The Dollar Done Fell at the Checkerboard Lounge

By Jay Jennings

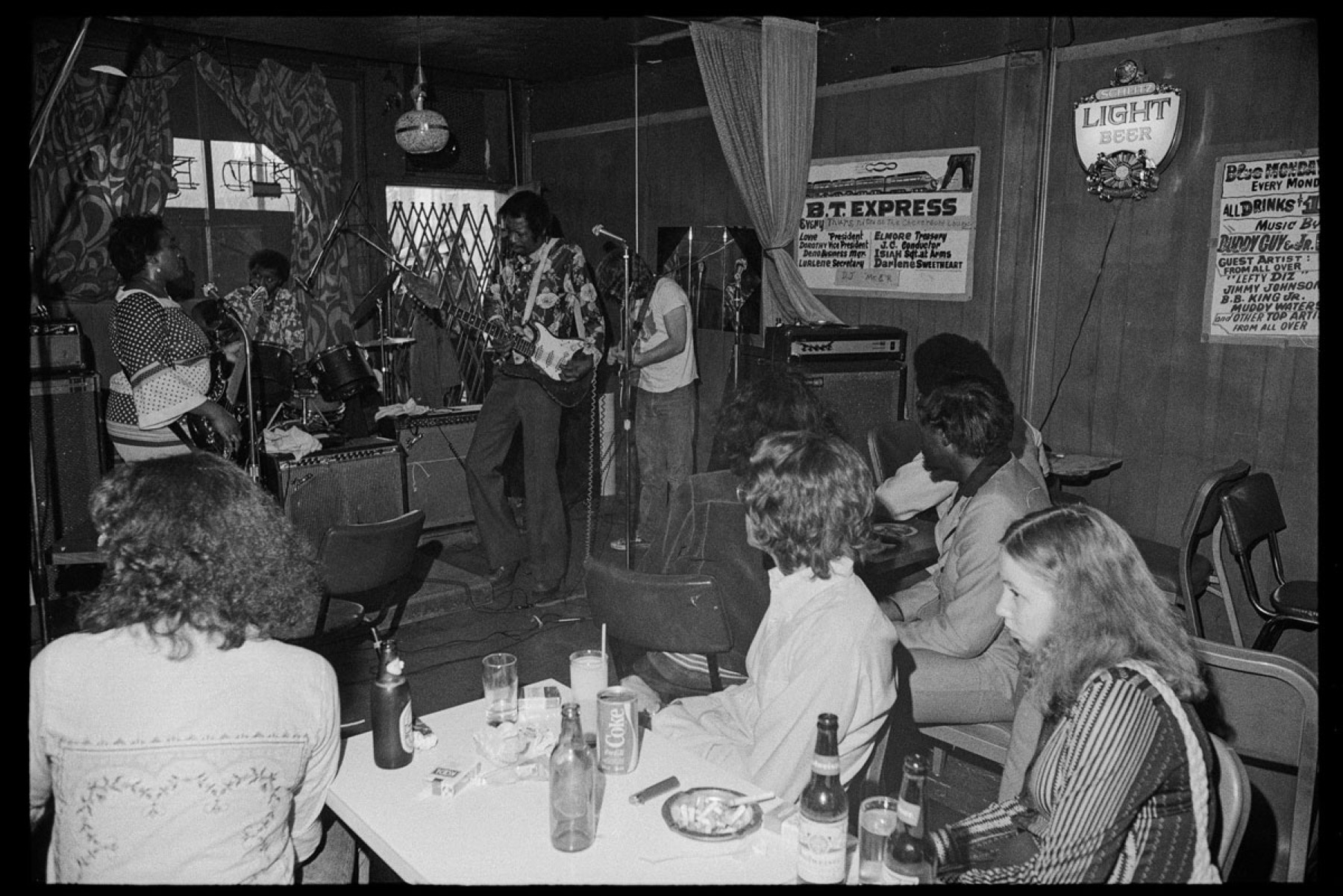

Checkerboard Lounge, 423 E. 43rd St., Chicago, May 30, 1977. Photo by Jonas Dovydenas courtesy the Chicago Ethnic Arts Project collection (AFC 1981/004), American Folklife Center, Library of Congress

When I entered the University of Chicago in the fall of 1980 to pursue my master’s in English, my first class was Introduction to Literary Study, taught by Ned Rosenheim, author of the book What Happens in Literature (1961). As I sat there with my sharpened pencils, I readied my mind for details about philological arcana. For the whole of that session and the next, Professor Rosenheim discussed the wonders of Chicago, with the explicit instruction to get out of Hyde Park: Visit the Art Institute, the Lyric Opera, Wrigley Field, the Steppenwolf Theatre, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Oak Park. Don’t let your graduate years be circumscribed by the campus, as glorious as it is, he insisted. I took this to heart and did all those things, as well as seeing Walter Payton at Soldier Field (in single-digit temperatures), attending a Second City improv show, eating a cheeseburger at the Billy Goat Tavern, and drinking a martini at the Palmer House. One of my most memorable excursions was also one of the closest to the Hyde Park campus (about ten blocks away) but transported me back to the South: the Checkerboard Lounge at 423 E. 43rd Street.

It was well known to U. of C. students and we gathered a group to go. I don’t remember who played that night (my only trip there), but the atmosphere was one of homey welcome. (One piece of advice I was given: Get your beer right away because prices increased by seventy-five percent once the music started, from $1 to $1.75.) I recall that at the entrance was a card table, on which a cash box swallowed our $1 admission, an absurd amount for the quality of the music, a blues master performing almost every night: Buddy Guy, who founded the club in 1972 with L. C. Thurman; Guy’s sometime collaborator Junior Wells, harpist supreme; Muddy Waters; Lefty Dizz; James Cotton. Once we were in the door, a woman with an aluminum pan offered us some spaghetti. The narrow room was divey and intimate, a juke joint on a city thoroughfare. If it was Blue Monday, it’s likely that poet Sterling Plumpp was there, too.

Plumpp, a native of Clinton, Mississippi, was raised by his grandparents, sharecroppers whom he often worked alongside. An outstanding student, he attended college in Kansas and moved to Chicago in 1962, where some relatives lived and where he took a job at the post office while writing poetry. He went on to join the faculty at the University of Illinois at Chicago, spending thirty years there and publishing sixteen books, including Home/Bass (2013), which won an American Book Award. He has spent most of the waking hours of his adult life listening to, thinking about, and writing on the blues, which to his thinking is the crucial American art form. “Nothing that Richard Wright wrote is as authentic as the blues,” he told me recently. “Nothing.” In 2019, he was given the Fuller Award for Lifetime Achievement from the Poetry Foundation and the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame; the cover of the program for that honor shows him sitting outside the Checkerboard, such was his ubiquity there and at other music venues.

“The Checkerboard,” he said, “was a blues club but it was also a living cultural institution…the school where the masters performed….More importantly, it was almost like a training ground for young musicians. What do I mean? Junior Wells, James Cotton, Lefty Dizz would often call these young people up to let them play at the end of the night.” He pauses and laughs. “But then again, most of the time they wouldn’t call you up.”

It is clear that we’re talking mostly about the “old” Checkerboard. Even in its early days, there were a large number of white people like me and my graduate-student cohort in attendance. The Guy and Thurman partnership ended in 1985, and the latter moved the club to Hyde Park in 2005, closer to the university. (It closed for good after Thurman’s death in 2015.) Other clubs where the traditions were passed down—as Muddy Waters had done with Guy at the 708 Club, shortly after Guy moved to Chicago—had already either closed or moved; Plumpp specifically names Theresa’s and Peppers. The contemporary crop of “white-tourist clubs,” as Plumpp calls them, lack the pedagogical legacy of the old South Side venues. “I don’t know whether you can apprentice yourself by sitting in. Although the shows are good.”

My one trip to the Checkerboard in 1981 was sandwiched between two notable recorded performances there. In 1979, Guy tracked a live album, The Dollar Done Fell, released in 1980 and reissued on CD in 1988 under the title Live at the Checkerboard Lounge; later in 1981, the Rolling Stones, in town for a multi-night arena show, visited the club and jammed with Muddy Waters, Guy, and others. After years as a bootleg, the show was released as a CD and DVD in 2012, and selected performances can be found on the Stones’ YouTube channel. Legend has it that it was an impromptu appearance by the band at the club to see Waters, but there’s plenty of evidence, by reporting and by common sense observation of the videos, that it was planned. No matter, both Waters and the Stones—with Mick Jagger rocking a pastel-peach Ellesse tracksuit—revel in the performance, the affection and delight running in both directions. By then they’d had a long relationship with Waters, whom they revered, dating from the mid-1960s, when they toured the South, playing for white audiences early and at the juke joints after. As Keith Richards put it in his autobiography, Life: “You want to be a blues player, the next minute you fucking well are and you’re stuck right amongst them, and there’s Muddy Waters standing next to you.”

Plumpp, who was not at the Checkerboard to see the Stones, nevertheless felt his own affection for the British embrace of and respect for the blues masters as opposed to American musicians’ appropriation and lack of acknowledgment. “They know vocal music in Europe and they study it,” he said. “The Rolling Stones, they are students of the craft of it. The thing that I respect them the most for: they said there’s no way in the world I’m going to sing [on TV’s Shindig!] if you don’t put Howlin’ Wolf in front of me. I never heard Elvis Presley say that.”

I’m not sure Ned Rosenheim ever went to the Checkerboard, but his injunction to get off the Hyde Park campus sent me there (even if I was so absent from campus I once missed a reception for Seamus Heaney). My professor had a counterpart at UIC in Plumpp, who frequently encouraged his students, like future writers Jeffery Renard Allen and Tyehimba Jess, to accompany him to clubs like the Checkerboard. Allen wrote of his teacher, “Clubs are Sterling’s woodshed, immersion in the music the necessary preparation for making.” Plumpp himself has an even more expansive view of the value of his nights out at the clubs. Going to blues and jazz venues, he says, “is the only way you can get a deep understanding of what African American culture is.”

My master’s thesis was on Dr. Johnson’s “Life of Milton,” and in general I played out that year along a well-trod path of traditional academic achievement and indulged my Anglophilic desire to escape my Arkansas upbringing. But at the Checkerboard, and in my subsequent reading of fellow Arkansan Robert Palmer’s Deep Blues published the same year, I felt a nascent interest in and appreciation for artistic expression that was more vital and closer to home—I should have been studying Robert Johnson and Little Milton instead.