Sisterfeast and the Manna of Afro-Carolina

By Michelle Lanier with Kali Grosvenor

“Patrizia Cavalli’s Christmas Table” (2020), by Louis Fratino. Oil on canvas, 45 × 30 inches (114.3 × 76.2 cm). © Louis Fratino, courtesy of the artist; Ciaccia Levi, Paris; Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York. Private Collection, Paris

This story begins with an ending, two in fact. Kali Grosvenor and I did not meet until after the passing of the two women who make us kin. Cultural giants in different ways, her mother, Vertamae Smart-Grosvenor, and my grandmother, Anne Grace Caution, found each other and created a sisterhood that still feeds their progeny, like manna when we least expect it.

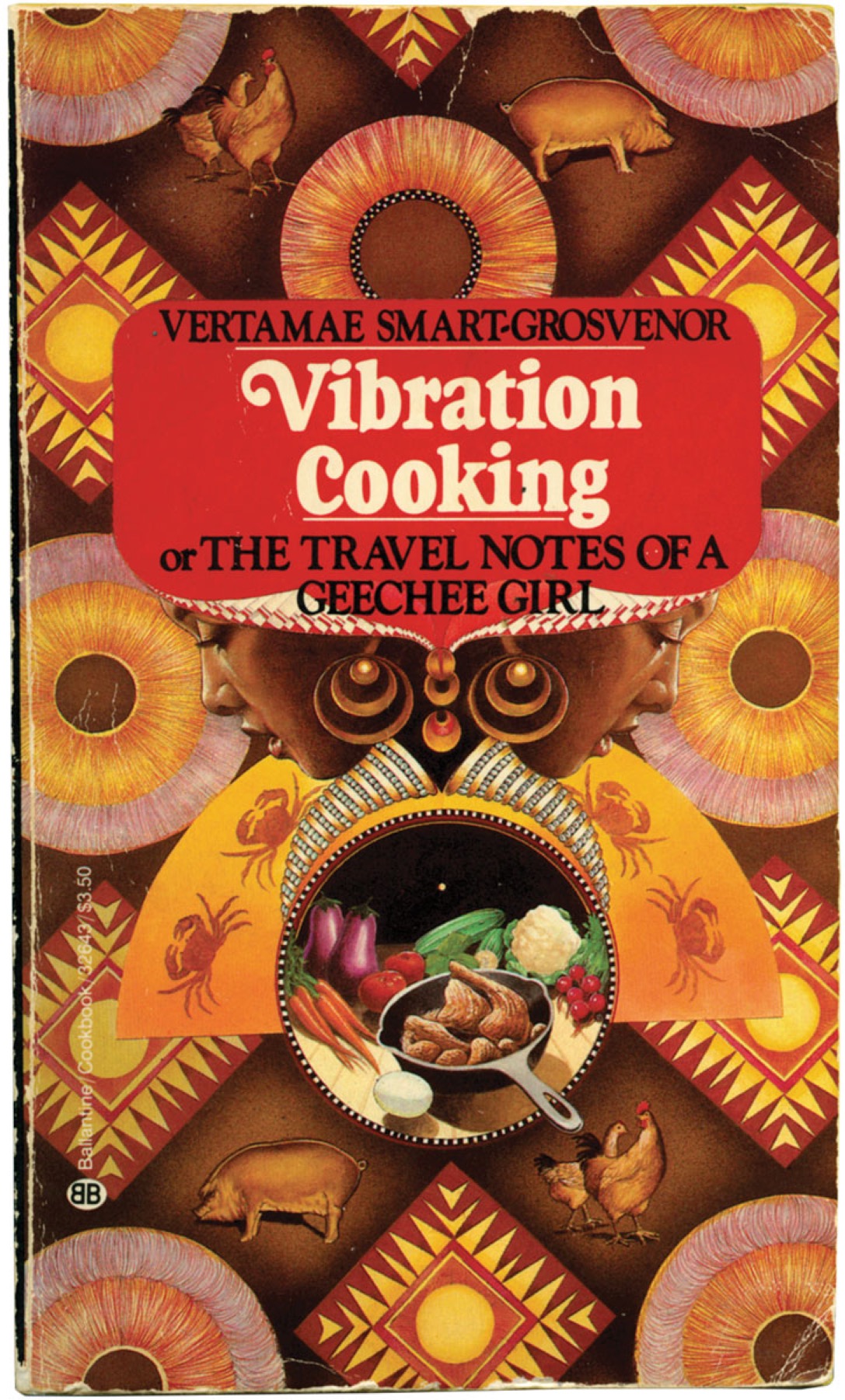

For the uninitiated, Vertamae Smart-Grosvenor was/is a culinary icon. Geechee Goddess of screen, hearth, and pen, raconteuse, wearer of rainbows, earth traveler, she documented the nuances of soul food in her iconic book Vibration Cooking, which is over fifty years old and still in print.

Anne Grace Caution, matriarch, welcomed the bold and the broken into her home, survived tragic family deaths and upheavals that were the spiritual equivalent to multiple great floods. She also adorned herself with gold like an elegant pirate, inspired the creation of commissions for the heritage and healing of her people, cussed when it was necessary and genuflected when it was not, birthed wisdom from her womb, including children and grandchildren who continue to be called “first Black person to (fill in the blank).”

Both were Afro-Carolina born. Both were carted to Up South, Philadelphia. Both left for Europe, just after crossing the threshold from girl to woman. For one, it was the call of adventure and the art world, for the other, the call of duty to the work of an Army wife. Both loved a good story, a good laugh, fabulous clothes, most wine, and, yes, good food. And when Verta came to visit with Anne Grace on Washington Street, in Columbia, South Carolina’s historically Black Waverly community, we granddaughters of Anne hovered as long as permitted, bathing in the magic of Verta’s adventures. She would recount teaching Oprah Winfrey to make biscuits as if she were angry, in preparation for a scene in Beloved, or saving the life of a young hot dog thief being threatened at gunpoint by a cashier at Katz’s Delicatessen in New York, or reenacting Angela Davis’s grand entrance, in a miniskirt no less, at the party Maya Angelou threw in honor of Toni Morrison’s Nobel Prize.

It wasn’t long before Anne’s granddaughters would be “invited” to leave. And now that I am grown, I know that this loving dismissal foreshadowed the real “sisterfeast,” with true soul food too rich for young hearts.

Perhaps it is the parade of death brought on by police brutality, the pandemic, and the health disparities that hit even the bougiest of Black families, but in 2020, the year of the Great Upheaval, I kept reaching out to Kali (our voices, then faces, meeting in virtual realms over the phone, then Zoom), and Kali kept answering, again and again, as if we were just mid-sentence, mid-story, mid-laugh, mid-meal. We remembered these women, our women, and saw they had been waiting all along.

SETTING THE TABLE

Though we are speaking by phone, I imagine a tablescape set with vibrant textiles from Vertamae’s travels and Anne Grace’s mid-century modern china. There is, on a sideboard or counter, a huge bouquet of Carolina garden flowers (azaleas, hydrangeas, crepe myrtle, camellia, dogwood, or daffodils, depending on the season).

Michelle Lanier: Kali, when did Aunt Vertamae pass away?

Kali Grosvenor: In September. September 3rd, 2016.

ML: My mom passed in September as well, but in 1985.

I remember finding out about your mother from my first cousin, Lanier, who was extremely close to Aunt Verta. I told her, “I would really like to reach out to Kali.” Even though my grandmother and your mother were quite close, and I had met your daughter, for some reason you and I had been like ships passing, only hearing of each other. Lanier sent me your phone number and I left a voicemail message saying something like this: “You do not have to return this message. This is Shelly. I am one of your mother’s nieces by love. I am a granddaughter of Anne Grace Richardson Caution. I’m just calling to let you know that we are holding this moment with you. We love you. Your mother was so loved. She brought so much into our lives, and we’re here if you ever need anything.”

KG: I wasn’t prepared for my mother to leave, so I was sort of in a cave, a hibernation, you know, immediately following her death. I started getting little “lights”—people calling, beautiful people—but I couldn’t speak to everybody. I called you back because my mother loved Anne Caution. I didn’t know the details of their sister-love, but I knew that Anne Caution’s granddaughter was out there calling in, and it touched me.

ML: I love that the name “Anne Caution” was like a clarion call. Like, “Wake up. These are your people reaching out for you, and these are people who it would be good for you to allow yourself to be embraced by,” even if it’s just over the phone. I feel the same way about your mom. If I hear the name “Vertamae Smart-Grosvenor,” if I see her image in a film even, I can’t help but call out. I don’t have a choice. Those who knew her understand the expectation that anyone she loved, anyone she embraced, better yell out her name after her death.

KG: I think that’s what spoke to me, too, about your grandmother’s name. When you were calling me, you also needed me to acknowledge your loss.

ML: We were in there together.

I can just hear my grandmother saying to your mother, “Oh shit, Verta! Enough of that. We’re gonna sit here and cry all night!”

They knew how to shift energy really quickly, maybe sometimes to our detriment, but they knew how to shift.

ALL THE SIDES

Greens Two Ways—one, sauteed collards and the other a blend of simmered turnips, collards, and mustards for the Pot Liquor “Tonic”

Michelle’s Sweet Potato Pone—roasted sweet potatoes whipped to a pillowy lightness, sweetened with brown sugar and golden raisins, topped with maple pecans and cinnamon

Fried Okra—garden-fresh okra batter-fried in seasoned cornmeal

Sauteed Garden-Fresh Yellow Squash (just for the ancestors)

Quick-pickled Garden-Fresh Sliced Cucumber & Tomato in Spiced, White Vinegar

Hoe Cake—stone-ground cornmeal and clabber or buttermilk mixed and fried thin in a seasoned cast-iron skillet

Rice—Carolina Gold rice cooked until tender (for Verta)

Pan-fried New Potatoes and Caramelized Onions (for Anne)

Salmon Cakes (Croquettes if you’re Fancy Anne’s Progeny)—breaded, fried, and served with buttered grits

ML: So, we’re honoring these women. We’re honoring this bond we’ve inherited from them. We’re honoring each other. If we were physically together, what would our feast be? I imagine it would be a lingering feast that would go on for quite a while. There’d be long talks into the night, like the ones I recall these chosen sisters having, that go on to three in the morning. One of us would say, “Oh, just stay the night!”

KG: So we’d have, I hope, hoe cakes or something with yellow cornmeal, right? Because that’s for all of us. And we have to have rice!

ML: Oh, we would definitely have rice. But, what’s so funny is we would have rice because of your mother, because my grandmother was very clear about her feelings about rice. She would say, “I eat potatoes. I don’t eat rice. I live in South Carolina, but I am from North Carolina”—the potato eating part. So there’s the two Carolinas, you know, I call it Afro-Carolina. We would have rice to honor your mother’s ancestral geography. Then we would have potatoes, and they would be fried with onions, for my grandmother. We’d have to have grits in the morning, for both of them.

KG: I just want to say something about the rice and potatoes. My mother must have loved your grandmother! My mother does not tolerate those people that try to put rice down. She does not! I don’t even know a person that ever got away with talking about “I’m from North Carolina . . .”

ML: Oh, Grandma would have never said that around Verta!

KG: I don’t know how your grandmother could have kept that a secret from my mother, because all my mother talks about is rice!

ML: And all Grandma talked about was potatoes! But where they met in the middle was with grits. Grits was their unity.

KG: And don’t get those instant grits.

ML: Yes. I messed up and did that once with Anne Grace.

So this next dish is an almost sacred act of commemorating Anne Grace. It’s salmon croquettes. I see it as a necessity food, a survival food sometimes prepared by women who had a comfort level with both luxury and austerity. We would take one large can of salmon and Grandma was very particular that you did not ever get the cheap salmon. It had to be the good salmon.

KG: Is it sockeye salmon?

ML: Yes. And she was very specific. She knew how many croquettes you should expect to get out of that can. It was eight croquettes; eight salmon patties came out of a can. She would also say, “And we don’t put breading inside the croquette. We don’t stretch the filling.” She would do salmon, one egg, one tablespoon of mayonnaise, diced onion, seasoned to taste, and breaded with Italian breadcrumbs. Now, after my exposure to West African cuisine from my Ghana people, I started adding fresh ground ginger. It feels like a part of the ritual to use a stone mortar and pestle. To just grind it is kind of sexy. I add the tiniest bit of Scotch bonnet. I also like to fry them in a mixture of olive oil and coconut oil. I still get about eight per can, like she showed me. We were raised to eat this as a breakfast food, with grits, but then as I got older I was like, they’re so good, you can eat them any time of day, hot or cold.

KG: I love salmon cakes. I’ve always loved them. I make my mother’s recipe, which I didn’t realize was one of my favorite foods until I went to college. I didn’t realize my mother knew how much I loved them until the morning I delivered my daughter. I delivered at 8 A.M., and she was there, at the hospital, at 9 A.M., with food. She brought me a plate of salmon cakes and grits. She said, “I knew you’d be hungry.”

Now I’m thinking of the recipes as representative of them. I don’t use mayonnaise or the breadcrumbs. I just use a little flour, very little flour. And I use lemon juice. [Michelle gasps in awe.] Fresh lemon juice and the egg, and then I make them into patties. But this discussion is really deep, because maybe I can change my recipe!

ML: Well, I’m definitely going to try the lemon, now!

KG: I think it’s kind of beautiful. It never occurred to me to add something to those salmon cakes. It’s like the recipe passed down, and it took me so long to learn how to make them. But no, based on this, I can add things and still be honoring the original taste. I’d love Scotch bonnet in it, because I drown them in hot sauce. I do want another kick.

ML: And of course, just a sliver, because you know how powerful that pepper is.

KG: Just a sliver, then wash your hands.

We need a lot more food, because we have to serve different dishes that mean things to them and to us. Right?

ML: Yes!

KG: Well, we have to have a lot of collard greens, or mustard greens and turnip greens. We have to have greens. We should have all the greens! We should mix them. I don’t think we need meat in them.

ML: My grandmother would throw a smoked turkey wing in there.

KG: That’s fine. My mom rarely made, and I rarely make, the ones in the pot. I make my greens in a cast-iron frying pan . . .

ML: And sauté! So we would have both. We’d have the sauteed greens, and we would have the pot greens for our pot liquor.

KG: When I make pot greens, I make them for the liquor, because maybe my daughter was sick or maybe I didn’t feel well. In that moment, the greens are secondary. Did you know about the power of pot liquor growing up?

ML: I did! But, I was not a fan of greens as a little girl. Though, I remember getting the flu my first year at Spelman. When I came home for Thanksgiving and went to visit Grandma’s house, she insisted that we all needed to get our immune systems strong. She made sure all of us grandchildren drank cups of collard green pot liquor. I now cherish pot liquor and I’m grateful that I have a daughter who loves collard greens.

KG: When my daughter was younger, if she was sick I would make that as her tea. She would say, “Mommy, you might need to make me some pot liquor, my throat is sore.” She actually knew it was medicinal.

We did say sweet potatoes, right?

ML: Yes! And to honor my grandmother’s love of sweet potatoes, especially around the holidays, I make a sweet potato pone, which is kind of like a pudding. You bake the sweet potatoes until they are super soft and you can add in pecans, raisins, walnuts, and golden raisins, and definitely brown sugar. And I can just take a bath in that.

KG: Oh wow! Well, we need some kind of pork. A garlicky pork roast.

ML: Your mom would probably have done that. Yes. And my grandma would have made lamb chops with asparagus and mint jelly.

KG: That’s good! That’s actually good on our table, in that section over there, with the mint jelly.

ML: Well, they’re so pretty, those jellies! They’re jewel-like.

KG: We need something fresh.

ML: We need a plate of sliced tomato. Garden-fresh, somebody’s-mama-just-dropped-them-off-fresh. And fresh cucumber, just sliced, with the salt and pepper on the tomato and then like salt, pepper, and white vinegar on the cucumber. Okay. And I think my grandma used to make yellow squash, too.

KG: Okay. My mom made a lot of squash. I didn’t really eat squash . . .

ML: I wasn’t into it. We’ll let them enjoy that.

KG: Just make it for them.

KEEPING THE MAIN THING THE MAIN THING

Verta’s Shrimp Perlou—a one-pot shrimp and sausage dish, with a spiced tomato base, and rice (of course)

Anne’s Fried Whiting—fish procured from Palmetto Seafood Co. on Gervais Street in Columbia, SC

Kali’s Puerto Rican–Style Pork Roast Pernil—the most garlicky pork roast you will ever taste

Lamb Chops and Mint Jelly—pan-fried in a hot skillet and seasoned to taste with homemade garden mint jelly

ML: I’m thinking now of the stories these women shared over food. My grandmother would just sit there, smiling and receiving the grandness of your mother’s stories with love. I’m realizing this is not a thing to take for granted. If you’ve experienced something grand, who can you share it with? Who’s going to receive it with love, not with impatience, not with jealousy, but with true love and delight. My grandmother delighted in your mother’s stories and she laid the table for those stories to be shared.

KG: That’s true. My mother had some stories. Because the most wonderful things happened to her, or the most wonderful people walked in. She attracted that! That’s a burden, too, when your life is a festival, and then everybody else is like, “Tone it down!” She can’t tone it down, it’s how she lives.

ML: My grandmother listened to others, too. Vietnam veterans would come to the house and say, “Miss Anne, may I clean your yard?” Or, “Miss Anne, I need a few dollars for some cigarettes.” She’d often welcome them in. I remember her preparing sandwiches for them. I remember some of the young women who were at Allen or Benedict—two nearby HBCUs—would sometimes stay at her house, until they could get themselves together. Someone could be dealing with something really heavy and Grandma would put a 45 on that record player and play James Brown, all kind of Motown songs, Deniece Williams, Sam Cooke. She created moments for enjoyment, like magic. She knew how to shift energy and that shifting reached into the heart. She never, ever shamed anyone for their journey.

KG: My mom had a lot of dinner parties, countless dinner parties! Anybody could be there! It could be the janitor that she met when she was at Doubleday, visiting. She could recognize who needed that kind of love, or that kind of attention. That’s what she had to do. All of that grandness, and that sort of royal feeling that they give out, they really were that. They saw it as their responsibility, not to fix people, but to provide. What I think both of our people had in common was that the kitchen is sort of the heart and soul. And you can run the whole world from the kitchen.

ML: I think that is what this is. This is a feast that continues to feed us for these journeys. Our world is in a very particular journey right now. As Black women, we’ve already known, through our own lived experiences, in our own bodies, and as daughters of Black women and granddaughters of Black women, and on and on and on, that we are magnificent. But the world seems to be just starting to understand that story a little bit right now, particularly with what’s happening in the political world. We have our Madam Vice President and all of these extraordinary Black women, like my Spelman Sister Stacey Abrams, and unknown thousands, all over the country, who have been a part of the liberation of the electoral process.

But there’s also a great deal of the world that is not comfortable with the brilliance, resilience, and magnificence of Black women. Your mother and my grandmother also knew that the world outside their kitchens was not the same as the world they created in those kitchens. We were getting food to certainly keep us healthy—the pot liquor to keep the colds away—but we were also getting a kind of spiritual food for the journey of being Black women in a world that doesn’t necessarily see us for, for all of us, a world that doesn’t see us as worthy to simply . . .

KG: . . . be here.

They taught us to always have that time, where you do have memories in the kitchen. It’s almost like we’re starting over with those concepts. We’re continuing to celebrate. We found each other so we could have an even larger celebration, an amplification of what was always around us. They’re superstars. And they were just, you know, making grits for us. They’re not gone and there’s still so much to talk about, to bring, to share with each other, and to pass on from what they taught us.

ML: These women survived a lot. They survived traumas. They survived heartbreaks. They held the broken hearts of their children and their loved ones and their friends. When we were invited to leave those spaces—so the grown-folk talk could commence—maybe I would turn to a bag of penny candy and they would share a bottle of wine, you know, for the same reason. It’s a kind of temporary soothing for broken things they worked to rise above. You’re right: They were superstars making grits. Even on my grandmother’s deathbed, I am told, she emphatically, with some of her final breath, demystified the essential nature of a Dutch oven—a heavy skillet with a lid—for my cousin Melissa.

KG: There’s this groundwork there. After people pass, and after they’re not with you anymore, you lean into your memories of them, and their teachings. You explore what your relationship was like, before they passed. Once you start doing that, you find all these secret messages and places of strength. I find a lot of strength in our salmon cake stories. They’re like photographs. I think the word is “grounding.”

When you and I started speaking over these past few years, we’re always talking about how your grandmother, my aunt, and my mother were so different. But it’s really fascinating how they put up a united front, at least to pass the love. We’re here celebrating these women, not only the ones we’ve named, but the ones that taught them, the ones who grounded them. I think I told you about my great-grandmother who used to travel with her own repurposed mayonnaise jar, that she used to carry her own water. So this is before bottled water. She also carried cloth, so that when she sat down on people’s furniture she always put a barrier between their furniture and her body. I don’t know where these things come from, but some of them I witnessed. Some of these things are sort of coded love letters, left behind, or love messages, left behind by these women who we love so much.

SWEET THINGS

Till We Meet Again Cake—a spiced fruit cake with a holy message

Corner Store Candy—cinnamon drops, melon-flavored lollipops, and grape chews

ML: I feel like there’s one thing we have to do before we close this out.

KG: Okay, what is it?

ML: I feel like your mother and my grandmother are tapping on my shoulder, saying, “You’ve left out something.” It’s something for this feast, and I’m like, “What is it?”

I know Grandma always kept butter pecan ice cream in that freezer . . .

KG: We don’t have any dessert. So, is that it? Okay. So, my mom can’t bake.

ML: And my grandma had stopped baking before I came along, so I don’t know.

KG: Okay, so we can do a peach cobbler. Verta can make peach cobbler or a pineapple upside down cake.

ML: Ooooh, I know what we have to talk about! The cake.

KG: “Till We Meet Again Cake!”

[sweet laughter]

My mom would go to South Carolina from Philly and spend summers. She was not like the people that migrated and turned their back on the South. So, when my mom used to go back, when she was a young girl, she would visit her maternal grandmother, that loved her so much, the one who saved her. She would be very, very sad when she had to go back to Philly. So her grandmother would make her this cake.

And actually, as I read it, it’s kind of emotional because that’s what we’re doing right here.

If she made the name of the cake “Till We Meet Again,” I guess we should name our salmon cakes.

ML: We can call the salmon croquettes “We Will Meet Again!”

KG: This is the problem, though! It’s like the potatoes and the rice. You guys call them “salmon croquettes” and we call them “salmon cakes.”

ML: Fancy!

KG: And that’s the thing! I just love it between us.

ML: I love it, too.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Till We Meet Again Cake

In Vertamae’s own words: “‘Till We Meet Again Cake’ is actually ‘Scripture Cake,’ very popular in the South. I named it ‘Till We Meet Again Cake’ because every time we would leave South Carolina, my Grandmother Sula would give me a hug and say ‘Alright now, you remember, every goodbye ain’t gone, every grin teeth ain’t a laugh, every shut eye ain’t sleep.’ Then, she would give me a juicy kiss, slip a few coins in one hand, and a few slices of cake wrapped in waxed paper in my other hand, give me another juicy kiss and say, ‘Be good sugar, till we meet again.’”

Ingredients:

1 cup butter | Judges 5:25

2 cups sugar | Jeremiah 6:20

6 eggs | Isaiah 10:14

1 cup water | Genesis 24:17

2 cups raisins | 1 Samuel 30:12

2 cups figs | 1 Samuel 30:12

1 cup chopped walnuts | Genesis 43:11

3 Tbsp. honey | Exodus 26:21

Spices to taste | 1 Kings 10:10

2 tsp. baking powder | 1 Corinthians 5:6

2 cups sifted flour | 1 Kings 4:2

Follow the advice in Proverbs 23:14. Blend and beat well, and bake slowly in a moderate oven (350 degrees Fahrenheit).