Vintage postcards of the Ave Maria Grotto photographed by Milton Carter

Ex Parvis Magna

By Jamie Quatro

Two summers ago, I had a panic attack on the Robert F. Kennedy Bridge in New York. I was driving my daughter to Boston for her summer internship. We’d spent the night with a friend in Brooklyn, and now we were on Grand Central Parkway, a clear June morning, not much traffic. We drove through Williamsburg and Astoria, passed a cemetery, I saw the suspension towers, and—who knows why it happened on this particular bridge?—I suddenly had the precipice-edge sense of driving into nothing. My seat, the car, road, pilings, all of it dropped away, and I was floating, unsupported, in empty space. Full-body sweat, heart rapid-firing, eyes fogging up around the edges. I’m going to pass out, I said to my daughter. I switched on the hazards, pulled into the far-right lane, and made it across the bridge going about twenty, horns blaring around me. On the other side McKenna and I traded places, and she drove till we stopped for gas in Connecticut.

I’ve since learned that the bridge spans a portion of the East River known as Hell Gate, which is fitting because my incident turned out to be a kind of panic gateway. Since that first episode, whenever I find myself approaching a bridge, the thought what if it happens again? will trigger the panic. Focus on the road in front of you, people tell me. Roll down the windows and sing at the top of your lungs.

But the fail-safe way to avoid panicking is to avoid bridges. Normally I check my routes in advance. Today I’m running late. I’m heading to Cullman, Alabama, for a weekend retreat at Saint Bernard Abbey, a Benedictine monastery founded in 1891 by German Catholic monks. I was raised Protestant, the Calvinist kind, but I’ve always been attracted to Catholicism: kneeling, standing, bells, smells, iconography. Embodied worship. I’ve learned to pray the rosary and have memorized prayers from my mother-in-law’s Catholic prayer book, bequeathed to me after her death. I sometimes attend Mass with my son’s Catholic fiancée. As a non-Catholic, however, I’m excluded from the Eucharist. Though I’ll admit I’ve pretended. Once, during a midnight Mass at the Sacré-Coeur in Paris, I filed up with the other congregants, knelt in front of the priest, and opened my mouth.

In Cullman I hope to talk to a priest or monk about becoming a Benedictine lay oblate, which wouldn’t require conversion but would allow me to join a community devoted to a life of prayer and work, ora et labora. I’m attracted to the round-the-clock rhythm of praying the liturgical hours: matins, prime, terce, sext, none, vespers, compline. Eyes on the eternal, body present in the now. On a deeper level I’m going to Saint Bernard out of a childlike yearning I hardly have words for. I want to kneel, confess, receive a blessing from a man I call Father, and who calls me Child. Why this longing to sit at the feet of a priest? A psychologist might say I didn’t receive enough affection from my own father when I was young; a Freudian analyst might say I have repressed sexual tension resulting in the need to assume a posture of submission; a theologian might say that to bow at the feet of the Eternal is the primal desire of every soul. Whatever its source, I want embodiment: connection, in a physical sense, to the divine. God-with-skin-on. If anyone can offer this, I think, the Benedictines can.

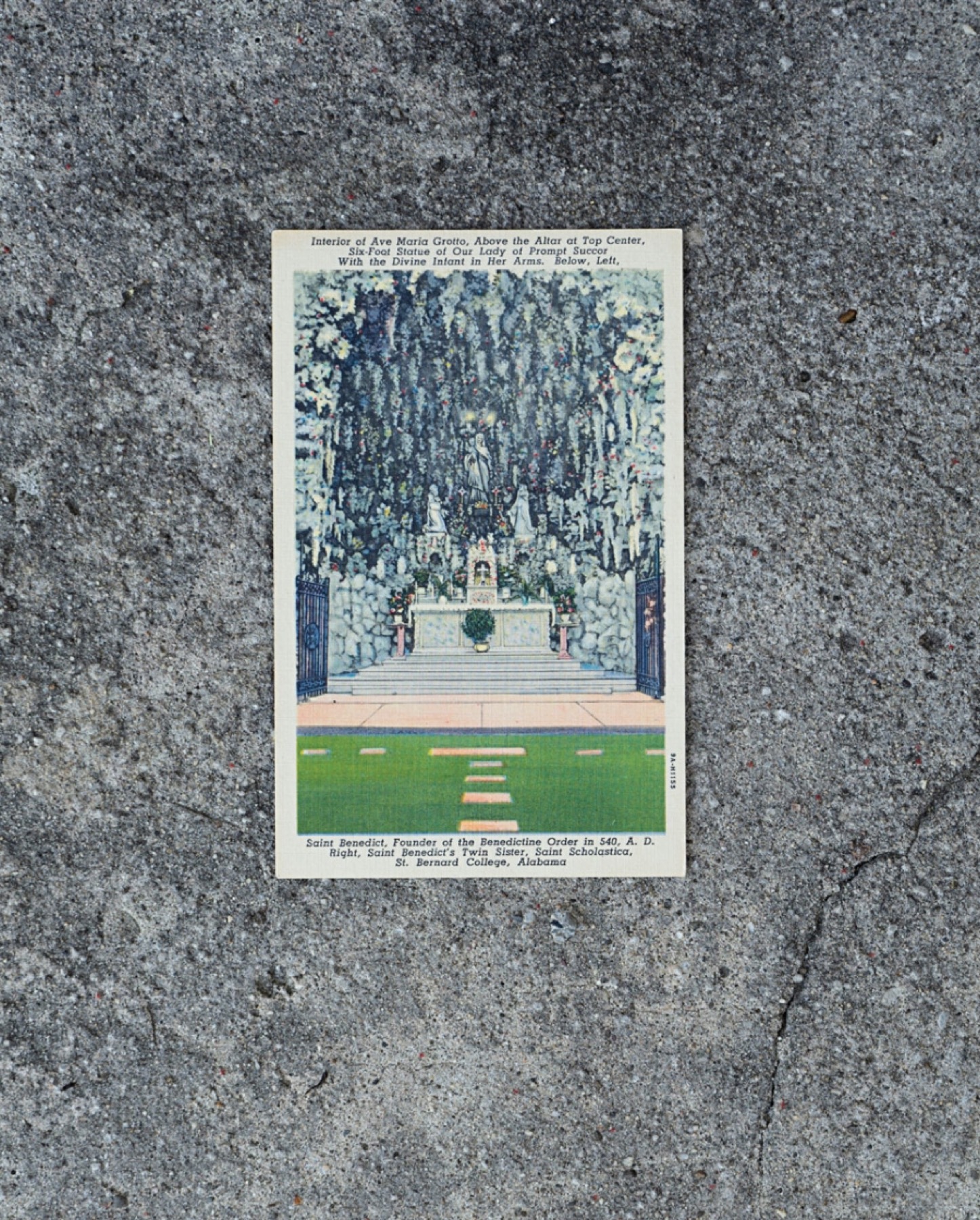

While at Saint Bernard, I also plan to visit the Ave Maria Grotto. Built on the site of a quarry on the grounds of the monastery, the grotto consists of a central “cave” housing a statue of the Virgin Mary, surrounded by one hundred and twenty-five miniature reproductions of famous buildings. A German monk named Brother Joseph Zoettl constructed the miniatures over a period of more than forty years, using only found and donated materials: stones, concrete, chicken wire, seashells, marbles, bits of glass, costume jewelry. The grotto is representative of the obsessive, visionary work typical of Southern outsider artists on the fringes of evangelicalism: artists like Howard Finster, Harry Underwood, Sister Gertrude Morgan. The fact that the visionary, in this case, was an immigrant Catholic in the Protestant South seemed strange to me, and singular.

I assume my maps app will take me on I-59 from Chattanooga, but it routes me through Scottsboro and Guntersville. Guntersville, I soon discover, is a lake. Highway 79 runs almost its full length. I realize I’m going to have to drive over a lake to get to Cullman. I can’t backtrack; I’m already going to miss the three p.m. check-in. On the first bridge I roll down the windows and focus on the road in front of me. Same with the second. No problem. The bridges are short. Some are elevated above the water, others are narrow spits of road, level with the lake on either side. And oh, it’s beautiful out, a warm afternoon in January, the water’s surface confettied gold. That liquid quality of air around large bodies of water, reflected light captured and held in a kind of supra-lake above. I feel as if I’m driving between, through, inside water. After bridge six I stop counting. Maybe this . . . well, immersion therapy is what I’ve needed all along.

Forty-five minutes outside of Cullman, I find myself facing the longest bridge yet. The panic rises. I pull over and call my husband, who stays on the line until I’ve made it to the other side.

At Saint Bernard, a friendly woman welcomes me and walks me to my assigned room. A white-haired priest in black robes paces the hallway just outside my door. “Don’t mind him, he won’t bother you,” my guide says, cryptically. I don’t tell her that I wouldn’t mind being bothered, that to speak to a priest is one of the reasons—maybe the reason—I’ve come. My room is tidy and spare: twin beds with ruby quilts, a nightstand and lamp, a desk. Other than a crucifix, the concrete walls are bare. There’s a welcome guide on the desk, with etiquette instructions for people like me, who’ve never been to a Benedictine monastery: Stand behind your chair until the monks have arrived and said the opening prayer. Dinner is to be eaten in silence. When you hear the bell at the end of the meal, stand for the concluding prayer.

The woman gives me a tour of the grounds and takes me inside the church, which is filled with yellow-orange light coming through the stained-glass window over the western entrance. Squint your eyes, the visitor’s guide says. Can you see a figure of blazing orange with arms uplifted? I squint hard but can’t see it. The floor is slate, the ceiling lined vertically with planks of pine. Huge stone parabolic arches, bone white, support the length of the church like ribs. Floating above the central altar is a ten-foot cross with the dying Christ on one side, the risen Christ on the other. Sacrifice and glory, the guide says. On the clerestory walls are limestone statues of religious figures sculpted by a German named Herbert Jogerst. I spot Melchizedek, King David, Isaiah, Saint Benedict, and Gregory the Great.

I tell the woman I plan to check out the grotto tomorrow. It’s nearly 4. Mass is at 5, Vespers at 5:30, dinner at 6. “It’s actually going to rain tomorrow,” she tells me, “so if you want to see the grotto, you might want to head over there now.”

When I was eight my parents gave me a dollhouse for Christmas. It was three stories plus an attic, had window boxes and a picket fence, and was rigged for electricity. While saving up to buy furnishings, I re-purposed ordinary objects for miniature use: a plastic strawberry container for a playpen, an upturned thimble for a trash can, my brother’s Legos wrapped in gift paper for Christmas presents. We lived in Tucson, in a low-slung adobe brick house, and I wanted to live in a house like the dollhouse, with stairs and wood-burning fireplaces and slanted rooflines. Life would be better in such a place. I didn’t actually want to live in the miniature world, of course. I wanted to inhabit a pretend life while remaining safe in the real one. “Miniatures are compelling because they are simultaneously alluring and inaccessible,” Leslie Jamison writes, reviewing Simon Garfield’s book In Miniature. “They may be subject to our manipulation, but we can’t ever go inside them. They simply aren’t big enough to hold us. . . . The miniature world doesn’t suggest total fulfilment so much as perpetual deferral, perpetual longing.” The pleasure of the dollhouse was precisely this cycle of longing and deferral: over and over, it beckoned me to enter and excluded me from entering.

It’s nearing dusk when I arrive at the grotto. The gift-shop attendant hands me the self-guided tour leaflet. “I think you’re the only one here,” she says. I wind down the path into the quarry, the light fading as I descend. I pass the Bethlehem nativity cave (dollar bills flung at the feet of the Holy Family) and come to a “Tower of Thanks,” dedicated to the “friends” who sent Brother Joseph materials for his work. It’s a structure worthy of Dr. Seuss, a concrete stalk pressed with shells and bits of glass blossoming into a cluster of round, emerald-green Irish fishing net floats, each globe cradled by what look like chameleon hands. Next is a miniature Montserrat Abbey (the monastery near Barcelona said to house an image of the Virgin carved by Saint Luke), followed by Castle Trausnitz and St. Martin’s Church, both from Brother Joseph’s hometown of Landshut, and two of the few buildings he’d seen in person.

Then comes the Statue of Liberty—perhaps commemorating Brother Joseph’s journey from Europe to America—followed by the Temple of the Fairies, into which Brother Joseph embedded a dozen cold-cream jars. In front of the temple is a tiny pipe organ bejeweled in colored rocks and costume beads. Beside the Temple of the Fairies is the Castle of the Fairies, with a ceramic Hansel and Gretel glued into the foreground. Shells and octagonal blue tiles dot the rooftops, while a watch face forms the castle’s clock tower. A long-tongued dragon with red marble eyes peeks out from the dungeon beneath. The brochure points out that he is “bound by a heavy chain, so as not to frighten children.” Brother Joseph himself affixed the chain around the dragon’s neck, after hearing that it had made a little girl cry.

Who was this man? Brother Joseph was born Michael Zoettl in 1878 in Landshut, Bavaria. When he was fourteen, a priest named Father Gammelbert came to Germany from Cullman to recruit students for the newly founded Saint Bernard Abbey. Michael sailed to America with the priest, intending to enter the priesthood in Alabama. He was small—only four foot ten as an adult—and sickly. In Germany, he’d suffered the same flu that had afflicted Thérèse of Lisieux, the Carmelite “Little Flower” who would later become Brother Joseph’s patron saint. Thérèse was devoted to the “little way” of faith—rather than heroic acts of sacrifice, she said, she would take one small step at a time, sanctifying ordinary acts on the pathway to heaven. A commitment to doing one small thing at a time would become Brother Joseph’s lifelong motto. Tragically, while Michael was helping to hoist a heavy bell at Saint Bernard, a rope broke and the jolt injured his spine. He developed cervical kyphosis, which disqualified him from joining the priesthood (the deformity was considered a “canonical impediment”). Michael became a monk instead, taking the name Joseph: in the New Testament, a figure on the margins of the holy family; in the Old, a visionary and dreamer-of-dreams. Brother Joseph was put to work in the Saint Bernard powerhouse, which provided electricity for the monastery and surrounding buildings. Because he couldn’t play sports, he began working on his miniatures as a way to pass the hours he spent alone in the powerhouse. To make the wide world small, the inaccessible accessible: this became his calling and purpose.

I enter the quarry’s basin, where the majority of Brother Joseph’s miniatures are tucked into the rocky hillside. The visual noise is overwhelming: one tiny building juts above the next in a jumble of bright colors reminiscent of hillside cities like Guanajuato, Mexico, and St. John’s, Newfoundland. I don’t know where to look. There’s an exuberance in the fixed immobility of the display. I think of Jesus’s triumphal entry into Jerusalem in the days before the last supper, the crowds shouting “Hosanna.” The disciples want them to pipe down, but Jesus says, “I tell you the truth, if they remain silent, the stones will cry out.”

I continue along the path and spot replicas of the Saint Bernard buildings, including the powerhouse where Brother Joseph worked; the Cathedral of Mobile, with domes made from discarded toilet bowl floats; Spanish missions and the Alamo; and a cylindrical structure called the Mysterious Tower in Newport, Rhode Island, fashioned from small stones and encircled by a tiny chicken-wire fence. The tower, the guide tells me, was likely built by Irish missionaries in the fourteenth century—when the Narragansett Indians were asked who built it, they replied, “fire-haired men with green eyes who sailed up the river in a ship like a gull with a broken wing.”

I encounter the part of the grotto housing the statue of Saint Thérèse of Lisieux, Brother Joseph’s patron saint. Her eyes and arms are uplifted, blossoms in each of her hands, while at her feet, a single concrete flower pressed with red and yellow marbles “grows” from a small urn. In a section devoted to Italy are the Pantheon, the Colosseum, the Leaning Tower of Pisa, and the Catacombs. Saint Peter’s Basilica dominates the scene, an old bird cage forming its central dome. And then comes the central cave, which is twenty-seven feet high. Inside is a life-size statue of Mary holding the infant Jesus, with Saint Benedict and Saint Scholastica, the twins who founded the Benedictine orders of monks and nuns, kneeling at her feet. Dozens of concrete “stalactites” jut down from the cave’s ceiling like icicles from the netherworld. Brother Joseph fashioned them from railroad spikes embedded in the mortar and wrapped in chicken wire.

On the far side of the large grotto are the biblical scenes I’d expected: the city of Jerusalem, with a reproduction of the Temple, Mount Tabor, Garden of Gethsemane, and Jacob’s Well. Farther up the path are Noah’s Ark, the tower of Babel, an Egyptian pyramid in multi-colored square tiles, the Great Wall of China, the Hanging Gardens of Babylon with plants dripping down its stone sides, tiny fonts for waterfalls, and a reflection pool not much bigger than a baby bath, filled with what I assume is rainwater.

For all its whimsy, I sense a deep loneliness, even desperation, in this place. Later I read that it was homesickness that led Brother Joseph to attempt his first architectural reproductions. When he was twenty-six, he was sent from the monastery to coal-mining camps in Stonega, Virginia, to work as a housekeeper and cook. The coal smoke made it hard to breathe, and the glowing coke ovens at night made Stonega “look like hell” to him. He grew so homesick for Cullman that he began making the buildings at Saint Bernard out of cardboard. After three difficult years in Stonega, Brother Joseph returned to Saint Bernard, the place he’d come to regard as his true home. He would stay there for the rest of his life.

Brother Joseph filed to become a U.S. citizen in 1917, when the United States was about to declare war on Germany. As a German, a Catholic, and a man living with a physical disability in the American South, he was an outsider in nearly every sense. Increasingly, too, his body was becoming a prison. He lived in nearly constant pain. His desire to re-create as many of the world’s architectural wonders as he could and cram them into this little park expresses both his enormous longing for the world and his exclusion from that world. Working only from pictures, tiny building by tiny building, Brother Joseph constructed a bridge, making his way from Cullman out to the world he’d never see.

Eventually the world came to Brother Joseph. Word spread about the tiny monk and his “little Jerusalem,” in large part due to the over five thousand miniature “house grottos” he made and sold at the behest of Father Dominic Downs, who’d purchased small statues of saints from a traveling salesman. So many people started coming to the monastery that Father Lawrence O’Leary, the guest master, said that “it became a real nuisance which could not be stopped anymore.” By 1961, the year of Brother Joseph’s death, more than sixty-five thousand people were visiting the grotto each year.

Later that evening, during Mass, I realize how exhausted I am. I’m also weirdly homesick. I don’t know all the right moves or responses, but it’s pleasant to close my eyes and listen. One monk has a beautiful trained baritone voice—he leads, the others echo. I rise, kneel, sit, rise. Around me the church seems to sway and rock, as if we’re all in a ship, safe but adrift. Belly of the whale, belly of the ark, ribs and polished pine. I feel here and not here, invited and excluded, with the nagging sense I’m only pretending to worship. Perhaps I shouldn’t have visited the grotto first, before Mass. In the grotto, the simultaneous invitation and exclusion were pleasurable: I found the tiny buildings alluring, but of course I couldn’t enter them. The exclusion was as it should be. Here, in the act of worship, that logic is upended. I’m invited to approach God, and expect to enter in, but feel shut out, empty. The exclusion is painful. I watch the monks mime three breast strikes on “my fault, my fault, my most grievous fault.” Yes, I think, my fault, this sense of being left out. I’m not Catholic, no one here knows me, and, anyhow, showing up at a monastery doesn’t guarantee a “spiritual experience.” Grace comes unbidden, not on-demand. What did I expect? When it’s time to receive the Eucharist, I cross my arms over my chest and the priest blesses me, his fingers gentle on the part of my hair. There are maybe a dozen worshippers here. I’m the only woman, and the only person who doesn’t receive the host. Wafer, wine: miniature replicas of something vast and intangible. In between, the bridge of faith to get you from bite of cracker to resurrected flesh, sip of wine to redeeming blood.

I go back to my room to change after vespers and end up arriving late to dinner. I stand by the door, wait for the prayer to end, then sit at the visitors’ table. The man across from me is reading a book. The air is heavy with the clatter of silverware and plates, the swish and scuffle of the monks filing through the buffet line. When it’s my turn to go up I find tomato soup and grilled cheese sandwiches and a good salad bar, with hard-boiled eggs and broccoli. I fill my plate and eat in silence, while behind me a monk stands at a podium and reads from something that sounds like a biography about another monk who loved baseball, or maybe played baseball. No one makes eye contact. I wish I had a book of my own.

Things get more relaxed after the closing prayer. Two monks come over to the visitors’ table and introduce themselves. “Welcome back, Chuck!” one of them says to the gentleman across from me. I bus my plates to the kitchen counter, as others are doing. I’m desperate to talk to someone, but can’t think of a single opening line for meeting a monk. The monks’ shoes are visible beneath their hemlines: Crocs, Adidas, New Balance. One monk is younger than the rest, bearded and thin. He wears Tevas. Maybe he’s the one. Hey, I like your Tevas. I panic on bridges. I should want to be here, but really, I just want to go home.

In 1954 Brother Joseph constructed one of his final replicas: the World Peace Church, the Catholic Cathedral of Hiroshima, built to express the hope that the atomic bomb would never again be used. “Our atomic age has made us more conscious of the tremendous and even mysterious power which God has stored away in little things,” the monks wrote in their remembrances of Brother Joseph. In that same year, he was examined by an internist, who wrote: “He is a well-nourished, stooped over, small, short, male, four feet ten inches tall, weighs ninety five pounds. He has a kyphosis and scoliosis to a marked degree, with convexity to the right, with corresponding distortion of the lung and heart shadows.” He completed his final miniature, the basilica of Lourdes, at the age of eighty. After that his health failed. He died three years later, his only worldly possession a copy of Saint Thérèse’s autobiography, The Story of a Soul.

Before he died, at the behest of the monks, Brother Joseph wrote some pages of autobiographical notes. At the top of one page he scrawled the phrase Ex Parvis Magna. From small things, greatness.

After dinner, the same white-haired priest is pacing the hallway outside my room. Another chance. But what to say? I clear my throat and try to make eye contact, but he rounds a corner and disappears. People go on these retreats for privacy and silence, I think. The priest is only honoring that need.

On my phone is a string of texts from our family group. My husband and two of our children are going to see a Led Zeppelin tribute band tonight. They’re going to hang out at our house and play games after.

There was a time when I would have given anything for this quiet space to reflect. As it is, I’m tired of thinking about God, and maybe the reason I can’t figure out how to talk to anyone here is because I don’t want to. What I want is to be at the Led Zeppelin tribute concert with my family. I want noise and color and sweaty human bodies crammed together. Maybe the embodiment I crave is something I’ve had all along and I simply haven’t been paying attention.

Maybe I need to come back to Saint Bernard another time, with different expectations.

I repack my bag, check the hallway to make sure the priest is gone, and close the door behind me. I consider taking the interstate. But it’s twelve minutes faster to go through Guntersville. And here’s the thing about driving over a bridge at night: you can’t see the empty space beneath you. You know it’s there, but you can forget about it. In the darkness, it’s easier to maintain faith in the solidity of the road, to focus on just the bit of asphalt in your headlights. So that’s what you do. You take it slowly, bridge by bridge, until you’re safely home.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.