West Virginia Coal Works, 1949, color woodcut, by Blanche Lazzell (1878–1956). Courtesy Hirschl & Adler Galleries, New York. Photograph: Eric W. Baumgartner

Something Deeply Rooted

The Invisible Landscape of Breece D’J Pancake’s Milton, West Virginia

By Emily Hilliard

“I purposely forget where Breece’s grave is so I have to find it each time,” my friend Rick Wilson tells me as we climb the hill of the Milton Cemetery one crisp October morning in 2019. In the moment, I don’t understand why or how he could forget, and wonder if maybe he hasn’t been here as much as he says he has. The cemetery, bounded by a chain-link fence and overlooking a trailer park on one side, a row of two-story houses on the other, is small and unremarkable. It would be hard to misplace a grave here. I walk ahead and find it—or perhaps he lets me find it—at the crest of the hill on the left side, toward the back—a large rectangular tombstone spelling out pancake. On the ground is an unassuming plaque, next to his mother’s and father’s. It reads:

BREECE D’J PANCAKE

june 29, 1952 April 8, 1979

Later, I read in a Washington Post article that came out the year after Breece’s book was published that he had mixed the mortar for his father’s gravestone himself. After I take a few photos, I feel a bit awkward; reverent in the morning chill, unsure what to say. We walk away from the grave, not speaking until we’re a few yards away. Rick makes me take a picture of a road sign on the cemetery’s main road. He points it out from the back so I have to turn to see it. It says, dead end.

Breece Pancake was born in South Charleston, West Virginia, in 1952, and raised in Milton, West Virginia, then a town of about 1,500 near the Ohio and Kentucky borders. His father Clarence worked at the Union Carbide plant and his mother Helen was a homemaker, and, later, a librarian. As Breece’s two sisters were ten and twelve years older, he spent much of his childhood effectively as an only child, and enjoyed hunting, fishing, and fossil collecting. Classmates knew him as a loner, with few friends his own age—he considered his father his best friend. He began writing in elementary school, and from early on was fascinated with local folklore, legends, and traditional practices he’d learned about from Milton elders and transients passing through, often incorporating their ghost stories, tales of local hangings, and ballad forms into his writing. In 1970, he entered college at West Virginia Wesleyan in Buckhannon, but transferred to Marshall University in Huntington to be closer to his father, who had been diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. Upon graduating with a degree in English education, Breece had hoped to teach high school English in West Virginia, but could not find a job in-state. Instead, he landed one at Fork Union Military Academy in Virginia, and a year later transferred to a job at Staunton Military Academy (where one of his favorite musicians, Phil Ochs, had been a student).

Shortly after, on September 8, 1975, his father died. Then just three weeks later, his good friend and former Fork Union co-worker Matthew was violently killed in a car accident. These two tragedies dealt an extreme emotional blow to Breece. In a documentary about his life, Breece’s mother Helen remarked that Breece had hoped Matthew would be a pillar of support during Breece’s bereavement and said Matthew’s death “liked to kill that boy.” In 1976, Breece was awarded a fellowship to the University of Virginia’s creative writing MFA program. There he was known as a dedicated teacher and prodigious, diligent writer. Inspired by fellow West Virginia authors Chuck Kinder and Thomas Kromer who revealed and storied the lives of those on the margins, Breece developed a lucid, sparse, and rhythmic style, infused with sense of place—almost hauntingly so. His characters can read like archetypal ghosts destined to inhabit the specific places that formed them; like geologic features, they belong uniquely to the circumstances of their time and location as the world moves around them.

In 1977, Breece sold a story, “Trilobites,” to the Atlantic Monthly; it was published in the December issue that year and caught the attention of New Yorker fiction editor Daniel Menaker. On Palm Sunday, 1979, at the age of 26, Breece died from a self-inflicted gunshot. His collection, The Stories of Breece D’J Pancake, was published in 1983, containing twelve stories and a foreword by his teacher and friend, writer James Alan McPherson.

Rick has been telling me about his Breece Pancake tour of Milton—Pancake’s hometown and the basis for the fictional “Rock Camp,” where many of the stories in his collection are set—since we first bonded over radical politics and transcendental literature five years ago, during a fieldwork trip to interview West Virginia labor songwriter Elaine Purkey. We talked about the elements of folklore in Pancake’s writing—not merely the local stories and ghost tales, but the whole array of folkways he had absorbed from people in his hometown; the vernacular language and verbal art shared on porch stoops and hunting camps; the occupational culture of farmers and miners, truckers and riverboat men; the superstitions related to weather and livestock and babies cursed by the evil their mothers encountered while pregnant; and the foodways of sorghum cane boils, fish roe, and jars of moonshine. This tour, Rick tells me, explores the sites—old train depots and diners, hills and holler neighborhoods, bank steps and covered bridges—as well as the more atmospheric setting that inspired many of Breece’s stories, mixed with a few locations from his life and death. It is a mapping and narrativization of place and memory held by a few individuals here, namely Rick and his friend Robert Jackson, a childhood buddy of Breece’s. Their recounting of stories and retracing of steps has become their own folklore as vernacular stories transmitted through the oral tradition. Their honed narratives appear in other books and films about Breece on which they’ve advised, and circulate among the handful of people they’ve taken on the tour.

Breece’s stories are stunning and devastating—certainly worthy of focused study—but in this context I’m interested primarily in how Rick and Robert employ Breece’s life and his writing, which drew heavily from local tales and fading ways of life in his hometown, to evoke a sense of place that twines experience, narrative, and landscape. Scholar Kent Ryden refers to this particular pairing of folklore and story within a specific location as “the invisible landscape,” writing, “Folk narrative is a vital and powerful means by which knowledge of the invisible landscape is communicated, expressed, and maintained. In fact, the sense of place—the sense of dwelling in the invisible landscape—is in large part a creation of folklore and is expressed most eloquently as folklore.”

Rick, like Breece, is a native son of Milton and also a writer, though Rick would balk at my equating them. His work has mainly taken the form of nonfiction essays published on his blog and newspaper op-eds on social justice issues. He didn’t know Breece well—they met only a few times; Breece was closer to his older brother’s age—but Rick had watched with admiration and a little jealousy from back home in Milton when Breece’s stories were published by the Atlantic. At the time of Breece’s death by suicide, Rick was working at the public library with Breece’s mother Helen; she as a librarian, he as a custodian. Over the next several years, they became close, and he witnessed her bereavement, eased through her determined efforts to get Breece’s short-story collection published. She told him, “The day they put him in the ground, I swore I’d see his book published.” In 1983, it finally was. It has never been out of print since.

I first read the collection about two years before I’d moved to West Virginia in 2015 to take a position as the state folklorist, where I would direct the West Virginia Folklife Program, working to document, present, sustain, and support the diverse cultural heritage and living traditions of communities in the Mountain State. A friend whom I’d taught with at a literature program in the woods of New England lent me a copy, knowing of my interest in working-class rural American fiction with a strong voice and sense of place (we’d both taught and loved the work of Maine writer Carolyn Chute). But over time and without a geographic contextual foothold in which I could situate Breece’s stories, they had become garbled, bleeding together in my mind. Before the day we’d picked for the tour, or as Rick called it in an email, “Breece Day,” he’d instructed me to read the book again, and bring it with me on the tour. This reading was different. Maybe it’s because I now live just miles from Breece’s hometown within the “Chemical Valley” that I was on this read able to focus on the intricate craft of the storytelling, the raw tone that seems so expertly effortless. Breece’s stories feel like they were wrought from a single piece of wood, whittled and carved into being, with all the elements there from the start—an exercise in removal rather than construction.

Breece’s grave is not in fact the first location on the tour. Rick reserves that for the site of Breece’s childhood home, just yards from the I-64 interstate which began construction when Breece was five and finished when he was eight. His family’s home was torn down, and now a Wendy’s sits on the site. Without much to see there, other than travelers filling up on a coffee pit stop and locals getting their morning biscuits, we just whip around the parking lot, not getting out of the truck.

After visiting the graveyard, we drive through a neighborhood headed toward downtown. Rick points out Breece’s elementary school which is still the public school in Milton. I imagine most kids in Milton don’t go to school knowing a writer of some renown once walked the same halls, ate in their cafeteria, searched for fossils on the playground. We park at the public library, where Rick worked with Helen, and walk past a salon and auto body shop en route to Main Street. Our next stop is the café described in Breece’s most famous story, “Trilobites” (Rick says Helen pronounced it “trill-o-bites”), where the main character Colly sits, eyeing Tinker Reilly’s little sister and pining after Ginny, Colly’s girlfriend who left him behind for college in Florida. His angst manifests in his disgust for the café’s cups hanging on pegs, covered in dust, and the “crisp skeletons of flies” on the windowsill. Breece describes a typical small town soda fountain scene, the type of place you imagine today when the New York Times sets its latest rural poverty porn piece at a diner in a flyover state. But now it is a Mexican restaurant, East Tenampa, or it was, a Milton resident told me, until it was allegedly raided by ICE and shut down in 2017. The sign still hangs outside. I peer in the storefront windows under the red awning and see that most of the furniture has been moved out, but a few tables and pieces of kitchen equipment are scattered in the middle of the tile floor. I can imagine crisp fly skeletons, roasted by the sun through the large window panes.

We continue down the street to the old Milton Bank Building on the corner. It’s no longer a bank, and all but boarded up, with a NO TRESPASSING sign hanging on the door. Rick stops and takes a seat on the broad cement steps, telling me that this is where he used to smoke cigarettes as a teen, performing toughness. In a letter to the author of Breece’s biography, Helen wrote of her husband, “Bud was drafted on a low order number regardless of two baby daughters, while young single men loafed on the Old Bank steps.” The steps were a gathering place for “generations of Milton ne’er-do-wells,” and one of Breece’s favorite hangouts, where he would sit and listen to old-timers’ yarns. Breece uses the popular loitering spot in his story “The Honored Dead” as the place where the narrator William Haywood sits, waiting “for the sun to come up over the hills; wait like I waited for the bus to the draft physical.” Rick, who, like Breece was a Wobbly for a stint, says that the name William Haywood refers to the co-founder of the Industrial Workers of the World; later in the story the narrator recalls his grandfather telling him of his last strike in the mines, and references the “One Big Union.” Rick believes that for that story and “A Room Forever,” set in Huntington, West Virginia, Breece drew upon literature published by the Appalachian Movement Press, an independent leftist print shop based in Huntington from 1969 to 1979.

As we sit on the steps, I start to realize that even my second reading of the collection did not adequately prepare me for the detail of this tour. I hadn’t read closely enough. I do not remember the Old Bank steps, didn’t catch the William Haywood reference. To locate these stories here in Milton, Rick is effectively laying the text over the town like a map, animating what Kent Ryden notes is “the way in which history piles up on the land, of the way terrain absorbs and recalls history, of the way narrative is an unstated component of any map and thus of any landscape.” Rick has an insider’s knowledge of Milton, yes, but also of Breece’s Rock Camp stories he’s so carefully studied. The “history” piling up on the land is not just a general textbook history of Milton, but a vernacular history, filtered through Rick’s lived experience and his understanding of Breece’s life and writing.

Poet April Bernard writes about the delusions pilgrimages to writers’ homes operate under—that one might somehow be able to fully comprehend the psyche of a writer by merely visiting his or her former places of residence. “Here’s what I hate about Writer’s Houses: The basic mistakes. That art can be understood by examining the chewed pencils of the writer. That visiting such a house can substitute for reading the work. . . . That writers can be sanctified. That private life, even of the dead, is ours to plunder.” I understand what she means. It’s the same annoyance I feel when biopics of artists insist on painstakingly reconstructing on screen the exact words of the artist’s song or poem, as if inspiration always and only is the result of direct, literal experience. But that’s not what is going on here. Aside from not centering on the sites of Breece’s life (his house no longer being there to visit, anyway), Rick’s tour is rather a personal and intertextual recounting of the oral history of each place—what they are now, what they were then, and how they’ve changed since. The locations we’re visiting inform a reading of the stories, and, conversely, the stories illuminate these places too. The tour is not a literal or direct reconstruction, but a process of discovery, a dialogue between place, text, and people. I understand now why Rick wants to find the grave anew each time.

In a letter to a young playwright who was interested in developing a one-man show based on “Trilobites,” Helen told him, “As for your visiting Milton—it isn’t the town Breece grew up in, Ninety % of the people are gone we knew.” The fact that in the forty years since Breece wrote the Rock Camp stories, the places and context have drastically changed doesn’t subtract from this exercise, but rather enhances it. Breece’s stories are deeply engaged in the passing of time on multiple, simultaneous scales—a human lifetime, a generation, an era. Reading them now, here, feels like a fitting engagement with those timelines.

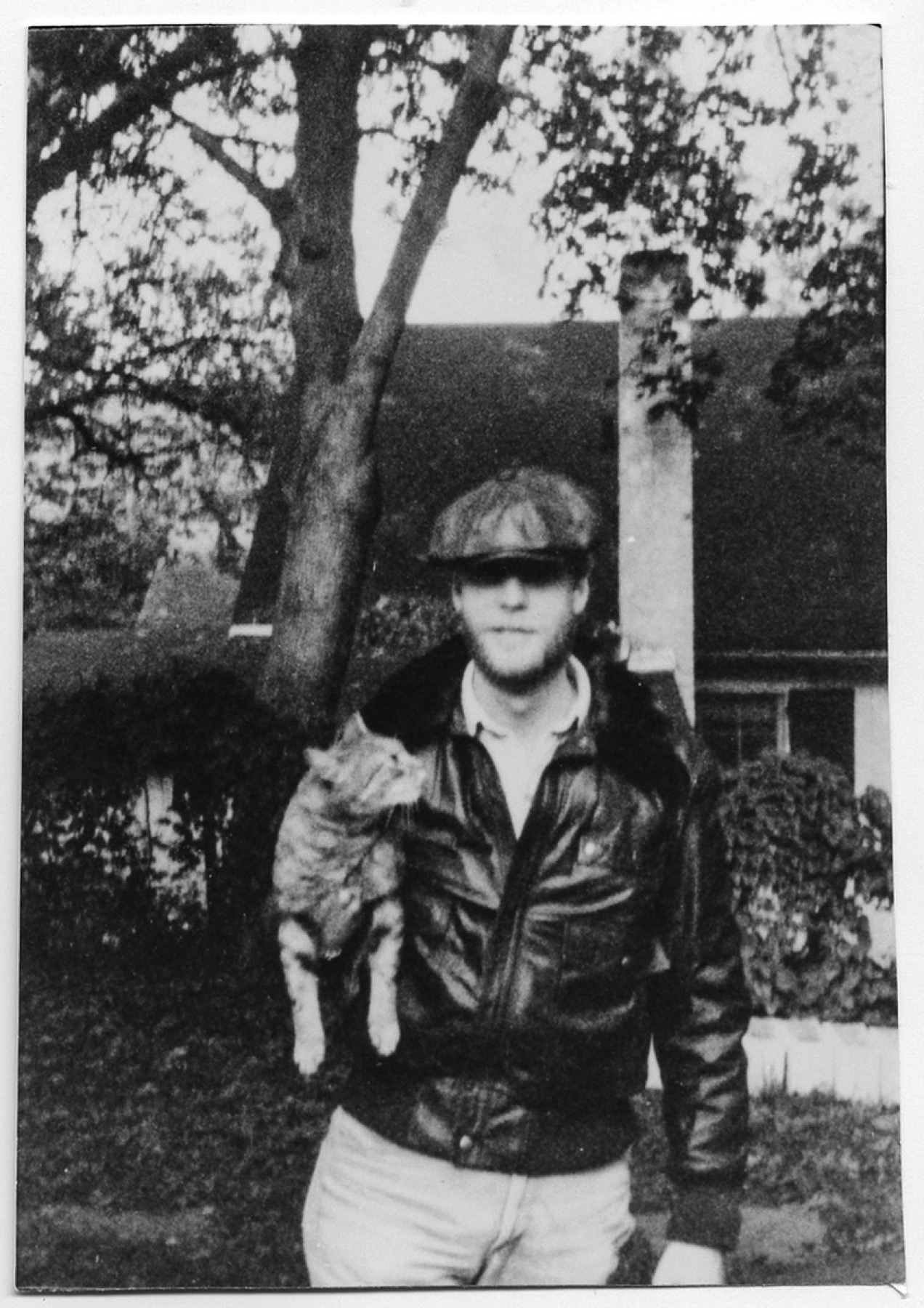

After I make Rick pose for a picture on the steps, we walk back to the library and go inside. A locked glass display case in the genealogy room is the only traceable evidence in town, aside from Breece’s grave, of his origins here. On the shelves are copies of the various editions of his short-story collection, the biography by Thomas Douglass, and framed photographs of Breece, captioned in an expert calligraphy and detailed, if quirky, intimacy: “This was made just before his father came down with M.S./ Breece was telling his father a story totally unaware this was snapped. Christmas 1970.” “Captain Breece D’J Pancake Teaching at Fork Union Military Acd. Fork Union, Va. 1974-1975. They made him shave his beard and he only wore glasses a short time.” “Breece D’J Pancake in Telluride, Colo., Aug. 1978 – When ‘In The Dry’ was published by Atlantic Monthly, he was well pleased.” I feel like I should linger here longer, but that’s all there is—Breece’s archival collections are held at West Virginia University and the University of Virginia. Rick takes me to the main reading room and shows me a picture of Helen, whom he worked with there every Tuesday and every other Saturday. “She was a storyteller—not exactly a gossip, but a collector of and elaborator on local stories,” he says. “You could see where Breece got it from.”

We get back in the truck and hit a few more story locations as a drive-by: the bridge in “The Honored Dead” where “Beck the Sport” fished with dynamite, ultimately blowing up himself and his ’51 Chevy in the process; the pool hall (now an Apostolic church) in “Salvation of Me” where Rick ate lunch in junior high school; and the river bank along the old high school sports fields (now a pre-K playground) where the covered bridge used to be. When the narrator of “The Honored Dead” gets kicked off the high school track team for draft dodging, he sits under the bridge, waiting for practice to be over. “Every car passing over sprinkled a little dust between the boards, sifted it into my hair. I watched the narrow river roll by, its waters slow but muddy like pictures I had seen of rivers on the TV news.” I don’t recall any of this from my second reading, and the covered bridge isn’t there anymore; it’s been rebuilt as “The Disneyland version,” as Rick calls it, in the city’s new Pumpkin Park. On the old site, the road just ends in the river, marked by a barricade so a car can’t accidentally roll right into the water. We drive along the bridge in “The Salvation of Me,” where there was “enough hump that hitting it at 45 would send us airborne every time and make the buggy rock like a chair until we could get new shocks on it.” Rick remembers doing this as a teenager, in pursuit of a cheap thrill, but the thrill is gone—they smoothed out the road several years ago.

More and more, we seem to not merely be retracing the inspiration for the settings of these stories, but mentally rebuilding them in their entirety—the childhood home, the pool hall, the covered bridge. Despite, or maybe because of, this impossibility, I find myself becoming even more invested in this challenge, the process of uncovering and recovering this town which even then Breece described as forgotten, a hold-over from a time more prosperous and hopeful. What’s happening, I think, is that Milton is becoming more of a “place” to me. Where it was once another town I passed by on the interstate, now it is vivified through an interpretation of Breece’s text, a vernacular narrative shared by Rick, and my own sensory experience, all rooted to a specific location; an invisible landscape, as Kent Ryden calls it, now annotates the physical landscape of this place. He explains, “For those who have developed a sense of place, then, it is as though there is an unseen layer of usage, memory, and significance—an invisible landscape . . . of imaginative landmarks—superimposed upon the geographical surface and the two-dimensional map.”

Breece’s stories feel like they were wrought from a single piece of wood, whittled and carved into being, with all the elements there from the start—an exercise in removal rather than construction.

We stop along the railroad tracks, where the foundation of an old building sits, overgrown with grass and saplings and covered in rotting wood pallets and other rubble. Though the building is no longer there, I recognize this from “Trilobites” as the boarded up old depot where Colly and Ginny break in, Ginny cutting her arm on a broken window pane. The depot was abandoned in the 1970s, after the hold the C&O Railroad had on Milton was eclipsed by other industries, oil and gas among them. When I go back to read the story again, I find mention of the gas wells, “pumps to suck the ancient gases,” in the “field sown with timothy” across the tracks.

“Breece saw the loss of industrialization coming right before it hit,” Rick says as we get back in the car. In the Rock Camp stories, “Trilobites” in particular, time seems to move on a metaphysical scale, slowly, in millennial increments. The story begins:

I open the truck’s door, step onto the brick side street. I look at Company Hill again, all sort of worn down and round. A long time ago it was real craggy and stood like an island in the Teays River. It took over a million years to make that smooth little hill, and I’ve looked all over it for trilobites. I think how it has always been there and always will be, at least for as long as it matters.

Colly searches for a fossil of a trilobite, one of the earliest known marine arthropods, but finds a gastropod instead. The age of the land and its slow movement are ever present in his awareness of place. He sees things—bison, ancient suns, old rivers, pterodactyls—that were once but are no longer. That reading and imagining of place, in place, is what’s required too on this tour—a stratified vision, with Breece’s life, layered over by what he knew of the land and this town’s history, stacked over his fiction, laid on top of what Rick has learned from reading and talk and Breece’s biography, presented now here to me, as we physically retrace each step. In Colly’s desperation and discontentment, that protracted approach to time is a comfort, a conduit for disassociation from the minutiae of his daily reality. The last line reads, “I feel my fear moving away in rings through time for a million years.”

Back in the truck, we head out to what Breece refers to as “Little Tokyo Hollow,” which appears in “Salvation of Me.” Rick tells me, “It has a bit of a reputation in the story,” and warns me not to take pictures there. “You might get Stranger with a Camera-ed,” he says. In this foothills neighborhood, peppered with trailers and small single-story homes, Rick feels like an outsider too, but mostly doesn’t want people to feel observed and uncomfortable. A three-legged dog follows our truck for a few blocks as we drive toward Colly’s anchor point, Company Hill, rising up over the holler.

We take the long way around back to town, driving past the Union Baptist Church, mentioned in “The Honored Dead,” where Union soldiers were garrisoned during the Civil War. Along a left-hand bend in the road we pass the construction site of the future Grand Patrician Resort, owned by Jeff Hoops, whose coal company Blackjewel LLC filed for bankruptcy in 2019 and stiffed employees out of their last two paychecks, spurring miners in Harlan County, Kentucky, to block the final shipment of Blackjewel coal from leaving town by train. Currently the Grand Patrician looks more like an old army barracks than the Greenbrier competitor Hoops aspires to; the austere stone building seems fitting for a Pancake story, but the ostentatious multi-columned classic revival luxury hotel does not. It’s hard to imagine it will ever be real.

Rick stops in a parking lot so I can snap a photo of the Rock Camp Road sign while he calls Robert Jackson to tell him we’re ready to meet for lunch. Robert, Rick tells me, was the inspiration for the character Chester in “The Salvation of Me,” which he says is the only funny story in the whole Pancake collection. He’s right, but even so, the comedy is brutally dark. Shonet’s, Milton’s greasy spoon, smells like fried apples, not from the actual fried apples they serve, but from artificial potpourri, overwhelming the air. Despite the strip mall setting, the place is cozy and packed to the gills with primitives. Robert has instructed us to snag a booth in the back where we can speak freely, so my recorder and mic don’t draw unnecessary attention. He comes in in a flurry, clutching a Xeroxed copy of “The Salvation of Me.” He’s flamboyant and warm, irreverent and hilarious, leading off with a childhood story about going fossil hunting with Breece and shitting his pants because they were too far away from a bathroom. He and Breece, both being towheads and about the same age, were often confused for each other in school and at the United Methodist church they both attended, but they ultimately led very different lives. Robert went to New York to pursue his acting dreams, but when his wife became pregnant, they moved back to Milton, where Robert worked as a banker.

Over our “Poorman’s Specials” of fried potatoes and beans and cornbread, Robert recounts the first time he read Breece’s stories: “Well, it was January and it was a bleak midwinter and Helen gave me a copy of the book and so I persevered [through it]. It was very, very depressing. Because I knew those people that he wrote of, those people who had no hope of ever having anything better than what he described. And I couldn’t think of anything that would help them.” About two-thirds of the way through the book, Robert came upon the story “Salvation of Me,” which begins, “Chester was smarter than any shithouse mouse because Chester got out before the shit began to fall. But Chester had two problems: number one, he became a success, and number two, he came back.” “It was obviously me!” Robert says laughing. As he read on, he realized Chester was not a very redeeming character. The resemblance weighing on him, the next time Helen came into the bank he asked her if he was Chester. “Yeeeeeeeeeasss,” Robert imitates her long drawl. He asked her if Breece really hated him, and she assured him, “Oh no, Robert, Breece loved you. That was the fiction.” As he sips his tea, Robert confides to Rick and me, “I always thought Breece—maybe he didn’t resent me, but I don't think he had a great deal of respect for the person that I was. I was more social, I enjoyed being with people, I also enjoyed being by myself. But you know, I could rally with the troops and I don’t think he could. And that might have been sometimes hard on him, since we had been so much of the same ilk as children, to see me be able to do some things socially that he did not want to do.”

Robert is both sympathetic and matter-of-fact—the years since Breece’s death have left clarity where there was once raw emotion. He shares that both he and Breece had alcoholic fathers, and wonders how that may have impacted Breece’s home life and upbringing. We talk about my job, and Robert and Rick catch up, updating each other on their wives and families and work. Rick teases Robert for leading with a story about soiled drawers, so Robert offers another example of his and Breece’s paralleled, then divergent paths. One Sunday afternoon when he and Breece were in high school, he was looking out of the window past the interstate at the hills outside Milton. He spotted Breece on the other side of the highway, climbing the hills into the woods, with a walking stick he had fashioned out of a tree branch. “He had a red bandana tied around his forehead, sort of like a sweatband, and an army fatigue jacket of some sort. That’s before it was cool to be walking around in army fatigues and camouflage, and I just looked at him up there and I thought, you are definitely marching to a different drummer,” Robert recalls. “Nobody was climbing the hillsides period, in their teen spells, and much less with a walking stick and a red bandana looking like something out of a history book from the 1800s. But this was the world he was living in and that’s where he enjoyed seeing himself as he crossed the great frontier,” Robert laughs.

We finish up lunch and Robert says he wants to take us to his church, where he and Breece were both members of the Methodist Youth Fellowship—Breece begrudgingly so. We park outside and walk into the sanctuary, now empty, quiet, and unlit, except for the sunlight streaming onto the curved pews and red carpet through the lancet stained-glass windows. Robert becomes contemplative, telling us that the last time he saw Breece, shortly before he died, was in that sanctuary during a Sunday service. “He was seated in one of the old oak pews, and he was under the huge stained-glass window that lends a golden light to this sanctuary. And I remember looking at him, and just thinking he looked almost . . . ethereal? You know how when you’re in a light streaming in, and the person sort of becomes diffused in the light? And I was struck by how much he had changed since the robust young boy I knew who was seventeen years old,” Robert confides. “And here he was ten years older and he did not look healthy, and he did not look happy. He looked haunted. And I didn’t know why, but I could recognize the difference, yes.”

Outside the red brick church, I take a picture of the two old friends, Robert dapper in sunglasses, blue jeans, and a button-down green gingham shirt, Rick in his red wildcat strike tee, khakis, and running shoes. Before we part ways, Robert gives me a burned DVD of a documentary about Breece, produced by a West Virginia public television station in 1989. A few days later, I watch it at home and see a younger Robert, recounting the same stories he told me, using the same turns of phrase: Breece in a red bandana and army jacket setting out for the hills, the “bleak midwinter” during which he first read the collection. Breece’s mother tells a story I’d heard from Rick, about how shortly before his death, Breece said he’d had a dream where he was hunting with his cousin, and every time they’d shoot a rabbit or deer, it would pop back up and run away again. She wonders, stifling a sob, if Breece in his delusion may have thought the same thing would happen to him after he shot himself. These are the same stories that appear in Thomas Douglass’s biography, and the issue of Appalachian Heritage dedicated to Breece. The anecdotes told by the handful of people left in Milton who knew him are surprisingly few, and have become codified through their retelling.

In a letter to his parents shortly after Breece started grad school at the University of Virginia, he wrote, “I’m going back to West Virginia when this is over. There’s something ancient and deeply rooted in my soul. I like to think that I’ve left my ghost up one of those hollows and I’ll never be able to leave for good until I find it—and I don’t want to look for it because I might find it and have to leave.” Rick and Robert say that Helen always held out hope that Breece would come back to Milton. Though Breece expressed this desire too, they believed it would never have actually been viable for him. “She wanted him to come back and write in the house where he grew up, with his old typewriter bangin’ around, writing his stories. And it was just a pipe dream. That was nothing that he could come back to,” Robert says. In the WPBY documentary, West Virginia writer Denise Giardina relates, “In a way, Breece never left West Virginia”; his writing is evidence that his mind was always here. In the pages of the “Trilobites” manuscript, Breece left a piece of notebook paper where he listed Milton locations he referenced in the story. Douglass writes, “He felt compelled to leave a trail, maybe for the same reasons he had written and rewritten his last will when he was in Charlottesville and jotted notes on the back of things he owned, instructing his mother or someone to ‘dispose’ or to ‘keep.’”

Helen did this too, I assume after Breece’s death. In a five-notebook-page document titled, “The Stories of Breece D’J Pancake – Locations + Life” she details the places and experiential details that inspired each story. For “Trilobites,” she notes, “Teays River bed, a prehistoric river once flowing from Kanawha through the valleys of Putnam and Cabell Co’s. into the Guyandotte and Ohio Rivers . . . The farm is where Breece first saw cane growing. Ginny was a former girlfriend of course creatively changed.” Some of these locations are depicted in the documentary—the Old Bank steps, the Rock Camp Road sign, Company Hill, the C&O Railroad tracks. When I go back to read the collection a third time, I realize that the graveyard that Breece describes in “The Honored Dead” is the one where he’s now buried—a transmutation from non-fiction to fiction turned material again. At the risk of sounding cliché, there does seem to be a specter of him left in Milton, one traceable when you’ve overlaid text on the place, heard of his walks along the hillsides, and retraced his pen strokes. It’s always a faint outline, diffuse in the light.

Adapted from Making Our Future: Visionary Folklore and Everyday Culture in Appalachia, forthcoming from UNC Press.