La Cancion de la Nena

An undiscovered guitar prodigy in the borderlands

By Vanessa Angélica Villarreal

Side One

I have only the faintest recollection of the Borders Apartments on Media Luna Road in Brownsville, Texas.

The landscape itself is more feeling than memory: the clay soil, the stubborn grass and tangle of palm trees, the wet, heavy air, the common brown ducks crossing and uncrossing la resaca behind the complex, the flatness of the Texas horizon, endless land upon which to labor. And within all that ordinary was us: my mother, father, and grandmother, a little knot in a nondescript apartment complex. It was designed for working-class transborder immigrants, the people I loved—day laborers, truck drivers, domestic, food, and grocery workers—and among them, my father, a 29-year-old musical prodigy at the foot of this country, in a place no one ever expects to find someone extraordinary. It was in that little one-bedroom apartment where my first memories formed while observing the life of the artist: the grind, the study, the promise, the obsessive repetition over inconsequential details, hours spent grappling with an invisible problem, interior and gigantic. Later, I would learn too of invisibility, of illegibility, of unsustainable years full of almosts, the quiet, volatile aftermath of failure.

I always come back to the same scene in that apartment. He sits on the edge of the bed to compose and work through songs, facing an amp, while I curl into his velvet-lined guitar case and listen. He cycles through a milk crate of felt-edged records, playing along, adding expressive flourishes to the lead. Purple Rain, by Prince. “Cause We’ve Ended as Lovers,” Jeff Beck. The entirety of Breezin’ by George Benson. I have called up this memory so many times I feel the gauze of fiction starting to overlay its details. But it is a memory so dear, I reanimate it against the heaviness of the present—my father, full of promise and possibility, years before the shell he would become, now shut away in my childhood bedroom in the graying light of ever-closed blinds.

I’m often asked to name the first poem or poet I ever loved, and the question always leaves me kind of stumped. Nothing ever comes to mind—I didn’t have many books growing up, and so to this day I have some anxiety around being well-read enough. I consider possibilities for the real answers: In Utero? “Amor Eterno”? The Nuyorican Poets Café anthology? And then it becomes clear: my literacy began in my family’s extensive catalogues of music, constantly playing in every household, from every genre on either side of the border. From Donna Summer to Juan Gabriel to Janet Jackson to Rocío Dúrcal to Charlie Daniels Band to George Strait to Queen to Little Joe y La Familia to Led Zeppelin to Grupo Mazz to Prince to Vicente Fernández, my childhood was steeped in music, populated by musicians. And what I experienced as poetry came first through the song my father wrote for me when I was two years old, a song whose melody is a turning helix in my blood, another way of speaking my name. Do you have a song like that, written for you? It is the rarest gift I have ever received. It created me.

I was born in McAllen, Texas, a border city in the Rio Grande Valley recently in the news as the site of Trump’s migrant child separations, where ICE’s tent cities turned to tent hospitals in the era of COVID. “The Valley” or “El Valle” to locals is the subtropical stretch of land between Brownsville and Eagle Pass at the southernmost tip of Texas where everything has two names: Rio Grande/Rio Bravo; Laredo/Nuevo Laredo; McAllen/Reynosa; Brownsville/Matamoros. The cities along the river are not distinct cities, but transborder metroplexes, split by language. And the people begin to develop dual identities as well, not just the English and Spanish versions of their names like my Tio Javier/Xavier, but even half–alter egos, like my Tio Joel who now goes by “George,” or migrants who change their names entirely upon arrival, untethering themselves from a certain fate.

Although much of what Gloria Anzaldúa wrote has been rightfully subject to critique, her observation of the U.S.–Mexico border as an open wound “where the Third World grates against the first and bleeds” persists because to this day, her scholarship gives us the language to describe the psychic ruptures of the border, the “emotional residue of an unnatural boundary [. . .] in a constant state of transition [where] the prohibited and forbidden are its inhabitants.” What she wrote about best was this in-between, how the border produces a racial terrain every day, and how the wound of the border is a spiritual wound that becomes embodied as a psychic rupture of displacement, dispossession, of many selves at inner war. For me, however, the border is an eraser, a haunted site of constant loss, swallowing a deep history that is disappearing, existing only in the memory of elders who leave us too soon.

El Valle is also a place of family, resistance, and tradition passed down in tiny trailer house kitchens and yards with miraculously resurrected trucks and flourishing chile bushes. Its people are overwhelmingly generous, hilariously witty, constantly reinventing language, food, fashion, music. The borderlands are, by design, a subculture difficult to explain to outsiders and snowbirds, partly because it is so totally ignored and invisible to the rest of the United States. On the other hand, over the years, the Rio Grande Valley has more than kept up with American pop culture, developing its own cultural giants and ignored contributions in response: The Johnny Canales Show, Freddy Fender, rock acido, Tejano, Chicano punk, La Onda Cumbiera, and conjunto norteño are just a few.

Mostly, it is a land of forgetting and the forgotten—like all southernmost places, a site of invisible labors done by invisible people, of colonial erasure and self-erasure, where historical bodies refuse to disappear from their children, and the dead have a way of sticking around. A place of joy and split and striving, it isn’t “a valley” in the geographic sense—rather than land between mountains, it is instead a place between myths, each country a reflection and metaphor of itself.

Not only did he have the looks, the sex appeal, and an ineffable cool, he was absolutely sick with natural talent.

This is the language my father uses: I was waiting to be discovered.

His is a story I’ve never seen on VH1 Behind the Music: Reynosa, Tamaulipas, 1966, Gilberto Villarreal, an eleven-year-old son of migrant laborers, learns guitar on his own, practices day and night, far surpassing his 10,000 hours of practice before he turns fifteen. While his parents are far away working las pixcas, or the fields, through sheer will, he manages to find Beatles and Cream albums and distortion and wah-wah pedals with almost no resources. He was not a rare mind dreaming in a place that suppresses dreams with debt and labor—what is rare is that he almost made it. Steeped in the corrido tradition—songs farm workers would invent to pass on information, stories, and warnings about plantation life—he would let that texture of his life inform his craft, and make yet another contribution to American music from those who work the cotton fields, one that would go unheard.

Before SoundCloud and online demo submissions, “getting discovered” was the story musicians told each other about how the most famous acts of the day were plucked from obscurity on the basis of their talent. But mostly, that was a lie—the way into the music industry was either to be white and fit a formula, or to be part of a zeitgeist, a momentarily electric subculture that could be co-opted to reinvigorate the charts. Faithfully playing the clubs, booking small tours, and making a demo in the hopes a suit would show up to discover you was a far-fetched fantasy that everyone told my dad would happen to him—if anyone could make it, it was him. But no one, not even local labels, sent scouts to the Rio Grande Valley borderlands to seek out talent. In the seventies and eighties, if scouts went beyond New York and LA, they mostly sought out new rock talent in America’s post-industrial nerve centers, cities like Detroit, Minneapolis, Chicago, Nashville, and the deep South—places with a thriving Black culture, and white, English-speaking acts to reap the benefits.

Could the eldest son of migrant farm laborers, with only a secondary education from Reynosa, Tamaulipas, self-taught on a Sears and Roebuck classical guitar, playing rock and pop in Mexico and the transborder region, ever be what a major label scout had in mind?

Part of finding the next rock star, the next pop star, the next big thing, is sex appeal, usually determined by race, class, and desirability, which are not neutral factors. So-called “refined” facial features, light skin, cis-hetero performance, height, and weight are factors that signal which bodies can accrue wealth and which bodies are made abject and assigned labor. This has consequences, not only in the lives of laborers, but in how they see themselves depicted in a dominant culture. If the Rio Grande Valley is historically a site for laboring bodies, it is not a site Hollywood has any interest in, not even when the region gets the rare opportunity to represent itself. (See: actresses cast as Selena from New York or Los Angeles.)

I often wonder how America envisions the U.S.–Mexico border and its people, what desirability means when mapped onto the migrant body. My best guess is that the Rio Grande Valley and its people are not thought of at all, and if they are, it is as an undesirable region filled with undesirable people, a place of poverty, criminality, violence, detention centers, “border surges.” Desire, desirability, and undesirability are libidinal impulses, and if desire is the underside of belonging, it is central to the fate of the migrant. If labor is what makes us desirable, then what can this country do with whatever else we might have to offer? Headlines insisting that there’s a “surge at the border” exist only in the realms of colonial fantasy, where our fears, biases, and racial imaginaries determine the reality on display. The realm of fantasy informs not just laws and borders, who is defined as citizen, prisoner, or alien, but also popular culture, music, film—what we value reflected back as desire.

I’m reminded of a scene in Game of Thrones when Oberyn and his paramour Ellaria, visitors from the hot southern kingdom of Dorne, are introduced in the main brothel in King’s Landing, city of the royal seat, to underscore their foreignness via their deviant and insatiable sexual appetite. As they consider the women on offer, Oberyn, a handsome olive-skinned bisexual prince in his forties, is coded as the Latin lover archetype: a gallant masculine sexuality defined by excess, eroticism, exoticism, and danger. As he contemplates a fair-skinned, slender, nervous young sex worker, he smiles and says, heavily accented, “Look at this one. How lovely is she?” The sex worker is visibly anxious at his attention, the unspoken tension of the scene underscoring Oberyn’s aberrant sexuality, too much for even the brothel to accommodate. Ellaria, curly haired and bronze-skinned, leans back with a wine goblet, unthreatened. She nods in agreement and says, “Beautiful. But pale.” As he slides the young girl’s dress down, Oberyn replies, “They like them pale in the capital; it shows they don’t work the fields.”

This scene emphasizes Oberyn and Ellaria’s ethnic markings via their accents, skin color, and pansexual appetites as something aggressive, to be feared. But the scene also shows a shift in social station in the presence of whiteness. The southern prince comes from a far southern place of fields, and his desire becomes a menace in the presence of whiteness in a city that produces nothing but culture, politics, ideas, and status. The fields are far from King’s Landing, and we only imagine the laborers. Desire is mapped onto the delicate, slender white body that has not darkened working the fields, and whiteness is mapped onto first-world cities where things happen because the beautiful white people are there. So if the Rio Grande Valley and the transborder region is a land of fields, an area populated mostly by non-white, primarily Spanish-speaking migrant laborers, who by virtue of their abjection scare white girls and live in cities routinely named as the “fattest,” poorest, least-educated cities in the U.S., why would any record company send a record executive looking for talent there?

The people who live in the Texas borderlands navigate a terrain of overlapping colonial systems, reality pushed and pulled across the border’s blade so much that it creates a rupture in time itself. On one side, modernity, and the “developed,” “fast-paced” United States creating the future; on the other, the “undeveloped” Latin America always a decade behind, with its “primitive” housing and “low-tech” manual laborers anchored in the past. Time runs differently on either side of the line, making the borderlands themselves a site of temporal dislocation, where even the people are excluded from modernity itself, thought incapable of the skills needed for the future. This is the condition of borderlands indigenous descendants, whose tribal ties have long been obliterated by colonization: stranded in space and time, with no memory of the past, they are also denied access to the future.

Futurelessness is a deliberate racialized condition, and necessary to produce invisible workers—temporary visa, seasonal labor, guest worker. Temporal dislocation and futurelessness create the ideal conditions for exploitable labor, a never-ending shift in an endless strawberry field, with no guarantee you can stay. Like “working the fields” in the scene above, “Strawberry Fields Forever” means something different for the people at the border—an invisible life sung by the most famous band in the world.

He says of his youth, “I was born in the wrong place,” speaking of the invisibility and remoteness of the Valley and its culture. Could the music industry, looking ever-forward into the future, looking to make a star, ever consider a place that’s not even part of modernity, or the future at all?

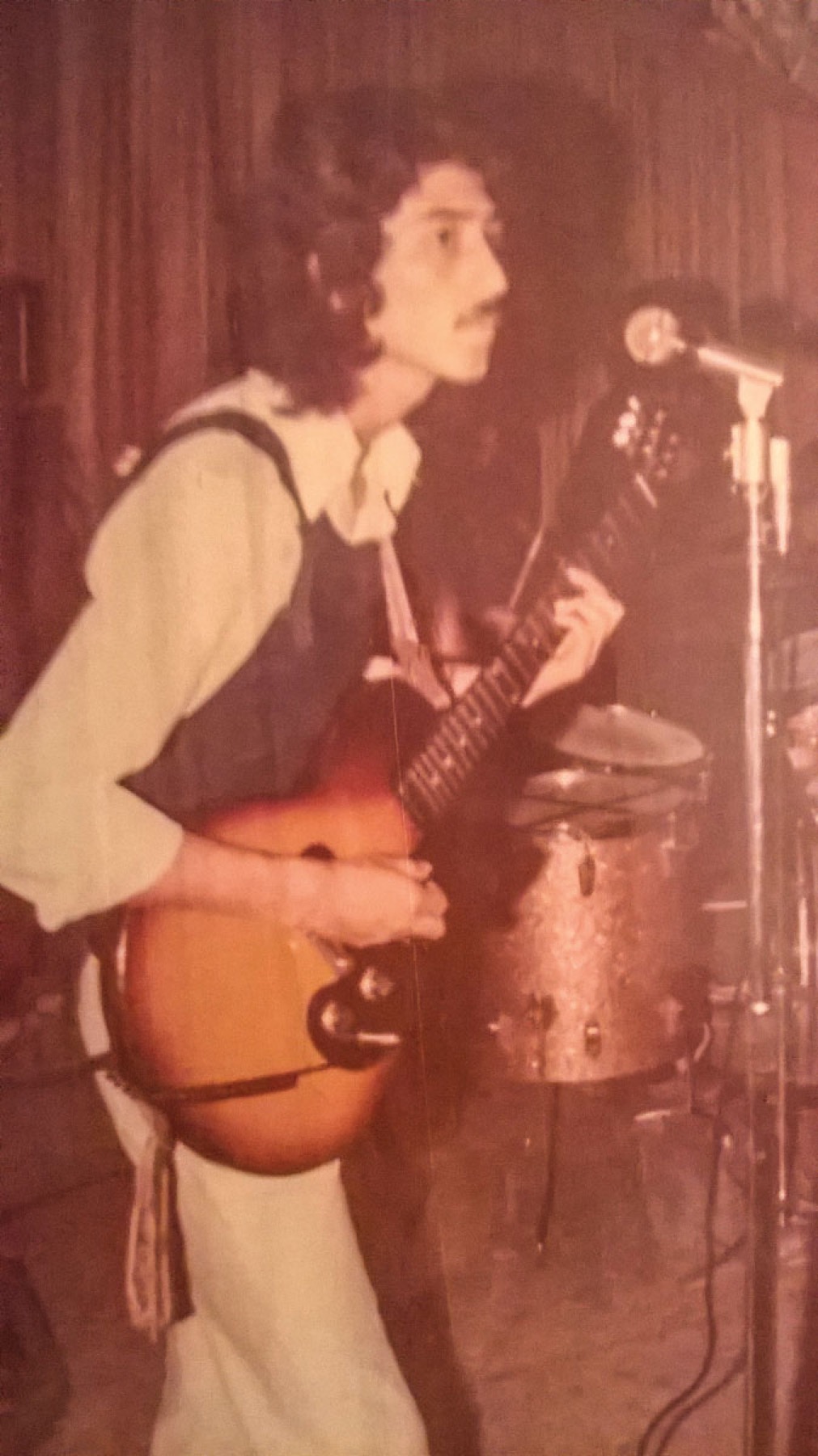

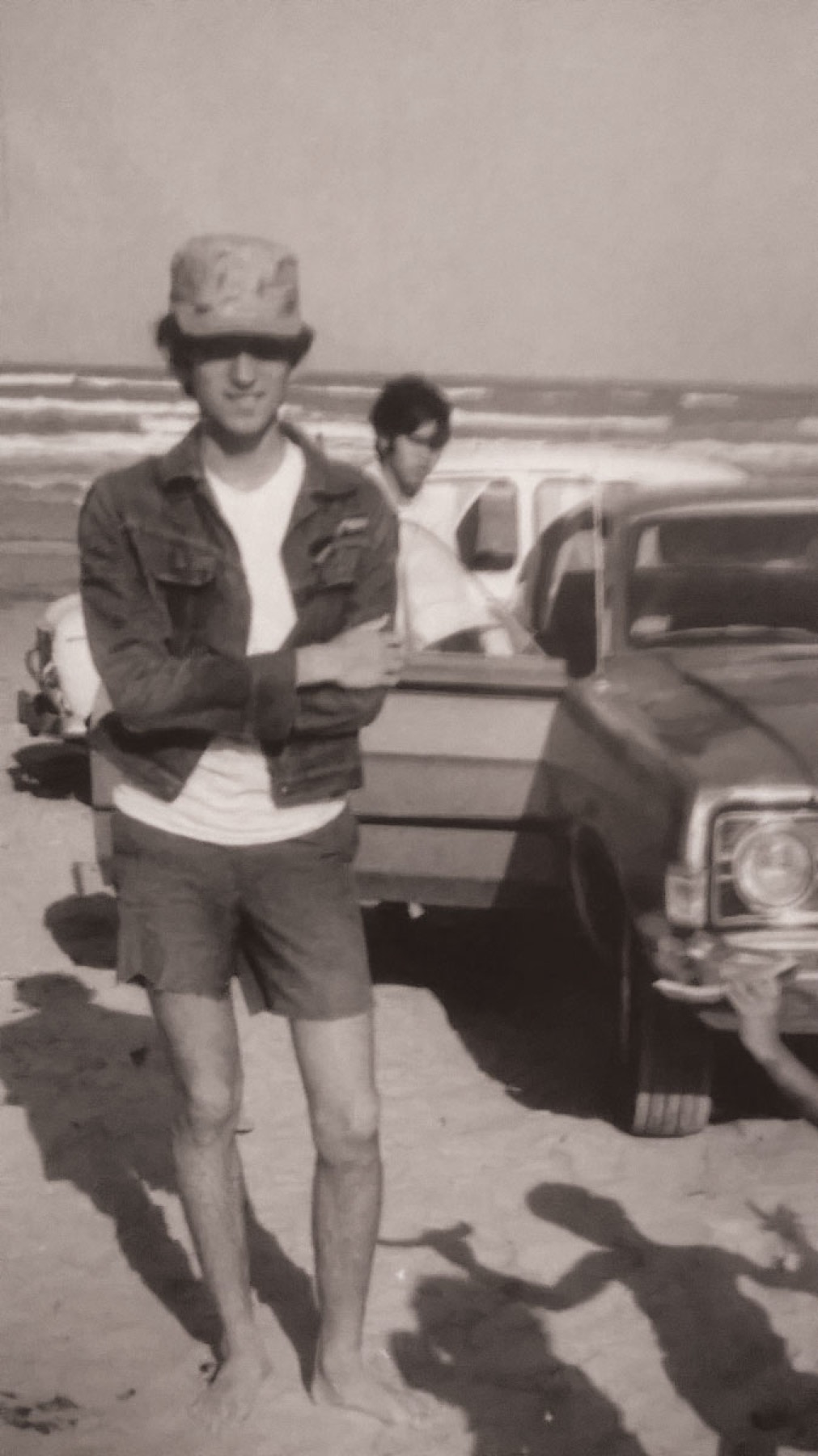

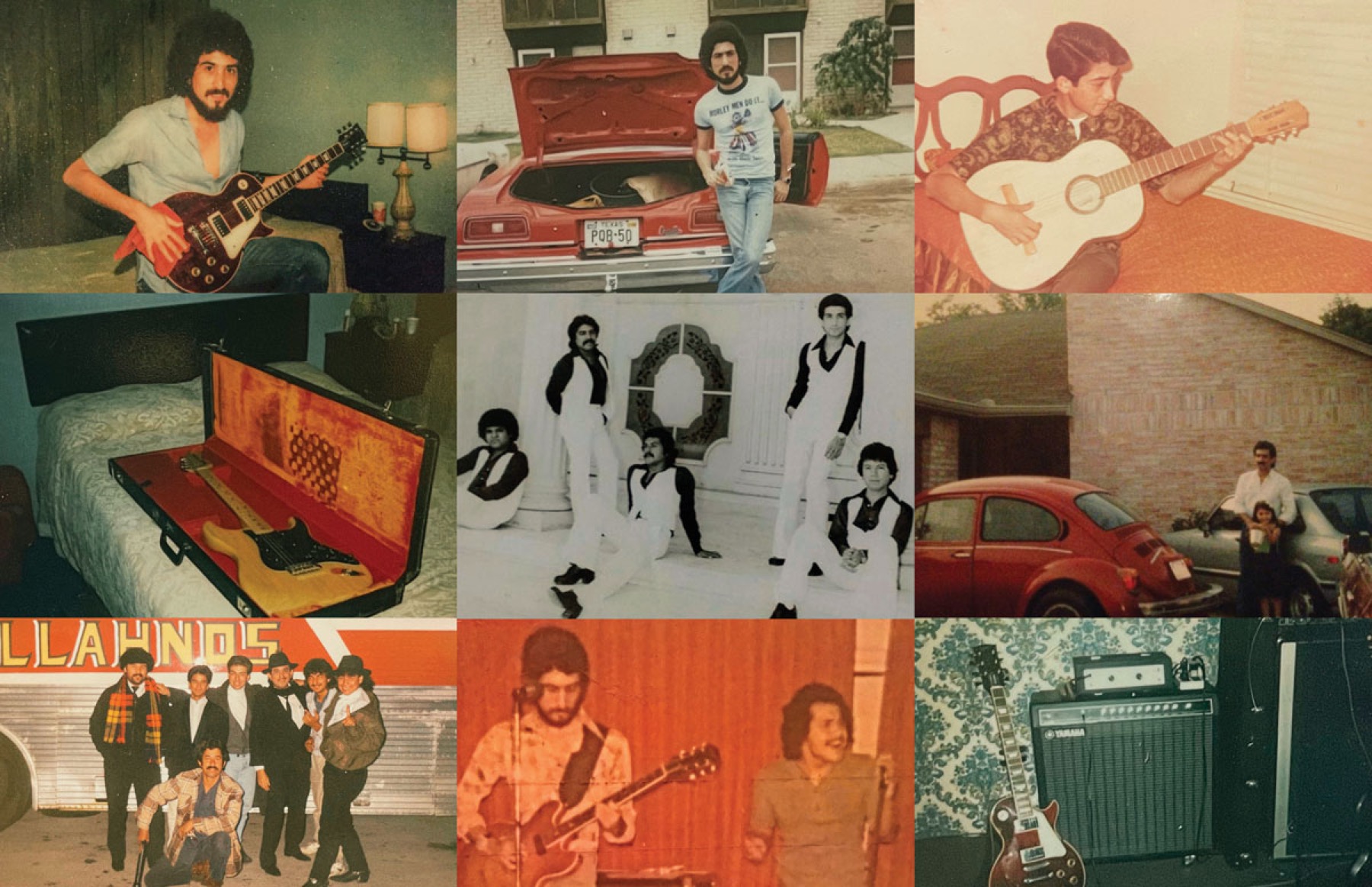

My father—swarthy, afroed, primarily Spanish-speaking—was never going to be what they were looking for, despite his good looks, talent, and carefully curated wardrobe. As the darkest-skinned child of five, and the eldest son, he was the least loved, and given so few clothes growing up that as an adult, he made up for it in elegance and stage presence, taking great care to dress well and in the latest fashions. Photos from this era show his studious but friendly nature, accented by a sharp personal style in bell-bottoms and ascots, velvet four-piece suits, tweed blazers, all the way to the white chinos and statement pastels of the eighties. He’s just one example of how chic and sophisticated Rio Grande Valley youth culture could be, despite humble origins. But no matter how beautiful he was, or how deserving his talent, he was on the wrong edge of the country. And perhaps it is this geographic, cultural, racial, and linguistic remoteness that developed my father’s rare gift into the expressive, but difficult, thing it became.

Side Two

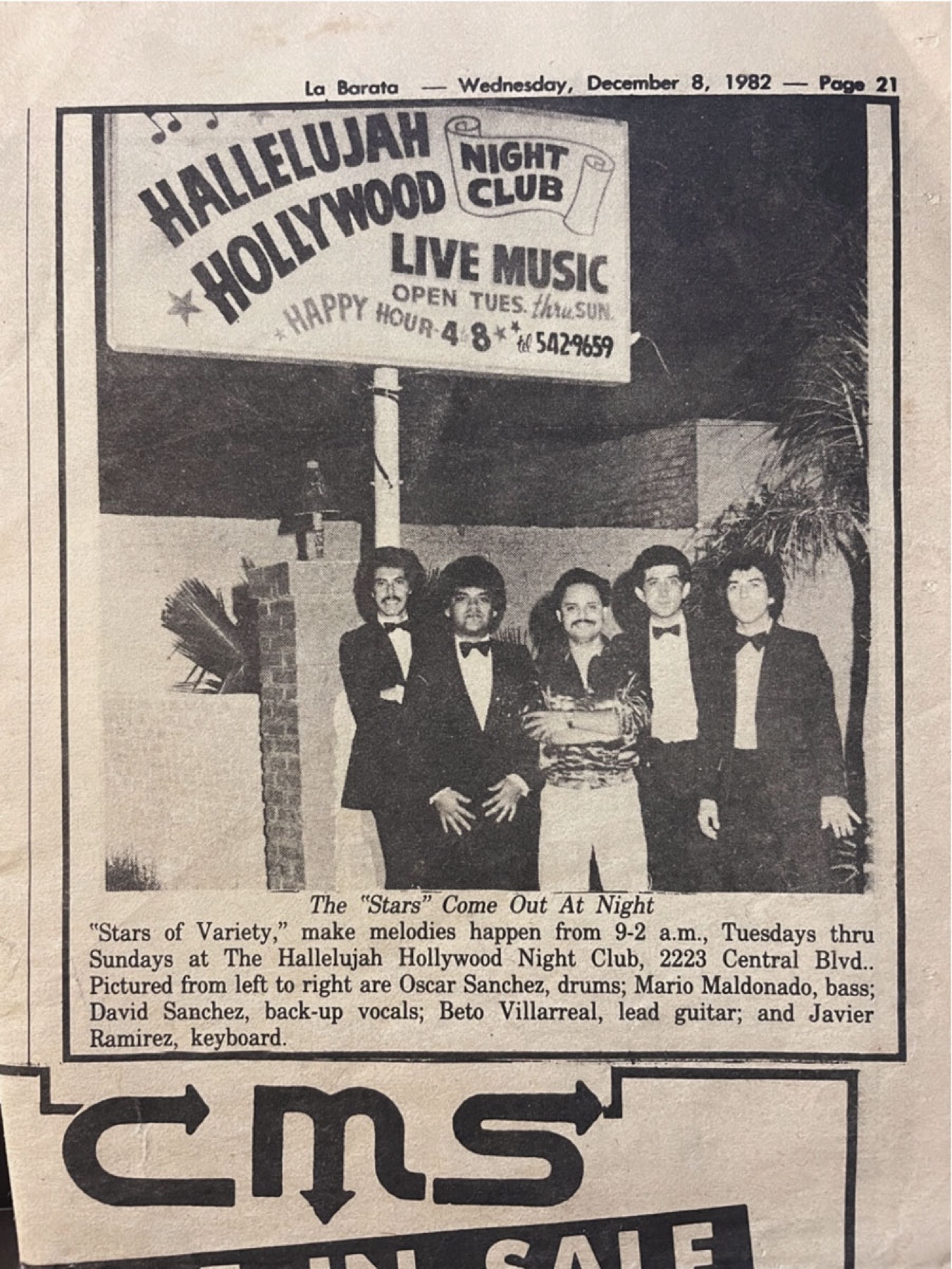

According to the community, it was only a matter of time before Beto Villarreal, La Maquina, the heaviest and most technical guitar player in Reynosa, would “get discovered.”

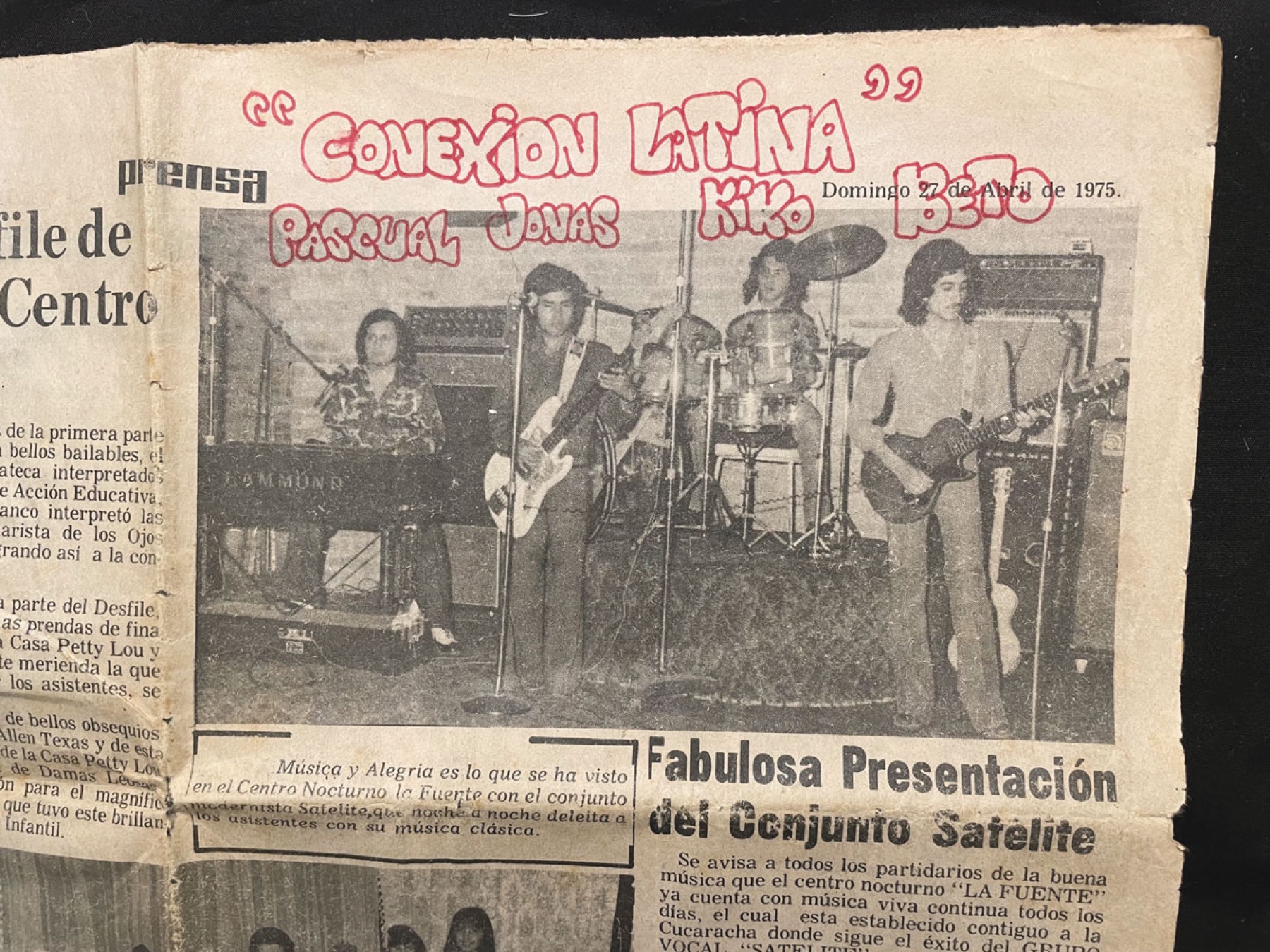

Not only did he have the looks, the sex appeal, and an ineffable cool, he was absolutely sick with natural talent. He began playing in multiple bands professionally in La Zona Rosa, a strip with nightclubs, bars, and other nightlife in Reynosa, starting at age fifteen with his first rock trio, La Maquina. Soon, the band came to be known as him—“Beto Maquina,” a kind of nickname to describe how hard he worked, how untouchable and singular he was. As his star grew, he joined the Reynosa acid rock group Canela India, a band that would go on to be recognized and honored in 2015 by the Reynosa Institute of Culture and Art as an important contributor to rock en español in Mexico and El Valle. Ever the black sheep of the family, his music began to strain his relationship with his mother, so one night, when she didn’t let him go out for a gig, he packed the only clothes he had—two pairs of jeans and a few shirts—in a backpack and ran away from home. And not just to the house of a friend, of which he had many. He bought a one-way ticket and got on a bus to Mexico City to follow his dream.

Once he arrived in Mexico City, his star shone bright and magnetic. He hooked up with friends and musicians, and almost immediately gained acclaim as the heaviest rock player on the scene. The music magazine Mexico Canta, the equivalent of Rolling Stone in Mexico, ran a full-page profile on him, highlighting the exciting new talent who at only seventeen was already being compared to prominent rock guitarists of the time like Eric Clapton and Jimmy Page. At the time, he resisted the comparisons because he didn’t think he was on their level. But now, after a life of playing jazz and learning music theory, he resists the comparisons for another reason:

Esos guitarristas eran como dioses, famosos, con unas guitarrotas hermosas. Eran lo máximo en ese tiempo. Pero ahora ya que se mas de la música y la guitarra, me he dado cuenta que no servían, casi no tocaban, no tanto como decían. Lo único que eran de Europa, eran blancos.

Those guitarists were like gods, ultra-famous, with these gorgeous expensive guitars. They were the pinnacle of rock back then. But now that I know so much more about music, I’ve come to find out that they weren’t all they were cracked up to be. They didn’t play as well as everyone said. They were just white, and from Europe.

He says that the guitarists who were much more technical, melodically richer, and more inventive were Black funk and soul players like those in Sly and the Family Stone, Ohio Players, Earth, Wind & Fire, and Funkadelic—artists who never got their “guitar god” flowers. As rock gentrified in the sixties, it became associated with the avant-garde, elevated as the genre of artistic genius and experimentation, associated with glamour and wealth, or country-fried in the South—claimed by the realms of whiteness. While rock guitarists gained individual renown and prestige, Black rock, soul, funk, and r&b bands of the sixties and seventies were not as solo-driven as rock & roll, nor were their guitarists often recognized as virtuosos. (That is, not until one of my dad’s favorites, Prince, came along.)

The week Prince died, I texted my dad to see how he was doing with the news, and to tell him I’d gone to see Purple Rain in the theater. He of course was sad, and as we talked through it, I told him about an interview Eric Clapton had done where the journalist asked him what it felt like to be the best guitarist in the world, to which he responded, “I don’t know, you’ll have to ask Prince.” My dad texts back, “Correctamondo.”

I never realized that while my father was young and playing rock throughout Mexico and in Mexico City, not just in small clubs, but at big events like the Jazz & Rock Benefit, the Mexican government had banned rock & roll following the 1968 Tlatelolco Massacre in Mexico City (recently portrayed in the film Roma), where the U.S.-backed authoritarian PRI regime massacred an estimated three hundred student demonstrators. Even before the massacre, in 1965, the Beatles were banned from playing in Mexico, and later the Doors and other big acts were, too. The Mexican government heavily censored all music and media, advancing a rhetoric of rock & roll as “immoral and not correct.” But the true fear was in rock’s role in gathering and organizing youth, its rebellious nature, and its ability to encourage radical politics, people power, and protest. Bands that did manage to put on shows faced shutdowns and police brutality—widespread bans followed a 1975 appearance by the U.S. band Chicago, which prompted a violent clash between civilians and police. So rock musicians and youth retaliated by creating venues called “hoyos fonkis,” or funky

holes—abandoned buildings, parking lots, warehouses—where rock music could go underground (sometimes literally), and a counterculture flourished under violent state repression and censorship. In the past, when he’s told me about his time with Canela India from 1971 to 1973, touring major cities in Mexico such as Cuernavaca, Acapulco, Mexico City, Jojutla, and Tampico, he never made it sound like he was part of a counterculture engaging acts of anti-authoritarian resistance. A life of humility and almosts has warped his memory into thinking he was never really part of anything big or culturally significant, but rather a player ever in the margins somewhere.

It is perhaps the violent, oppressive environment of Mexico and Latin America at large that never permitted rock & roll bands to become massive superstars like those from England or the U.S. Xenophobia, first world–third world relations, American racism, language barriers, and white supremacy made rock en español a hard sell to middle-American audiences. And there was certainly no Mexican equivalent to the star-making apparatus of the U.S. entertainment industry. U.S.–Mexico cultural exchange is very one-sided, extractive of resources, culture, food, and labor but never people, whereas Canada is a superstar and celebrity factory. So like many talented and beloved Mexican rock bands of the era, with no future in sight, Canela India broke up.

After an explosive year in Mexico City, still convinced he was a hot commodity destined for big things, with a magazine profile under his belt, my father decided to try his luck in Chicago for a year. He arrived in 1974, when Chicago’s Mexican-American and Latino immigrant communities were growing and working so-called “unskilled” factory jobs. Despite big dreams of finding his way into the funk and soul music circuit, it was difficult to secure his footing in the everyday world, much less the music world or the night life. Talent and originality alone don’t get you far in a new town, especially if that town is severely segregated by race and class like Chicago was, and continues to be. He got by working in a paint factory and made decent money, visiting clubs and attending shows when he could to try to connect to musicians. But after one year of no luck, it was time to come back to El Valle, to the river that calls back all its unwanted children.

Memory itself is a kind of map, linked to textures, smells, songs, places, the act of remembering in and of itself a kind of haunting.

My father emphasizes how closed English-speaking music scenes were to him. Looking back at his photos, I wonder how—I see a fashionable, elegant, handsome man, but with dark, ethnically ambiguous features and tightly curled hair—definitely not white, but not quite mestizo. He was an outcast in the land of outcasts, his unreal talent amplifying his already racialized otherness. I have asked and asked about Blackness in our family, and constantly come up against a hard blank wall of forgetting, of absence, only trace evidence and rumor combined with a history of the region that never produces a name—the mixedness of colonial subjecthood in the Valley.

Something about the combination of his features, his accent, and his lack of connections made auditioning for English-speaking rock and pop bands an exercise in constant alienation and rejection. He couldn’t simply arrive in any American city and start networking like he could in Mexico. And this negation began a seismic shift in his life, and a new pattern: a fiery spark of endless potential, and a letting go of the dream. He wanted nothing more than to play rock, but by 1975, the rock en español trend was waning and disco was heating up every dance floor in the Valley. Las discotecas del Valle are near-legendary in the region, sources of urban legends such as “Devil in the Disco,” a cautionary tale about a girl who went out on Good Friday and met a handsome man who made her dance all night to her death. This supposedly took place at Boccaccio’s in 1979, but throughout the ’70s, Valley folks bragged about sightings of legendary celebrities stopping at local restaurants and bars for one last night in the U.S. before crossing the border, and McAllen and Brownsville occasionally got big names to come through, like War, Santana, Javier Batiz (a legendary rock player from Mexico), and AC/DC.

One of those encounters could have been life-changing for my dad. In the late ’70s, he was playing with a band named Mister, or Etc., depending on which side of the line. This is another instance of the two-name problem in the borderlands: three of the band members didn’t have papers, so in the United States, they were Mister, and in Mexico, they were Etc. After a number of years establishing their reputation, the opportunity of a lifetime came knocking on the unlikeliest of doors: CHIC, one of disco’s greatest bands, was coming to McAllen, Texas, and Etc./Mister would open for them. My father remembers few details from the night, both a typical work night and an extraordinary occurrence. He remembers Nile Rodgers’s clear Stratocaster, and he remembers the band coming out to watch them open—something they ordinarily didn’t do. I asked him if he stuck around to talk to them and he said, no, they had to go to their hotel gig right afterward at the Hilton. But opportunity would seek them out again—while they were playing their set at the Hilton, CHIC and their management came to watch them play. They offered Mister/Etc. a permanent opening gig for the rest of the tour, but Etc.’s manager (a white Cuban, my dad points out) wanted too much money and in the end, no deal was made.

The reality of the music scene in South Texas in the seventies and eighties is one of hybridity, where the discoteca is also a taqueria and convenience store, and performances are also often family affairs, bailes organized around a quinceañera, or wedding, or child’s birthday. It strips legitimacy from serious performances, and anchors upward trajectories. One of these restaurant/nightclub and bar combos, Lalo’s, where one of my dad’s bands played steady gigs and my mother worked as a waitress, would be where my parents met. After they married in 1980, they lived in a small trailer house in McAllen, but eventually, with a child to support, circumstances would pull my mother away to work for a grocery store chain in Corpus Christi, and then away again to work in Houston, where my grandmother could receive cancer treatment. And the cycle would repeat again—opportunity to the North, labor pulling families apart, legacies of migration replicating themselves in new contexts.

He would continue to live in the apartment in Brownsville alone from 1984 to 1989 as my mother and I moved farther and farther north; he said he needed to stay there to maintain his weekly club and hotel rotation with his band Memories, and his bands were doing well, making money—they would soon “be discovered” and we wouldn’t have to worry about money anymore. I think, deep down, he believed another opportunity like CHIC would come along again, so long as he kept working. He came up to visit on weekends, until finally, when it was clear no one from Hollywood was coming, after no longer being able to stand the distance, he came to live in Houston with us.

My father sometimes says that if he weren’t tied down to a family, if he hadn’t moved to Houston, he would have “made it.” Mostly that’s wishful thinking, because it was the move to Houston that pulled him out of obscurity and put him right in the nucleus of La Onda Grupera, a busy hub for major Tejano and cumbia acts like Selena, and home to the legendary sax player Fito Olivares and his band. After working in roofing for a week or so, he auditioned for a new cumbia band, Los Super Villahnos, and got the position right away. They soon signed to Gil Records, an independent Latino music label, and began touring heavily, playing the baile circuit all along the southern states. It was their 1992 appearance on The Johnny Canales Show, however, that got them on the radio with their most famous single, “Vete.” Having a family was not a burden but a landing place between tours, major concerts, and television and radio spots—to him, however, this was his last shot.

And yes, he played with Selena: once on Johnny Canales while promoting his album Entregate, and once in 1992 in Laredo, Texas. And of his touring tales, he says this one is true: my father’s signature guitar, a white Fender Stratocaster, is a relic from the end of his Top 40 pop and rock days in the Valley. It was the most versatile between heavy rock solos and light pop rhythm guitar, and a piece he brought with him into the cumbia scene. When my father met Chris Perez, Selena’s guitarist and husband, who would go on to “blend cumbia and rock together” in Selena’s music and famously play a white Fender Stratocaster, Chris didn’t yet play a Stratocaster, nor did he have any solos. Hair metal had little organic audience in the Valley, so many rock musicians played in cumbia and Tejano bands to pay the bills. At that Laredo show, Chris saw in my dad an example of a rock player incorporating solos, using distortion, and adding rock flourishes to cumbia on his white Stratocaster. And from then on, Chris Perez would be associated with blending rock solos with cumbia, and with playing a white Fender Stratocaster. There are many stories my father tells me to hold back on—maybe they can’t be verified, or someone will have a different take on the same event. But about Chris Perez and the Strat, he says—this is one I can print because it’s true.

In the three years with the Villahnos, the band soared to great heights for the cumbia scene, opening for major acts like Bronco, Los Tigres del Norte, Selena, and Fito Olivares all across the U.S. and Mexico. He remembers playing shows with more than 20,000 people—the biggest crowd he ever played. Eventually, they caught the attention of Sony Records’s Spanish division in Chicago, and recorded their last album, Entregate, in 1993. Los Super Villahnos broke up due to circumstances beyond my father’s control, and to this day, they are played on the radio in Texas here and there, with fans still wondering what became of this great band and that one rola, “Vete.”

In 1993, the legendary sax player Fito Olivares had seen firsthand how my father ran sound for the Villahnos while playing the show. He’d been the band’s sound engineer, roadie, and guitarist all in the same night, and not only did Fito admire his hustle, he ran excellent sound. So the same week the Villahnos broke up, he began working for Fito Olivares as a sound engineer, his first ever W-2 job.

It is from here that my father’s luck would take a downward turn. With the death of my grandmother and the birth of my brother, he was under tremendous pressure to earn. He became the sound engineer for the renowned and successful Fito Olivares band, with the promise of a position as a guitarist in the band, a position he described as “having it made,” and a promise that never panned out. He began running sound for other bands on the bill for extra money, using Fito’s equipment. He would play jazz guitar at sound check instead of Fito’s recorded music. People at Fito’s concerts would recognize him from Los Super Villahnos or from his other bands in the Valley, and when he played guitar on the bus between gigs, it was clear he could run circles around any of the musicians in Fito’s band. Resentment began to build, and after five years, by 1998, he was out. No formal firing, they just never called him back.

Throughout the years, he would scrape together gigs here and there, and ended up playing bajo sexto for a Tejano/conjunto band called Sabiduria Norteña. The switch from guitar to a more traditional acoustic instrument was aesthetically very far from where he wanted to be, which was playing jazz and really showing his technical gifts, if even just to a tiny, intimate audience. But Sabiduria Norteña signed with Univision and recorded three popular albums. By then, in my twenties, I perceived my father as an adult. I could tell he wasn’t happy—he never discussed his work, or invited us to the performances, and he kept all of his stage costumes in the trunk of the car.

You might think from my tone that this is a sad story. And maybe it is, but it is also a tribute to an unseen life, a long overdue recognition of ordinary genius worn down by circumstance.

When I FaceTime my father one summer night to ask him the music theory behind the song he wrote for me, he casually shrugs his shoulders and says, no sé. No explanation, although I know there’s a meticulous understanding of every expression, a reason behind every note. Thirty-five years later, he still doesn’t understand how he wrote the song—he would only come to understand how complex it was later. The song spoke to an innate refinement in his musical ear at a young age, developed solely by

instinct—a complexity people write about in regards to Wes Montgomery or John Coltrane or Prince. He could explain the theory, the scales, the modes, but how he wrote it? That part is simply forged from the mystery of creation.

When I ask him about his writing process, he says only that one day, he became so overwhelmed with emotion upon seeing me, his infant daughter, that the song just poured out of him, fully formed—very unusual for my dad, who is a meticulous tinkerer and an exacting perfectionist when it comes to songwriting. The song he wrote for me back in 1984 remains untitled, referred to in my family only as “la cancion de la Nena,” or “the baby’s song,” a shorthand that betrays its tenderness and complexity.

The song itself is, from a music theory standpoint, technically intricate. Using jazz chords with shifting root positions to underlay a lead melody played at the same time, my father, a Mexican immigrant with an intermediate education, composed a song at 29 that impresses even elder jazz musicians, a song that would become our intimate musical language, able to communicate tenderness, regret, pride, absence, or forgiveness over the course of my life. Because I’ve listened to him play since my first day on earth, I’ve developed a sensitive ear. I can describe the slight difference in mood between an F minor 7th and a half-diminished chord, pentatonic vs. blues scales, Aeolian vs. Phrygian modes. And while melody, rhythm, and harmony come easily to me (I sing and taught myself guitar), growing up bilingual and lonely attuned my ear to the mood, rhythm, and music of language. Just as I have dozens of notebooks of old drawings and poetry, he has decades of staff notebooks, cataloging experiments in jazz guitar and music theory he’s written in light, precise pencil. He never had the means to go to school for music, so, as they are the sole record of a life of dedicated study, it hurts to see those notebooks now, stacked somewhere beneath boxes and cables in the garage—artifacts of an extraordinary mind to be forgotten along with every poster, promo, and album since he lost his vision.

I have only one recording of the song: a phone video recording a friend was able to capture from my wedding. It’s not as agile as the versions from my childhood, but it still captured the inventive chord structure, the deft lead, before my dad’s fingers would atrophy and make it hard for him to play. I barely remember the performance, and even though it’s mostly a happy memory, something about the document of that moment makes it too hard to watch.

Villarreal, far left, playing guitar for Rolando Becerra in 2011 at the George R. Brown Convention Center in Houston, Texas.

My father began to develop Type II diabetes in his forties in the early aughts after a life of touring, and since then, it’s caused significant nerve damage in his extremities and macular degeneration in his optic nerves. Diabetes is strongly linked to Latino communities, but it is more a disease of poverty, food deserts, and the demands of capitalism. His fingers and hands have atrophied, joints permanently bent, which has slowly made playing guitar painful, sometimes impossible.

These days, I try to lift his spirits by calling him on FaceTime. Has visto la nueva serie de Selena, Papi? No. Como te sientes, pa? Bien. Aver, tocame una de Wes Montgomery. No, mas tarde. Sometimes, when I ask him about his work, or his past, he’ll get a spark of energy and his old self will shine through with a story. But mostly, he stays in my childhood bedroom, door closed, lights off, surrounded by diabetes and blood pressure medications, pain pills he gets from a tio in Pasadena, and the tablet he holds inches from his face to watch YouTube jazz performances, stand-up specials, and, lately, conspiracy videos.

I feel an aesthetic kinship with other poets and writers who are also the daughters of musicians and wonder about our shared preoccupation with documents, sound, obscurity, and the artifacts of the past, ephemera and recordings and photos that are not to be catalogued or listened to, but stacked away in storage, under cables, motor oil, old towels, broken appliances. Every corner in my home is filled with relics like this, containing unknown histories—ranch life, Tampico high society, survival stories, family sagas—every artifact charged with haunting.

I think often of the CDs, tapes, promo posters, notes, sketches, and newspaper clippings from my father’s past as a professional musician, and the way in which these objects form an archive of failure and obscurity, never to be enshrined in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. The objects make me want to show the world what it missed out on, how invisible my dad was as a Mexican immigrant either playing rock and jazz because it was his passion, or playing cumbias and conjunto as part of an invisible community, rich with laughter and culture and drama. I’ve been able to recover some documents from the forgetting: his first televised performance on Johnny Canales, album covers, his first band Canela India’s homage at Reynosa’s cultural museum, artifacts I show in the short documentary film I made about his life. I think of Harmony Holiday’s collection Hollywood Forever, her own father’s similar obscurity, the enduring hit “Put a Little Love in Your Heart,” and how the documents of his career alongside old articles and ads weave themselves into the fabric of her work, let the historical contexts of the documents tell on themselves, reveal the pernicious racism and obscurity he lived through.

The body is a haunted terrain—a living record of personal, familial, social, and epigenetic memory. To look at my father’s body now—the way he shuffles when he walks, the atrophy in his once-nimble fingers, the nerve pain in his feet, the cloudiness in his eyes as he loses his sight—it too is a record of a forgotten life, and of the systems that failed it. I carry the memory of him in his splendor and his decline. And what I carry of him is also connected to the land, its seam connecting memory, legacy into the future. Memory itself is a kind of map, linked to textures, smells, songs, places, the act of remembering in and of itself a kind of haunting. Music is one of the few portals I have into my fragmented memory, and writing the only way I know to recover my people from the nothing of forgetting, to resist the erasure of the border and its constant overwriting of history, to salvage what is disappearing.

But already, this essay is engaged in the act of omission, forming itself into something to be archived, a thing of the past that, like the Valley, cannot imagine a future. So I will imagine this: Papi, you are on a stage, a sturdy stage with expensive lights and a roaring crowd. Your band, undefined by genre, is holding a note for you, the drums rumbling, and it’s up to you to deliver the solo that will take us home. Your body is not bent, or sick, or tired, but limber and alive. Your contributions to jazz, funk, disco, pop, rock, and cumbia are now legendary—the man who could do it all, an expansive career, who could cross geographic, racial, language, and genre boundaries and deliver memorable solos like Billy Preston—this immigrant, son of migrant laborers, not yet a citizen, captivating thousands. The show is an anniversary perhaps, or an induction. And you take it all in, give that smile everyone loves, and rip into a fiery solo, one that defines a career, and finally you are legible, visible, heard.