Fye-Veaux

By Joi Gilliam

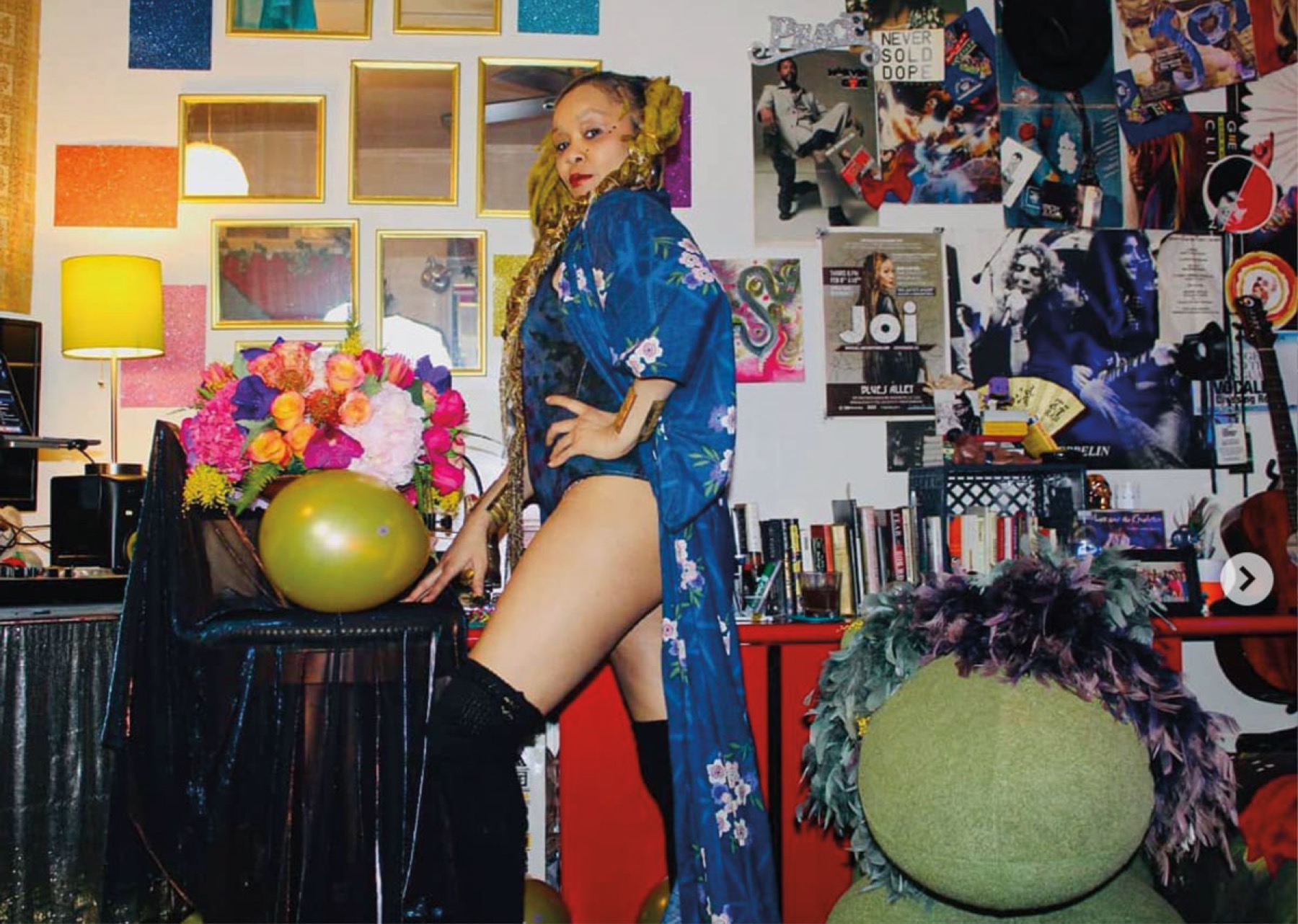

Top: Photo by Joi Gilliam. Courtesy the author. Bottom: Photos by Daniel Hastings. Courtesy the author

In the summer of 1993, I wrote and recorded my first album, The Pendulum Vibe, in less than two weeks with Dallas Austin at his Atlanta studio, DARP. I was twenty-two. We’d met the previous year at a Music Row studio in Nashville, my hometown, where he was recording an album for the experimental funk band Highland Place Mobsters and enjoying newfound success as one of the world’s hottest young music producers with hits for ABC, TLC, and Boyz II Men already under his belt.

Our creative kinship was instant. I was the Black Southern belle rebel who refused to conform to the constraints of expected creative homogeny. Dallas was the young gun with the Midas touch who knew his way around the music industry and welcomed the opportunity to explore uncharted territory with me. We were very proud of the album we created and had many impromptu listening sessions with comrades and associates from all over the country. Their reaction was always, “Play it again.”

The album begins with “Stand,” the first verse of a song called “I’m Gon’ Stand!!!” by Sweet Honey in the Rock.

We will not bow down to racism

We will not bow down to injustice

We will not bow down to exploitation

I’m gon’ stand

I’m gon’ stand

“Stand” introduced my own song called “Freedom.” And “Freedom” was chosen for the soundtrack of the 1995 Mario Van Peebles film Panther, after the soundtrack’s supervisor heard the song via DARP’S “hold music.” It became a unifying battle cry performed by a large ensemble of music’s best and brightest Black female artists at the time. All these amazing women—many I grew up listening to and admiring, some just starting out like me—all there to sing MY song. Queen Latifah, Mary J. Blige, Yo-yo, TLC, Aaliyah, Patra, En Vogue, Vanessa Williams, Caron Wheeler, Brownstone, Pebbles, and Amel Larrieux. I was there and it still seems unreal. Thanks to the video and a few photos floating around the ’net I am often reminded of my early style: the top hat, long blond braids, my favorite black sequined leggings my mom gave me, a vintage button-down tied in the front, my favorite silver stilettos that I wore damn near every day.

Angie Stone, the vocal arranger, directed us as a choir. We were all different musicians, but the world got to feel us as one wonderful, unified voice. After filming and recording for the better part of the day, the soundtrack executives decided to add “Stand” to the track, as well, to accommodate the overflow of participation.

I’d seen Sweet Honey in the Rock sing at Fisk Memorial Hall, the home performance venue of the Jubilee Singers, when I was in junior high. Dr. Bernice Johnson Reagon, Evelyn Maria Harris, and Ysaye Maria Barnwell taught me what it means to lead a song. As they stood on that stage, I was enraptured by all that they were: regal, beautiful, brilliant, unapologetically Black women, masters of their craft doing the righteous work of healing through the gift of song. I devoured every morsel I could find of their discography: “In the Upper Room,” “No Images,” “Freedom Song,” “Meyango,” “Testimony,” “Gift of Love,” and “Battle for My Life.” Seeing them live and studying them daily sparked and crystalized my passion for variety in song composition. The differences in their voices combined so perfectly to make an even more distinct collective sound, and deepened my appreciation for vocal originality.

My entire childhood I feasted on a consistent diet of music that demanded a soul-opening abandon, like Minnie, Prince, Chaka, S.O.S. Band, Marvin, Labelle, Sade, Luther, Whitney, Rick and the Mary Jane Girls, and my childhood pastor, Oscar C. Myles, who would whip the congregation into such a shouting praise frenzy he couldn’t even preach the sermon. I watched Parliament-Funkadelic land the Mothership when I was six and saw Michael Jackson, Stephanie Mills, and Teddy Pendergrass at Nashville’s Municipal Auditorium when I was eight.

In tenth grade, I won the school talent show when I sang a rendition of “Everything Must Change” inspired by the great Jean Carne. Fellow Nashvillian Gary “Lil G” Jenkins, best known as the lead singer of r&b group Silk, accompanied me on piano. As I closed my eyes and took a deep breath to sing “and hummingbirds do fly,” I was hyper aware of how my voice sounded in my own ears. How I felt as if I were roaring. I held the note for several seconds and the swell of the audience’s cheers intensified. I took a dramatic, abrupt pause and my entire body quickly shook and jerked with a ripple wave from head to toe. I could not control that phenomenon. It demanded to have its way and I could only oblige. I knew I had been righteously invaded for my own good: a lightning bolt of vulnerability and submission. The way the crowd went wild let me know they felt it, too.

Word soon got around that The Pendulum Vibe was “on some next shit” and the first single, “Sunshine & The Rain,” was the fuse of that creative bomb. The video offered a starkly different visual from what was expected of a Black artist on the early ’90s r&b landscape. I never considered myself an r&b artist, anyway. In the clip, I wore platform shell-toe sneakers, blond low-cut hair, and a sheer black nylon maxi-length dress, sporting only a thong underneath. In other scenes I am covered in silver glitter, hanging from a meat hook, dancing under the desert moonlight. I considered myself, with no barriers of categorical constraint, a dope creative who was here to create original dope shit. The video and album caught the attention of Lenny Kravitz and Madonna, who tapped Dallas to produce Bedtime Stories after hearing my songs.

My label didn’t even really know what to call what I was doing. Who is this peculiar Black girl from Tennessee? How do we even begin to market this? Can she be a little bit more like Mary J. Blige? (An actual question in a meeting.) In spite of no significant push from my label, regular features in magazines like Vibe and Honey and New York City scribes like Mimi Valdes, Joan Morgan, PhD, and Emil Wilbekin helped to keep me relevant as an underground artist.

The proverbial mainstream was watching and taking notes, though. Quite a few ingenues emerged looking very similar to me; some were even similarly named. Other than U.K. artists, the only Black women making what would later be known as alt soul or progressive r&b were Meshell Ndegeocello and me. “Biting” was a no-no back then, yet it was clear to me that my swag was being studied and incrementally copied by more folks, male and female, than I can, or care to, name. EVERYBODY was at my shows, leaving with a vivid tale of what they saw, absorbing my visuals and styles. At legendary ATL venue The Point, I saw the style of my late great sister friend Peach, the legendary front woman of the funk rock band Whild Peach, being regurgitated by another band as if it were their own. In the thick of experiencing the same kind of style siphoning, I was inspired to write “Meow/Copycat” with Fishbone, which is the last track on my second album, Amoeba Cleansing Syndrome. The version on the album is from when I opened for D’Angelo in Atlanta in ’95 at the Variety Playhouse concert wearing silver nipplets, black latex hot pants, a white boa, and silver thigh-high boots, nods to Betty Mabry Davis and my daddy.

I suspect it has to do with being a five-decade inhabitant of this wild-ass space-spinning water ball we call home and my two-terabyte brain being just about full, but when I think of all that has happened, I’d be lying if I claimed to be able to recall most of it. Perhaps it’s the internalized heartbreak of every wrong I’ve experienced. Being simultaneously heralded and disregarded within the music industry is a mindfuck that has tested my sanity, grace, grit, and self-understanding. If not for my soul’s core knowing, I would have succumbed to it long ago. I identify as a fully protected being—even the worst pains, losses, disappointments, and fuck-ups have benefited me to some degree. Aging is a bodacious gangster bitch, and the body and mind have a way of jettisoning what they don’t need.

January 25, 2021, my fiftieth birthday, was a wondrous, miraculous, and strange milestone. I did not know if I’d make it to fifty or not. My dad, Joe Gilliam Jr., passed away Christmas morning in 2000, four days shy of his fiftieth. He was the first Black quarterback in the NFL to start in a regular season game. He had been exceptionally bright as a student and an All-American in high school and college before going on to play for the Steelers. A diver and swimmer, he threw me into the pool at four to my mother’s horror, but I swam like he was certain I would. Gregarious, magnetic, deeply beloved, handsome, wild, and funny. A wearer of silver platform knee boots, man bags, and hip-hugging lace-up bell bottoms. Shirt, optional. He proudly taught me to throw a perfect spiral as a kid and he proudly walked me down the aisle on my wedding day.

I was twenty-nine when he died, so the abstraction of fifty seemed like a far, far-away land to which I’d never arrive. Yet, here I am—older, wiser, with joints that snap, crackle, and pop in the morning. In many ways, I am better. I released my fifth album, SIR Rebekkah Holylove, twelve years after my fourth, with pen and performance still in tip-top shape. Still giving vanguard-original realness since ’93 while offering current grown-ass truths that give a window to the complexity of a liberated woman.

At fifty, my impact is woven into the fabric of the Atlanta music scene and every audacious Black artist in this country who has come after me whether they know it or not. As the end of the analog wave approached and the digital age dawned, fashion audacity and sexual freedom owned by a smart, carefree Black girl were not the norm. I was an anomaly then. To see confidence, self-awareness, body positivity, and intelligence become transformative forces for so many young Black people lets me know the future is ours just as I always knew it would be. I have done my part to make it so.

I feel like a super smokin’ hot youthful OG Godmama who observes her children proudly from a distance. Who knew when 3 Stacks said, “the South got somethin’ to say,” that those words were prophecy giving future generations unshakable ground to stand on? The South influences everything these days while still fighting for its respect. The more things change the more they stay the same. That’s the thing about audacity. It’s contagious and every new generation ups the ante.