Sweet Potato Pie

By Eugenia Collier

From up here on the fourteenth floor, my brother Charley looks like an insect scurrying among other insects. A deep feeling of love surges through me. Despite the distance, he seems to feel it, for he turns and scans the upper windows, but failing to find me, continues on his way. I watch him moving quickly—gingerly, it seems to me—down Fifth Avenue and around the corner to his shabby taxicab. In a moment he will be heading back uptown.

I turn from the window and flop down on the bed, shoes and all. Perhaps because of what happened this afternoon or maybe just because I see Charley so seldom, my thoughts hover over him like hummingbirds. The cheerful, impersonal tidiness of this room is a world away from Charley’s walk-up flat in Harlem and a hundred worlds from the bare, noisy shanty where he and the rest of us spent what there was of our childhood. I close my eyes and side by side I see the Charley of my boyhood and the Charley of this afternoon, as clearly as if I were looking at a split TV screen. Another surge of love, seasoned with gratitude, wells up in me.

As far as I know, Charley never had any childhood at all. The oldest children of sharecroppers never do. Mama and Pa were shadowy figures whose voices I heard vaguely in the morning when sleep was shallow and whom I glimpsed as they left for the field before I was fully awake or as they trudged wearily into the house at night when my lids were irresistibly heavy.

They came into sharp focus only on special occasions. One such occasion was the day when the crops were in and the sharecroppers were paid. In our cabin there was so much excitement in the air that even I, the “baby,” responded to it. For weeks we had been running out of things that we could neither grow nor get on credit. On the evening of that day we waited anxiously for our parents’ return. Then we would cluster around the rough wooden table—I on Lil’s lap or clinging to Charley’s neck, little Alberta nervously tugging her plait, Jamie crouched at Mama’s elbow, like a panther about to spring, and all seven of us silent for once, waiting. Pa would place the money on the table—gently, for it was made from the sweat of their bodies and from their children’s tears. Mama would count it out in little piles, her dark face stern and, I think now, beautiful. Not with the hollow beauty of well-modeled features but with the strong radiance of one who has suffered and never yielded.

“This for the store bill,” she would mutter, making a little pile. “This for c’llection. This for a piece o’gingham . . .” and so on, stretching the money as tight over our collective needs as Jamie’s outgrown pants were stretched over my bottom. “Well, that’s the crop.” She would look up at Pa at last. “It’ll do.” Pa’s face would relax, and a general grin flitted from child to child. We would survive, at least for the present.

The other time when my parents were solid entities was at church. On Sundays we would don our threadbare Sunday-go-to-meeting clothes and tramp, along with neighbors similarly attired, to the Tabernacle Baptist Church, the frail edifice of bare boards held together by God knows what, which was all that my parents ever knew of security and future promise.

Being the youngest and therefore the most likely to err, I was plopped between my father and my mother on the long wooden bench. They sat huge and eternal like twin mountains at my sides. I remember my father’s still, black profile silhouetted against the sunny window, looking back into dark recesses of time, into some dim antiquity, like an ancient ceremonial mask. My mother’s face, usually sternly set, changed with the varying nuances of her emotion, its planes shifting, shaped by the soft highlights of the sanctuary, as she progressed from the subdued “amen” to a loud “Help me, Jesus” wrung from the depths of her gaunt frame.

My early memories of my parents are associated with special occasions. The contours of my everyday were shaped by Lil and Charley, the oldest children, who rode herd on the rest of us while Pa and Mama toiled in fields not their own. Not until years later did I realize that Lil and Charley were little more than children themselves.

Lil had the loudest, screechiest voice in the county. When she yelled, “Boy, you better git yourself in here!” you got yourself in there. It was Lil who caught and bathed us, Lil who fed us and sent us to school, Lil who punished us when we needed punishing and comforted us when we needed comforting. If her voice was loud, so was her laughter. When she laughed, everybody laughed. And when Lil sang, everybody listened.

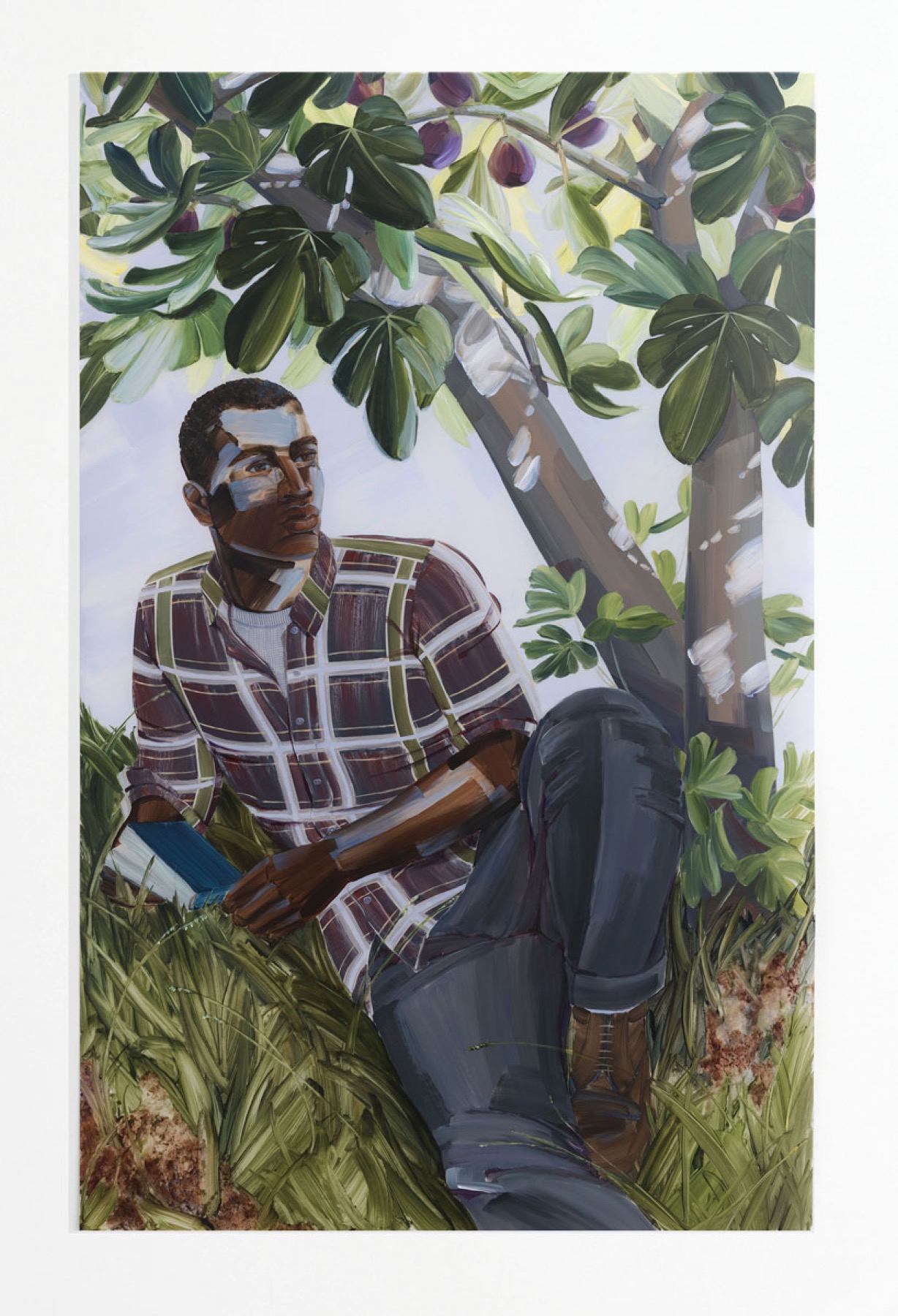

Charley was taller than anybody in the world, including, I was certain, God. From his shoulders, where I spent considerable time in the earliest years, the world had a different perspective: I looked down on the heads rather than up at the undersides of chins. As I grew older, Charley became more father than brother. Those days return in fragments of splintered memory: Charley’s slender dark hands whittling a toy from a chunk of wood, his face thin and intense, brown as the loaves Lil baked when there was flour. Charley’s quick fingers guiding a stick of charred kindling over a bit of scrap paper, making a wondrous picture take shape—Jamie’s face or Alberta’s rag doll or the spare figure of our bony brown dog. Charley’s voice low and terrible in the dark, telling ghost stories so delightfully dreadful that later in the night the moan of the wind through the chinks in the wall sent us scurrying to the security of Charley’s pallet, Charley’s sleeping form.

Some memories are more than fragmentary. I can still feel the whap of the wet dish rag across my mouth. Somehow I developed a stutter, which Charley was determined to cure. Someone had told him that an effective cure was to slap the stutterer across the mouth with a sopping wet dish rag. Thereafter whenever I began, “Let’s g-g-g—,” whap! From nowhere would come the ubiquitous rag. Charley would always insist, “I don’t want to hurt you none, Buddy—” and whap again. I don’t know when or why I stopped stuttering. But I stopped.

Already laid waste by poverty, we were easy prey for ignorance and superstition, which hunted us like hawks. We sought education feverishly—and, for most of us, futilely, for the sum total of our combined energies was required for mere brute survival. Inevitably each child had to leave school and bear his share of the eternal burden.

Eventually the family’s hopes for learning fastened on me, the youngest. I remember—I think I remember, for I could not have been more than five—one frigid day Pa, huddled on a rickety stool before the coal stove, took me on his knee and studied me gravely. I was a skinny little thing they tell me, with large, solemn eyes.

“Well, boy,” Pa said at last, “if you got to depend on your looks for what you get out’n this world, you just as well lay down right now.” His hand was rough from the plow, but gentle as it touched my cheek. “Lucky for you, you got a mind. And that’s something ain’t everybody got. You go to school, boy, get yourself some learning. Make something out’n yourself. Ain’t nothing you can’t do if you got learning.”

Charley was determined that I would break the chain of poverty, that I would “be somebody.” As we worked our small vegetable garden in the sun or pulled a bucket of brackish water from the well, Charley would tell me, “You ain gon be no poor farmer, Buddy. You gon be a teacher or maybe a doctor or a lawyer. One thing, bad as you is, you ain gon be no preacher.”

I loved school with a desperate passion, which became more intense when I began to realize what a monumental struggle it was for my parents and brothers and sisters to keep me there. The cramped, dingy classroom became a battleground where I was victorious. I stayed on top of my class. With glee I out-read, out-figured, and out-spelled the country boys who mocked my poverty, calling me “the boy with eyes in the back of his head”—the “eyes” being the perpetual holes in my hand-me-down pants.

As the years passed, the economic strain was eased enough to make it possible for me to go on to the high school. There were fewer mouths to feed, for one thing: Alberta went North to find work at sixteen; Jamie died at twelve.

I finished high school at the head of my class. For Mama and Pa and each of my brothers and sisters, my success was a personal triumph. One by one they came to me the week before commencement bringing crumpled dollar bills and coins long hoarded, muttering, “Here, Buddy, put this on your gradiation clothes.” My graduation suit was the first suit that was all my own.

On graduation night our cabin was a frantic collage of frayed nerves. I thought Charley would drive me mad.

“Buddy, you ain pressed out them pants right. . . . Can’t you git a better shine on them shoes? . . . Lord, you done messed up that tie!”

Overwhelmed by the combination of Charley’s nerves and my own, I finally exploded, “Man, cut it out!” Abruptly he stopped tugging at my tie, and I was afraid I had hurt his feelings. “It’s okay, Charley. Look, you’re strangling me. The tie’s okay.”

Charley relaxed a little and gave a rather sheepish chuckle. “Sure, Buddy.” He gave my shoulder a rough joggle. “But you gotta look good. You somebody.”

My valedictory address was the usual idealistic, sentimental nonsense. I have forgotten what I said that night, but the sight of Mama and Pa and the rest is like a lithograph burned on my memory; Lil, her round face made beautiful by her proud smile; Pa, his head held high, eyes loving and fierce; Mama radiant. Years later when her shriveled hands were finally still, my mind kept coming back to her as she was now. I believe this moment was the apex of her entire life. All of them, even Alberta down from Baltimore—different now, but united with them in her pride. And Charley, on the end of the row, still somehow the protector of them all. Charley, looking as if he were in the presence of something sacred.

As I made my way through the carefully rehearsed speech it was as if part of me were standing outside watching the whole thing—their proud, work-weary faces, myself wearing the suit that was their combined strength and love and hope: Lil with her lovely, low-pitched voice, Charley with the hands of an artist, Pa and Mama with God knows what potential lost with their sweat in the fields. I realized in that moment that I wasn’t necessarily the smartest—only the youngest.

And the luckiest. The war came along, and I exchanged three years of my life (including a fair amount of my blood and a great deal of pain) for the GI Bill and a college education. Strange how time can slip by like water flowing through your fingers. One by one the changes came—the old house empty at last, the rest of us scattered; for me, marriage, graduate school, kids, a professorship, and by now a thickening waistline and thinning hair. My mind spins off the years, and I am back to this afternoon and today’s Charley—still long and lean, still gentle-eyed, still my greatest fan, and still determined to keep me on the ball.

I didn’t tell Charley I would be at a professional meeting in New York and would surely visit; he and Bea would have spent days in fixing up, and I would have had to be company. No, I would drop in on them, take them by surprise before they had a chance to stiffen up. I was anxious to see them—it had been so long. Yesterday and this morning were taken up with meetings in the posh Fifth Avenue hotel—a place we could not have dreamed in our boyhood. Late this afternoon I shook loose and headed for Harlem, hoping that Charley still came home for a few hours before his evening run. Leaving the glare and glitter of downtown, I entered the subway which lurks like the dark, inscrutable id beneath the surface of the city. When I emerged, I was in Harlem.

Whenever I come to Harlem I feel somehow as if I were coming home—to some mythic ancestral home. The problems are real, the people are real—yet there is some mysterious epic quality about Harlem, as if all Black people began and ended there, as if each had left something of himself. As if in Harlem the very heart of Blackness pulsed its beautiful tortured rhythms. Joining the throngs of people that saunter Lenox Avenue late afternoons, I headed for Charley’s apartment. Along the way I savored the panorama of Harlem—women with shopping bags trudging wearily home; little kids flitting saucily through the crowd; groups of adolescent boys striding boldly along—some boisterous, some ominously silent; tables of merchandise spread on the sidewalks with hawkers singing their siren songs of irresistible bargains; a blaring microphone sending forth waves of words to draw passersby into a restless bunch around a slender young man whose eyes have seen Truth; defeated men standing around on street corners or sitting on steps, heads down, hands idle; posters announcing Garvey Day; “Buy Black” stamped on pavements; store windows bright with things African; stores still boarded up, a livid scare from last year’s rioting. There was a terrible tension in the air; I thought of how quickly dry timber becomes a roaring fire from a single spark.

They insisted that I stay for dinner. Persuading me was no hard job: fish fried golden, ham hocks and collard greens, corn bread—if I’d tried to leave my feet wouldn’t have taken me.

I mounted the steps of Charley’s building—old and in need of paint, like all the rest—and pushed the button to his apartment. The graffiti on the dirty wall recorded the fantasies of past visitors. Someone had scrawled, “Call Lola” and a telephone number, followed by a catalog of Lola’s friends. Someone else had written, “I called Lola and she is a Dog.” Charley’s buzzer rang. I pushed open the door and mounted the urine-scented stairs.

“Well, do Jesus—it’s Buddy!” roared Charley as I arrived on the third floor. “Bea! Bea! Come here, girl, it’s Buddy!” And somehow I was simultaneously shaking Charley’s hand, getting clapped on the back, and being buried in the fervor of Bea’s gigantic hug. They swept me from the hall into their dim apartment.

“Lord, Buddy, what you doing here? Whyn’t you tell me you was coming to New York?” His face was so lit up with pleasure that in spite of the inroads of time, he still looked like the Charley of years gone by, excited over a new litter of kittens.

“The place look a mess! Whyn’t you let us know?” put in Bea, suddenly distressed.

“Looks fine to me, girl. And so do you!”

And she did. Bea is a fine-looking woman, plump and firm still, with rich brown skin and thick black hair.

“Mary, Lucy, look, Uncle Buddy’s here!” Two neat little girls came shyly from the TV. Uncle Buddy was something of a celebrity in this house.

I hugged them heartily, much to their discomfort. “Charley, where you getting all these pretty women?”

We all sat in the warm kitchen, where Bea was preparing dinner. It felt good there. Beautiful odors mingled in the air. Charley sprawled in a chair near mine, his long arms and legs akimbo. No longer shy the tinier girl sat on my lap, while her sister darted here and there like a merry little water bug. Bea bustled about, managing to keep up with both the conversation and the cooking.

I told them about the conference I was attending and, knowing it would give them pleasure, I mentioned that I had addressed the group that morning. Charley’s eyes glistened.

“You hear that, Bea?” he whispered. “Buddy done spoke in front of all them professors.”

“Sure I hear,” Bea answered briskly, stirring something that was making an aromatic steam. “I bet he weren’t even scared. I bet them professors learnt something, too.”

We all chuckled. “Well anyway,” I said, “I hope they did.”

We talked about a hundred different things after that—Bea’s job in the school cafeteria, my Jess and the kids, our scattered family.

“Seem like we don’t git together no more, not since Mama and Pa passed on,” said Charley sadly. “I ain’t even got a Christmas card from Alberta for three-four year now.”

“Well, ain’t no two a y’all in the same city. An’ everybody scratchin’ to make ends meet,” Bea replied. “Ain’t nobody got time to git together.”

“Yeah, that’s the way it goes, I guess,” I said.

“But it sure is good to see you, Buddy. Say, look, Lil told me bout the cash you sent the children last winter when Jake was out of work all that time. She sure preciated it.”

“Lord, man, as close as you and Lil stuck to me when I was a kid, I owed her that and more. Say, Bea, did I ever tell you about the time—” and we swung into the usual reminiscences.

They insisted that I stay for dinner. Persuading me was no hard job: fish fried golden, ham hocks and collard greens, corn bread—if I’d tried to leave, my feet wouldn’t have taken me. It was good to sit there in Charley’s kitchen, my coat and tie flung over a chair, surrounded by soul food and love.

“Say, Buddy, a couple months back I picked up a kid from your school.”

“No stuff.”

“I axed him did he know you. He say he was in your class last year.”

“Did you get his name?”

“No, I didn’t ax him that. Man, he told me you were the best teacher he had. He said you were one smart cat!”

“He told you that ’cause you’re my brother.”

“Your brother—I didn’t tell him I was your brother. I said you was a old friend of mine.”

I put my fork down and leaned over. “What you tell him that for?”

Charley explained patiently as he had explained things when I was a child and had missed an obvious truth. “I didn’t want your students to know your brother wasn’t nothing but a cab driver. You somebody.”

“You’re a nut,” I said gently. “You should’ve told that kid the truth.” I wanted to say, I’m proud of you, you’ve got more on the ball than most people I know, I wouldn’t have been anything at all except for you. But he would have been embarrassed.

Bea brought in the dessert—homemade sweet potato pie! “Buddy, I must of knew you were coming! I just had a mind I wanted to make some sweet potato pie.”

There’s nothing in this world I like better than Bea’s sweet potato pie! “Lord, girl, how you expect me to eat all that?”

The slice she put before me was outrageously big—and moist and covered with a light, golden crust—I ate it all.

“Bea, I’m gonna have to eat and run,” I said at last.

Charley guffawed. “Much as you et, I don’t see how you gonna walk, let alone run.” He went out to get his cab from the garage several blocks away.

Bea was washing the tiny girl’s face. “Wait a minute, Buddy, I’m gon give you the rest of that pie to take

with you.”

“Great!” I’d eaten all I could hold, but my spirit was still hungry for sweet potato pie.

Bea got out some waxed paper and wrapped up the rest of the pie. “That’ll do you for a snack tonight.” She slipped it into a brown paper bag.

I gave her a long good-bye hug. “Bea, I love you for a lot of things. Your cooking is one of them!” We had a last comfortable laugh together. I kissed the little girls and went outside to wait for Charley, holding the bag of pie reverently.

In a minute Charley’s ancient cab limped to the curb. I plopped into the seat next to him, and we headed downtown. Soon we were assailed by the garish lights of New York on a sultry spring night. We chatted as Charley skillfully managed the heavy traffic. I looked at his long hands on the wheel and wondered what they could have done with artists’ brushes.

We stopped a bit down the street from my hotel. I invited him in, but he said he had to get on with his evening run. But as I opened the door to get out, he commanded in the old familiar voice, “Buddy, you wait!”

For a moment I thought my fly was open or something. “What’s wrong?”

“What you got there?”

I was bewildered. “That? You mean this bag? That’s a piece of sweet potato pie Bea fixed for me.”

“You ain’t going through the lobby of no big hotel carrying no brown paper bag.”

“Man, you crazy! Of course I’m going—Look, Bea fixed it for me—That’s my pie—”

Charley’s eyes were miserable. “Folks in that hotel don’t go through the lobby carrying no brown paper bags. That’s country. And you can’t neither. You somebody, Buddy. You got to be right. Now, gimme that bag.”

“I want that pie, Charley. I’ve got nothing to prove to anybody—”

I couldn’t believe it. But there was no point in arguing. Foolish as it seemed to me, it was important to him.

“You got to look right, Buddy. Can’t nobody look dignified carrying a brown paper bag.” So, finally, thinking how tasty it would have been and how seldom I got a chance to eat anything that good, I handed over my bag of sweet potato pie. If it was that important to him—

I tried not to show my irritation. “Okay, man—take care now.” I slammed the door harder than I had intended, walked rapidly to the hotel, and entered the brilliant, crowded lobby.

“That Charley!” I thought. Walking slower now, I crossed the carpeted lobby toward the elevator, still thinking of my lost snack. I had to admit that of all the herd of people who jostled each other in the lobby, not one was carrying a brown paper bag. Or anything but expensive attaché cases or slick packages from exclusive shops. I suppose we all operate according to the symbols that are meaningful to us, and to Charley a brown paper bag symbolizes the humble life he thought I had left. I was somebody.

I don’t know what made me glance back, but I did. And suddenly the tears and laughter, toil and love of a lifetime burst around me like fireworks in a night sky.

For there, following a few steps behind, came Charley, proudly carrying a brown paper bag full of sweet potato pie.