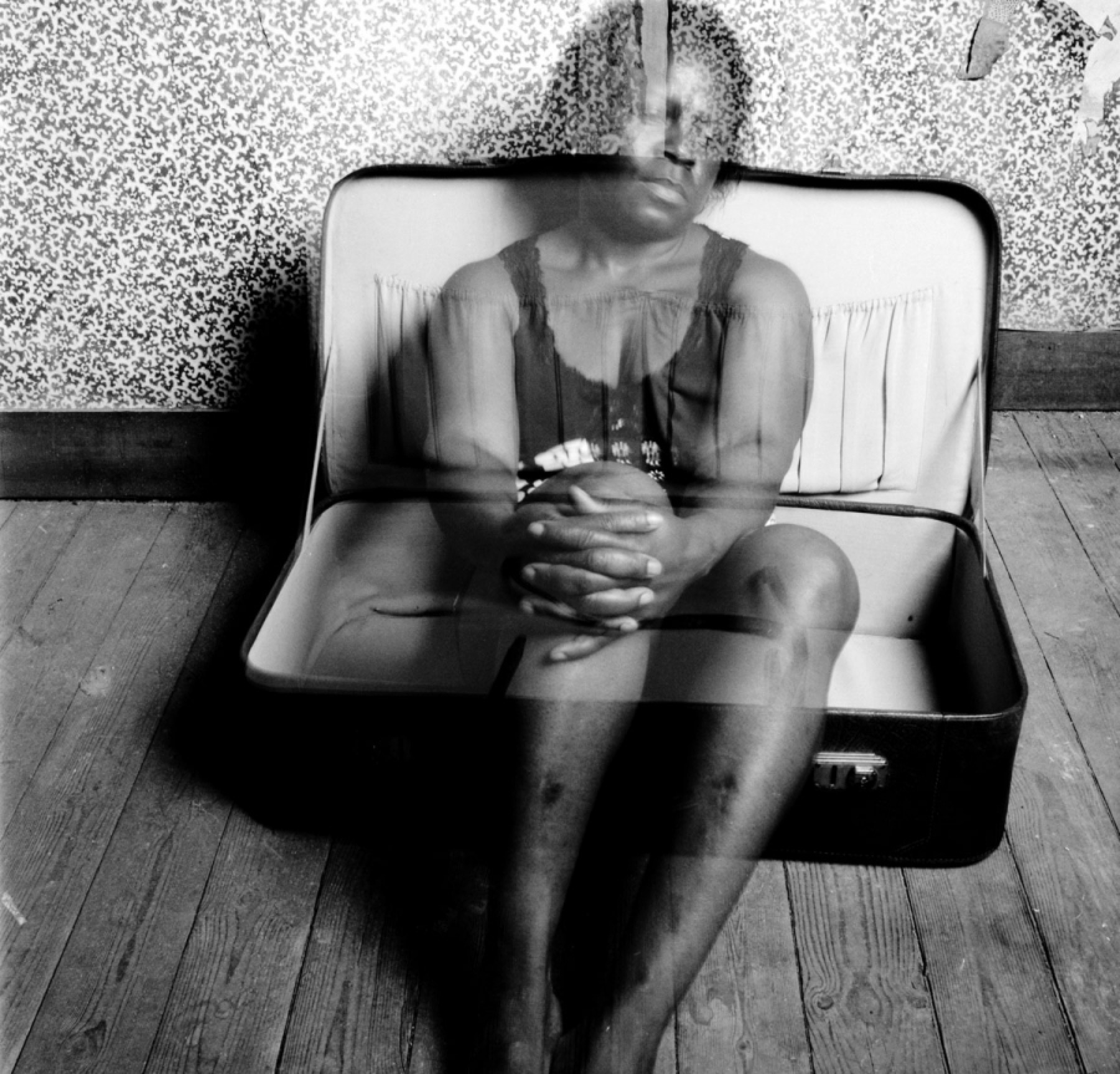

Photograph by Hélène Amouzou, from Fotofest Houston’s exhibition catalog, African Cosmologies: Photography, Time, and the Other, co-published with Schilt

The Visitor

By André Gallant

It began with a bus trip. Then a car ride. Long stretches logged by foot couldn’t be avoided. Nor could dark nights spent in makeshift dwellings, or storms muddying the dirty roads that lay ahead. Still, the migration found a slow rhythm: progress made by motorized transport followed by lengthy periods of inaction. Nothing slowed movement more than border crossings.

Affo had worked as a tiler—un carreleur—in Lomé, Togo, supporting a family who lived outside of the capital city, in a village where jobs were scarce. When a man with police connections tried to compel him to work for free, he balked, and the man threatened violence or jail. He couldn’t return to his wife and two sons unable to provide. At home, he’d be just another hungry mouth. So, Affo left. Opportunity lay abroad.

In 2013, he arrived in Brazil among a pool of laborers attracted to the country to build infrastructure for the World Cup. He constructed buildings in São Paulo and enjoyed the freedom of being unknown in a new place. In photos from this time, he poses with his arms around friends, on grand stone staircases, or with a hand grasping the door handle of a waxed car. He’s well dressed and smiling, a man seizing the moment.

When the matches ended, the jobs disappeared and Affo was again forced to choose between bad options: return home to limited prospects or risk his fortunes in yet another country. He heard rumors of a route into the United States. Everybody knew someone who’d left for the north, so the path didn’t seem so hazardous. Mostly on foot, he traversed the Darién Gap, a sixty-mile density of rough rainforest terrain between Colombia and Panama. Mountains and thick jungle narrow the passage. Rivers interrupt the monotony but present the most dangerous hurdle.

I tried to imagine his passage: everything he owned in a bag held high above his head as he descended into water that reached his chin. Dead bodies floating by, bumping him. Fear blacking out his eyesight, until he made it across, dragging his own body onto the northern bank, a feat only explained by heavenly grace, confirmation that his quest was righteous. Until he reached the U.S. border.

In 2016, three years after he left Togo, Affo joined thousands of migrants waiting in line in Tijuana. They lived in parks, or slept in the streets, their days spent in search of cheap or free food, preparing to plead their case. Like Affo, they all planned to ask for asylum. As he waited for his appearance before federal agents, he watched as other migrants hired coyotes to sneak them into the U.S. across the perilous desert. But Affo didn’t want to get busted and barred for life, or, worse, die from exhaustion. He wanted to do it the right way and ask permission.

When it was finally his turn to meet with border guards, Affo completed an asylum application, claiming that returning to his home country would result in his death. Afterward, he was placed in a cinderblock room and given a mylar blanket. He slept there for a few days before boarding a bus and then an airplane. Though the journey had been difficult, each step increased his hope; he was progressing toward a happy ending in the U.S.—he could feel it. Another bus met him after the plane trip, then a ride deep into a pine plantation where the bus came to a stop: a large parking lot, a beige building, empty transport vehicles parked at the ready. Barbed wire and concrete, patrolling guards.

Affo had arrived in Lumpkin, the seat of Stewart County in Georgia, and had been brought to what looked like a windowless high school. That year, Affo was one of more than 5,000 African migrants who attempted to cross into the United States at our southern border. Most were turned away. Dozens were transferred here, to Stewart Detention Center, home to its own immigration court. The court offers favorable verdicts for immigrants in less than two percent of cases. Affo couldn’t know it at the time, but the odds were not in his favor.

Stewart County is former cotton country, converted in the twentieth century to managed pine stands. In the process, people deserted the area, which wasn’t very populated to begin with. The county’s managed forests, comprising the vast majority of its acreage, teemed with deer and vultures. A dearth of taxpayers meant Stewart County’s roads and schools deteriorated. The Stewart County Courthouse—built in a Classical Revival style—anchors the downtown square. Near-empty storefronts surround it: a scuttled library where dusty titles still live; a store called Christian Gun Sales, which sells goods made in China; antique stores; and a patinated museum dedicated to soda fountains of yesteryear. Nearby, historic houses are abandoned, with collapsed roofs and slanted foundations.

The county was long primed as a perfect location for a private prison conglomerate such as CoreCivic, which operates fortress-like detention facilities in unpopulated areas where jobs are in high demand and critical scrutiny is unlikely. The Stewart Detention Center, which opened in 2006, was a tax boon and job creator.

Some men confined at Stewart come from Europe, Asia, and Africa, though the majority are from Mexico and Central America. Most of the people incarcerated there crossed the U.S.-Mexico border without papers years earlier, or overstayed visas. They had established deep roots and good lives in the U.S. For multitudes of reasons, their luck had run out. They’d soon be sent back to countries they barely knew, if at all, to communities that couldn’t care for them, or might wish them harm. Asylum seekers like Affo were fewer.

I learned about Stewart about a decade ago, when the state-wide fight for immigrant rights was ignited by a new round of bills brought before the Georgia legislature. I wrote op-eds in my local paper in Athens denouncing the laws, which sought to further criminalize undocumented workers, and marched in front of the state capitol with thousands of others. The comrades I made back then told horror stories about a prison in southwest Georgia. Proliferating reports produced by nonprofits detailed poor conditions inside: maggots in the food, ibuprofen as blanket treatment for every ailment, suicides, deaths. I came to understand Stewart as the place to which undocumented people from my community—people I worked with on jobsites, and parents of children in local schools—disappeared to as a result of immigration violations; the prison a purgatory before their eventual deportation.

I also began to hear about a modest house down the road from Stewart: a radical ministry called El Refugio, which offers temporary sanctuary to families visiting loved ones in the facility. El Refugio, which welcomes overnight guests with made beds and a fridge and deep freeze stuffed with casseroles and soups, practices an intimate activism, its political action rooted in calm, not crisis.

Volunteers run a pen pal program for detainees and facilitate a program called visitation. Visitation attempts to break the solitude that Stewart enforces on detainees by sending friendly faces in to speak with them. Interlocutors are paired by language capability: Francophones with Francophones; Spanish speakers with Spanish speakers. Visitors make small talk, but they can also assess conditions in the prison, collecting information about inadequate medical treatment or lack of food that might prompt human rights abuse inquiries. Visitation is a small but essential step in a massive human rights campaign, but the visits also break up long stretches of solitude—a small kindness for weary men.

When I learned of El Refugio, I made a pledge to visit one day. Five years later, I made good on it. I thought of the stories inside of Stewart like a sorrowful pile, mostly forgotten or never thought about in the first place by anyone on the outside. But each story deserved to be singled out and held up to the light and examined. Each became a galaxy upon inspection.

On an icy December night in 2016, I drove from Atlanta to Lumpkin with Amilcar Valencia, his wife, Katie Beno-Valencia, and their two-year-old son, Óscar. Amilcar is the Atlanta-based executive director of El Refugio. As Óscar snoozed in his car seat, Katie and Amilcar explained visitation and their connection to this work. The couple met in the early 2000s while Katie was studying abroad in El Salvador, where Amilcar, a short man with combed-back glossy hair and black stubble, was born and raised. He joined Katie, a paralegal for a child advocacy law firm who corrals her brown curls into a ponytail, in the U.S. a few years later. Their shared Catholic faith and reverence for Jesuit religious activism drew them to migrant issues. They were part of the core team that opened El Refugio in 2010, four years after Stewart first opened its doors. They married on El Refugio’s inaugural weekend and spent their honeymoon in Lumpkin attending a vigil outside Stewart and sleeping in the house’s shared rooms.

The sharp, dry smell of raw lumber greeted us as we neared Lumpkin. Amilcar zigzagged his Ford Fiesta around the courthouse, headed south. Soon he turned into a sandy driveway and pulled behind a one-story house painted the color of banana pudding, with white shutters and a short brick stoop. We’d arrived at El Refugio. (Two years later, Comedy Central’s Samantha Bee would spotlight El Refugio. She purchased and renovated a much larger house in downtown Lumpkin and donated the building to the nonprofit.)

Amilcar entered the cold house and immediately lit the gas heaters. I admired pencil and crayon drawings made by detainees—thank-you notes heavily featuring crosses and apostolic hands wrapped in rosaries—that were taped to the fridge and pinned onto hallway walls.

The house offered three bedrooms, each outfitted with bunk beds. I helped Amilcar unfold a futon in the living room, the bed closest to the warmest heater, and Katie laid their son there. I took a small room to myself at the front of the house and flung my body onto a bottom mattress. It was late, and no cars passed outside. I looked up at the plywood sheet that held up the top bunk and saw Sharpie drawings likely made by children—smiley faces with small parabola bodies, traces of people who’d slept here before. There were scribbles on the low ceiling, too, maybe made by an older brother on the top bunk. I assigned narratives to the sketches and imagined the artists who had rested nervously here, worried and eager to see a loved one, maybe for the last time, in a visitation room the next morning. I did not feel alone. To sleep here required one to lie in the troubles of others and curl into their journeys.

The next morning, Melina Baetti arrived with her sister and two friends. They’d be staying the weekend, too, visiting detainees and helping around the house. Melina and her sister were regular volunteers for El Refugio, helping run the pen pal program, but this was their first trip to the house and the prison. Once Melina’s group had ditched their bags and claimed beds, Amilcar and Katie gathered us in the living room.

Amilcar had spent the morning writing the names of detainees, their “alien registration numbers” (the digits that identified them while in custody), and which languages the men spoke on index cards. The men had requested visits by sending a postcard to El Refugio’s P.O. Box. Amilcar splayed out the cards on a coffee table before us and allowed the group to choose who we’d visit. Melina and her sister were both native Spanish speakers, and Melina spoke French fluently, so she chose two African Francophones, including Affo, who had expressed interest in El Refugio’s pen pal program. I asked her if I could tag along.

Katie primed us for what visitation would be like. The detainees had requested these visits, but silence was natural, she said. To open the conversation, we could ask, What would you want us to share with others about your story? We should be alert for human rights violations, for medical issues or abuse by guards. If anything came up during the conversation, we could note it on the index card.

Our visits, Katie explained, might be a detainee’s only connection to the outside world while inside Stewart. Give them an opportunity to be human, not just as an immigrant or asylum seeker, Katie urged. She encouraged us to share what we learned during our visits when we returned home. Our gathered voices, she hoped, would become a megaphone.

I tripped over sentiments like that one. To believe that stories told during an extended game of telephone could crumble an empire like the prison industry felt futile. But to believe otherwise would mean abandoning all hope.

Driving south from El Refugio on a state highway, we turned right onto CCA Road. In the wide parking lot of the facility, a guard patrolled the comings and goings of visitors. Leave your cell phones in your cars, the guard instructed. We did as we were told.

We were buzzed through tall barbed-wire gates. Palmettos and rose bushes framed the building’s entrance, which opened into a lobby the size of a master bedroom. In two rows of stackable chairs, families waited for their visits, staring at walls.

A guard called our names. After being checked by a metal detector, we lined up by her cluttered desk. We asked for scrap paper and golf pencils. Nothing else was allowed.

“How long y’all in town for?” the guard asked. “Y’all with the Refugio, right?”

“Just until tomorrow,” Melina responded.

“That’s nice,” the guard said. “It’s good for them to have a visitor.”

She unlocked a steel grillage door.

For months, Affo had waxed floors, earning pennies to spend on commissary goods. At night, he listened to cries of people suffering from treatable maladies. Some detainees entertained suicidal thoughts and a few had acted on them. To stay sane, he wrote surprisingly optimistic letters to Melina. He read the letters she sent back and repeated the process. Somebody out there was listening to him. Still, receiving a call to meet a visitor on a Saturday in December surprised him. He entered the room and pressed his identification badge against a plexiglass window for our inspection. His expression asked: Am I the one you’re looking for? We smiled.

He arched an eyebrow: Are you sure?

A phone was set up on either side of the window. The guards said the phones would work fine, but the receivers crinkled words and static lopped off syllables. Melina did her best to ask questions. Affo’s responses were hushed by distortion and plastic.

“Are you cold in there?” Melina asked Affo in French, the only language they shared. “Do you have blankets?” As he answered, Affo tapped on a rectangular metal grate below the window. It was a tiny space that once allowed visitors to pass papers back and forth, for fingertips to caress and linger over friction ridges. Now, the gap was locked down. This was a no-contact facility, and we were left only with barriers.

Tall and thin, Affo, twenty-seven, wore dark blue scrubs, short sleeves rolled up over defined biceps. A shaved head had begun to spiral new growth. His beard looked pecked. The paling light of the visitation room favored none of us and the stale air flow parched our voices.

We were Affo’s first company since he’d arrived in this facility. Melina asked if he knew where he was. All he knew was he’d seen trees and pastures on his way here. By then, Affo had spent around a year in captivity. Without the aid of a lawyer, he didn’t know if he’d be able to argue for asylum. He didn’t know when or if he’d be deported back to Togo.

Melina tried to discuss topics that wouldn’t remind Affo of his incarceration at the hands of the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, but it proved impossible. Mention of his wife and kids drew a frown, so Melina pivoted to food. He lit up momentarily thinking about a cuisine that was hard to describe in terms outside his native Ewe language, one of four he spoke with ease; he couldn’t think of its equivalent in a culture outside his own. He missed fish. The food from the commissary was unrecognizable to him.

Affo told us he loved sports, but in detention, he didn’t bother with team games during brief outdoor recesses. It’s too dangerous, he said. He didn’t want to make enemies among the other detainees. If he hurt himself, busted a clavicle, for example, as one inmate had, proper medical treatment wasn’t assured. Injuries and wounds were more likely to fester than heal.

When Melina handed me the phone, I told Affo that I was Canadian, so I knew some French. I said I had no real opinion on who’s the better footballer, Ronaldo or Messi. They both had their merits.

Affo seemed tired. His eyes rarely met ours. Instead, he picked at the caulk joints where the desk met cinder block. When we hung up, a guard led Affo away and into the maze of corridors that made up the detention center. More people were locked inside than lived in the nearest town.

By visiting Affo, Melina and I had hoped to connect him to an outside world that cared, but who could say if we convinced him that anyone did? We believed that an hour of conversation might chisel away at his loneliness, but who could say if it really worked? We walked outside where the privilege of a brisk winter afternoon overwhelmed us. Affo’s story left us with proof that liberation was always mated with cruelty elsewhere, often closer than we cared to know. We felt a little less free.

The Ford Fiesta crested a hill, heading north. I watched an expanse of winter-muted pine needles roil like ocean waves toward a western horizon, Lumpkin and Stewart behind us. The highway blacktop unfurled before us and became a silence we rode for miles.

I finally broke the quiet to ask Amilcar for advice on the worries now troubling my mind. He shrugged. I said that I felt as if I’d left something behind, that I felt as if I’d fissured back at the house or perhaps in the waiting room at Stewart. I felt bicameral, like a part of me remained back in the visitation room and refused to leave without answers or purpose.

“Visitation is always the hardest for me,” Amilcar said. “I close up the house and go back home [and] we leave them inside. But they don’t leave me. At night when I sleep, I see their faces. I live with their stories.”

It sounded like being haunted, like choosing to be haunted. But what was the point? Did carrying those stories offer any sort of hope?

“Americans think they can fix everything,” Amilcar said. “As humans we want to fix, be hopeful, and encourage. But that may not be good.” What came next would be difficult, he warned, and progress would be nearly impossible to gauge. He prompted me to continue the relationships I’d started at Stewart, to go deeper into fellowship. And then he used a word—accompaniment. The term grew in popularity among church people who traveled from the U.S. to Latin America in the 1980s in order to witness violent conflicts in countries like El Salvador, where human suffering was high and often the result of the U.S. government’s anti-communism policies. The humanitarian gift these church people brought was their presence. The communities they visited didn’t only need food or water, they needed advocacy. They wanted the world to stand with them and protect them.

“Being present to the hungry, thirsty, naked and prisoners, and allowing them to be present to us, is not really so complicated,” wrote Richard A. Howard, a Jesuit who worked with Salvadoran refugees, in 1987. In Amilcar’s vision, accompaniment required people to immerse themselves in injustice, to recognize privilege and promise not to be passive with this knowledge. If protests and petitions felt inadequate, Amilcar and Katie suggested I continue the personal, human-to-human approach that I’d begun by visiting detainees. I needn’t wring my hands over it. Accompaniment, simplified, just meant being a good friend.

On a balmy night the following summer, I met up with Melina at an Atlanta taqueria. I asked about Affo, and she showed me two letters he had sent her after our visit. In the first, he sounded confident about his prospects. Worry followed: more than two hundred Africans had just been deported from Stewart, he wrote, and he didn’t know why. He asked her to pray that he would be granted asylum.

Certainty about his fate had arrived in a March letter. Affo had seen a judge. His impression of the hearing was heartbreaking and brutal—he wasn’t the type of man America wanted.

“Trump est très méchante, mais Dieu est grand, l’homme est petit, et la vie continuer,” Affo wrote. Trump is mean, but God is great, man is small, and life goes on. He expected to be deported in ninety days. He thanked Melina for all her support and thanked her husband and her “little Canadian friend.” In August, Affo returned to his home country. I felt relief that his detention had finally ended, but I knew his struggles weren’t over. If I were to follow Amilcar’s advice and go deeper into fellowship with Affo—which I wanted to do—that relationship would begin then.

Affo and I connected on social media during a week of unrest in Togo. Citizens protested in the streets, demanding free and fair elections in order to oust a sixty-year nepotistic rule. Violence met their rallies. Affo sent me photos of crowds dressed in orange and red—the colors signified opposition parties—with smoke and fire in the background, and close-ups of spent tear gas canisters and people bleeding from head wounds.

“There’s a big problem with power now,” he wrote. “They’ve arrested my friends and put them in prison.” He feared he’d be next, showing me an ID card he’d kept during his detention that labeled him a member of Parti National Panafricain, one of the opposition groups. He’d been back in Togo two days. He hadn’t yet been to see his family. He’d felt hunted. So Affo fled to Ghana. Charging his phone at cyber cafés in Accra, he sent urgent messages.

“I need you to get me asylum in Canada,” he wrote. “Quickly.”

Doing so felt impossible. I hadn’t lived in my home country in more than twenty years. But I had to try. After talking with a Canadian nonprofit, I learned that if he applied as a refugee with the United Nations, it would help him gain recommendation for resettlement in Canada. There was a UN office in Accra. I warned him of the dangers in taking this route. He would have to move into a refugee camp and might be stuck there for months, likely longer, while his case was processed. He said he’d look into it.

For a time, Affo stopped sending messages. A few months later, I checked back in.

“How are you?”

“Je suis toujours dans la merde.” I’m always in deep shit.

It was the spring of 2018, and Affo slept on the streets. He sent me a video of where he’d been living—an alley of tall grasses between two beige buildings, on a mat against a wall. Affo lived an asterisked freedom. Food could be found, but not jobs. His family had depended on his remittances from Brazil, and detention had delayed the reconciliation of a harsh truth: he’d failed them and himself. Now he refused to speak with them. He couldn’t face them penniless.

“Life in Africa is hell,” he wrote. “Prison is better than Africa. I spent seventeen months [in prison] and now I’m nearly starving.”

His new plan was to escape to Brazil. A relative was going to buy a Brazilian visa for him. Affo asked me if I could help with plane tickets once the visa arrived. I told him I couldn’t afford the whole expense—at the time, I was working two bartender jobs, writing whenever possible, finishing graduate school, and supporting a family with food stamps—but I would send him all I could. After imploring friends to chip in, I sent Affo $360 via Western Union. He ended up using it to rent a room, but soon, Affo’s thoughts returned to Canada. He shared with me a video of a Togolese man who’d walked across the U.S.-Canada border through a snow-packed forest. Frostbite had taken a few of the man’s fingers, but Affo said he was willing to take the risk to get as far away as possible from Togo. But weeks passed with no news of the visa.

Late in 2018, he started to explore other options. Trained as a tiler, he took an opportunity to produce pavers using a traditional sun-baking method. He’d be able to start a small business and support himself, but he needed start-up cash. My wife and I ran a bake sale and raised a few hundred bucks to help get him going. Weeks later, Affo sent photos of his creations: bricks in different geometric shapes, colored in ochre shades and dusty grays.

Every few days, if I didn’t reach out first, a new message from Affo arrived on Facebook. He’d given up hope on the visa. He asked after my family and wondered if I’d been able to find a full-time job. He was making a little money here and there, getting by. Our chats read more like chats.

One day Affo sent me a video for the Michael Jackson song “They Don’t Care About Us.” A classic, I said. It reminded him of Stewart, he wrote. How he’d been imprisoned for no crime. The government that I pay taxes to had doled out the punishment.

“You shouldn’t have been put in prison,” I wrote. This was likely as close to an apology as he would ever receive.

“Merci.”

Toward the end of 2019 we wished each other happy holidays. And then, for months, nothing. I began to fear the worst. After I’d left El Refugio, Affo became the first spirit to visit my waking thoughts and my dreams, as Amilcar had warned might happen. His chimeric presence had influenced me to make my politics more personal: I now reached out to migrant families in my home community, to befriend them, to perform small acts of accompaniment, to make my neighbor’s struggles my own. Affo didn’t haunt me—he motivated me. But now I fretted over whether he’d become an actual ghost.

At times I doubted Affo, prompted by journalist friends who sounded skeptical when I told them his story. They asked, Had he really been detained that long? Was he truly at risk in Togo? Then I thought back to something Katie had said a year earlier: The men in Stewart are not perfect immigrants. They are flawed, just like everyone else. A stranger needn’t be perfect for us to care about them. To act in solidarity with migrants, to accompany someone, we must first become friends. And good friends give each other a little leeway, a lot of forgiveness. Radical theologian Ada María Isasi-Díaz wrote in her essay “Solidarity: Love of Neighbor in the 1980s” that practicing friendship begins to undo the power imbalance between oppressor and oppressed. Progress didn’t occur because a person like Affo possessed a more superior morality or purity than I did. Because I listened from a privileged position, and imagined a bond between us, I mended my own isolation from feeling impotent.

I missed Affo. I began to grieve him. Then, in April 2020, more than a month into the global coronavirus pandemic, a lead appeared. I’d reached out to Affo’s Facebook friends, the ones who appeared to speak French or English, and asked if they knew of his whereabouts. One friend—who went by the handle TJ Maxx on WhatsApp—finally responded. He’d heard from Affo a week earlier. His phone broke a while back, so he was hard to reach. He’d traveled from Ghana to Burkina Faso to work and was now stuck there because of closed borders. Please tell him I’m trying to reach him, I said. TJ didn’t know when Affo would be back, or when he’d hear from him again, so he could make no promises. This wasn’t hard proof, but the news eased my panic. Affo knew I was looking for him, that I hadn’t forgotten him. I waited for my friend to call me back.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.