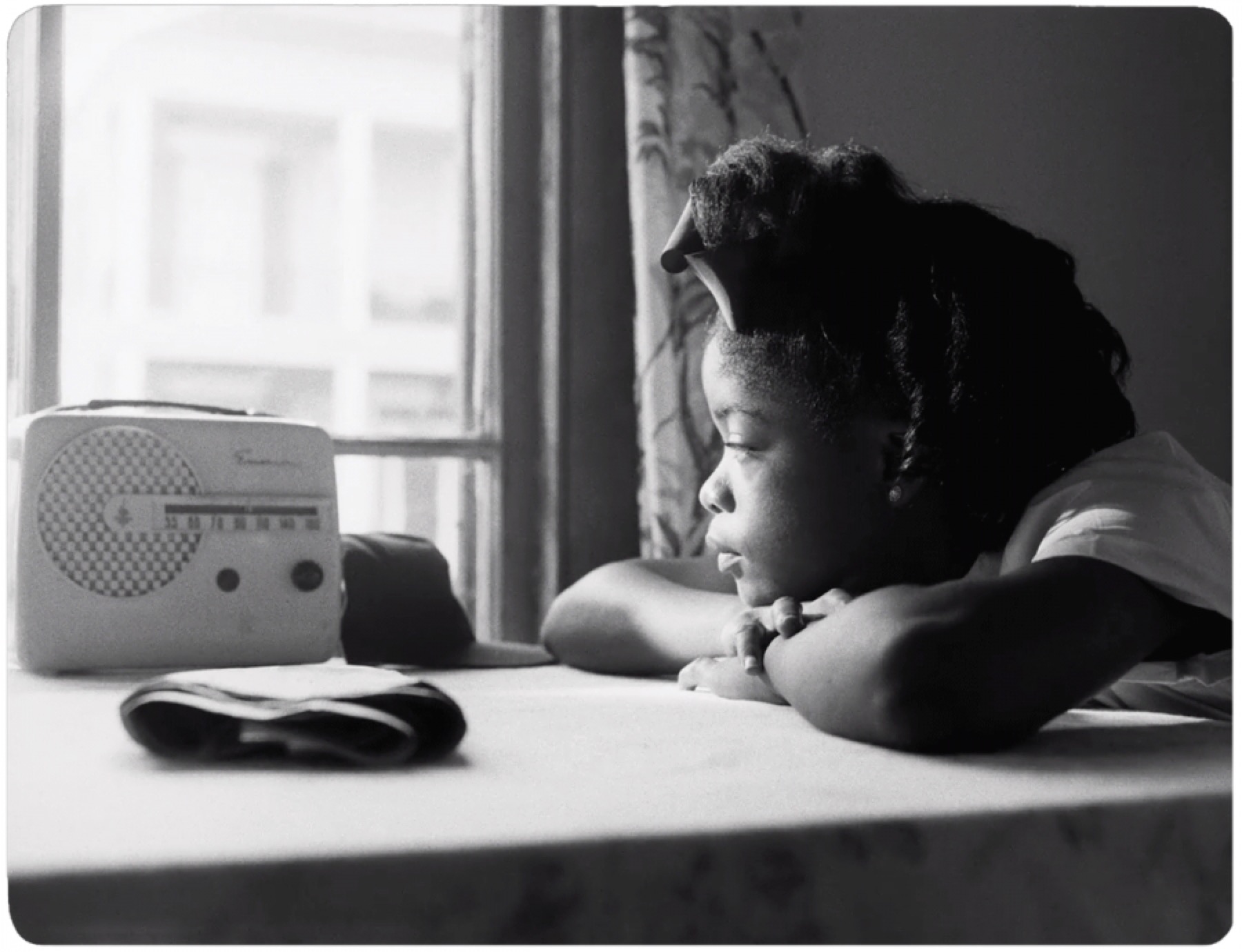

Still from America, by Garrett Bradley. Bradley’s exhibition Projects: Garrett Bradley is on view at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City from November 21, 2020–March 21, 2021

The Way They Strut

By Alice Randall

M

aps can tell lies. Let us consider the ways: How a Southern blues map that only includes spaces east of the Mississippi River, south of the Mason-Dixon Line, does not tell the whole story. How a Black music map that only sounds like the blues and what that genre birthed misses some things.

That kind of map keeps us from noticing that Louis Armstrong and Lil Hardin played on “Blue Yodel #9” when Jimmie Rodgers recorded it in California. That kind of map, focused on a country-soul triangle of Nashville, Memphis, and Muscle Shoals, keeps us anchored in a place where the white audience dominates and white economic power controls Black aesthetics.

But now is a time of reckoning. It is a time for reclaiming Black art aesthetics and acclaiming lost, erased, and overlooked Black artists, who daily and historically endured emotional, physical, and economic assaults while (ironically) sustaining others with their sound.

Every time I listen to Chicago-born LaVern Baker’s extraordinary 1958 album, LaVern Baker Sings Bessie Smith, I start thinking about Smith singing “Nashville Women’s Blues.” Soon I find myself nodding as Smith proclaims, “The way they strut it really ain’t no bluff.” Then quick as Joe Louis’s fist, I am thinking about how both Baker and her aunt and mentor, Memphis Minnie, moved to Detroit to make a home among, and music for, a powerful Black audience composed largely of Black factory folk, many of whom were, just like Joe Louis (who Minnie immortalized in “Joe Louis Strut”), straight up from Alabama.

After that listening, I start plotting new points on a new map: a country-soul five-pointed star. I start thinking about “up” South.

If I know you well and you ask me where I was born, I proudly declare Detroit, Alabama. The government identifies Michigan as my birth state. Michigan is printed on my birth certificate and on my passport. Michigan is my “government state.”

The term “government name” is used in certain circles to indicate that the name that is printed on your Social Security card and other state-issued documents may have no bearing on the lived experience of the reality of your life.

When I was playing on my grandmother’s lawn on a Detroit street called Hazelwood, an open-bed truck piled high with watermelons would roll down Hazelwood with little brown boys sitting atop the produce sing-song announcing they were selling “juicy fruit, juicy fruit,” a slice for a nickel or a dime, depending on how big the slice was.

When it was time for me to take an afternoon nap on a patchwork quilt at my grandmother’s, someone would put an album on the stereo to soothe me. My favorite toddler tune? Big Maybelle on the stereo talk-singing about “kicking in the barn.” And when I sang along it was in the round, soft, Black Alabama drawl I inherited from my family. Up South, even children knew Big Maybelle sang “Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On” before Jerry Lee Lewis.

My first taste of solid food was yellow cornbread crumbled into warm milk and baked in a skillet that had been toted north in a suitcase, a skillet slicked with bacon grease. My first swig of pop was Coca-Cola and if I wasn’t hungry for breakfast, Dear, my father’s Alabama-born mother, served me the breakfast of hardworking Black Up South champions. No, it wasn’t Wheaties; it was a swig of Coke and an aspirin.

My Detroit was a place where grandmothers called Dear and Ma’Dear cultivated rose gardens, and froze flower petals and fruit into the ice they floated in their sweet tea after digging little goldfish ponds to create a landscape that looked something like the land they left—because they had to leave, because the South, sweet as it could sometimes be, refused to stop oppressing them.

You come Up South to build a better South. You come Up South to celebrate a reality that is almost impossible to celebrate or often even see down South—that African and African-American aesthetics are the backbone of three great Southern arts: preaching, food, and music.

A better South, the Up South, insists that Black artistry and industry be recognized for their excellence, and that the measure of Black art be located in the pleasure of Black audience.

Nobody knew this better than LaVern Baker and no place provided a more significant Black audience than the Up South metropolis that was the Motor City.

Today, call me an author, call me a biographer, call me a country-soul cartographer, and then follow me to some new geographies. I’m talking Chicago. I’m talking Detroit. I’m talking as far as the Philippines. The best way to get the message right is to tell a story.

The works of early blueswomen inspired me to use my fifth novel, Black Bottom Saints, to shine light on notable Black women singers and songwriters who functioned as public intellectuals but were not recognized as public intellectuals: notably Ethel Waters, Eartha Kitt, Della Reese, and LaVern Baker.

Black Bottom Saints is written in the fictionalized voice of Ziggy Johnson, a real-life Detroit tastemaker, emcee, educator, and entertainment columnist for Detroit’s great Black newspaper the Michigan Chronicle. Please sit back and let Ziggy tell you a story about LaVern Baker, patron saint of: globe-trotters, the robbed, the resurrected, and seekers of resurrection.

THE SOUND OF HER

Excerpted from Black Bottom Saints

There are all kinds of theft. Sometimes petty theft can be pretty. And there are lazy little larcenies with killing sting. Sometimes it’s just calling a theft petty that bruises. And every different kind of theft leaves a different taste in the mouth. My dear friend, my sweetest girl, LaVern Baker knew so much about theft, the sound, the sight, the taste, the feel, the scent of theft, one day she stole herself. She left Detroit, left Motown, stole away to freedom, via a Far East Asia USO show.

Everybody knows about Josephine Baker, and I knew her too, but my La Baker was LaVern, who started off in show business, in my first business, as Little Miss Sharecropper. Lord have mercy, today! LaVern Baker started off as Little Miss Sharecropper and she won’t make it home from the South China Sea to say goodbye to me. But first and for a good long while singing from the stage of the Flame she was the toast of Detroit City when Detroit was Black Camelot.

LaVern Baker’s kiss, that is a girl kiss I will miss. When she started gigging, she was making three dollars a week. I lived to see my La Baker banking five hundred dollars a week. I lived to see her have children completely unrelated to her named for her. I lived to see Al Green manage her or come as close to managing LaVern as anyone could do. I lived to see her opening in New York at the Baby Grand Lounge. Al got that for her and he got her a spot on The Ed Sullivan Show in 1955, just before Christmas. November 20, 1955, was the date. The event was so important to me even the fog of illness doesn’t shroud that date, and that’s without keeping a TV Guide clipping. I see clearly those four dresses, gorgeous garments, her devoted friend Al Green had made for LaVern, just in case Sullivan put her in one more spot on the show than she was promised. Or Sullivan kept her around to play the next week. But Ed Sullivan never did right by LaVern the way he did by Della Reese. Our LaVern wore the hell out of those dresses even if she didn’t wear them all on network television. Even if you had to be in the smoky room to see her, to hear her, to dream, only dream, of touching and tasting her. LaVern, she didn’t give nothing away, often or easy, except her sound.

The sound of her. That’s where the trouble began and how, eventually, somewhere in the Far East, maybe Thailand, maybe Vietnam, maybe the Philippines, the trouble ends. She has a thrilling voice. Even at the beginning as Little Miss Sharecropper, it was a voice that froze and thrilled a room. I had a dream once (bet the number based on the dream, and the number hit) that featured LaVern picking cotton, a girl of ten or eleven, working in an Alabama field, and as she and the others around her worked, LaVern started to sing high and loud and everyone stopped picking cotton. And then they got beat for stopping and she got beat for singing. But LaVern kept singing and the other hands kept listening, swaying and crying, because LaVern’s voice was what we called then “true.” Those Negroes thought they were hearing one of God’s own bright and brown angels right in the middle of a hungry and dusty Alabama acre.

LaVern was troubled by the theft of her beauty. The sun had burned lines into her face, poverty had mangled her teeth and mottled her skin. I’ve seen her look into a mirror and say right out loud, “I got robbed.”

If she got robbed, she must have started off richer than rich. I tried to tell her many times she was so beautiful. But all she would believe was that her voice was beautiful and maybe sometimes she believed she was her voice. Oh, my dear girl, my Little Miss Sharecropper, my La Baker, my LaVern: You were so much more than your amazing, stolen voice. You are my favorite act of self-invention and self-reinvention. You are my North Star and you vanished when I needed you most—insisting, dear liar, that I didn’t need you at all. You are gone and I am dying and I am not sure that is a coincidence.

And I am glad you are gone. Glad you did what you needed you to do—not what someone else, even me, needed you to do. You became, in this last iteration, a flashing light of self-determination. I imagine one of my girls from the dancing school, one of my ballet babes, leading the kind of big and adventurous life that may one day lead across the world, to the South China Sea to kiss your cheek for me. When that kiss comes, LaVern, let it matter.

Let yourself remember sending me breathless postcards from Italy with directions to the postman, “D . . . liver . . . D.letter.D . . . sooner D better.” You made your preferences known. You gave instruction. It was not an act of spoilage, it was a generosity; the postman was included in your conversation.

Somewhere in Europe you picked up a title. You came back calling yourself Countess. In that phase of your manifestations, Al Green gave you $200 to buy a French poodle. Twelve hours later you were crying because the French poodle had run away. I thought he had been stolen. Nobody wanted to tell you. Better to think the pooch had run for her freedom. You got a new dog and named him Tweedle Lee Dee and I can remember you walking Tweedle Lee Dee down the John R. You never let that pooch off his leash even inside.

You didn’t cry over the large and obvious larcenies like in 1958 when Al Green died. God stole him from you. So many times, that man saved you from yourself. When you came back from Italy and you were playing the Apollo Theater and you hired a maid and a butler and I came to see you in your dressing room and had to explain to two strangers, the maid and the butler, who I was. No one could see you until they got past them. Then Al showed up and fired them. Al saved you from your pretensions.

And before that there was Georgia Gibbs. I hate Georgia Gibbs like I hate chitterlings that don’t get cleaned right. Georgia Gibbs singing LaVern’s notes and inflections are dirty chitterlings (something that should not exist, but does exist) that nauseate me.

Georgia Gibbs was a white woman who called herself a singer who copied note for note LaVern’s songs and made more money copying LaVern than LaVern made being LaVern. Georgia Gibbs stole LaVern’s sound. Stole her songs. Said they were her own. LaVern hated Georgia Gibbs almost as much as I did. But not as much. She was mad as hell at her. But she felt the compliment in the theft. If she had hated her as much as I did, she wouldn’t have been so agile in rebuffing her. Hate makes you stiff.

In 1957 LaVern took out a life insurance policy and named Georgia Gibbs the beneficiary. Then my dear lady wrote Georgia a letter and called her out by her first name. “Dear Georgia, insomuch as I will be flying over quite a stretch of blue water on my forthcoming Australia tour, I’m taking out an insurance policy and making you the beneficiary. If I die. Your career dies.” But my baby didn’t leave it at the humorous jab. She sued in court. She didn’t win but she sued for copyright infringement. That is my LaVern. Most singers have no idea of what intellectual property is, or that their phrasing and singing creates something that they own. LaVern Baker understood this.

LaVern, in her own way, tone and range, was a singer of the caliber of Ella Fitzgerald or Sarah Vaughan, my Sassy. But she didn’t get the acclaim they deserved and got. Two years ago, I was supposed to go to Sassy’s show. I wrote in my column that Baby Doll, Little Miss Office Worker, after a full day in the Executive Suite had managed to come home and fix ham hocks, string beans, and cornbread. After I had eaten my fill, while waiting to go out, I turned on The Big Valley to catch a little Barbara Stanwyck and I was off to slumberland. The point was, and no one got it, Stanwyck couldn’t keep me interested. If LaVern had been on the TV, I would have stayed awake.

After her Al Green died, she moved from the Orchid Room in Kansas City to the Flame Show Bar and then on to a homecoming of sorts at Roberts Lounge in Chicago—but it was a peripatetic and increasingly frustrating time in my LaVern’s life.

Like when Rudy Rutherford had his clarinet stolen and he wanted the mouthpiece back and didn’t get it. And in 1967, the year of the rebellion, I had a record player and speakers stolen from the school. I took it as a sign. I didn’t take it in my stride like LaVern had taken all the thefts she had experienced.

Until she didn’t. LaVern took off. I’m not sure how it was she had heard of the Philippines but that’s where she told me she was truly headed when she left on that USO show. She had worked abroad, Australia and Italy, but I think it was a Black serviceman who told her about the Philippines and the good life she could have there. It was some strange kind of do-over. She would have servants that she could actually afford and new clothes all the time because help, clothes, and food were cheap, cheap, cheap in the Philippines. In search of an easier street, she went globetrotting.

She quit us. Chasing a place where Georgia Gibbs couldn’t hear her. She quit us. She stopped recording. People in Detroit counted on LaVern to turn theft to beauty. And she quit us.

She returned to singing in a room full of uniforms like she had done when she was first starting out and the soldiers were dressed for or returning from World War II. She found and discovered belonging in a place where war always seemed right around the corner, and a revolution, and a world of spies, and Muslims and Christians, a place more different than many from Alabama would think possible. A place where she could forget Georgia Gibbs, forget sharing a bill with Little Miss Cornshucks, forget once being Little Miss Sharecropper.

When she first started singing she performed in overalls and a strawhat, in the clothes she had worn when she worked the fields, to honor those still working in the fields who she refused to forget.

I am forgetting. My name has been printed on thousands upon thousands of poster-bills. I have a single poster-bill in the apartment I share with Baby Doll. It advertises the Flame Show Bar. At the top is the word Flame in those bold burning letters and then the address 4264 John R at the corner of Canfield. The Flame was right down the street from the Gotham Hotel. The name Tamara Hayes in the biggest letters, then Andre D’Orsay and Nellie Hill and Leonard and Leonard. My name is in a box, Joe “Ziggy” Johnson, Comedy MC. Our Host was Morris Wasserman. Just above my name the letters that read: Little Miss Sharecropper Back from a Coast-to-Coast Tour. And there was a number to call for Reservations. Back in that day people came out in droves to come see us. Don’t let this get forgot.

We were an us, LaVern and I. We were an us. I wish I could see you one last time before I go upstairs. Slappy White says you’re dead. I know he’s lying. If you were dead, I would feel it in my bones, the way you are going to feel it when I die. We are an us. One of my girls, sometime not soon, will go out roving in the world, like I am teaching them to do, using you as an example, and she’s going to stumble on you, and hug your neck one last time for Ziggy. Kiss my child for me. Did I say that already? Let me say it again. Kiss my child for me.

Just look at LaVern Baker’s map. From Chicago to Kansas City, from New York to Australia, from Detroit to the Philippines, her country-soul cartography re-shapes her music’s center around the power and promise of the Black audience. Around the sustained and sustaining achievements of Black blueswomen who went globetrotting far beyond Dixie, taking their aesthetic of strut and witness with them.

A few years before I published my first novel, The Wind Done Gone, in 2001, Angela Davis published, in 1998, Blues Legacies and Black Feminism, a groundbreaking analysis of Ma Rainey, Bessie Smith, and Billie Holiday, in which she states, “the blues categorically refrains from relegating to the margins any person or behavior.”

And listening to Rainey, Smith, and Holiday after reading Davis, I heard that an aspect of feminist blues performance was a willingness to witness, a willingness to carry forward language, observations, and history that would be lost, stolen, distorted, if some Black woman did not make a place for it in her art.

Reading Angela Davis, I determined I would become, or die trying to become, a blues novelist. For me a significant part of that tradition is shining a light on blueswomen before me. I made a space for LaVern Baker in my art inspired by the space she made for Bessie Smith in her art.

The first song on LaVern Baker Sings Bessie Smith, “Gimme a Pigfoot,” is a complex celebration of female desire. Desire for country food, beer, and corn liquor. Desire to holler and to whisper coexist in this song, even as desire to disarm evolves into desire to demand and control (“check all your razors and your guns”). Competing desires get purred into an invitation to “shim-sham-shimmy” that announces both a desire to dance and the presence of a woman unashamed to want.

She is taking up space in the world and making space in the world by naming what she, body and spirit, wants.

LaVern hollers, growls, whispers, talks, mini-scats, and swings. LaVern’s voice, following the map of Bessie’s genius phrasings, is an instrument capable of complex and rapid rhythm change-ups, and the creation of true dulcet tones.

Bessie’s brilliant original is crowbar steel, calico, and burlap; LaVern’s version is silk and burlap. For me, the contrast without contradiction in LaVern’s performance is a magnificent vocal enactment of the Up South blues truth that life is bitter and sweet.

Syllable and sound LaVern builds on Bessie while paying tribute, copying little, honoring all, transforming the original, acknowledging the original, while matching Smith’s originality with her own. This is both profound call and response and profound calling out of the singer, Georgia Gibbs, who copied LaVern without acknowledging her and without adding anything to the cultural conversation. Before the battle was declared, LaVern Baker fired an important shot in cultural appropriation wars.

LaVern Baker Sings Bessie Smith should be studied as a significant text on the line between honoring and appropriation. And LaVern’s days in the Philippines should be acknowledged as proof of a global south.

In 1986, after moving from Motown to Music City (with stops in D.C. and at Harvard in between), I arrived in the Philippines as a young bride of a foreign service officer.

The touches of home I discovered so very far away from Up South or down South? Aretha Franklin’s raised-in-Detroit, recorded-in-Muscle-Shoals voice on albums and cassettes toted halfway ’round the world by every variety of American and other expatriates; and epic tales, told by a wider variety of folk, of nights listening to LaVern Baker, Memphis Minnie’s niece, sing jazz, blues, and her own early rock hits, and scat along to “Strutting with Some Barbecue” live in an officer’s club way up on Subic Bay.

I determined to make a pilgrimage. When I drove up to Subic, not sure if LaVern Baker would be performing or not, I was certain of this: if LaVern was strutting ’cross the stage, Little Miss Sharecropper, Memphis Minnie, Bessie Smith, and Lil Hardin were strutting, too. Looking for LaVern I found a larger world, where love is the strut and hate is the stumble.

The old map lost LaVern when she landed in the Pacific. Consider this an invitation to go exploring with a new map in hand.

A portion of this piece is excerpted from the book Black Bottom Saints: A Novel by Alice Randall. Copyright © 2020 by Alice Randall. Reprinted by permission of Amistad, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.