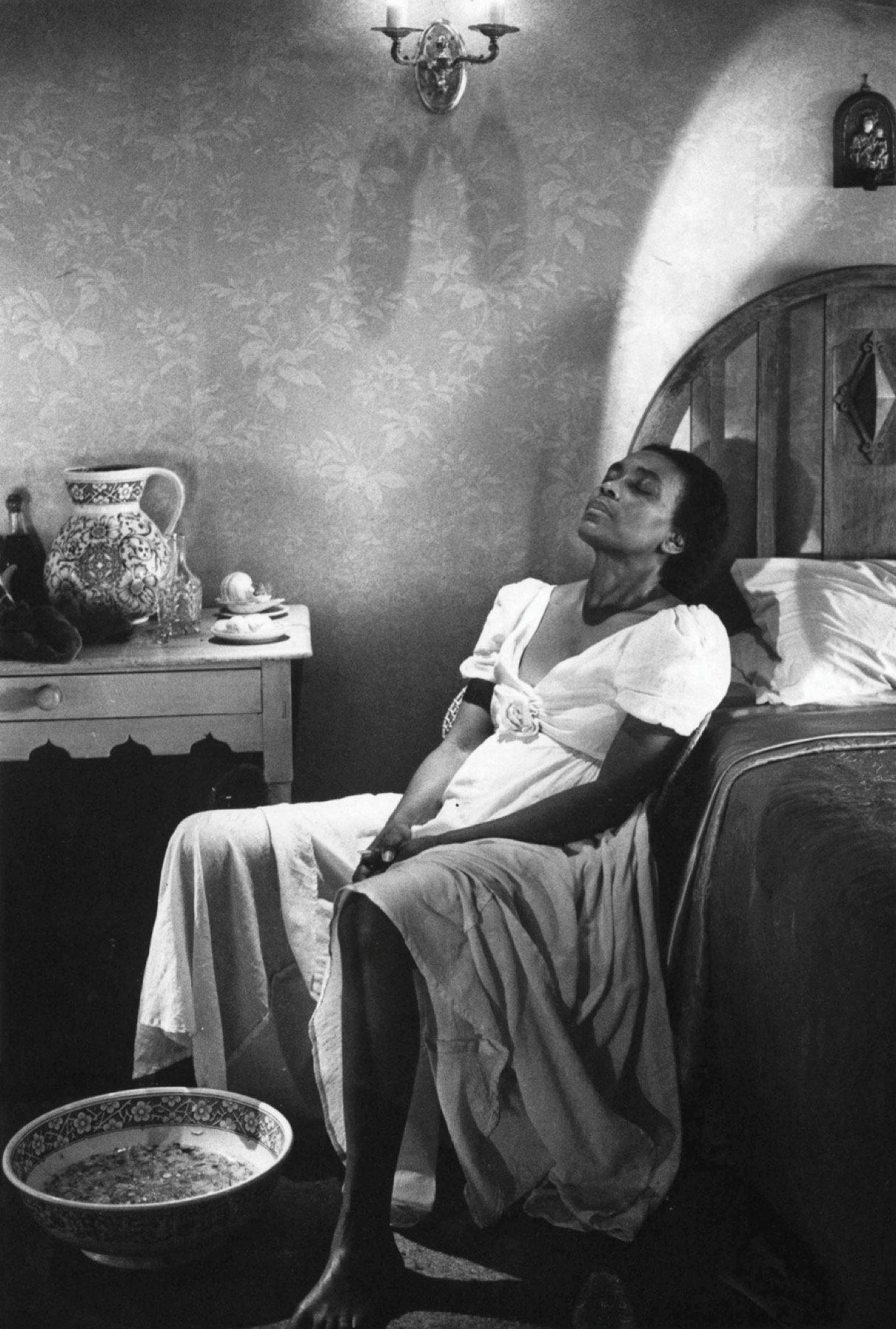

Corinne Skinner Carter as Ms T in Dreaming Rivers (1988), written and directed by Martina Attille for Sankofa Film & Video. Photo: Christine Parry. Courtesy Women Make Movies

Talibah Safiya: Oracle of Castalia

By Jamey Hatley

OUR FEMME OF PLAGUES

Memphis Minnie

W

hen I interview musician Talibah Safiya, Memphis and the world are months into a global pandemic and political protests against all manner of oppression. The world is different for us, but the world has been here before. Most certainly Memphis has.

When it is time to get ready for my interview, I try to work my usual rituals—take notes, research, listen to every piece of music, read every interview, clothe myself in the armor of preparation. But nothing comes from those old rituals, so I surrender. I do an old-fashioned Van Van floor wash, gather yellow paper and pencils and notecards, light yellow candles. And keep doing as I am led until my spirit is calm. I have been talking a lot about ancestral technologies in this time of pandemic, and “people” needing to heed them. I was people. People was me.

These are the things you don’t talk about in essays—the strange things, the magic things—but this is what this essay is about. Memphis, music, women, and magic. To find its shape I go to the river, drive around to the falling down or disappeared houses of greats, drink whiskey, cry over a heart that isn’t sure if it is breaking or becoming whole, pass my days as a daughter, a writer, a lover, a fighter, a woman making magic and wonder and wander the way forward. If such a thing as forward even exists now or ever has.

I think about our Memphis Minnie, born in Algiers, Louisiana, and how brave she was at thirteen to run straight toward her dreams and keep running toward them. Who wore her fine dresses and expensive jewelry, but would beat you down with whatever weapon available—her immense talent, a pistol, a razor, or even her guitar—if you dared to try her. I prepared the way I was moved, and when in a reversal, I tell Safiya “off the record” about my preparations, I’m not surprised to learn that she’d lit yellow candles on the day we speak on the phone.

The new ritual that is forming sends me to water. I sit and watch the Mississippi River from a spot called Martyr’s Park, after the devastation of the yellow fever epidemics in Memphis. I think about how this time is also being called an apocalypse. The root of apocalypse is to uncover, to reveal. I wonder if now is the time where this city, this country, will see itself true and do what is required to begin its repair with whatever tools required.

OUR FEMME OF HAINTS

Ruby Wilson

My friend Natalie Diaz and I were once talking about ghosts, and she told me that the word “haunt” comes from home. Aren’t all ghosts looking for a home that they can no longer access in the way they were used to? It made sense, in the way that a poet telling you something makes that thing both clearer and more mysterious. When I first met Talibah Safiya, I was a haint. After a decade gone to Louisiana, I suddenly found myself back in Memphis, helping to care for my “olders.” When I look back, the language of my return home is filled with death. A friend said I talked about my former home of New Orleans like a widow. When people asked how it felt to be home, I would laugh and say that I felt like a ghost, haunting myself. Indeed, at any moment I could encounter any of the selves that I had been over the entirety of my life, sometimes those selves layering quite unevenly over each other.

I had become a strange, wild thing away from home—even to myself. When I realized that much of my family was shocked that I had returned to care for my parents, that my leaving had been some sort of proof of my waywardness, I was wounded by their surprise. I was wandering, but not lost. I had only become strange through the gaze of others, others I thought knew me.

When I returned to Memphis from New Orleans, my best friend Caprice often indulged me on journeys where I searched for corners of my hometown that I hoped would remind me of the self I had been creating. One of these outings was a pop-up in a place that the city was now calling the Edge District in a building that I once knew as the Hattiloo Theatre, where I had seen an adaptation of Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye on its opening night. Now the place was emptied out and trying to become something new—and so was I. People my age mostly still call it “The Old Hattiloo.”

I met the pretty bull that day. Safiya is also a jeweler and maker, and the Pretty Bull is the name of her jewelry business. She was tall and beautiful and warm in that drafty building. The kind of person who emanates her own light.

She had been away in New York and was considering making her way back to Memphis, her home. There was so much light in her eyes about her return.

She told me that she was a singer and she had a show that night. I asked what time. Like 11 at night? I laughed, oh no. That is way too late. I bought brass bracelets and a clip-in septum ring—talismans that made me feel more like myself.

If you ask me what being a Black woman writer in Memphis feels like most days, I might direct you to the video of Johnnie Taylor singing “Last Two Dollars,” where I am subject, or backup, or audience. I am there in the room, but almost never at the center.

But every now and then, I’d direct you to a clip from the 1990 documentary All Day and All Night, where B. B. King, Mr. Rufus Thomas, and Miss Ruby Wilson, the Queen of Beale Street, sing King’s hit “The Thrill Is Gone.” “The Thrill Is Gone” is classic B. B. King. Wilson takes the lead on the song, and from her very first note the men know they best catch up. King himself shakes his head and says, “You think I’m singing behind that, you crazy.” On his own song. It is brilliant to watch.

I saw Miss Ruby at a performance at the Stax Museum right before she passed. She actually was stepping in for Bobby Rush, who could not make it. She was moving slower, but was still Miss Ruby—big hair, full makeup, nails, jewels, sparkle, and voice. She told stories in between songs, but that voice made a whole world. She filled the room and made it holy. She brought down all the ancestors who had played in that space. Little did we know that she would soon be among them. Miss Ruby brought me with her that night. After she passed, I pondered her catchphrase from an iconic commercial for a Memphis law firm: “Miss Ruby sings the blues so you don’t have to.” We were left to sing the blues for ourselves now.

It was in this same room at Stax where I first saw Talibah Safiya live. I knew then that a rare, rare thing was happening that I was blessed to witness. She was a whirlwind, a storm, a creatrix of worlds and herself. She was a haunting creating home. And she brought me with her.

A few months after Miss Ruby passed, my friend Marco Pavé asked me to record some interludes to his album Welcome to GRC LND. Once again, I was a ghost of myself—the twenty-something young woman who’d thought she might be a music executive one day. He was recording in a renovated studio in a building I had once sat in listening to other people try to make their dreams come true. After I recorded my meditations on Memphis and took off the headphones, I asked, “Did I sound like Ruby Wilson to y’all?” The people on the other side of the booth confirmed what I had heard. Like duende, Miss Ruby had crawled up through the soles of my feet. I had been carrying her along with me all the time.

THE CANDY LADY

Valerie June

In Black neighborhoods in Memphis, the Candy Lady is a tradition. In communities where the ice cream truck might not roll, if you can scrape up enough money, the Candy Lady is sure to oblige you. Chips, candy, pickles, and the like bought in bulk, but also sometimes food from the kitchen stove or a line of crockpots. Nachos, hotdogs, or freezecups where their brilliant color is the name of the flavor. Sometimes there is a table set up across the inside of the door to make a counter, dividing commerce from homespace. The table is a barrier to the kids (even the Candy Lady’s own) running back and forth through the streets, so only so much sweetness can be grabbed at once. Only now do I know the loneliness that could exist on the other side of that door. As children run into the neighborhoods drunk on sugar and salt, after the door is closed against the dark, the Candy Lady is counting her coins to see if the money will cover the gap of some bill or another. To find some way to sweetness for herself and her family.

When Safiya tells me that Valerie June is a big influence, this doesn’t surprise me. I remember that when I could not build a bridge in my mind to what a Black artist could be, there was this woman so much younger than me who seemed to be figuring it out. She worked in a local herb shop and sang at coffee shop open mics. I’m not sure if I had even started to write a word of my own yet, but June’s voice was full of country candy sweetness, the kind where you know that there is more underneath. That’s Valerie June.

The first songs that I listened to by Talibah Safiya had this soft, sweet, plaintive quality. There is something else underneath if you listen a bit closer: a little loneliness. The knowledge that this sweetness is fleeting. Even though these first songs that I listened to maybe didn’t sound like the blues (one streaming platform calls the tunes Millennial Jazz), the blues was certainly riding under the skirt of that sweetness. In this time of pandemic, I’m especially interested in the various ways that people seem to be feeling their loneliness or running from it. I wonder if that is something that I am projecting onto Safiya’s Memphis, her music:

Loneliness. It’s something that I have sat with a lot whether I was by myself or with other people.

And it has definitely inspired the creation of my music, so much so that I was resistant to allow myself to not feel lonely because I was concerned that I wouldn’t be able to create from a space of truth without it.

It has been a driving force into a connection with my truest self. Because then you can tend to your wounds, you know? And feel less alone.

I feel that’s where the music has come from at different times. But it’s crazy that I don’t feel as lonely now.

The loneliest I’ve ever felt was leaving New York and coming back home to my ancestral turf and having family close. It challenged my delusion of loneliness because I was still feeling it being close to my family. Seeing myself as lonely while in community challenged my relation to the concept.

We talk about the ancestors guiding us, [using] incense, burning certain candles or making coffee or leaving honey or pouring a shot of whiskey out. That directly conflicts with loneliness. If you believe, you can’t really believe in both at the same time fully. One concept challenges the other. Right now, I’m not feeling that lonely because of the listening and feeling.

The greater communication that’s happening that’s not just people that I see, touch on the daily, but the idea of communicating with something, with some forces you can’t see. It’s so comforting for me right now.

THE LADY SHARK

Aretha Franklin

One of the enduring, swaggering archetypes of Memphis is that of the pimp. Memphis is a city of many separate selves, so some of its citizens may be surprised at the varied history of the pimp mythology. Of my era, the acronym M.E.M.P.H.I.S. is a kind of shibboleth of time, race, and class. If I hear “Making Easy Money,” I expect it to end with “Pimping Hoes In Style.” The era of the pimp was probably most notably depicted in the 2005 film Hustle and Flow, written and directed by Craig Brewer and starring Terrence Howard and Taraji P. Henson. The song “It’s Hard Out Here for a Pimp,” by Memphis rap legends Three 6 Mafia, won the Academy Award for Best Original Song. But this swaggering pimp history goes further back than that. While in school I was taught that Robert Church Sr. was the South’s first Black millionaire. He helped fund the work of journalist Ida B. Wells and composer W. C. Handy. According to Beale Street Dynasty author Preston Lauterbach, “Church became the wealthiest black man in the South due in large part to his whorehouses that employed white women.” The source of his money may have been hidden from view in the textbook version that I learned, but his power certainly was not.

In Memphis, “pimp,” though not completely divorced from its original meaning, definitely has a colloquial meaning of a businessman, with ostentation, grace, and almost mystical powers of protection. For the most part, though, pimp equals male. Many of Safiya’s songs take this image of the swaggering pimp and turn it on its head. In her song “No. 50,” the female main character of the Pimp does battle with an archetypal “Lady Shark” in a black Caddy who has given the Pimp’s lover a potion that will subdue her and keep her off her goal of getting money.

In the first line of “No. 50” (the name of the debilitating potion), the character croons, “I keep my feelings in a jar, latent from the rest of y’all, ’cause I’m a pimp.” The jar spell is a common one in the practice of hoodoo, one that can be used for any number of purposes, but noted for its ability to use common ingredients and hide in plain sight. A jar spell to sweeten a situation could make use of honey or sugar. A jar for strife would perhaps contain vinegar or ammonia, rusty nails or the like. The Pimp has likely shut her feelings in a jar full of protective elements. The struggle of the Lady Shark and the Pimp is one for power. The male lover is the heartsick one, seeking the help of the powerful Lady Shark with the means to control his powerful, indifferent lover.

It’s Aretha Franklin both demanding her payment in cash and taking that purse full of cash onto the stage with her and throwing down her fur coat. And the Aretha that takes Otis Redding’s hit “Respect” and makes it hers. At the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967, Redding introduced “Respect” this way: “This is another one of mine. A song we like to do for everybody, love crowd. This love song is a song that a girl took away from me. Good friend of mine [exhausted laugh]. This girl, she just took this song, but I’m still gonna do it anyway.” Redding’s version is a plea of a man to his woman, even though he calls her a little girl in the song. He gives the usual male offerings of money and flattery in exchange for respect when he gets home.

The Franklin of our current imagination is “The Queen of Soul,” but when she recorded her version in 1967, she was only twenty-five years old. While well known in gospel, and touring regularly, she had yet to gain commercial success with her secular recordings. Franklin’s new arrangement flipped the gender roles, added interplay with the background singers, and spelled out R-E-S-P-E-C-T. This expanded the territory of the song. It was a remaking, a dismantling; she transformed a love song into a protest song, and put the world on notice. An anthem ripe for the struggle for women’s and civil rights.

OUR FEMME OF THE BIG WATERS

Lil Hardin Armstrong

Every Fourth of July, my parents and I would listen to the Sunset Symphony on television, mainly to hear James Hyter sing “Old Man River.” We would wait until the very end to hear Mr. Hyter’s powerful voice ring out among a mostly white symphony against the background of fireworks. I still remember being confused as to who was the Old Man River. It certainly couldn’t be the Mississippi River, but so much of the language of this city is gendered male. Both the “Father” and “King” of the blues made their marks in Memphis, the jookin’ dance culture, Memphis rap, the grit and grind motto all present mostly male. Also: “mane,” the most Memphis greeting, description, insult, compliment is undeniably male. This directly contradicts the feelings that I have about water. Perhaps my ideas about water were formed by the Mother Board of a Mississippi church that was founded in 1867, merely a few years after the end of enslavement. When those women sang a hymn of the salvation and saving grace of water, the trials and tribulations of water, their voices became water for me.

Talibah Safiya’s music is full of water. Of the Mississippi River, she says, “The river is my home. I find a nook where I can get close, and I sit and I breathe and I leave new.”

In Safiya’s song “Like Water,” the character asks if a partner only loves her because her insecurities make him feel powerful. Even though the intelligence of her body screams for her to leave, his charms make her reconsider.

I want to liquify and let you drink me up. Like water, like Kool-Aid, like soda, like whiskey, like white wine . . .

In “Healing Creek” the main character, done with making another the center of her world and worth, sets off to drink from the “Healing Creek.” In “Imagine That,” the singer asks, “Would you believe your paradise looked like the bottom of the ocean?” Water shifts through all of its forms—you can heal or drown or perhaps learn to breathe underwater.

Lil Hardin, another one of Safiya’s favorites, reminds me of water. Born in Memphis in 1898 to a very religious mother who wanted desperately to keep her from ruin in raunchy Memphis, she became an outstanding composer, pianist, and bandleader, even though she is mainly known as the wife of Louis Armstrong. Hardin was always making and remaking herself, as well as her husband’s look, music, and career. I was late to learn of Lil Hardin and her immense talent and influence in a male-dominated world.

Hardin’s polished, refined swing jazz style clashed with Armstrong’s big, country charm, as many have noted. Although she was one of the early women jazz composers, at one point she put music to the side and trained as a tailor, making a tuxedo for her famous ex-husband as her graduation project. She returned to music, however, on many projects, including work as accompanist for another Memphis legend, Alberta Hunter. In her essay “The Site of Memory,” Toni Morrison said, “All water has a perfect memory, and is forever trying to get back to where it was.” At her end, Hardin was like water. She collapsed at her piano during a tribute to Armstrong, a month after his death. She passed in the ambulance on the way to the hospital.

THE LANDLADY

Koko Taylor

Segregation required all manner of business adjustments. There were guides such as the Green Book and local directories to let Negroes know where it was safe for them to travel. Also, because Blacks were not allowed to try on clothes or makeup, mail order was important for daily living. These realities intersect at Memphis’s Eureka Hotel, called both “The South’s Oldest and Best Colored Hotel” and “The Hotel of the Dead.” The Eureka Hotel was a block down from the more famous Lorraine Motel, where Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in 1968.

My short film, Always Open, the Eureka Hotel (where Safiya makes a cameo as one of the shapeshifting Landladies), opens and closes with Safiya’s music. Only a scheduling conflict kept her from being one of the stars. In Memphis, seemingly incompatible things keep close company, such as the secular and sacred. The Lorraine Motel was the choice of politicians and preachers. The Eureka was the place for musicians and people looking for a little more colorful time in Memphis. When I ask about Safiya’s early days in music, she mentions the same powerful forces colliding to shape her style.

“The truth of it is that I grew up in a very Christian city of Memphis not a Christian. When I went to church, the thing that grasped me was always music. I have always felt spiritually connected to and moved by music, and because we didn’t have a place to go to for me to express myself in that way, I knew that music was the way to express that fullness in me spiritually,” says Safiya.

I didn’t really think that it was possible because I hadn’t seen any examples of that type of lifestyle. I went to school for theater because I knew I wanted to sing on stage. But this isn’t what I wanted to do, for real. I wanted to write and I wanted to sing and I knew it. I said, I’m going to read as many books as I can and I’m going to listen to music all the time until I feel like I’m a good songwriter. You know, it’s been a practice. I said to myself, I just want to be a part of this incredible tool for connection. This is my shit.

Part of the Memphis sound is exactly that collision. In my imagination, all of the upright-presenting “good Negroes” who might stay at the Lorraine Motel would make their way up Mulberry Street to the Eureka and have what Shelby County’s own Koko Taylor would call a “Wang Dang Doodle.” This is another instance where a remake has become the definitive version. Although originally written by Willie Dixon and performed by the legendary Howlin’ Wolf, “Wang Dang Doodle” is all Koko Taylor to me. The song itself is a litany of characters invited to the function.

All art takes practice. Singing, composing, playing, magic. Making all types of magic is work. And sometimes the most important work is to pitch a wang dang doodle all night long.

THE ORACLE OF CASTALIA

Safiya’s great-grandfather bought a house in the South Memphis neighborhood of Castalia in the ’50s. Her father was raised in this house. Safiya and her brother were raised in this house. Her brother is raising his family in the same house. Safiya and her partner live about five houses down.

“I walk the streets of my ancestors daily,” she says.

“So how does that kind of spiritual connection, do you think, influence your work?” I ask.

“I think it’s always been there. I think it’s always been what even allows me to connect. I have this really deep desire to be respectful to music almost like it’s a deity to the point where I have had difficulty with acknowledging my desire to be compensated for what I invoke in music. It’s felt like the focus was to show my respect for the art itself, show my respect for my life through the art, and find my confidence and strength through situations that might have temporarily caused me to doubt the truth of who I am. I would use it as a means to reconnect, right?” she says.

“Right,” I say.

“Almost like prayer or something,” says Safiya.

Exactly like that.

Exactly like that.

I realize when she says this that when my father made the small migration from Mississippi to Memphis, he and his siblings lived in Castalia, too. I have always loved the name Castalia. With a Memphis accent it is even more beautiful. Stretched out on a South Memphis tongue it sounds like cast-tell-ya. If that’s not a spell, I don’t know what is.

I realize as I started to think about speaking with Safiya, I am trying to make a map. Like the haint I was when I first met her, I am still trying to find my way to a home in my hometown.

Still on the phone with Safiya, I decide to look it up: Castalia. Those of you who know your Greeks were ahead of me from the beginning, but Castalia was the water nymph daughter of Achelous who occupied a spring at Delphi. In some tales the water is a gift, in some she turns herself into a spring to escape the advances of some lusty god. Castalia’s gift was the ability to inspire poetry in those who drank from her or could get still enough to listen to her waters.

After I read Safiya the description, we both sit in silence.

“Wow,” she says.

“Wow,” I reply.

A few days after our interview, Safiya sends me these communal meditations that seem to read into my soul. My life has somehow devolved into a kind of cheat sheet for the themes she explores in her music. The universe is pretty literal these days. The last one she sends is named for that ancestral street in Castalia where she lives.

Baby I don’t want to feel right now, or do you want to know the real right now . . .

I have been praying and meditating on healing for what feels like my entire life. Working on it, because our lives should be our best art. But in this moment, as I struggle to figure out what and how to write about Talibah Safiya’s art, and love, and magic, I run right into the place I want to avoid. A writing professor once told our class that the opening of any piece of writing should be like a bonsai tree. A miniature of the piece in full. I start with Our Femme of Plagues because I know that this is a big enough, worthy enough grief to carry. Memphis Minnie and Safiya make Memphis theirs in a way that continues to elude me. This is an undeniably worthy start.

What Safiya’s music and the music of all of these Memphis women uncover are the parts of me that I want to write out of the story—my sad parts, my fickle parts, my angry parts, my bitter parts, my heart that doesn’t know why it keeps trying to love ghosts, the part of me that isn’t quite sure that I am a worthy place to start. Unwittingly, the music of Safiya and all of these women wrapped my rooms in mirrors. Started my own personal apocalypse, a revealing. If I listen to the ancestral technology that is music, especially all of the Black women mentioned here, I would know that a single heart, even mine, is an undeniably worthy place to start.

You said you wanted heal-ing . . . Then, don’t avoid this feel-ing . . .

It is impossible to avoid now. I am undone. I sit with the Oracle of Castalia. I listen to her many waters and drink from her spring.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.