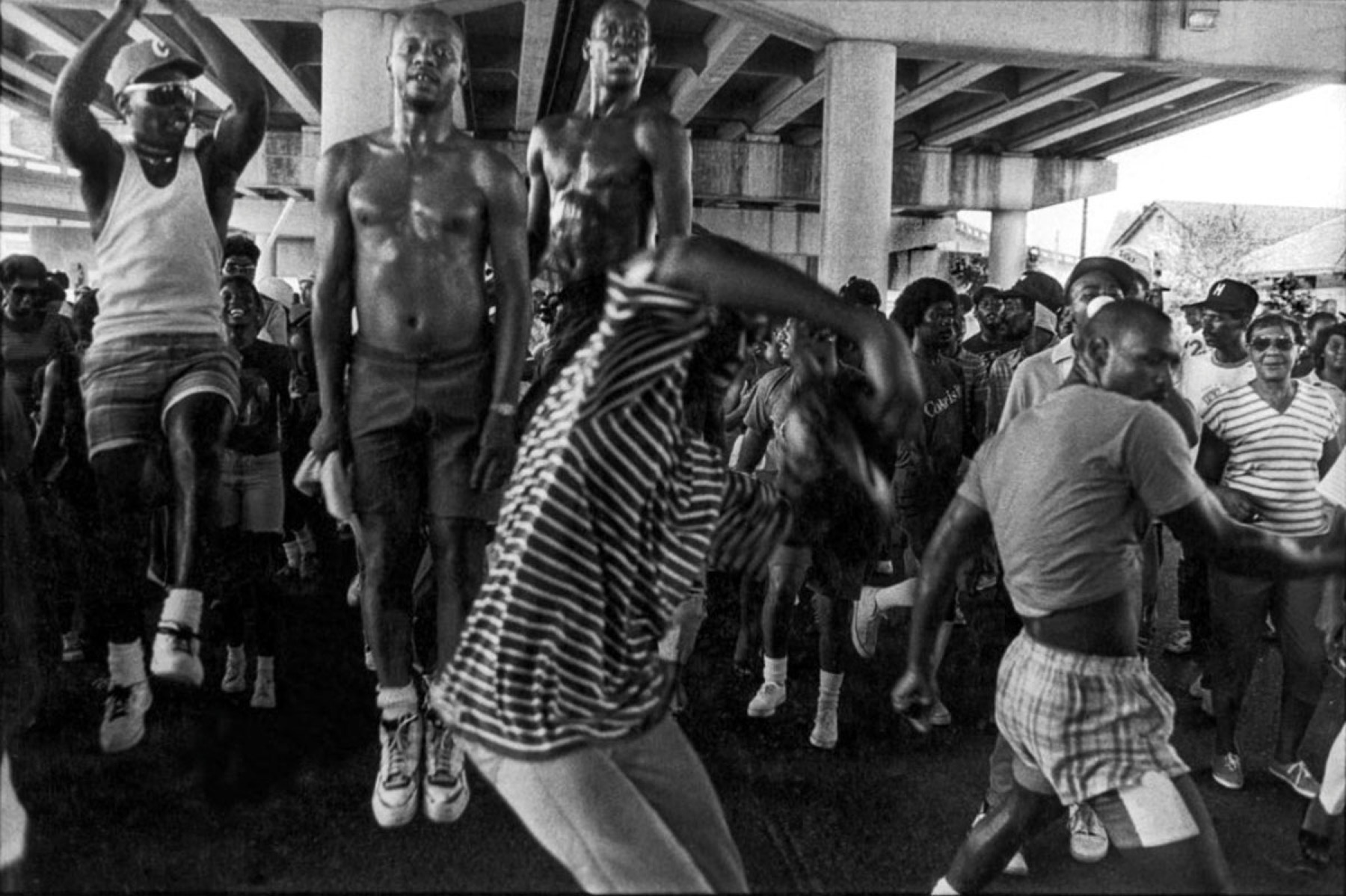

“Ascension,” by Chandra McCormick

The Art of Being Eaten Alive

By Channing Gerard Joseph

Everyone knows that you are what you eat. The age-old adage goes a long way toward explaining why American culture is so Black. For centuries—while America sustained itself on our blood—we built the Capitol, baked the cornbread, and birthed the culture. One of our most significant achievements was the cakewalk, a delectable dance form that we invented in response to being eaten alive.

In 1821, when a shipwreck destroyed the American whaling vessel Essex, the survivors resorted to cannibalism. The first four crewmembers eaten were Black. A decade later, in 1831, when slavers captured and killed Nat Turner, the leader of the famed Virginia slave rebellion, Turner’s executioners delivered his body to doctors for dissection. Then, according to William Sidney Drewry, a Virginia-born history professor, the physicians flayed the Black man’s corpse and used his skin to make a coin purse. Afterward, they boiled the remaining flesh to make grease. “The famous remedy of the doctors of ante-bellum days—castor oil—was long dreaded for fear it was ‘old Nat’s’ grease,” Drewry noted in his 1900 book The Southampton Insurrection, “and it is doubtful if the prejudice has entirely died out among the old darkies.”

Slavers, if they broke our will, bragged that we were “seasoned”—like all good food should be—so we might fetch a higher price at auction. At times, however, they literally seasoned us as a form of torture. Moses Grandy, a North Carolina slave forced to work on the Great Dismal Swamp Canal, testified in his 1843 narrative that we were “flogged and pickled” for failing to finish our ordained daily tasks. Pork or beef brine was poured on our “bleeding backs to increase

the pain.”

Frederick Douglass, the abolitionist and journaist, saw slavery itself as a form of cannibalism. Writing in 1845, he described it as a vampire, “its robes already crimsoned with the blood of millions . . . feasting itself greedily upon our own flesh.”

Trapped in the belly of slavery, Black people performed a kind of alchemy to survive: Through song and dance, we transformed our rage into rhythm, our sorrow into song. Where escape from bondage was not possible, the cakewalk gave us spiritual release.

Before we arrived from Africa, when we still were the Ashanti and the Dahomeans, an annual ritual gave us the freedom to mock our most revered leaders. In America, this tradition often expressed itself in a game of insults called the dozens. But where such direct confrontation with our oppressors was not viable, the cakewalk gave us a way to speak. In 1960, the actor Leigh Whipper related a story from his childhood nurse, who described the cakewalk like this:

Us slaves watched white folks’ parties . . . where the guests danced a minuet and then paraded in a grand march, with the ladies and gentlemen going different ways and then meeting again, arm in arm, and marching down the center together. Then we’d do it, too, but we used to mock ’em, every step. Sometimes the white folks noticed it, but they seemed to like it; I guess they thought we couldn’t dance any better.

The cake itself, bestowed upon the best dancer, was at first glance nothing to rhapsodize about. It was typically “a hoecake, baked in the hot coals of the hearth and wrapped in a cabbage leaf,” according to one 1892 account. But that hoecake, a mixture of water and cornmeal, literally cooked on the flat surface of a garden hoe, was a symbol of Black Americans’ ability to arise from the ashes, sweeter than ever.

While dancing the cakewalk, we sang improvised lyrics that were, as Douglass put it, “a sharp hit . . . to the meanness of slaveholders.”

We raise de wheat,

Dey gib us de corn;

We bake de bread,

Dey gib us de crust;

We sif de meal,

Dey gib us de huss;

We peel de meat,

Dey gib us de skin;

And dat’s de way

Dey take us in . . .

Seeing some glimmers of its real brilliance, whites in the United States and elsewhere moved to possess the dance for themselves. By 1902, white-owned theaters as far away as Paris were advertising the “true cake walk.”

Today, some of the essence of the art form can still be seen in the Soul Train dance, the New Orleans second line, and, in particular, vogue.

Since the slavery era, Blacks have been America’s sustenance, even as we ourselves went hungry. Without seeing this, it is impossible to understand the true significance of the cakewalk, which the Oxford English Dictionary simplistically defines as “a black Americans’ contest in graceful walking, with a cake as the prize.” A more accurate definition might be: a dance competition, born of Black genius and resilience, that enabled us to reap rewards from our white captors even as we scolded and ridiculed them to their faces.