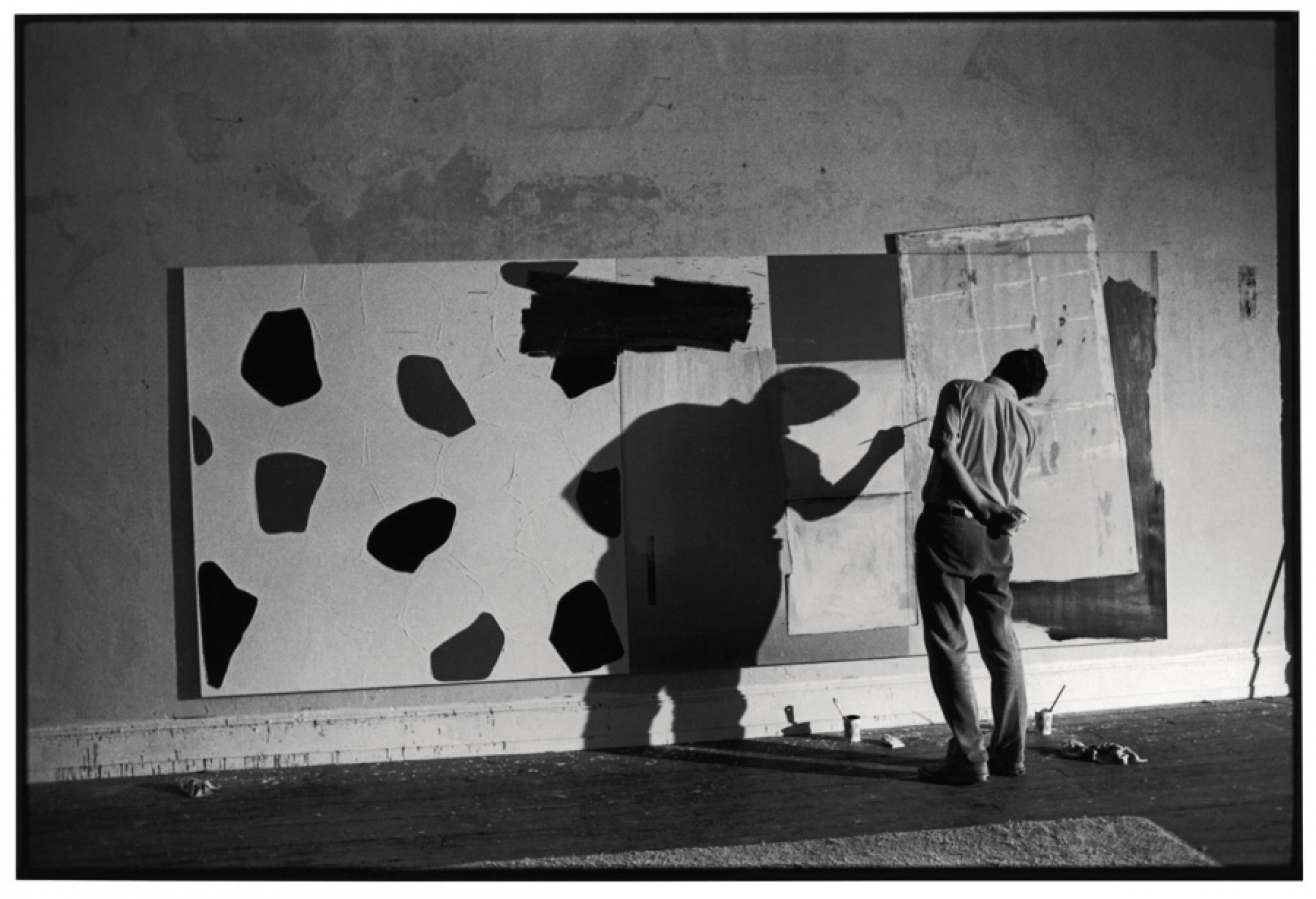

Photograph by Ugo Mulas of Jasper Johns in New York, 1967. © Ugo Mulas Heirs. All rights reserved.

The Condition of Gray Itself

By Baynard Woods

Jasper Johns, Edisto Island, and (un)color

T

he first time I saw the artist Jasper Johns’s 1962 charcoal and graphite pencil drawing Edisto, I was overwhelmed by a synesthetic memory of South Carolina, crabbing in the Store Creek, down from my great-grandmother’s decrepit house behind the Old Post Office, which her husband had run, along with the general store that gave the creek its name. Spartina grass shimmered a rigid gold in the wind-sun. Stray oyster shells stuck up through the ultra-sheened gray mud inscribed with the tiny tracks of fiddler crabs cutting angry pirouettes from hole to hole, big white claws waving. We were carrying strings we’d tie around rotten chicken necks to lure crabs toward our waiting nets.

I was only three or four and my grandmother led us down the hill with a stooped gait to the creek, her silver hair shining in the sun. At the edge of the water, I put my foot into the pluff mud—a lowcountry term for the shiny, gray muck at the edge of the saltwater tide. My foot sank and did not seem to stop sinking. I could feel the oily, unctuous mud slip cool and watery into my old canvas hand-me-down shoes in a rush that was one with the confusing, fecund smell and the overwhelming gray glare of the sun off the black water. I squealed in sensory confusion. I thought I was sinking—quicksand was a big plot point on TV in the ’70s—and a grown-up grabbed my hand and heaved my tiny body up, leaving my shoe submerged in the muck, my bare foot dripping gray mud in the summer sun.

The adults all laughed; everyone had lost a shoe to the rich, marshy mud before.

It was as if the drawing Edisto was constructed as a machine to elucidate precisely such a complex recollection.

It is a deceptively simple picture. The sole of a shoe, which is both imprinted on the paper and seemingly suspended by strings affixed to either end, creating a formal contrast with the uneven, horizontal treads. Beside it, arrows and rough dark lines suggest motion, spinning. A traced shell occupies the right corner.

Throughout his seventy-year career, Johns has forcefully avoided interpretations, because they limit our experience of a picture. An art critic who has no idea what pluff mud is may experience this picture one way. But anyone who has ever been to Edisto would bring a different set of assumptions, which would, in my case at least, begin to color (uncolor?) Johns’s subsequent focus on the color gray in his paintings.

This ambiguity is part of what is fascinating to me about the image. Ambiguity is also the defining feature of pluff mud, which—neither quite land or water—is the floor of the brackish marsh, neither fresh nor salt.

John Cage, the avant-garde composer and one of Johns’s closest friends, suggested that in the world of Jasper Johns, “we must go to a particular place in order to see what there alone there is to see.”

For years now I’ve been telling myself that I would go back to that particular place to explore the influence of Edisto on the art of Jasper Johns. I kept putting it off, but when I heard about a major retrospective with nearly five hundred works spanning the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Whitney, where there would be an entire room devoted to South Carolina, which includes not only the work he produced there but newer work reflecting on his childhood, I knew it was time to return to the island to see what there alone there is to see.

And so, in mid-February, just before the world came to a halt, eventually stalling the opening of the retrospective, I found myself there, on that same creek into which I’d sunk as a child, my face pressed close to the mud, trying to take in its odor and understand its sheen.

Johns doesn’t talk much about his life, or talk to the press much at all these days, but Cage proved to be a sympathetic chronicler. On one trip to Edisto with Johns, Cage took notes, which he later published, including a sketch of Johns’s biography, which begins, characteristically for Cage, who was a Zen Buddhist, with the fact that Johns did not remember being born.

“His earliest memories concern living with his grandparents in Allendale, South Carolina,” Cage wrote. “After the third grade in school he went to Columbia, which seemed like a big city, to live with his mother and stepfather. A year later, school finished, he went to a community on a lake called The Corner to stay with his Aunt Gladys. He thought it was for the summer but he stayed there for six years studying with his aunt who taught all the grades in one room, a school called Climax.”

The hardscrabble details in this sketch remind me of Harry Crews’s memoir A Childhood: The Biography of a Place, but it is hard to think of a writer who seems less like Johns in temperament than Crews. Crews, a hard-living practitioner of what was sometimes called “grit lit”—stories that focus on and even revel in scenes of Southern poverty—was sincere and emotional whereas Johns was ironic and intellectual.

Johns has said that, even as a child, he wanted to be an artist—only he didn’t know what an artist was. “In the place where I was a child, there were no artists and there was no art so I didn’t really know what that meant,” he said. “I think I thought it meant that I would be in a situation different from the one that I was in.”

Art was about escape. After graduating high school in Sumter, where he lived with his mother and half-siblings, he attended the University of South Carolina, which he soon quit to enroll at Parsons in New York. When he was told his work no longer warranted a merit-based scholarship, he refused one based on need, and dropped out of college. Shortly after, he was drafted into the army, which brought him back to Columbia. In the early fifties, after the army, Johns returned to New York, where he met Cage, along with Cage’s partner, the choreographer Merce Cunningham, and, most importantly, the painter Robert Rauschenberg, with whom he began an intense romantic relationship and artistic partnership. This group of New York’s new avant-garde seemed infinitely un-Southern—witty, urbane, queer—and yet Johns, the least accomplished in the group, fit in immediately.

Along with Rauschenberg, Johns carved out the space of post-Ab-Ex art, prefiguring pop art, minimalism, and conceptual art. Paintings of images so common they almost were not images at all—flags, maps, targets, numbers, along with sculptures of beer cans and flashlights—set the stage for Warhol and Lichtenstein and the other pop artists. His formal explorations—stripping away color, replacing it with the stenciled names of colors, an obsession with variations of gray—inspired countless minimalist and conceptual artists.

After his electrifying first show at Leo Castelli’s gallery in New York catapulted him to the top of the art world, Johns had a solo museum exhibition in Columbia. While he was there for the opening, he later said, it was something like a family reunion. He had been looking for a place outside of the city and that’s when one of his relatives mentioned the house on Edisto.

“Has it got a tree?” Johns asked. It did. He drove to the island, about an hour south of Charleston.

“It was December or January, very, very cold and I went inside this house, which had been locked up all winter. It was terribly cold,” Johns told an interviewer. “I went to the kitchen, and opened the cabinet below the sink and there was a half bottle of bourbon; and I said, ‘I’ll buy the house.’”

“The landscape is very different here,” Johns said of Edisto. “One moves through it differently.”

He had thought he would get more work done than he had in New York, but “it tends to be so pleasant that one doesn’t tend to work any more than one would work in New York,” he told an interviewer. “In the summer I swim, I walk in the woods, I visit friends; many friends come down, quite often, from New York and locally too.”

Initially, Rauschenberg was one of those visitors. He took a gorgeous photo in 1961 that shows Johns wearing black, walking through the yard as a woman swoops through the air on a swing made from a radial tire.

But around the time he bought the house, Johns’s long relationship and close collaboration with Rauschenberg ended.

“He breaks with Rauschenberg and, after a long time in New York, he goes back to the South at a time which is emotionally very difficult for him,” Carlos Basualdo, the curator of contemporary art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, told me on the phone. “His time in Edisto was connected to this very traumatic loss in his life. There is a narrative there of loss and desire, and it’s very deep. There’s a sense of refuge from loss.”

If Johns had started using gray as an intellectual way to “avoid the color situation,” as he put it, it eventually came to represent, for the critics at least, melancholy. “And the grisaille palette that’s so familiar in his work, frankly since the very beginning . . . does take on a sense of space and openness and maybe a sadness,” Scott Rothkopf, the Whitney’s curator, said when I called him.

At the time, the poet and critic John Ashbery saw things more formally, writing that Johns’s latest paintings were “exclusively occupied with gray—what it is, where it comes from, how it both begins and ends in light.” Johns’s gray, for Ashbery, “puts a livid sheen everywhere.”

“In Memory of My Feelings - Frank O'Hara” (1961), by Jasper Johns. Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, partial gift of Apollo Plastics Corporation, courtesy of Stefan T. Edlis and H. Gael Neeson, 1995.114.a-d. Photo © MCA Chicago. © 2020 Jasper Johns / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

“In Memory of My Feelings - Frank O'Hara” (1961), by Jasper Johns. Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, partial gift of Apollo Plastics Corporation, courtesy of Stefan T. Edlis and H. Gael Neeson, 1995.114.a-d. Photo © MCA Chicago. © 2020 Jasper Johns / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

“At every point in nature there is something to see,” Johns told Cage. “My work contains similar possibilities for the changing focus of the eye.”

As I drove and walked around the island, the focus of my eye changed and I noticed little, unconscious nods to Johns everywhere. The Edisto Island Mattress Tree, one of Edisto’s most notable human-made landmarks—a bed, a full mattress and box springs hanging by ropes from a giant oak off of Highway 174—now strikes me as remarkably like Rauschenberg’s 1955 piece Bed, which consisted of his actual bedding, painted and mounted to the wall.

Then there were the flags. All over the island, there were pallets painted as American flags. These painted flags were the products of patriotism rather than a tribute to one of the island’s greatest artists, but they achieved the same effect: were they actual painted flags or paintings of flags?

That was precisely the question Johns had been pushing in his work up until the time he bought the house in Edisto in 1961.

“Beginning with a flag that has no space around it, that has the same size as the painting we see that it is not a painting of a flag,” Cage wrote of Johns’s most famous motif. “The roles are reversed: beginning with the flag, a painting was made.”

My mind full of such coincidental combines—the kind that would appeal to Cage, the artist of accident—I stopped by the banks of the Store Creek and walked down to smell the pluff mud. The mud clumped and lumped and exalted in micro-textures in the same way as Johns’s encaustic did in a painting like Souvenir (1964).

I did not get stuck in the mud that day—at least not in a literal way. But plenty of people do. In nearby Beaufort, the Water Search and Rescue team has to come and rescue someone several times each year.

When you do get stuck, the only escape is counterintuitive.

Naturalist and writer Charles Seabrook recounts one time when he suddenly found himself sunk up to his hips. “The mud is gripping my legs, and my sneakers are about to slip off my feet. For a fleeting instant I panic, fearful that I might sink deeper and become irretrievably stuck. But I have been in this predicament before,” he wrote. “I bend over and lie on my stomach in the mud. This somehow gives me leverage enough to wiggle my legs free, and I belly-crawl in the mud to the edge of the creek, where the mud is firmer.”

Following the creation of Edisto, Johns similarly leaned into certain ways in which he was stuck. A footprint is a lot like a flag with no background. Is it a footprint or a painting of a footprint? By nature, a footprint is already an image, one that is known. But it is directly connected to the action of a person, the stepper, the artist. It brings the gesture of the artist—which Johns had attempted to remove from his work in response to abstract expressionism, which glorified the gesture and romanticized the artist who made it—back into the painting.

This sly return of the artist to the work led Johns toward his next major development as an artist, with a series created during the time he was on Edisto, although he worked on these pieces in other locales as well, including the series 0-9, Painting Bitten By a Man, Diver, and Skin with O’Hara Poem, on which he printed his face and his hands as he had his shoe in Edisto. It looks, in fact, like the imprint of a man who had leaned forward into the mud.

It wasn’t just the mud. Everything on the island was cast with a vital, vibrating pall of gray. It was at once colorless and vivid, bright and dull, infinite and unbounded. The Spanish moss, the sky, the dirt in the cemetery, the very air around us.

I got back into my gray rental car and pulled back out onto the gray highway as the gray winter trees streamed past and I turned up the radio, thinking about how, when Cage complained that he couldn’t understand the words of the rock & roll song wafting from a record player at the Edisto house, Johns told the composer of 4'33", “That’s because you don’t listen.”

I pulled up at a big blue house set back from the road, shuttered up in an overgrown yard in the off season. After his house burned in 1966, Johns bought a place at St. Martin, in the French Virgin Islands, and started going there instead of Edisto. But he eventually built this house for his mother on the lot where his house had been. For a while it was called “The Jasper Johns” on vacation rental sites, and if you search “Jasper Johns Edisto,” it is the house and not the artist that appears first. I tried to see what he would have seen from his screened-porch studio.

The Italian photographer Ugo Mulas took a series of remarkable photos, which are included in the retrospective, of Johns in his studio on the screened porch in Edisto. Standing there by the house, I can almost see him through the grisaille mesh of the screen, gangly and loose-limbed and wearing a sweater and khakis, moving around the paintings, basking in the natural light.

To an interviewer, Johns described the way the light at this particular place affected his work. “I get up very early and go down to the studio, and work in a sort of darkness with electric light, and then as the sun comes up, I’m working with a combination of electric light and daylight, and then later you turn off the light and work by daylight. This kind of changing light condition doesn’t exist in New York.”

I thought of the painting called Studio, which features the imprint of a palmetto leaf and a screen door. “Those two indexical marks on the surface of the painting really call to mind this place,” Rothkopf of the Whitney had said of the piece, which forms the center of the South Carolina room of the exhibition.

I almost tried to cut through the brush and the short scrubby palmettos to get closer to the porch in the back, closer to its screen. I recalled Cage: “Even though in those Edisto woods you think you didn’t get a tick or ticks, you probably did,” he wrote. It wasn’t tick season, but with news of a pandemic spreading, I thought of Lyme disease and I stayed out of the brambles anyway and thought of the way Cage described evenings in the house. “Ticks removed, fresh clothes put on, something to drink, something to eat, you revive. There’s Scrabble and now chess to play and the chance to look at TV. A Dead Man. Take a skull. Cover it with paint. Rub it against canvas. Skull against canvas.”

Photograph by Ugo Mulas of Jasper Johns in New York, 1964. © Ugo Mulas Heirs. All rights reserved.

Photograph by Ugo Mulas of Jasper Johns in New York, 1964. © Ugo Mulas Heirs. All rights reserved.

Iwalked the two blocks from the house to the beach. I stood at the edge of the Atlantic watching it dissolve into the gray of the winter sky. As I turned to walk back over the dunes, I noticed my own footprints from a few minutes earlier marking the sand. I thought about In Memory of My Feelings—Frank O’Hara, a piece of fulsome, knotted streaks of gray that Johns made in honor of his friend Frank O’Hara, the gay New York poet and critic. “There’s some correspondence between O’Hara and Johns about this and the thinking of the beach as a kind of site of, potentially, desire and longing,” Rothkopf told me. The first piece was completed in 1961. In 1966, the same year that Johns’s beach house caught fire, O’Hara died in a dune buggy accident on Fire Island. In 1970, Johns completed Memory Piece (Frank O’Hara), which, Rothkopf told me, had sand from Edisto beach in it.

I stopped at the Edisto Island Museum, which is a fascinating place in the way that museums run by local historical societies are, but there was nothing about Jasper Johns in the small, eccentric collection. When I asked the two women working there about the artist’s time on the island, about John Cage and Rauschenberg and the New York avant-garde’s Edisto output, they did not seem to recognize any of the names.

As I walked around, I was reminded of something I had known but had forgotten and which had left me with questions. A centerpiece of the Historical Society’s museum is a slave cabin from the Pleasant Point plantation; in 2013, the museum donated its sister cabin to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, where it still resides. In another room is a copy of the Ordinance of Secession and framed Confederate money hanging on the wall. In a more sinister reflection of the Rauschenberg bed and the Edisto Island Mattress Tree, in one corner sat a bed, which, at the time of my visit in February, was described by the label on the wall as that of John C. Calhoun, who had said that slavery was not just a necessary evil but “a positive good.”

The South Carolina that Johns grew up in, and the South Carolina to which he returned, was a Jim Crow state. Edisto Island, which had a majority Black population, was in the midst of a civil rights struggle when Johns bought his house there in 1961.

In 1955, residents had sued the state to desegregate Edisto Beach State Park. Rather than allow African Americans to enjoy the beach there, the state simply closed the park—although the closure was only selectively enforced. In 1963, a number of Black student activists made a trip to a nearby park, informing the state that they were on the way. When riot police kept them from entering, the activists filed a discrimination suit, noting that the state’s parks were hardly “separate but equal,” as claimed. There were only three parks for Black citizens and twenty for whites. When a judge ruled in favor of the protestors, in a class action suit, the state decided to close the entire state park system. When a multi-racial group of activists went to Edisto Beach two years later, they were almost immediately arrested. The Edisto 13, as they were called, were convicted of trespassing and disturbing the peace, even though a dozen or so white people had been enjoying the supposedly closed beach when they arrived.

All of this was going on when Johns came back to Edisto, when he made his major works there and tramped around the woods with Cage searching for mushrooms. The parks were not finally integrated until 1966, the year that Johns’s house caught fire.

I wanted to know how Johns, a white man, responded to this struggle. Did the segregation surrounding him—with facilities marked “Colored”—influence his thinking on color in art?

Later, I would write to Johns, through the museums hosting the retrospective, to ask these questions but, as I was warned, I received no response.

Just before I left the museum in Edisto, I mentioned to the women behind the counter that I’d been looking for Johns’s half brother, BoBo Lee, a barbecue man and raconteur, who still lived on the island.

Oh, they knew BoBo. Everybody knew BoBo Lee.

“Three Flags” (1958), by Jasper Johns. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase with funds from the Gilman Foundation, Inc., The Lauder Foundation, A. Alfred Taubman, Laura-Lee Whittier Woods, Howard Lipman, and Ed Downe in honor of the Museum's 50th Anniversary 80.82. Art © Jasper Johns / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

“Three Flags” (1958), by Jasper Johns. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase with funds from the Gilman Foundation, Inc., The Lauder Foundation, A. Alfred Taubman, Laura-Lee Whittier Woods, Howard Lipman, and Ed Downe in honor of the Museum's 50th Anniversary 80.82. Art © Jasper Johns / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

“He’s tried his very best to get rid of his Southern heritage, Jasper has,” Robert E. “BoBo” Lee told me when we finally met on the island a few days later. “The first thing he tried to do was get to where you couldn’t tell he was from the South by talking. That was one thing that he was not proud of.”

Around these parts, Lee, a big man with pink skin, smoky eyes, gray hair, and a small white beard, might have been better known than his internationally famous

half brother.

“Everybody says I’m very artistic,” he said. “But they eat everything I do.”

For years, he had run a barbecue place on the island called Po Pigs B-B-Q. Sometime around 2013—BoBo can’t precisely recall—he moved the restaurant to a new location, one that had restrooms instead of an agreement with the service station next door that would allow customers to use their facilities. But it didn’t work out, and in late 2016, he closed the only barbecue joint on Edisto. The restaurant, he said, kept him in touch with the community. Now, he did some catering, but spent an awful lot of time talking with his dog.

While he was reluctant to discuss his half brother and did not, as he put it, want to get into any controversial subjects, he was happy to talk about art and Edisto, which he fought to protect from development through his work with the Edisto Island Open Land Trust.

We were sitting in the back corner of the SeaCow Eatery on Jungle Road, a few blocks from the house his brother had owned. He’d been at the restaurant sipping sweet tea, reading the paper, and visiting with the proprietors for a while before I walked in at the appointed time. He ordered flounder and “about six fries.”

“He wasn’t with us when I was little,” Lee, now seventy-seven, said of Johns. “He would come and go. But he was so much older than me—still is.”

“He always brought me neat presents for Christmas,” Lee said. “I remember one of them big ole toy dump trucks, but he’d filled it up with charms.”

When our food came, his plate was festooned with crispy pieces of fried flounder—and six french fries.

Jasper, Lee told me, loved to fish and went out nearly every morning during his time at Edisto.

Lee had stayed at Johns’s beach house in the summer when he worked at Marion Whaley’s store, a little beach-side convenience store, and later on a shrimp boat. Lee still sends Johns local island shrimp from time to time.

“But Jap would come and go,” he said, using one of Johns’s family nicknames. “He could stay a couple months at a time and he might be here for two days.”

It was the middle of the night when the house caught fire. Edisto’s fire department had been unable to manage it, and Johns lost a lot of work—all of which is detailed in the insurance claim that is part of the retrospective. After that, Johns all but quit coming to South Carolina.

“The latter years he just didn’t show up. He came down, you know, when Mama died. He flew in and saw her right before she died and then he came down after she died,” Lee said.

Lee has always been fascinated by his older brother’s art. His favorite work was High School Days, a sculpture of a shoe with a mirror on the toe, which, Lee said, was a joke about “looking up a girl’s skirt.”

Before we left, I told him that it seemed to me like Johns had been influenced by the sheen of the pluff mud in his use of gray.

“I learned long ago that whenever I thought I figured out something about one of his paintings, I was absolutely fucking wrong. I mean one hundred percent,” Lee said. “But I think he wants it to be like that. I think he wants everybody to feel like they understand it. But he won’t say anything about it.”

As I drove back across the Store Creek, where I’d first sunk in the pluff mud forty years earlier, I kept thinking about the Cage-like Zen wisdom of BoBo’s final statement. If you think you understand Johns’s work, you are wrong. But if you’re wrong, you are right.

I pulled off the road one last time in front of the Old Post Office and walked over to look at the mud again. I realized that the ambiguity of Johns’s work was like a gift. The drawing Edisto was a big ole dump truck on Christmas. And our interpretations and associations were the charms inside. Crouching and seeing myself reflected in the creek water, I took a deep breath and the creek’s odor of sex and death, of decay and birth, almost made me swoon beneath the staggering gray sky.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.