it’s impossible to know the demographics of the reference desk’s visitors. Martin Luther King Jr. and Maya Angelou appear on multiple cards. Black contributions are filtered through a white lens that confers authority: A newspaper article by a white journalist cites “the Negro race” as the originators of Hoppin’ John. One card relates a story to explain the Black lawn jockeys once common at the end of certain Southern driveways: They may have been inspired by Jocko, the card says, a twelve-year-old who followed his father into service in the Revolutionary War. After Jocko froze to death on the night he crossed the Delaware, George Washington is said to have installed a statue of him at Mount Vernon. When I requested an image of the card for this story, the reference librarian made sure to clarify that this myth is outdated and apocryphal.

Though there are three recipes for the tony Chatham Artillery punch, there are none for traditional Gullah fare. Indigenous groups feature even less, typically as the source of place names. Savannah sits on unceded Creek/Muscogee and Yamasee land, and its name, as a card explains, is believed to have derived from a Muscogee word. One card lists the contact number for the Creek Nation. The Henry Street branch doesn’t have an analogue to the FAQ boxes, but if it did, what would those cards say?

In a way, libraries have aimed to achieve what Google has done (in a fraction of the time): democratize information. And the internet doesn’t look at you sidelong or refuse to email you back. But while libraries still face a host of challenges, from representation among librarians to whether to allow hate groups access to facilities, they’ve increasingly taken on at least a patina of social justice and embraced a broader conception of their mission, including serving the homeless and unemployed. Public libraries now routinely employ social workers to connect patrons with public resources. The Savannah library system serves meals to those facing food insecurity and hosts blood drives. Last year, it launched a Read Woke challenge, which encouraged participants to read ten books that “give voice to the voiceless” and “challenge the status quo.” The library recommended literature in a range of categories, including immigration, Native American voices, and diverse abilities.

But while Honma argues that libraries’ superficial celebrations of diversity and multiculturalism elide any deep critical reflection on race and the institutions’ roles in perpetuating racial inequality, he’s not altogether pessimistic. Libraries have the potential to be empowering places for everyone. In 2020, UNESCO and the International Federation of Library Associations published a manifesto that envisioned libraries as sites of multicultural, multilingual sources of information for all. Aside from “encouraging universal access to cyberspace,” two key missions the document identified were “safeguarding linguistic and cultural heritage” and “supporting the preservation of oral tradition and intangible cultural heritage.”

The FAQ cards let me turn over in my hands some of that intangible cargo. The cards in the boxes are quaint relics from an inflection point in the library’s history, as in-person queries gave way to internet searches, and they safeguard a particularly local body of knowledge. But the cards that aren’t in the boxes speak to another inflection point, as the library, more than a century after its founding, still struggles to live up to its ideal as a truly egalitarian institution. They’re a reminder that in a tourist town of Spanish moss and antebellum homes, the stories we preserve reveal as much as the ones we don’t. As 2020, a year that brought the coronavirus and a wave of social justice movements, drew to a close, the Savannah library system’s then executive director David Singleton promised to “embrace authors and stories that reflect the unique communities we serve.” If the library can transcend platitudes and achieve its mission to serve every facet of society, it can, as Honma writes, redefine literacy and citizenship in the service of social justice.

One old card stands out to Lee. Lots of people, she says, ask about the Ruskin quote engraved across the library’s marble façade. I find the card she’s referring to, yellow and typewritten. The card doesn’t contain the whole quote, but it explains the source and in a cursive annotation adds, “This inscription was suggested by Mrs. B. F. Bullard.” On the way out of the library, I look up and make out the carved words: “This eternal court is open to you, with its society, wide as the world, multitudinous as its days, the chosen, and the mighty, of every place and time.”