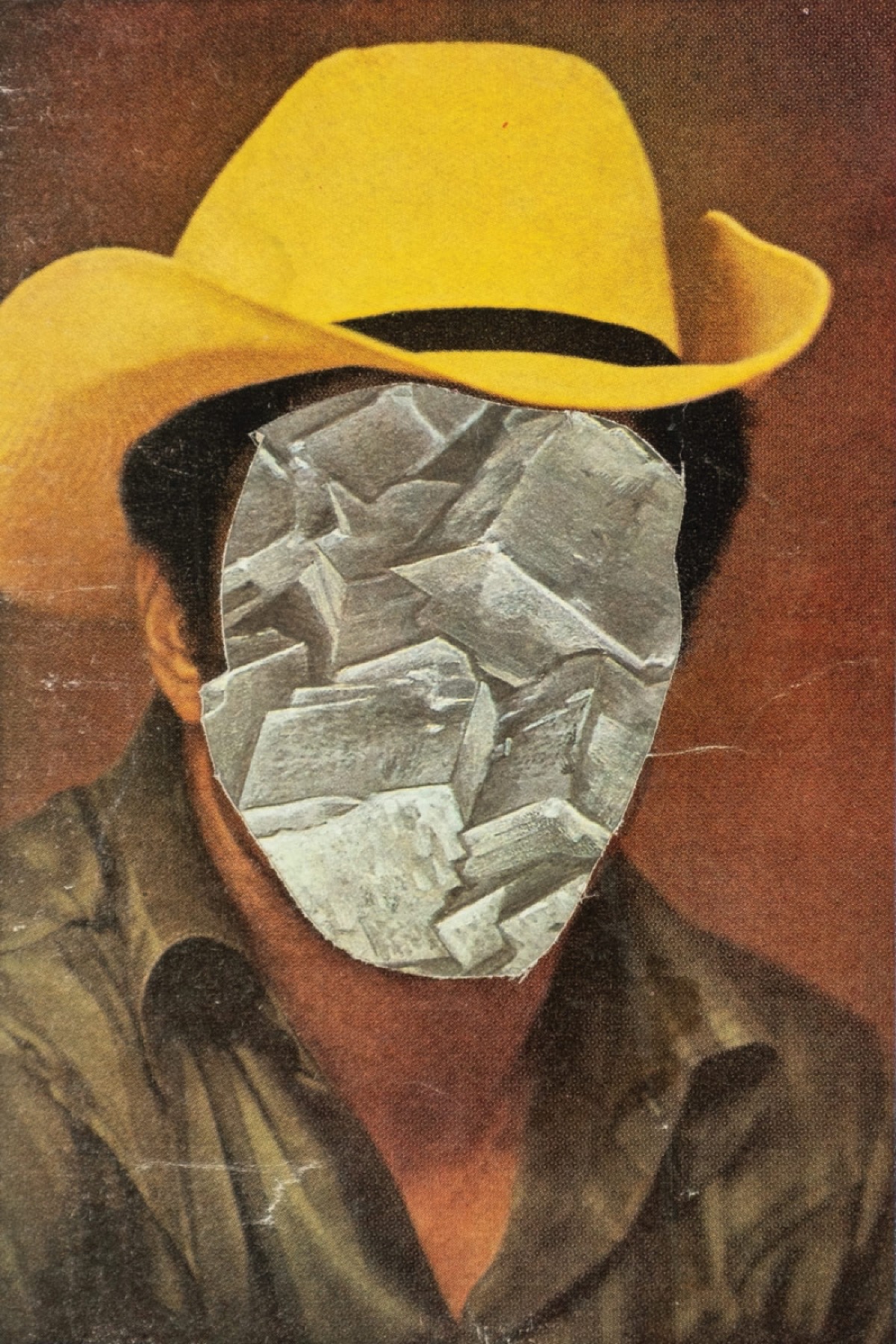

“Cowboy” (detail), 2019, by Lorna Simpson. © Lorna Simpson. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth

Finding Southern Comfort

By Valerie Boyd

Editor’s note: This essay was originally published in Spring 1999 (Issue 26). “The Great Call,” a companion to this essay, appears here.

I didn’t vote for my town’s first black mayor. The truth is, I didn’t vote in the Stone Mountain, Georgia, election at all. I didn’t even know what the issues were, let alone that one of the candidates was black.

My attention was focused more on the mayoral election in nearby Atlanta—where two African-American candidates battled it out—because I grew up there, and it’s where my parents still live.

But now I live in Stone Mountain, a suburb on the outskirts of Atlanta. Folks who know about Stone Mountain’s history of Ku Klux Klan rallies and Confederate celebrations are often surprised when they learn of my address. “I know Stone Mountain has changed,” one acquaintance remarked, “but has it changed that much?”

Apparently so, if I am any indication.

I am a young black feminist writer. I meditate every morning and have a picture of my guru, an Indian woman, on the dashboard of my sportscar. My bookshelves are crowded with titles by my favorite writers—such women as Zora Neale Hurston, Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, Gloria Naylor, and Paule Marshall. I have dreadlocks that reach the middle of my back, and I work at home most days. My music of choice is either jazz or Sanskrit chanting.

And I feel completely comfortable in Stone Mountain.

Ten years ago, I was afraid to drive alone at night to Stone Mountain. I remember an argument I had with my friend Stacey about it. She was the one living in Stone Mountain then, and I was living in the heart of one of Atlanta’s oldest black communities—the West End—just a few miles from the neighborhood where I’d grown up. Stacey and I were planning to get together that evening, but we didn’t feel like doing the usual: meeting at a restaurant halfway between her apartment and mine (about a twenty-five-mile gap).

“Why don’t you come to my place?” she suggested. “You never come out here.”

She was right, but I was stubborn. “You know it’s dangerous for us to be seen on the streets there after dark,” I half-joked.

Her chuckle barely masked a serious undertone. “That’s not true. Stone Mountain isn’t like that anymore.”

“If you pull up into the wrong driveway, I bet you’ll get a blast from the past,” I said.

“Oh, c’mon. You’re not afraid to come out here—are you?”

I didn’t want to admit my fear, but my voice betrayed me. “I’m not going to risk getting lost in Stone Mountain after dark,” I said resolutely.

A moment of silence followed. Stacey sighed. I sighed. We did the usual—we met halfway.

At that time, I hadn’t been to Stone Mountain since I was a kid. From the time I was about five years old until I was twelve or thirteen, my parents and my two brothers and I would go to Stone Mountain Park every summer for an all-day outing.

Sometimes we’d hike up the trail to the top of the granite mountain that gives the city its name. Or, when my mom said she was too tired for the rigorous mile-long walk, we’d ride a ski lift up, have lunch on the mountaintop, and then we kids would walk down while my parents returned by the lift.

I was aware of the giant relief sculpture of three white men carved into the mountainside, but I wasn’t sure who the men on the monolith were. I knew they were heroes of some war, but my parents never told me more than that.

The park’s giftshop did a brisk business selling all kinds of mementos—including some that spouted disparaging remarks about Yankees. As soon as I was able to read the insults, I asked my father who the Yankees were. He told me they were Northerners, explaining that Northerners and Southerners were enemies, especially during the Silver War—or at least that’s what my young ears heard.

My favorite part of these outings was the train ride through the 3,500-acre park. As the languid locomotive circled the mountain in the park’s center, the tour guide, dressed as a cowboy, would warn passengers to look out for Indians. “If y’all ain’t careful,” the young white cowboy warned in an exaggerated Southern dialect, “them Injuns might scalp ya.”

A part of me knew it was all a show, but another part genuinely feared the wild, yelping, paint-faced Indians. Never mind that some of the “Indians” greatly resembled the white teenage cowboys. Never mind my parents’ assurance that the cowboys and Indians were only actors. For the moment, this was real. And this was war.

Once, my older brother even tried to trip some of the Indians. He later bragged of his bravery to his eleven-year-old cronies. He had just been doing his part to help “our side” win.

By “our side,” of course, he meant the cowboys.

A few years later, as I began to learn more about American history, I realized that the cowboys were not on our side. They had helped to destroy the American Indians, and the Indians were usually friendly with black people, my eighth-grade history teacher said. I remember it was the eighth grade because that was the year ABC aired Roots, the television miniseries. I’ll never forget a discussion we had in class after the first night’s episode. My friend Michelle just couldn’t believe slavery had happened the way Roots depicted it. There’s no way it could have been that brutal, she said. All the raping and the beating, that was just something they made up for TV.

When some of us explained to her—as our parents had explained to us the night before—that some black people had lighter skin than others because of miscegenation (a word I learned from my English teacher), Michelle was outraged.

“You’re lying,” she said.

“No, it’s true,” I countered. “A lot of the white slave owners raped the black women, the African women, and they had children who were half-white. That’s how so many of us became light-skinned.”

“l don’t believe that,” Michelle said, her gray-brown eyes turning steely with indignation, her own light skin turning red.

Our teacher, Mrs. Turner, had been quiet during most of this discussion. Now we all looked to her for clarity. She nodded her head slowly, almost reluctantly.

“Yes, that’s the way it happened,” she said.

Michelle was furious. “I don’t believe that,” she said, shaking her head firmly and crossing her arms in front of her.

Along with learning more about slavery and the Civil War, I also realized that Stone Mountain Park was a memorial to a way of life that had limited use for people like us.

The mountain sculpture memorializes Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis, and Stonewall Jackson. These men were Southerners like me, yes, but as Confederate soldiers they had fought to keep black people—like me—enslaved. That’s what the Civil War was all about, my teacher said.

I confronted my parents with my discovery. “Did y’all know that Stone Mountain was racist?”

“What do you mean, ‘racist’?” my mom asked.

“I mean, the Confederate soldiers—like the men carved on the side of the mountain—fought to keep black people in slavery.”

“Is that so?” my mother asked nonchalantly.

My dad stepped in. “Yeah, you know that’s why the Ku Kluxers burn a cross on the mountain every year around Labor Day.”

“They usually burn three or four, don’t they?” my mom asked.

“Probably,” my dad answered casually.

I exploded with disbelief. “You knew about this? Why have y’all been taking us there every summer if you knew it was a racist place?”

My dad shrugged. “It’s all right to go there for a day I guess. But we always leave before it gets to be nighttime.”

“So what does that have to do with anything?” I asked in my surly, twelve-year-old way.

“We leave before nightfall, ’cause they say it’s dangerous for Negroes to be in Stone Mountain after dark.”

“For real?” I whispered.

“Yeah, some of those white folks catch you out there, no telling what they’ll do,” my mom said.

“So y’all weren’t scared? Why did we go at all?” I asked.

“I imagine it’s okay in the daytime,” my mom said.

“Plus, it’s supposed to be changing,” my dad added. “Haven’t you heard Dr. King’s ‘I Have a Dream’ speech? ‘Let freedom ring from Stone Mountain,’ he says.”

“Yeah, but that doesn’t mean it’s ringing,” I said.

We all laughed, but my parents’ laughter came more easily than mine. They both grew up in the segregated South—my mother in rural Georgia, my father in Alabama. For both of them, the big city, the land of opportunity, was Atlanta—where at least white people didn’t routinely call them “boy” or “gal” (or worse) to their faces.

Racism was real, they acknowledged, but it was just an annoying fact of life that had to be dealt with occasionally—kind of like a flat tire or a mouse in the kitchen. Nowadays, in the mid-70s, everything was “pretty equal for black and white,” my father said.

Compared with what? I wondered. I’d never seen a Klansman in person (as both my parents had), and I’d never had to drink out of a water fountain with the word colored painted above it. So I had a hard time understanding my parents’ perspective.

Happy to have this discussion with me, they didn’t notice that for the first time in her life, their only daughter had realized that there might be places she couldn’t go, things she couldn’t do, because of the color of her skin. They didn’t notice that a kind of racial fear took root in my bones that day.

Or maybe they did notice. Our family didn’t go to Stone Mountain Park that summer—or ever again.

About twenty years later, in May 1997, my parents visited my home in Stone Mountain for the first time. My mother grumbled softly about the thirty-minute drive from their house to mine, but my father was excited. When they arrived I gave them a quick tour of the four-bedroom house.

I explained that the previous owners had lived here twenty-seven years and had loved the house.

“It shows,” my mom said, noting the house’s sturdiness and well-kept condition.

“They were white folks, right?” my father asked.

“Of course,” I said. “You know black folks just started moving to Stone Mountain a few years ago.”

“Now all the white folks are moving out,” my father said.

“White flight,” I acknowledged.

“But we saw some white people down the street when we were driving over here,” my mom said.

“Yeah, there are quite a few who still live in the neighborhood,” I said, pointing out that I had several Vietnamese and Indian neighbors as well.

“Y’all just got everything over here, don’t you?” my mom asked.

“Yeah, my friend Pearl calls it ‘the San Francisco neighborhood.’”

The racial makeup of Stone Mountain started to change in the late ’80s. That’s when sizable numbers of middle-class African Americans began buying property here.

The shift has been dramatic. In 1980 Stone Mountain was 94 percent white. By 1990 the figure had dropped to 85 percent. Nine years later, half the registered voters in this town of 35,000 are black. This sea change in the town’s population coincided with a shift in my attitude. A few years after I’d flatly refused to visit my friend Stacey here, I started dating a man who lived a few blocks away from her apartment. I suddenly found myself spending quite a few Saturdays in the town I’d once shunned.

Ralph’s house was warm and spacious, and he seemed quite comfortable there. I don’t recall our ever discussing Stone Mountain’s racial history. Instead, we delighted in the proliferation of Caribbean restaurants in the area, and sampled jerk-seasoned fish and plantains wherever we found them.

Ralph and I broke up after a couple of years, so I didn’t have much reason to visit Stone Mountain anymore, but I had lost my fear of it.

So when I started looking to buy a home, Stone Mountain—with its affordable prices, quiet streets, and easy access to downtown Atlanta—was on my list.

Stone Mountain was the birthplace of the twentieth-century incarnation of the Ku Klux Klan. After Reconstruction, the Klan had been largely inactive until its rebirth in 1915 at a rally on top of the mountain.

Until his death in 1993, James R. Venable, the hate-mongering Imperial Wizard of the National Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, called Stone Mountain home.

And until 1991, Klansmen held annual rallies at the base of the mountain, where they burned three sixty-foot crosses each Labor Day weekend.

The man who stopped the rallies is the new mayor of Stone Mountain.

Chuck E. Burris had just been elected to the city council in 1991 when Venable’s daughter, according to a New York Times report, approached him with a request on behalf of her then-ailing father. She wanted to ensure that when her father died, the city wouldn’t rename the street that carried the Venable name.

Burris agreed to protect the street name if the family would no longer allow Klansmen to hold rallies on its property at the base of the mountain. The Venables agreed, and the deal was made.

After six years sans Klan, Stone Mountain elected Burris as its first black mayor. And the forty-six-year-old Burris just happens to live in the same house where Venable, who was himself the town’s mayor in the ’40s, lived for most of his life.

“Tell me,” Burris says, “that God doesn’t have a sense of humor.”

For Burris—and for me—Stone Mountain now serves as a powerful symbol of the rise of the New South. “There’s a new Klan in Stone Mountain,” Burris declares. “Only it’s spelled with a ‘c.’ C-L-A-N: Citizens Living As Neighbors.”

The New York Times, in a front-page story, trumpeted Burris’s election as “a landmark in the racial evolution of the New South,” and, more cautiously, as “a testament to the gradual easing of racial politics in some Southern communities.”

The key, cautionary word here is gradual. The scholar Farah Jasmine Griffin points out in her book “Who Set You Flowin’?”: The African-American Migration Narrative that as early as the 1930s and ’40s, forward-thinking black writers like Zora Neale Hurston portrayed the South as “a place of possibility.” For many African Americans of that era, however, the South was a place where the earth was “soggy with black people’s blood,” as Toni Morrison has written.

In a 1945 article in Negro Digest titled “What the Negro Thinks of the South,” the journalist and satirist George S. Schuyler expressed the love-hate relationship that many of his contemporaries felt toward the South:

Their thoughts about Dixie are similar to the opinion of Jews about Germany. They love the South (especially if they are Southern-born) for its beauty, its climate, its fecundity and its better ways of life; but they hate, with a bitter corroding hatred, the color prejudice, the discrimination, the violence, the crudities, the insults and humiliations, and the racial segregation of the South, and they hate all those who keep these evils alive.

Schuyler added, “A Negro who migrates South is as rare as a Jew seeking transportation to Berlin.”

Yet much has changed. Today, as Griffin notes, the Southern landscape is not only a historic site of trauma for black people but also a place rich with “possibilities for black redemption.” Many African-American cultural figures—including Toni Morrison, jazz vocalist Cassandra Wilson, hip-hop artists Arrested Development, and filmmaker Julie Dash—embrace the South, writes Griffin, as a site of “ancestral wisdom and spirituality.”

Pittsburgh-born, Seattle-based playwright August Wilson, who calls the South “our ancestral homeland,” is outspoken on this matter. “Black American culture emerged in the South,” he says. “I do not make the leap across the water. In order to find Africa, you don’t have to go back to Africa. All you have to do is go back to the South.”

That’s exactly what many African Americans are doing, according to a 1991 New York Times article on “countermigration.” And as Stone Mountain signifies, these countermigrants are returning to a different South—one filled with unprecedented economic and political opportunity.

“There is a whole generation out there whose idea of the South has very little to do with lynchings of blacks, segregation, or the Ku Klux Klan,” says Isaac Robinson, a North Carolina Central University sociologist quoted in the Times story. “They know that there is some racism, but it is not the predominant thing in their minds.”

Many countermigrants say that the small incidents of racism they occasionally encounter can be attributed to ignorance or rudeness—small stuff that’s “hardly worth a barbershop shrug,” as the critic and novelist Albert Murray puts it.

In fact, Tamara Jeffries, a friend of mine who grew up in Danville, Virginia, but who now lives in Philadelphia, says she encounters less rudeness in the South than in the North. She says she’s always surprised, on her visits South, when middle-aged, ruddy-faced white men call her “ma’am.” She doesn’t get that kind of treatment up North.

“I may tend to romanticize the good aspects of the South,” she admits, “but I think people have tended to romanticize the good aspects of the North, too. Racism exists everywhere, but in the North, they’re just nastier about it. It becomes a question of, is it better to have someone be polite to you while they discriminate against you, or to be nasty while they discriminate?”

Southern hospitality is no myth, she believes. “To just have people say hello makes all the difference,” she says. Before moving to Philadelphia about four years ago, Tamara had lived in Knoxville, Atlanta, and Hampton, Virginia.

“I miss the South,” she says, “but I don’t always realize it until I go back.” On a recent visit to Atlanta, she was maneuvering her goddaughter in a stroller and was helped, over and over, by several strangers, black and white. One man even picked up the front end of the stroller to help her get it onto an escalator. “I never got the feeling that these men were trying to hit on me, or to get money out of me. There was no sense of danger at all.” This Southern kindness, she says, “is food. I really miss it.”

Tamara, who’s thirty-four, plans to join the caravan of countermigrants and eventually move back South. She recounts a recent conversation with her mother about the pull homeward. “I want to come home,” Tamara said.

“Where? What does that mean for you?” her mother asked.

“Anywhere south of D.C.,” she answered. “And north of Atlanta.”

Tamara dreams of living in a place where she can be surrounded by trees, where she can plant a garden, where she can have easy access to church fish fries and juke joints—as well as African dance classes and multicultural events. She acknowledges that this kind of cosmopolitan diversity isn’t available everywhere in the South. “I sometimes feel that there’s sort of a dome over Atlanta,” she says, “and that everything else is unchartered territory.”

Fewer than eight years ago, she recalls, she inadvertently walked into a KKK rally in Madison, Georgia, just sixty miles east of Atlanta. She was traveling with a white colleague. “We were both sickened by the sight of the Klansmen,” she says, but she was calmed by the other black faces she saw. “People in the town were just walking around like it was no big deal. They had no fear.”

Perhaps that is the biggest difference between the Old South and the New South: black people, for the most part, have lost their fear of white people. To be sure, some very real social changes have occurred in the South over the past twenty-five years. Stone Mountain (with its first black mayor, its black-majority city council, and its newest black citizen—me) can attest to that. But the biggest change may be the quiet revolution that has occurred in the souls of black folks. Klansmen aren’t denied their right to rally, but black people, like the ones Tamara saw in Madison, Georgia, are largely unaffected by it, unmoved, unafraid.

Another friend, a Tennessean who now lives in Cleveland, Ohio, is more cynical. The only difference between the Old South and the New South, she says, is the New South has McDonald’s and Rastafarians.

But doesn’t the presence of the Rastafarians—along with countless other people with various ways of living and believing—make a difference in the feel of the South?

I believe it does. Those African Americans who feel the South calling us home are returning to our roots—but to new growth as well. We have come back home to the South to revitalize it, to refurbish it as we would an old house.

Sometimes, though, as Tamara discovered in Madison, the Old South and the New South stand awkwardly together, like two mismatched houses—one a Southern Victorian, the other a contemporary ranch built within shouting distance of each other, too close for comfort. “Specters of the past loom in the clouds,” writes Eddy L. Harris in his memoir, South of Haunted Dreams.

The South is as the South was—and always will be, though nothing is forever. The past and the present coexist here as nowhere on earth, side by side, as though one cannot live without the other, the way evil sustains good, the same too as white and black in the South are inextricably linked.

A month or so after I moved into my house, I visited Stone Mountain Park for the first time since eighth grade. I skipped the train ride and headed straight for the mountain, which rises more than five hundred feet above the Georgia plain. As I breathed in the crisp pure air, I looked down at the city below. The view is breathtaking. From where I stood, I couldn’t tell where Atlanta ended and where Stone Mountain began. It all seemed so small anyway, compared with the view of the horizon. I looked around me. The other people—people of various ethnicities—seemed oblivious to the fact that they were sitting on top of a monument to the Confederacy. Their eyes, too, were watching the horizon. At that moment, the identities of the three men carved in the granite hardly mattered (though I’d certainly prefer Martin, Malcolm, and Gandhi—or, even better, that the ancient hunk of stone hadn’t been defaced at all). For now, all that mattered was the spring breeze, the sun on our faces, the moment that was neither past nor future—the moment that was now.

A few weeks later, on a Saturday morning, my meditation was disturbed by the ringing of the doorbell. I opened my eyes reluctantly. The incense was still burning, and the calming music wanted to pull me back into meditation. A little disoriented, I got up and went to the door. Through the peephole, I saw a slightly distorted face gazing at me. It was an elderly white lady, the kind of woman who, I would imagine, cowers in elevators when whites are in the minority and clutches her purse at the sight of black men. In the ten seconds it took for me to decide if I should open the door, I wondered what she could possibly be doing on my front porch. Surely the music wasn’t too loud. Surely she wasn’t here to tell me the lawn needed to be mowed. And surely she wasn’t a Jehovah’s Witness. I opened the door cautiously. She introduced herself. She had come to welcome me to the neighborhood.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.