Country Boy Gone City

A ballad of Johnny Bristol, Al Green, and Battle Creek’s Bloody Corner

By Rebecca Bengal

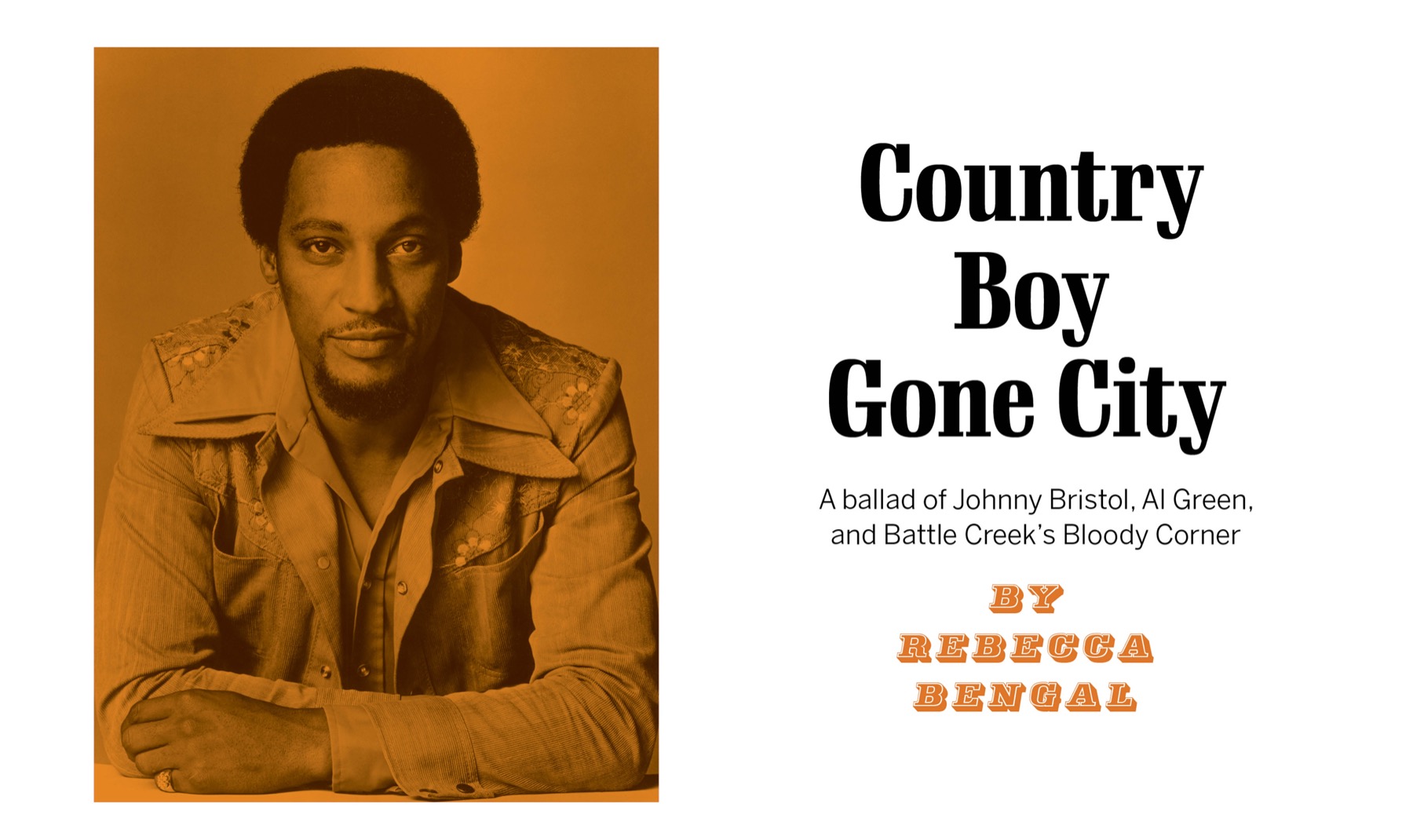

It is 1976 and Dick Clark is interviewing Johnny Bristol, the r&b and soul singer and Motown songwriter and producer, on American Bandstand. Bristol is wearing a slate blue suit tailored to his six-foot-three or four frame and what must rank in the top ten pairs of coolest sunglasses of all time, lightly shaded so that you imagine the world appeared shadowed in a permanent vapor. That is, he is dressed worlds apart from the place where we were each born, nearly forty years apart—Morganton, North Carolina, in the Appalachian foothills, a town that is frequently described in relation to other, larger places nearby: a stop off I-40, surrounded by the cerulean haze of the Blue Ridge Mountains; a town of state-run schools and institutions and, in Bristol’s day before many of the mills were closed, a factory town where trees got turned into furniture and cotton into lingerie and hosiery, and where music venues and bars still existed only on the sly. Or, as Bristol sings in a funked-out soulful, Bill Withers–esque ballad of Morganton, “It’s just a clean-faced small place in the land of Carolina.”

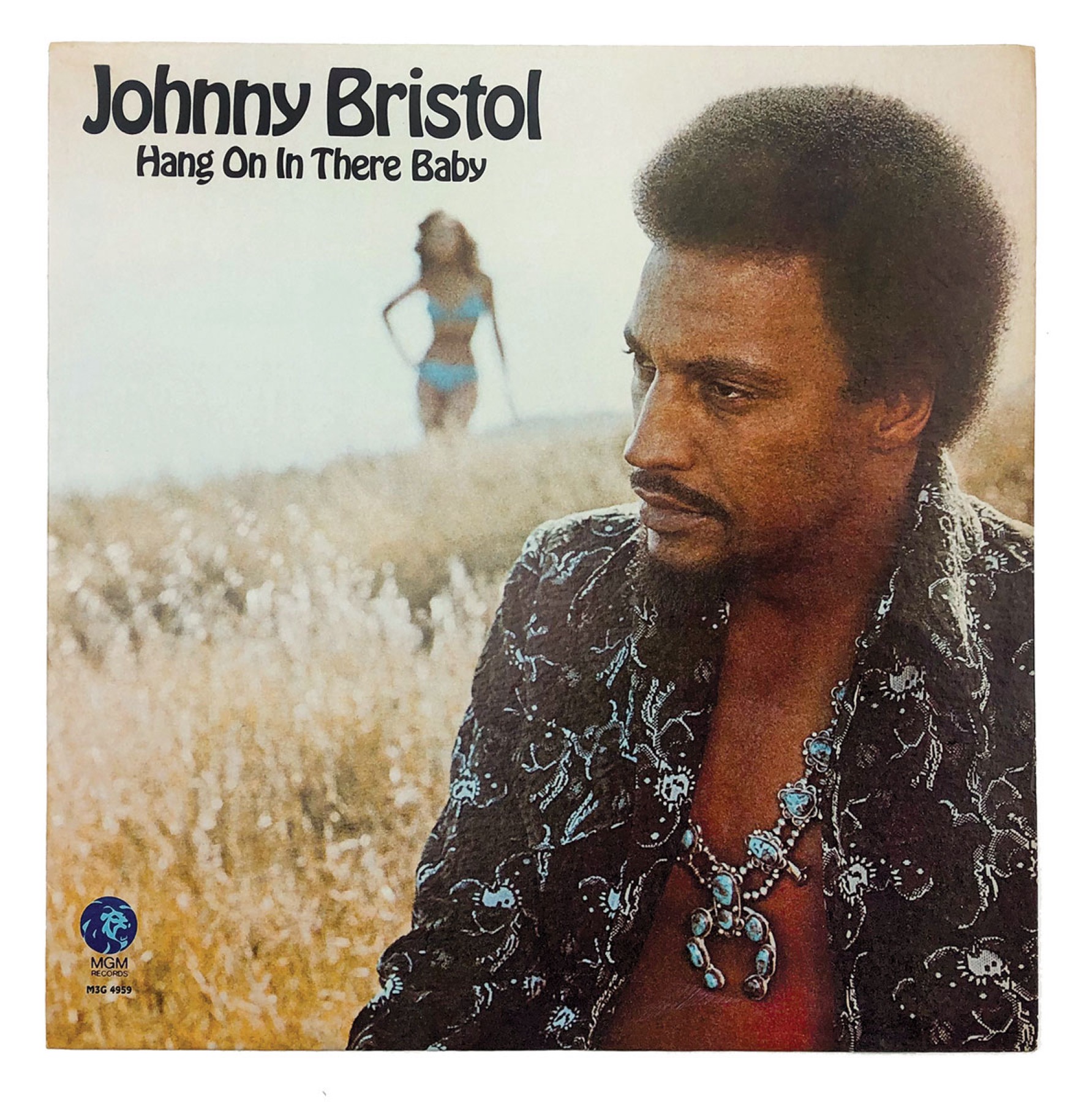

On Bandstand, Bristol is fresh off of a Grammy nomination for Best New Artist for “Hang On In There, Baby,” his biggest solo record, number eight on the Hot 100s. He takes a breath before attempting to enumerate some of the greats he’s worked with as a producer (often alongside co-producer Harvey Fuqua) and/or songs he’s written. Among them: Stevie Wonder (“Yester-Me, Yester-You, Yesterday”), David Ruffin (“My Whole World Ended [The Moment You Left Me]”), Smokey Robinson and the Miracles (“We’ve Come Too Far To End It Now”), Gladys Knight and the Pips (“Daddy Could Swear, I Declare” and “I Don’t Want To Do Wrong”), Jerry Butler (“Memories Don’t Leave Like People Do”), Jr. Walker & the All-Stars (“How Sweet It Is [To Be Loved By You]”). Bristol supplied the lone male backing vocal in the Supremes’ “Someday We’ll Be Together,” a song he originally recorded with his erstwhile collaborator Jackey Beavers almost a decade before Diana Ross sang it. And on and on, starting with his Motown days and heading on into CBS Records (Boz Scaggs, Tom Jones, Johnny Mathis). And that just gets us to the mid-Seventies.

The most fun, Bristol says, at Clark’s prodding, was working with Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell. Of Terrell, he says, “When she walked into a studio she was always up, never down, she was ready.” With Bristol and Fuqua co-producing, Gaye and Terrell recorded the original version of “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough,” in 1967 on Tamla Records, which became Motown. Bristol recorded them separately, but still made their chemistry audible, palpable. The “tick-a-tick” sound of two drumsticks striking the rim at the start of the song is Johnny Bristol helping out the drummer.

But by 1974, he’s onstage in his own right. When Bristol writes “Hang On In There, Baby,” he keeps it for himself—in fact, it becomes the title song of his debut album. “[T]hat song would be a hit on anyone,” he tells Billboard editor Adam White years later. Look it up now, and searches for the song yield Google-automated queries like “Did Barry White sing ‘Hang On In There, Baby’?” The slip is forgivable, flattering—who wouldn’t want to claim that deep bass bedroom vocal and its inevitable comparisons to White’s “Love Theme”? But the song is all Bristol; Barry White never covered it. (Bette Midler would, however, in 1979.)

On Bandstand, though, Dick Clark gets momentarily serious.

Clark: We talked about the good times but tell me what was your lowest time?

Bristol: I think when I started singing in a duet and we worked in the Bloody Corner—

Clark: Wait, the WHAT?

Bristol (unflappable in those shades, but perhaps cracking the slightest smile): The Bloody Corner.

Clark: That was the name of the joint you worked in?

Bristol: That was the name of the joint, right. We had to throw guys through the window, right. (He pantomimes scooping a body, sailing it out an invisible door.)

What Bristol doesn’t have time to mention in this three-minute interview is that the Bloody Corner (real name, the El Grotto Lounge, in Battle Creek, Michigan) also happens to be the spot where Junior Walker builds a following—in fact, it is where Junior Walker & the All Stars first perform their hit “Shotgun,” allegedly inspired by the shooting dance motions of the crowd. The crowd eats up the song, they love it so much they’ll often make him play it more than once in a row. Bristol, who will wind up producing Walker at Motown, doesn’t get to tell Dick Clark that the El Grotto was the club where Al Green first gigged, so young he had to wait outside in the car until it was absolutely time to go onstage. Or how all of them, including Jackey Beavers, the other half of Bristol’s first recording duo, Johnny & Jackey, had grown up in little towns down South—in Arkansas, Georgia, and North Carolina—and carried something of those sounds up north with them in the era of the Great Migration, unconsciously tracing ancestral paths to freedom. It just so happened that they intersected in a rough little corner bar which was itself begun in resistance to bigotry, tucked inside a town that was once a major way station on the Underground Railroad, inside a state where utopian-minded travelers had sought various refuges for more than a century. And yet, growing up in the Eighties, as I popped my Stevie Wonder mixtapes and my Michael and Janet Jackson cassettes into a Kmart boombox, growing up with my mom’s Motown records, I was never told that someone from our town had a hand in all this music.

Mapping Battle Creek

In recent years for reasons unknown a couple local Morganton businesses (a gym, for one) started appropriating the nickname “Motown.” Never mind that actual Motown, the house that Berry Gordy built in Detroit, Michigan, is a good ten, eleven-hour drive north.

People from Michigan map the lower peninsula of their state on the hand. Picture the right, palm facing up. Lake Huron flows from the middle finger and cascades over the pointer, Lake Michigan lies flush to the pinkie, Detroit at the bottom of the thumb. From Detroit, hang a left across and here is the small city of Battle Creek, wedged in the lower palm, parallel to the ring finger, within the synovial lining that connects the joints. On the hand depicted on an acupuncture chart, Battle Creek would be located right around the pressure point that corresponds to the small intestine. That is, it is above the crease of the wrist, the point that connects to the heart, which lies to the east, and south.

To anyone raised anywhere in America on breakfast cereal, the name Battle Creek probably triggers faint recognition from earliest days sleepily inhaling the fine print scrolling down the boxes of puffed grains and crisped rice. It has been the headquarters of the Kellogg company since 1906, founded by W.K. Kellogg shortly after his brother Thomas first developed cornflakes to serve to patients at the Battle Creek Sanitorium, a hospital and health spa.

In the mid-1800s, Quakers and abolitionists flock to Battle Creek, where slavery is not enforced. Arriving from New York state, Erastus Hussey and his wife, Sarah, open a general store, publish a newspaper, and will eventually help more than a thousand enslaved fugitives escape to freedom. In 1857, six years after delivering her “Ain’t I a Woman?” speech in Akron, Ohio, at the age of sixty, Sojourner Truth joins friends and her daughter Elizabeth in Harmonia, a utopian village near Battle Creek founded by Spiritualists—a religious movement based on a belief in the possibility of communication between the living and the dead. In 1862, after a tornado destroys much of the village, Harmonia becomes an actual ghost town and in 1867, Truth moves into Battle Creek proper. In 1884, Frederick Douglass addresses the town’s Emancipation Day celebration, speaking to an audience he fears had already forgotten the horrors of the Civil War twenty years earlier. “Events which shook the earth, air and sky, and plowed themselves beam deep into the very soul of the nation have already fallen away into the dim deceptive haze of the past,” Douglass says, and rallies the Northern crowd to rise to meet a present threat: “You and I and all of us are bound never to rest until the ballot box is respected in every state.”

More than a century later, when the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center in Cincinnati is preparing its opening, the museum’s director, John Fleming, envisions the museum as a connector of paths and stories, like the hub of a wheel, illuminating all the routes that had been traveled in secret. “What we did was to develop maps of the Underground Railroad, to show where these trails emerge out of the South, going up from Maryland and Virginia, into Pennsylvania and New York,” Fleming, now the director emeritus, tells me from Ohio. “There were trails that led from Arkansas, trails from Kentucky through Cleveland, and then, when they would have gone into Battle Creek, those trails would have come up through Cincinnati, almost following [present-day] Interstate 70, up into Michigan.” Dr. Fleming, who also directs the newly opened National Museum of African American Music in Nashville, is from my hometown too. He is seven years younger than Johnny Bristol but remembers watching Bristol’s teenage group, the Singing Yellow Jackets, sometimes called simply the Jackets, play dances at Olive Hill High School, an all-Black public school in officially segregated times.

Lonely and Blue

Their first duet is a coincidence. It is 1956 and Jackey Beavers, standing in the barracks shower of the Selfridge Air Force Base outside Detroit, overhears Johnny Bristol and another Air Force private singing as they walked by; he chimes in. “You sang?” Bristol asks him later. “Yeah,” he answers, “I sang.”

With three others, Beavers and Bristol form a quintet—the Five Jokers, or the High Fives, depending on who is telling the story. The group gigs at the Gold Room on the top floor of the 20 Grand, an upscale Detroit nightclub that catered exclusively to a Black clientele. It’s high times for a couple of young servicemen who hailed from little towns down South—Jackey Beavers from Cartersville, Georgia, and Johnny Bristol from Morganton, North Carolina.

Eventually the five-piece whittles itself down to two. As Bristol recounts years later, “We came from the deep south, didn’t drink much and do all that stuff, so we broke off from the group and started Johnny & Jackey.”

A brother of Duke Fakir of the Four Tops connects Bristol and Beavers to Gwendolyn Gordy, who begins managing them. They debut with “Lonely and Blue,” a woozy, swoony doo-wop number, released in 1959 as an A-side 45 for Anna Records, a forerunner of Motown, named for Gwendolyn’s sister. The year 1959 is when the Motown dynasty begins: Gwen’s brother Berry Gordy buys the now iconic two-story Detroit house with the bright blue front doors that he’ll outfit with recording studios and offices and will eventually christen Hitsville USA. Motown means nothing to the military, though, and very much against their protests, Bristol and Beavers are given orders to be transferred to Fort Custer, a hundred and twenty miles from Detroit. They navigate a blizzard in Bristol’s 1951 Ford and on their first Saturday night out on the town of Battle Creek, they trail along with other fellow soldiers, winding up at the oval-shaped bar of the El Grotto Lounge.

Back to the map. Between the era of the Railroad and the Great Migration, Black people made inroads to Michigan for down-time leisure. A hundred and fifty miles northeast of Battle Creek, between the pinkie and ring fingers, was Idlewild, known as the Black Eden, a year-round resort. Idlewild was a vacation refuge for Black Americans in Jim Crow times in the spirit of American Beach outside Jacksonville, Florida, immortalized by Zora Neale Hurston in the Federal Writers’ Project WPA guide she wrote about her home state in the 1930s. Idlewild was also in the spirit of Freeman’s Beach aka Bop City near Wilmington, North Carolina, where a young Assata Shakur worked collecting parking money in the 1950s (Bop City was owned by Shakur’s grandparents). Part of Idlewild’s draw, too, was its array of supper clubs for a Black clientele, places like the Purple Palace, the Paradise/Fiesta Club, the Club Flamingo, the Fashion Flair. In the 1950s, when Idlewild became a stop on the so-called chitlin circuit of far-flung small venues, Aretha Franklin, Sammy Davis Jr., B. B. King, Jerry Butler, Jackie Wilson, and Brook Benton all performed there, as the Eastern North Carolina–born writer Randall Kenan documents in his 1999 narrative Walking on Water: Black American Lives at the Turn of the Twenty-First Century. Still more rare in its run (1912 to the early 1960s), individual lots and houses in Idlewild had been sold primarily to Black vacationers, among them Dr. Daniel Hale Williams, the first doctor to successfully perform open-heart surgery; Madam C.J. Walker, the first Black woman millionaire; and North Carolina author Charles Waddell Chestnutt, the first Black writer to publish short fiction in The Atlantic.

Many lots were bought sight unseen. In 1921, W.E.B. DuBois, who purchased several himself, wrote in the NAACP magazine The Crisis that it was “the beautifulest stretch I have seen for twenty years; and then to that add fellowship.” Much like its counterparts, when the passage of the Civil Rights Act made it safer to explore other destinations, people came to Idlewild less frequently. When Kenan visited in the 1990s, the Flamingo Bar was the only one of the original supper clubs still standing. He met a woman who reminisced about “how wonderful it had been to be in a town where after you got off Route 10, all you saw was black faces. It was like coming to another world, a black country.”

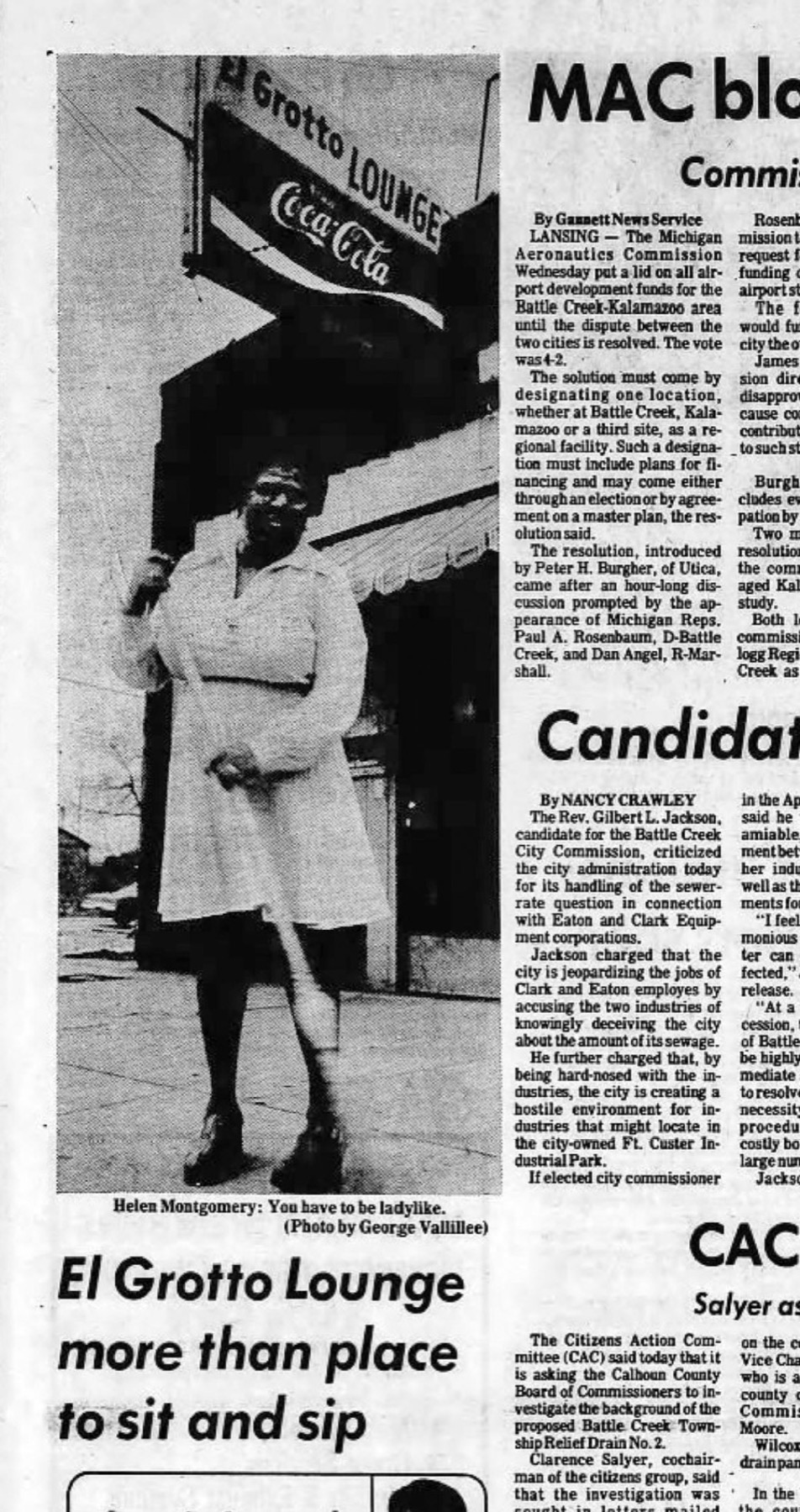

News clipping, 1975.

The Creations and Junior Walker at the El Grotto Lounge, left to right: Gene Mason, Curtis Rogers, Lee Virgis, Junior Walker, Al Green, Willie Woods. Photo courtesy Michigan Rock and Roll Legends

The El Grotto, aka The Bloody Corner

Nonetheless, one night in the 1940s, just down the road from Idlewild in historically abolitionist Battle Creek, Robert Montgomery—nicknamed Snap, a Navy vet and a Kellogg’s worker, a husband and father—leaves a local bar to the sound of breaking glass as the bartender buses the spot where Montgomery had been seated. Better to destroy a glass touched by a Black man than to wash it and pour a drink in it for a white patron. That does it for Snap. Not long after this incident, he and his wife, Helen, both quit their jobs. In 1949, they open their own spot, the Corner, at the intersection of Kendall and South Hamblin Streets, a place that has already been through a few past lives. When an adjacent pool hall shuts down, they acquire that too and, inspired by a bar they visit on a trip to California, change the name to the El Grotto Lounge. (The origin story of Johnny & Jackey and of the bar is told at length in Here I Stand: One City’s Musical History, a 2003 book by Sonya and Sean Hollins, and in the Battle Creek Enquirer archives.) The El Grotto is a neighborhood bar—beer, wine, records on the jukebox, fights on the regular, and sometimes, guns drawn. Miss Helen, as patrons call her, hopefully arranges flowers in a giant planter near the entrance. It’s no Gold Room at the 20 Grand, it’s no Paradise Room or Purple Palace at Idlewild, but for Bristol and Beavers, a couple of soldiers who can’t take the time off to tour around the country, it’s something.

When Johnny & Jackey convince Miss Helen to let them perform, they become the first live act at the El Grotto, and their performances begin filling up the 300-capacity club, paving the way for a number of iconic acts in their nascent years: for Kansas-born Wade Flemons, then the star of a doo-wop group called the Shifters, before he goes on to become one-third of Earth, Wind & Fire; for the girl group the Velvelettes, who will eventually record with Bristol at Motown; for Alabama-raised comedian Jimmy Lynch, who records his live album Funky Tramp at the El Grotto; for the Royaliers; for burlesque shows, live snakes, and, at least once, for an audience that includes Muhammad Ali. Johnny & Jackey’s pay for a gig at the El Grotto ($25) may be equal to a week of kitchen patrol on the base, but it isn’t much for two men who are each newly married and starting families (in 1984, Bristol’s first wife, Maude Bristol Perry, would become the first woman mayor of Battle Creek, where she still lives and where a street was named for her in May 2021). When Johnny & Jackey do manage to play out of town they have to stick within driving range of the base. Bristol recalls to Adam White how they’d pack up in Jackey’s car and stop in towns in Indiana, Michigan, and Ohio “just singing in different places in our little red bowties. If you saw a picture, you’d die.”

Listening to Johnny & Jackey’s original version of “Someday We’ll Be Together,” a rare 45 on Harvey Fuqua’s Tri-Phi label is extra bittersweet. It’s released in 1961, a few years before they part ways around 1963. Beavers has a baby on the way; he’s in danger of being fired if he misses another shift at his new hospital job. When Johnny & Jackey are invited to play in Beavers’s home state, at the Royal Peach in Atlanta, Beavers regretfully declines. “I was miserable, and Johnny was too,” he remembers in Here I Stand. Bristol’s first marriage is over or close to; he heads to Detroit, where the Motown family is growing to include both Tri-Phi and Anna Records and others, where marriages bloom out of work (Fuqua is wed to Gwen Gordy, and Bristol will marry her sister Iris) and where he strikes up a beautiful and longtime producing partnership with Fuqua. In 1969, at Berry Gordy’s urging, “Someday We’ll Be Together” is given to Diana Ross for her final Supremes album—the intimation being that maybe, one day, Ross will reunite with bandmates Mary Wilson and Cindy Birdsong, who don’t appear on the recording, which Bristol renders as gorgeously lush and symphonic. Embedded deep within are his own ad-libs, and the steady, captivating riff that is the heart of the Johnny & Jackey original. Theirs hearkens back to a sound hailing from farther South than each of them—a sweetly intimate stripped-down tune whose rhythm feels in kinship with early Jamaican ska, whose melody contains a yearning for the someday that never will come.

Hang On In There, Baby

“Black music is fugitive music,” Harmony Holiday has written in this magazine. “It often occupies the sound and space of escape, of running away, denying, rejecting, moving on, walking by.”

Al Green, born Albert Leornes Greene in St. Francis County, Arkansas, not far from the township of Greasy Corner, is raised first in the nearby and since-gone town of Jacknash, where his father Robert works as a sharecropper, drinks on Saturday nights, and on Sundays sings gospel. It is 1955 when Robert opens an envelope and discovers that the total earnings for an entire year of hard labor amount to just $800. How many other migration stories begin like this one? He and his wife wake the kids in the middle of the night and pack everything that will fit into their GMC truck, strapping a mattress on top, none of the kids able to envision quite where they are going as they fit themselves where they can, among and underneath the family’s hastily grabbed possessions. Robert Greene follows more recent paths too—Al’s older brother had already left Arkansas for Grand Rapids, Michigan, and sent word that there were jobs to be found.

The Greenes might have driven past Blytheville, the birthplace of Autry DeWalt Mixon Jr. née Junior Walker, whose own family will move up to South Bend, Indiana, and whose lightning performances Al will come to know in about a decade when they share five-sets-a-night gigs at the El Grotto. The family’s middle-of-the-night journey is an unconscious repeat of the nocturnal paths traveled by ancestors in the days of the Underground Railroad. They reclaim the routes Candacy Taylor charts in The Overground Railroad, her history of the Green Book travel guides. They travel the roads taken by six million others who flee the South in the six decades of the Great Migration that Isabel Wilkerson chronicles in The Warmth of Other Suns. Some of the maps of those routes resemble weather maps, wind currents, or the reverse of migratory birds, traveling against the season toward the promise of a brighter one.

In Idlewild, Michigan, Calvin Cormier, one-half of a local couple Randall Kenan meets, describes seeing salmon swim for the first time. “And you ought to see them when they run up. The river is going down, they’re coming up, they’re swimming up and you’ll see them, swimming just to get up....I mean, they’re strong fish, and they have to fight the currents and everything. Just to get up here.” Before Michigan, the Cormiers lived in Pasadena, but Calvin was raised in Texas City, Texas. “I’d never heard of Idlewild.”

Whatever Al Green’s father is driving toward must feel like myth too, bound in faith. Think of the way the artist Dawoud Bey’s Night Coming Tenderly, Black photographs imagine nocturnal landscapes along the Underground Railroad as they would have been seen by those fleeing enslavement, traveling under the protection of blackness. The series of pictures references a dream—“While night comes on gently, / Dark like me— / That is my dream!”—a Langston Hughes verse.

Think of the way stories spread, how they are passed along and embellished to convince those who must travel on imagination and belief—chasing the California gold rush, crops in the Depression, the shelter of a city for anyone fleeing repression. I’m from Johnny Bristol’s hometown, but my grandparents on both sides of the family grew up farming for a living. One grandfather, determined to escape cotton picking, hopped trains to Texas, a place he could hardly envision, following the rumor of easier crops—and had to hitchhike back home when he discovered he’d mistimed their harvest. When I’d try to explain New York City to my paternal grandmother, a farmer and a chicken factory worker, I’d see her eyes cloud a little. I wish I’d asked her then what she pictured, if in her mind when I left, I just dissolved altogether. On the phone she’d want to know the things she could hold on to: what the weather was like, what I was cooking, when I was coming home.

“What’s much harder to find in a book is the experience of leaving everything behind,” Green remembers in Take Me to the River, his 2000 autobiography. He was about nine years old when the family migrated north and didn’t much care for the reality of Grand Rapids (an hour and change north of Battle Creek). “As far as I was concerned, Michigan might just as well have been the dark side of the moon...it sure was cold enough to be. I couldn’t have imagined a place more distant and different from the warm nights and wide-open fields of my home.”

Eventually Al joins the school choir, and tunes in to WCHB, the Detroit station that played Nat King Cole, Little Richard, Chuck Berry, and a song by a distant cousin of his from West Memphis, Arkansas—Herman, better known as Junior Parker, who had a hit with “Mystery Train”: “It sent shivers down my spine,” Green writes, “from the very first notes.”

Robert Greene reestablishes the family gospel choir, and they tour as far away as Canada and New York City, singing “Mary Don’t You Weep” and “How I Got Over.” Meanwhile Al hums along to Stevie Wonder and Little Eva in secret, but when his father catches him listening to Jackie Wilson’s “A Woman, A Lover, A Friend,” he breaks the record and the player. Al runs away from home, determined to go out and buy the record again. (Once, asked about her father’s influences, Johnny Bristol’s youngest daughter Karla Gordy Bristol says, “I think everyone back then was influenced by Jackie Wilson.”) With two friends, Green forms a band, Al Green & the Creations, and by late fall of 1966, they’re putting up handbills for a show at the El Grotto Lounge in nearby Battle Creek—“a smoky dive on the outskirts of town.” It won’t be long before Al Green & the Creations have a hit on their hands with “Back Up Train,” and bookings at the Apollo, and it won’t be long before Al meets his future Hi Records producer Willie Mitchell on a shared bill in Midland, Texas, a meeting that paves the way for his return South to Memphis.

The El Grotto is a neighborhood bar—beer, wine, records on the jukebox, fights on the regular, and sometimes, guns drawn.

Mind’s Going Back to the Place Where I Was Born

Bristol is thirty-six years old, a father of three, when he returns to North Carolina for Johnny Bristol Day. He’s just released a second album, Feeling the Magic (1975), which includes an ode to his hometown, written in a hotel in New York City: “I’m just sittin’ here all alone, but my mind’s goin’ back to Morganton...North Carolina.” When he sings “North Carolina” in that refrain, he emphasizes the genuine accent of the place; there’s a palpable put-on twang in the word “boy” in “A country boy gone city, blinded by its neon signs.” To commemorate Johnny Bristol Day, the lyrics to “Morganton” are printed in the local newspaper like a poem.

His honorary banquet, held at a neighborhood recreation center, is sold out in advance to an audience of 450—“everybody in Morganton was there that could get there,” says Brenda Brewer, who was on the alumni committee that helped organize Johnny Bristol Day. She still keeps her program among her Johnny Bristol LPs. “Whenever ‘Hang On In There, Baby’ comes on you wanna turn it up,” she tells me on the phone. “When my husband was still living, we’d put it on and you know, get to dancing around the kitchen! It makes you smile, makes you feel good, makes you remember.” Bristol’s banquet is sandwiched into days of touring local schools and institutions, giving interviews, a radio show. There are speeches, a custom-designed cake. Just before he receives the keys to the city, a pre-taped personal congratulatory greeting from Smokey Robinson plays for the hometown crowd.

At Olive Hill, the all-Black school from which he graduated, Bristol was a star football player and a tenor in the glee club (his voice deepened later) encouraged by his teacher Effie Williams. At Slades Chapel he sang in the choir, but he never learned to read music. “My parents never imagined anything for us but college,” John Fleming tells me. “If you didn’t go to college, you wanted to get out somehow,” says Calvin Johnson, husband of Bristol’s only sister, Barbara. Like Bristol, Johnson enlisted in the service: when he was in Germany, Barbara, called Nudie, who passed away this Easter 2021, went to live for a while with Johnny’s family in Michigan. “If you didn’t get out, you tried to get on at the hosiery mill or the furniture factory.” That I knew implicitly. My own parents were almost the opposite—though my father, Deaf from birth, had been a boarding student at the North Carolina School for the Deaf in Morganton, both he and my mother were from elsewhere in the state and had moved to town to teach and work at NCSD. Growing up, I never imagined staying. In “Morganton, North Carolina,” Bristol sings of his father, “we didn’t want for nothing, though his pay was small as hell.” In an interview in the local News Herald, Bristol painted a starker vision of his prospects: “If I’d stayed here, I’d probably be working down at Drexel Furniture, trying to make ends meet. That is, if I wasn’t in jail.”

Soon after he began working for Motown, Bristol married Iris Gordy, Berry’s niece, with whom he had another daughter, Karla, who has publicly pointed out that her father was one of the first Black musicians to take control of his catalog. Bushka Records blends the names of his three children—Johnny Jr., called Butch, Shauna, and Karla. Home for Johnny Bristol Day, Bristol buys the house he grew up in, renting it out to one of his brothers so it will stay in the family. Maybe he’ll retire in Morganton one day, he tells a local reporter. Calvin Johnson goes along with his brother-in-law to help him pick out a new car. “A 1975 red Cadillac,” Johnson remembers. It’s a Coupe de Ville, he tells me, with a matching interior and white seats. When he lived in Michigan, Bristol used to make the ten, eleven-hour drive between Battle Creek or Detroit and North Carolina. Now he goes all the way back home to buy a car made in or near Motor City. This time he’ll drive it all the way back to Los Angeles. He pays in cash.

Nearly twenty years have passed since Bristol graduated, went downtown and enlisted in the Air Force—a Rip Van Winkle space of time that contains the entire 1960s. He visits, returns for family reunions, but to reporters he calls his May 1975 trip his first real public homecoming. “I remember the kid who grew up here under heavy prejudice, and the two drinking fountains in town, one for whites and one for blacks,” Bristol says in one interview published in the local paper. “The kid who always had to go through the back door.”

When Bristol was playing gigs at the Bloody Corner, civil rights sit-ins had reached Burke County, North Carolina. It was after Greensboro, John Fleming remembers. The transformational Woolworth’s sit-ins by students from SNCC and NC A&T University continued from February to July; and sometime after, SNCC organizers fanned out in cities and towns throughout the state to educate and organize. “Some of them came to Olive Hill and they gave us some training in nonviolent action,” Fleming says from Ohio, where he and his wife have lived for forty-one years. “And I remember distinctly when we were talking about how to respond, and one guy said, Well, he wasn’t going to let anybody hit him or spit on him or pull anything on him. And so they told him that he could not participate, if that was going to be his response. He had to be ready to take whatever came.”

On the day of, Fleming recalls, “about a dozen of us walked to the Woolworth’s on West Union Street and sat down at the counter.” Fleming was a junior at Olive Hill and president of the student council. “I’m still surprised we were able to keep it a secret,” he said. “We decided we would just quietly sit there and wait to be served or denied service.” After five days, he said, city officials asked them for a moratorium, while they held meetings. “And we were reluctant to do that, because we thought we had developed some momentum and we were prepared for sort of a lengthy struggle. But we did give them the weekend. Within that week, they said everything would be integrated.”

This is the first I’ve ever heard of a 1960s sit-in in my own hometown—and I sit in Brooklyn stunned at both their bravery and the dedication and organization of SNCC, to go out and empower all these little places. “You know, there might have been an article written once things were integrated, but if I remember correctly—and I used to sell papers for the News Herald—that week that the sit-ins occurred, I think there was a blackout of news about them. I think they were keeping everything as quiet as possible,” Fleming says.

When I call Fleming’s classmate Brenda Brewer again, she concurs. “I wasn’t part of the group that was designated to take a seat, but there was a bigger group of us who walked downtown with them.” She doesn’t remember any threat in the streets, “but the folks that sat down inside, I don’t know. I believe there may have been some words or gestures that were exchanged, but I know they didn’t get service.” She also doesn’t recall being scared, or nervous that day: “All I remember was being young and foolish and fearless.”

A 1960 editorial published in the News Herald after Greensboro asserted, bewilderingly, that local sit-ins could lead to “a blot on Morganton’s record and set back the cause of improved race relations by more than fifty years.” This was published four years before the forced integration of local schools and fifteen years before Bristol’s homecoming.

And still. I mention to Calvin Johnson something else Brenda Brewer tells me she recollected hearing—how during that visit Johnny Bristol had allegedly been stopped by the Morganton police, in the parking lot of Roses discount store. “Yes, that did happen,” Johnson says. “Johnny Bristol got pulled over on Johnny Bristol Day. He was on his way to get the keys to the city when they stopped him in that red Cadillac for no other reason than being a black man driving it. On his way to get the keys to the city. I think they did issue him an apology.”

Johnny Bristol drives his red Cadillac back to Los Angeles, where through the late ’70s and ’80s he continues to make music—his own, Bristol’s Crème, Strangers, and Free to Be Me, and singles released around the world in the ’90s. By 2004, he’s back in the Battle Creek area, at work on a still unreleased gospel album when he dies suddenly at home, of an apparent seizure. “My wife was always on him to go to the doctor and get himself checked up,” Calvin Johnson says. “Johnny always said, if it works, don’t fix it.”

Bristol does not remarry after his second divorce, but if online forums are to be trusted, he is certainly not alone near the end of his life. On the site Blog of Death a commenter identifying herself as Marilyn scripts a movie scene of a memory, when (her original in all caps) “you jumped out of your Land Rover at the traffic light. Walked back to my car with an expression on your face that surely said ‘You are all that matter right here and now,’ placed the most passionate kiss on my lips. Then strutted back to your truck just in time for the light to change.”

Another poster, Connie, who writes of a sixteen-and-a-half-year relationship with Bristol, magnanimously acknowledges “all those other women who were blessed with [his love] as I was and still am...He made the women he loved feel special.” Mixed in with memories by Marilyn and Connie and barbs from a defensive “unknown” are testimonials from a former lawn mower and aspiring musician for whom Bristol once gave a preview of his never-released gospel album. Another arrives from producer Lamar Thomas who wrote a song for that same final, unfinished album, and who has since died. There are tributes from the faraway fans who grew up in homes “where [M]otown was always on the lips of many of my aunts,” the fans who cite his “passionate and uncommonly endearing country twang style of singing.” They call out the songs by name: “You and I.” “Love No Longer Has a Hold on Me.” “Do It To My Mind.” “Memories Don’t Leave Like People Do.” They write, “Brother Johnny, bless me with your spirit!” They are joined by Fawn: “Johnny was a wonderful man, genuine, very kind, sincere, and compassionate about everything and everyone. He had no ego or conceit like Marvin Gaye and David Ruffin... The time I spent with him will always bring a smile and bliss whenever I’m feeling low. Johnny always knew how to make a woman feel beautiful by using his heart and mind and not just with what’s between his legs.” Daughter Karla Gordy Bristol, who is now a talk show host in Beverly Hills, responds to the thread three years later, diplomatically and with appreciation: “He gave a lot of love, and could have taught classes on how to treat a lady.”

I think about how Dick Clark asked Johnny Bristol, “Are you a romantic individual?” to which Bristol intoned, in that deep steady bass, “I believe in love...”

Album released June 1974 by MGM

Tired of Being Alone

It is the winter of 1969 and Al Green is back in rural Michigan after a gig in Detroit. He pulls into a motel to try to catch some sleep on the drive back to Memphis. The very word Michigan “can still make me shudder,” he recalls in 2000, but today he wakes before dawn, looks out across the highway at a landscape of frozen fields slowly taking shape as the sky lightens. “The morning was so pure, so beautiful that I wanted it to never end,” he writes. “But even as the thought came to me I realized that, with no one to share it sooner or later I’d grow tired of being alone, tired of being on my own.” And then he reaches for motel pad and paper and begins to write the lyrics to his first true hit song.

I think about convergences and overlapping maps, how two musicians born in the rural South ended up singing their first songs on the same bloody corner in Michigan, how they both found a way to transform the hollow, displaced feelings of Northern loneliness and homesickness into seduction and romance. When Bristol performs on Soul Train from his album Bristol’s Crème, his friend Smokey Robinson jokes to Don Cornelius that the song “You Turned Me On To Love” should be twenty-five minutes long. It’s music, Robinson emphasizes, to make love by.

The first time I hear “Morganton, North Carolina” I too am sitting far from home in the near equivalent of a hotel room in New York City, a very small apartment in Brooklyn, and it’s hard to believe anyone wrote a song about our town, period. We’re too far west to merit a specific small town shoutout in Petey Pablo’s “Raise Up,” so even though I claimed that song too back in 2001, the experience of hearing Bristol’s is part odd pride, part a little amazement. I’d never heard anyone romance our town, at least not anyone whom I felt I could trust, someone who could paint it in all its colors, and still underline the need to leave it.

Yes We Will, Yes We Will

Granted I grow up with one parent who doesn’t hear music, and both parents working extra jobs while raising us. So I don’t recall when I consciously become aware of Johnny Bristol. I simply absorb the music. Who doesn’t, after all, know the Temptations, the Four Tops, the Supremes? Maybe my sister and I see reruns of the jubilance of the Soul Train line dancing to “Love No Longer Has a Hold On Me” (1981). From the blacktop behind our elementary school where we shoot hoops and play foursquare and jump rope and slap down cardboard, we can catch sight of the rec center where Bristol’s sold-out banquet was held, but we aren’t told that story. When we jealously watch the older sixth-grade kids choreograph a dance to “Beat It” for the end-of-year music show, none of our teachers tell us that a man from our hometown produced some of Michael Jackson’s songs, and Jermaine’s and Janet’s. That some of the kids in our school are related to Johnny Bristol, some go to his church, some are friends of his family, some live right by Mountain View Rec.

In fourth grade in North Carolina public school—at least then—you learn state history. The rivers named for peoples who were removed, the Lost Colony, the first English child born in the newly settled colonies, no kidding. You learn the mountains, the Piedmont, the coastal plain; you commit to memory the names of the one hundred counties, the names of the places where tobacco and peanuts come from. You do not hear about your classmates’ uncles and grandparents’ sit-ins that happened in your own town, about your classmates’ aunts and grandmothers who fought in the ’60s to desegregate the other rec center downtown where now you all go roller skating every Thursday. You memorize the map, but you are not shown then how its roads connect to the ones you can imagine beyond, the ones you hear on the radio, see on MTV.

The building that once housed the El Grotto Lounge in Battle Creek was demolished in the summer of 2019. In Morganton, Johnny Bristol is buried in breezy, oak-dotted Olive Hill cemetery next to a kudzu ravine and a short distance from the railroad tracks, not far from the site of the school where he sang with his earliest group. His stone is steps from Etta Baker’s, the legendary Piedmont blues guitarist who lived most of her life in Morganton and played faithfully on her porch in relative obscurity for decades until her belated rediscovery. Etta’s legacy was keeping alive the ancient sounds of vanished worlds, chords that she’d learned from her father and made her own—a time traveler. Johnny Bristol’s musical legacy, I think, is wrapped up in escaping this place and taking it somewhere else, embedding it in all those soul and r&b records, in loving it and leaving and coming back, driving away in that brand-new Cadillac, charting and tracing all those paths again and again.