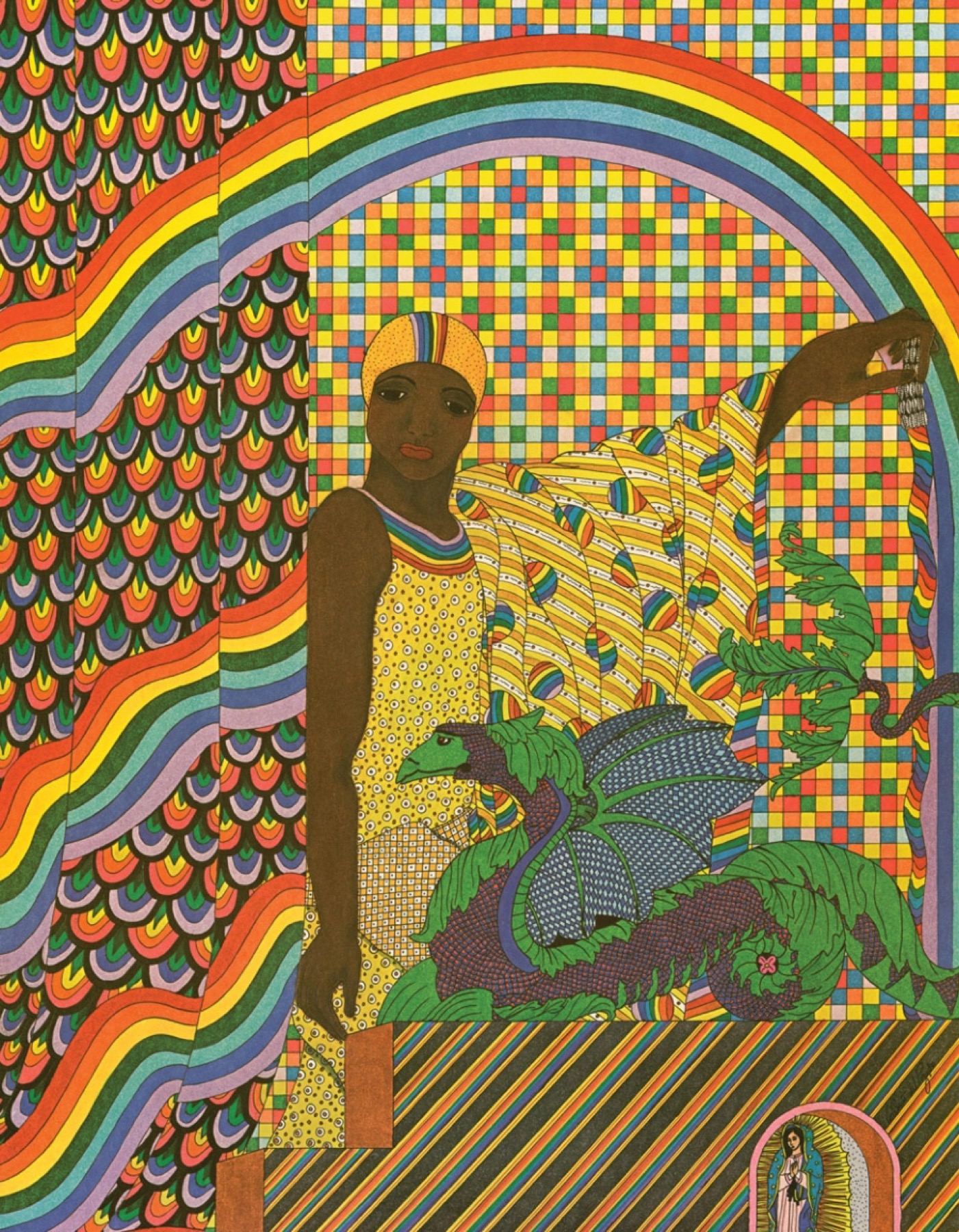

Drawing of Ochumare by Alberto del Pozo, Orichas Collection. Donated by the Campilli family in honor of Carlos Campilli. Cuban Heritage Collection, University of Miami Libraries, Coral Gables, Florida

On Sacred Ground

By Jordan Blumetti

Afro-Cuban religions find a home in Florida

“If the leaf stays long upon the soap, it will become soap.”

—Yoruba proverb

T

he world had hardly begun. During the Precambrian period—the earliest measurement of geological time, roughly seven hundred million years ago—as the glaciers melted, the seas were pumped with oxygen, trilobites outgrew and shed their armored bodies, and a layer of rhyolite and granite formed underneath the supercontinent of Gondwana, the basis of present-day Africa, which was slowly drifting east on a collision course with the supercontinent Laurentia, what would become North America. After the collision, the supercontinents split apart again, but a sliver of the western coast of Gondwana was ripped off and stuck to Laurentia. The little scrap drifting across the vast and newly flooded ocean became the foundation of the Florida peninsula.

We can thank the oil industry for this bit of geological trivia. In 1943, the Florida legislature offered prospecting oilmen a $50,000 finder’s fee to the first to discover petroleum in the state. That same year, Humble Oil and Refining Company (a forerunner of ExxonMobil) hit pay dirt in the northwest corner of the Everglades. At a depth of more than eleven thousand feet, puncturing million-year-old sedimentary rocks, the Sunniland Oil Trend became Florida’s first commercial oil well. Thousands of unproductive so-called “dry holes” were dug in the following years by hungry wildcatters. They drilled a few thousand feet at a time, beneath the limestone and sandstone, finding no oil. But they kept going, through geological epochs, from the Cenozoic down to the Paleozoic, until finally tapping the Florida Basement—a deep-seated igneous layer of granite, the backbone of the peninsula. Despite several decades of exploratory drilling, they only brought up chipped basalts and continental debris. Aggrieved oil scouts submitted a dossier of these dry holes to the state house in Tallahassee, listing every piece of equipment, location, and depth associated with each drill site—nothing more than an exceptionally detailed catalogue of their failures.

In the 1970s, perhaps as an afterthought, the oilmen started turning over their byproduct to the Florida Geological Survey—samplings that the agency would not have been able to acquire otherwise. The Survey made its own index, measuring depths and corresponding rock types, with the eventual goal of dating the material. The geologists found that this was Precambrian granite, more than half a billion years old, which meant that the Florida Basement was not related to the rest of North America, but instead matched the paleoaltitude of Western Africa. The rock shelf underlying the peninsula was a lost part of the African continent, consisting of the same rocks that can be found today on the surface of the cultural region known as Yorubaland.

“Why is Miami so weird?” Carl Hiaasen once mused. “It’s the business boosterism of the Sunbelt colliding into the Caribbean and South America, Central America, the Cubans,” he said. “It was founded by hustlers. There is a pervasive and all-encompassing greed that affects everyone here.”

The city has earned the reputation of being a strange and somewhat hostile place, hospitable only to climbing weeds, mosquitos, and millionaires. This is not untrue. I’ve lived here for the past two years and, as a rule, found it prudent to discern the motives of those who are poised to tell me otherwise. A mutant vanity and avarice exist here that push people to uncommon, unpredictable financial and physical extremes. I grew up in Venice, Florida, a leisurely, post-agricultural retirement burg, and have lived in the state for most of my life, but in no way was I prepared for a life in Miami, a city that confounds me as much today as it did the moment I (somewhat begrudgingly) arrived. After my girlfriend was admitted to a graduate program and quickly found a job at a reputable museum, I was barely consulted about the move—although I wouldn’t have had much leverage in the negotiations, not in my highly esteemed and ironclad profession of freelance culture writer. I found it difficult to adjust to all aspects of our new life, the socializing most of all. Interactions were characteristically superficial. I’d often get the question: “Where were you based before Miami?” Not “lived,” but “based,” as if I were a hedge fund, or a paper mill.

The fact that the entire metropolis of South Florida was built in the last century (the City of Miami Beach was born one year before Kirk Douglas) is a testament to human will, and tremendous stupidity. Condo units are offloaded in bulk to plutocrats, the minor royalty from São Paulo or Moscow or Caracas, resulting in ghost developments, or residential buildings with no people inside. Newly constructed, stark-white glass-front towers with no lights on. A chilly spectacle which can be experienced all over Miami, especially in the twee neighborhoods that line Biscayne Bay and the Atlantic Ocean.

A few months after my move, I was briefly contracted to write for a local business journal, which was ironic in the strict sense that I had no business writing about business. Nevertheless, I was assigned to interview the president of the Florida International Bankers Association. We sat in his office downtown, a drafty part of the city built almost entirely by shadowy foreign investors, and I asked him some perfunctory question about the current economic boom, how long he thought it would last. In what I perceived to be the most telling part of the interview, which did not get printed, he swiveled his chair around to face a window where we could see rows of empty balconies stacked on top of one another, filling the entire frame like a Gursky print. “Look at that,” he said. “Do you see any furniture?”

Aside from occasionally running around town on assignments, I spent most of my time in our crumbling apartment on South Beach, down the street from the art deco hotels that are painted like Neapolitan ice cream, their dials perennially set to spring break. Life took on the distorted tenor of a theme park. Every time I walked outside I felt like the unwelcome guest on someone else’s vacation. So I looked for points of interest, topics to write about. I attempted to make sense of the daily news and the people who make it. In Carl Hiaasen’s weekly columns in the Miami Herald, I found adroit yet snackable distillations of South Florida’s disrepute. I picked up Paradise Screwed, a collected volume, and began ingesting his columns by the handful.

One from April 1995 rose to the surface rather quickly. It was about a special “voodoo” janitorial squad on call at the Miami courthouse that would regularly clean up “messy animal sacrifices” left by the friends and family of defendants. The blood custom was apparently related to an ancient religious tradition of African and Cuban provenance. In pleasing the gods with slain offerings, the folk belief goes, there would be an auspicious legal outcome. “Let us stipulate, for the record, that no other courthouse in America has a chronic problem with nocturnal appearances by dead roosters and goats,” Hiaasen writes. He also alludes to what was at the time a recent Supreme Court decision that designated these rituals legal under the First Amendment. The case had begun in Miami, when a practitioner of the religion challenged a local ruling prohibiting animal sacrifice. The high court eventually overturned the decision. The dead animals in Hiaasen’s column had been killed under the letter of the law.

The religions were alternately billed as Haitian Voodoo, Ifá, Santería, or Palo Mayombe. And it was not so much the detail but the volume of related stories that seemed noteworthy. There were dozens of similar occurrences in Miami, reported over a span of decades. Animal carcasses were littered throughout state parks and along railroad tracks, turtles were chained together and locked with red voodoo dolls, dogs were skinned alive, chickens were cut open so family photos could be sewn inside of them. Grave robbers pillaged human remains, and a cottage industry of slaughter mills sprang up in an unincorporated frontier outpost bordering the Everglades called the C-9 Basin.

The news presented these beliefs dryly and with contempt, and I too found the idea that a slain chicken would augur favorably to be deluded and inane. The animal sacrifices appeared to be expressions of faith in something, but what, exactly? The tone of these news stories made it impossible to tell. My own prejudices were also thrown into sharp relief: I was indignant, in a distinctly moralistic way. But the eminence of the rituals made a deeper impression, suggesting something emblematic of the city; I recognized that unique brand of self-interest articulated by Hiaasen. The animal sacrifice was transactional, different from prayer, not subject to the vagaries of God but an exercise of personal volition and what specific end we wanted served, more of a formula to have one’s will reflected in the world.

I stewed on these ideas while staring out of our apartment’s flimsy casements, which never fully latched or kept out the moisture or the din outside. The building was old, and it canted noticeably toward the ocean, but the view was pleasant: bright light filled our rooms; all around were waxy seagrapes, wild monstera, and banana trees—a sultry, breathing landscape that crept into the apartment through the gaps in the windows. We were close enough to the Miami harbor that in the evening I could hear the cruise ships leaving port. They eased out to sea one at a time, as if being sent into orbit, compartment lights twinkling on the horizon like strings of broken pearls, carrying thousands of tourists south around Cuba and into the lower Caribbean, where the cruise ship companies have purchased small islands to unload their cargo for a few days at a time. As the ships idle out of the harbor, a compulsory ceremony takes place: passengers walk to the bows of the enormous vessels in their jaunty cruise wear and wave like prom queens to whoever is standing on the rock jetty at the mouth of the inlet, usually impassive waifs and fishermen. “When You Wish Upon a Star” bellows from the ships’ foghorns. Great stacks of pink and purple altocumulus formations pile up in the sky, above the empty condo towers that resemble sullen promontories guarding an abandoned coastline. If I happen to be standing on the jetty, I always wave back to the passengers, who are daffy in their contentment, as am I in obliging them.

After the initial stage of nerves and lingering anticipation that accompanies a move started to wear off, and clarity returned, my girlfriend and I began noticing an array of strange and unsettling noises coming from an apartment in the building next door. If it wasn’t heavy metal being played at a bloodcurdling decibel, it was the explosive fights between a man and woman. These weren’t your garden-variety lovers’ spats, but irresolvable and potentially criminal conflicts. Expletive-laced tirades, buffeted walls, household items sailing through the air. Our buildings are separated by a long alley where our garbage bins and a family of ill-mannered cats live. The alley amplified the noise, rattling around between the walls’ narrow canyon, with nowhere to go besides through our windows. To make matters worse, the fights almost always happened in the small hours. It seemed like every night we heard either feral caterwauling or our neighbors acting out some tortured domestic drama. And to our continued bewilderment, no one else in our apartment building cared.

Sometimes this neighbor liked to sit on his balcony two floors above, though at an angle where I could see him from the waist up. He was middle-aged and dressed in tattered clothes, a punky haircut buzzed on the sides and in the back with jagged, straw-colored bangs. He chain-smoked Marlboro Light 100s and wore fat, brown beads around his neck. He had a look about him, apparently the result of years of hard living. Occasionally I’d see him wearing a hat similar to the army-green comandante one worn by Fidel Castro. It might have even had the red star of the revolution embroidered on the front.

Whenever he was alone, we’d hear a different, but uniquely maddening noise. Click-click-click, click-click-click. It sounded like a handful of Legos or domino pieces falling on the concrete. My girlfriend and I would stand at the window, shielding ourselves behind the blinds, wondering aloud what he was doing, fiddling with something down by his feet.

After another sleepless night, I felt compelled to walk over to his apartment to say something. I stood in front of the door and was met with that distinct blend of stale tobacco, incense, and body odor strongly redolent of the headshops of my youth. I was left expecting a very specific type of person. He was indeed that person, a hard rasp to his greeting; gruff, though it turned out to be only in appearance. Without asking me who I was or why I was there, he swept his arm back, inviting me inside. Once the door was closed, he removed the cigarette from his mouth and stuck out his hand, introducing himself. Let’s call him Felix.

He wore shabby cargo shorts and a t-shirt so threadbare it was transparent. The apartment was sparsely furnished. The only pieces of furniture I could see that didn’t appear incidental were a computer desk facing the wall and a straight-backed chair. Soft afternoon light filtered through the dusty sliding-glass door.

I told him that I’d recently moved in across the alley. Before I could finish the rest of my spiel, he was already apologizing. He knew exactly why I had come, and he was pleased that I’d decided to talk to him first before calling the cops. He proceeded to unload on me the backstory of the fights, calling them tawdry and embarrassing; his current girlfriend was jealous over some business he’d recently had with his ex-wife. I was disarmed by the information, and his eagerness to offer it. I suspected he was of a certain era of punk rock, a suspicion that was confirmed when he told me he’d moved to Miami four years ago from San Francisco after his marriage fell apart, another story that was outlined for me in full color. He’d worked as a corporate webmaster in Silicon Valley, an outdated position, and regarded himself as a computer wiz, dispensing an argot of codespeak to prove his point, though he could have been speaking Singaporean patois (which he also claimed he knew) and it wouldn’t have made any difference to my provincial ear.

As I listened to the torrent of information, much of which taxed credulity, I noticed tucked away in the corner a tiered wooden shelf with a shrine-like arrangement: candles, small statues, family photographs, dried palm fronds, incense. I tried a sidelong glance even though Felix didn’t strike me as someone who would have minded if I’d openly gawked. Rather than inquiring about the strange icons, or the clicking noise, I made another clumsy appeal to him about the fights, mentioning the windows.

“It’s an old building,” I said. “We can hear everything.”

“It will not happen again, you have my word,” he said. “Next time, you’ll have to stay for a beer.”

He showed me to the door and offered a half-bow on my way out, which registered as both respectful and, upon later review, condescending.

Drawing of Osain by Alberto del Pozo, Orichas Collection. Donated by the Campilli family in honor of Carlos Campilli. Cuban Heritage Collection, University of Miami Libraries, Coral Gables, Florida

Drawing of Osain by Alberto del Pozo, Orichas Collection. Donated by the Campilli family in honor of Carlos Campilli. Cuban Heritage Collection, University of Miami Libraries, Coral Gables, Florida

A legacy South Florida reporter recently pointed out that, while the 1993 Supreme Court decision which allowed ritual killings might have been national in scope, “the practical effect was mostly limited to the chicken-killing reaches of the Florida Peninsula.” The religion he pointed to was Santería. Doubtless it owes most of its pop culture cachet to being barked by Sublime frontman Bradley Nowell in the opening lines of the song of the same name. The album “Santería” appears on, which catapulted the band into immediate international stardom, was released two months after Nowell’s death. In the music video for the song, the record company depicted him as a shirtless and proudly flabby guitar-wielding apparition looking down on his former bandmates, offering his blessing.

Santería, also called Regla de Ocha or Lucumí by its practitioners, was forged in secrecy on the sugar plantations of Cuba by syncretizing elements of tribal African spirituality with Catholicism. When West Africans were taken to the New World aboard slave ships, they brought with them the religions and customs of their homeland, now referred to as Yorubaland, a region of West Africa spanning much of the coast and interior around the modern countries of Nigeria, Togo, and Benin. Central to the belief structure is the veneration of one’s ancestors and a pantheon of African deities called orishas, which are archetypal forces of nature somewhat congruent with Greek gods, and emissaries of Oludumare, their supreme being. Santería can be described as a system of communication between man and the divine, an expression of power, or ashe, often used in times of ostensible powerlessness. There is a whiff of French Spiritism in the religion (though it predates western occultism by thousands of years), with an emphasis on supernatural dealings and rituals, communion with the dead, prescriptions, divinations, and the human body as a vehicle of spiritual force. The priests, known as babalawos, have special tools which allow them to conjure the orishas and project an unerring conviction that humans can alter their destinies, that one is not bound by kismet.

The religion spread as tens of thousands of Cuban exiles decamped to America and other parts of the Caribbean after the revolution in 1959, when Fidel Castro and his guerrillas overthrew the military dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista. Twenty years later, the Mariel Boatlift brought a second exodus of a hundred and twenty-five thousand Cuban refugees, dubbed marielitos, to the shores of South Florida. In Miami, there are tens of thousands of practitioners of not just Santería, but also the related strain of Ifá, which has the same spiritual impulse but with a different initiating orisha and a greater focus on two hundred fifty-six oral parables, or Odù Ifá, that can only be interpreted by the babalawos. In present-day Nigeria, the Yoruba religion is typically referred to as Ifá, one of the oldest theologies to have survived the late Stone Age. In a recent interview with The Fader, U.K.-born rapper 21 Savage claimed to be an initiate. “I’m an African American. I’d rather follow an African religion . . . that’s my heritage,” he said. That sentiment has been circulating among Black Nationalists and Pan-Africans since the 1950s, asserted as a measure of “cultural nationalism”—a term coined by the Nigerian scholar J. F. Ade Ajayi—marked by a turn to more authentic Yoruba traditions. In addition to Santería and Ifá, there is Palo Mayombe, or simply Palo, which comes from the Congo region of Central Africa and was formed of a similar process in Cuba.

Afro-Cuban religions seem to be more popular on a global scale than they’ve ever been. But nothing illustrates the extent to which they are practiced in Miami quite like the proliferation of botánicas—a kind of hardware-cum-horticulture-cum-pet store equipped with the devotional supplies, herbs, and animals used in constructing shrines and making offerings to the orishas. Botánicas appear in cities across the United States, anywhere that has absorbed a significant number of Afro-Latin immigrants, in strip malls or unassuming storefronts, often unmarked other than those cylindrical candles with pictures of Catholic saints painted on the front. West of downtown Miami and Miami Beach, where the landscape turns into a rubber-band ball of highways, sit the staunchly Latin barrios, and a botánica on every corner. All told, there are upwards of fifty spread across the city.

A few weeks after I visited Felix, I was explaining my budding interest in orisha worship to a colleague and Miami native. She suggested I stop into a botánica.

“Which one?” I asked.

“I don’t know,” she said. “Just pick one.”

I did, indiscriminately, on a side street off Calle Ocho—the main artery running through Little Havana, which hums at all hours with dance halls, cafecito counters, and Buena Vista Social Club sound-alikes. Inside, there was the peculiar liturgical smell of breu resin incense mixed with the yellow straw that lines a chicken coop. I saw rows upon rows of statues, herbs, and trinkets—a carnival of icons from across the Abrahamic and African spectrum, shiny Catholic idols with black faces, African baby heads with cowrie shells for eyes, bejeweled crowns and deer antlers. In a freezer, what appeared to be de-shelled turtles were for sale. A laminated flyer on the side of a vending machine advertised devotional starter kits for aspiring santeros and paleros complete with cauldron or temple jar, dried fish, shells, oils, and herbs. A four-four reggaeton beat screeched through tinny speakers.

A young man walked out from behind plastic curtains to greet me. He wore thick yellow kitchen gloves that covered his forearms and was loath to shake my hand, or have me touch him at all, for sanitary reasons, I inferred. We opted for an elbow bump, and he introduced himself as Tata Luis. Pale, moon-faced, perspiring, he had around his neck scribbled tattoos that were fading or not done convincingly to begin with. He followed me down one of the aisles and asked if he could help me find something. I said I was just nosing around. He told me his parents brought him here from Cuba when he was a boy, but before he left he was “scratched with the spirits of the Congo.” In other words, the life of a Palo priest had been chosen for him. He was working at the botánica temporarily. In two months he’d be heading into an initiation ritual where he’d have to wear white for an entire year and could not work. He wasn’t at liberty to share details beyond that, not that I would have been able to make sense of them anyway, he said, adding, “You could spend your entire lifetime and still never fully understand this religion.”

What is known of the process by which Afro-Cuban religions were formed and how they were practiced is limited to the work of precious few Cuban folklorists. Perhaps no one shines brighter than Lydia Cabrera—a spirited, and by all accounts wily, artist, writer, and rogue ethnographer born in Havana in 1899. For reasons that remain opaque, she was granted entry into hermetic African communities in Cuba, including the Abakuá, by far the most secretive and fraternal. She spent time with Santería and Palo priests and priestesses on plantations and in their homes, eventually writing her book El Monte (The Sacred Bush), arranged as a compendium of religious law and custom for orisha worship. Though she never professed to being an initiate herself, Cabrera’s writing would end up being the vade mecum for future generations of practitioners. She was eventually exiled to America following the revolution and lived out the rest of her days in Miami, though she admitted hating the city as much as she hated Castro.

There was also Miguel Barnet, a young Cuban ethnographer and writer who remained on the island after the revolutionaries took power. In 1963, he wandered into a nursing home in Havana filled with veterans of the Cuban War of Independence whiling away hours at domino tables and in front of televisions. Barnet was looking for a man he’d read about in the local newspaper, a one-hundred-and-three-year-old former enslaved person called Esteban Montejo, the son of West African parents. Montejo was born on a sugar plantation in 1860 but ran away as a teen and lived in a maroon in the woods, reemerging in 1886, when slavery was abolished. He fought alongside Cuban nationals during the war in 1895, witnessed the subsequent takeover of Cuba by the United States, and, as an elderly man, found purpose in the Castro vanguard. Montejo was “an authentic actor in the progress of Cuban society,” wrote Barnet, present at every impasse, a Zelig who had come fully formed. Barnet conducted interviews with Montejo over the course of three years. Eventually he edited the exchange and published it under the title Biografía de un Cimarrón (Biography of a Runaway Slave) in 1966. It became a singular text in Cuban studies, the first of its kind.

Montejo’s father was a Lucumí, the Spanish transliteration ascribed to enslaved people who came from West Africa—which at the time was marked on European maps as the Kingdom of Lucumí or Lukumí, Ulkumi, Olùkùmi, or Lacomie, depending on whom you asked—before it was universally regarded as Yorubaland. At their point of arrival in Cuba, Africans were assigned nationalities, or naciones, by the Spanish so they could be easily distinguished by language and ethnicity. The idea that Africans lived in nation-states or thought of themselves as ethnically distinct from their neighbors prior to colonization was itself a colonial projection, but in Montejo’s day, some three hundred years after the first slave ships arrived on the shores of Cuba, West Africans had begun to willfully identify the title Lucumí with every part of their culture, including their religion.

From the late 1700s until slavery was abolished, exports for Cuba’s sugar mill increased six-fold and the number of operative sugar plantations doubled. The growth of slave labor in the colony was commensurate. At age ten, Montejo was forced to work as a mule driver at the Flor de Sagua sugar plantation in central Cuba. He reflects on his early life in the barracoon, a fetid, flea-infested wooden barracks that housed the plantation’s two hundred enslaved people. “The barracoon was bare dirt, empty, and lonely. A black man couldn’t get used to that. Blacks like trees, woods . . . Africa was full of trees: ceiba, cedar, banyan.”

It’s clear from the beginning of the Biografía that Montejo had a world-worn, poetic sense of proportion and inquiry. “Everything about nature seems obscure to me, and the gods even more,” he says. Later, on the topic of never having met his parents, he remarks: “What is true can’t be sad.” For enslaved people, religion was a refuge. Practicing it in secret, thus evading the watchful gaze of overseers and guards, they recouped some power under the most miserable personal circumstances. Montejo’s account provides a glimpse of religious life on Cuban plantations, how the rituals and rites were performed and how they became syncretized.

“I knew about two African religions in the barracoons, the Lucumí and the Conga,” he said. “The Lucumís are more allied to the saints and to God. . . . The old Lucumís would lock themselves in the rooms of the barracoon, and they would clean the evil a person had done out of him.”

Lucumí priests, “the old Lucumís,” were then, as they are today, called babalawos. The babalawo uses an opele chain, palm seeds or coconut shells, and a wooden board covered with termite dust to commune with the orishas and divine the future. The orishas transmit their message through the divination board, providing answers to worldly problems in exchange for food offerings or, in dire situations, livestock. “If the future held good news, the priest would call out Alafia,” meaning peace, Montejo says, “to let the barracoon know that there had not been a tragedy on that day.” The Lucumís kept wooden figurines locked in the barracoon. On the walls they made markings with charcoal and whitewash, images of Obatalá (god of heavy thinkers), Shango (god of fire and lightning), and Yemayá (goddess of water and creation).

Montejo’s own language reveals that by the late nineteenth century, the term Lucumí was already being used interchangeably with what would become the far more common appellation, Santería: “The fiestas in the Casas de Santería were very good. Only black people went there. . . . As the years went by things changed. Today you can see a white babalao priest with red cheeks. But it was different then, because Santería is an African religion.” He describes these parties and rituals further, saying that the civil guards who watched over the barracoons would often pass by the celebrations and ask about the commotion. In response: “‘Here we are, celebrating San Juan.’ They said San Juan, but it was [orisha] Oggún . . . the god of war.” Africans used the religion of their captors to grant cover to their own spiritual practice. Catholic icons and saints became a kind of cipher for the orishas; Santa Barbara was Shango, the Virgin Mary was Yemayá. Hence, the evolution of the name Santería, which roughly translates to the worship of saints. A related evolution was occurring everywhere in the world where Africans had been forced into slavery. A slate of new religions was forged in this crucible: Candomblé in Brazil, Conjur or Hoodoo in the South Carolina and Georgia low country, Voodoo in Haiti and the Louisiana bayous.

By comparison, the Congo philosophy was far more animistic, utilitarian, and, in some regard, morally ambiguous. Eventually, the religion of the Congo people, who were the first to be sold into slavery, would become known as Palo, or Palo Mayombe—palo translating to “stick” in Spanish and mayombe derived from the geographic region along the southwestern border of the Congo Basin, home to the enormous Mayombe Forest, a point of passage between the realm of the living and the dead. In the Biografía, Montejo echoes the plantation stereotype of the enslaved Congolese as barbaric and brutish laborers. “For the work of the Conga religion they used the dead and animals,” he says. “All the Congos had their ngangas for mayombe.” The nganga is a large bin or cauldron (the palero, or Congo worshippers, actually use that word) that mixes the raw materials of earth together: dirt, plants, animal parts, and human remains. The belief is such that the palero could create his own dominion and preside over it. “The Congo was the more important [religion],” Montejo says. “At Flor de Sagua it was well known, because the witches put spells on people.” When a palero gathered dirt from under an adversary’s footstep and placed it in the nganga, “at sunset the person was quite dead. I say this because it happens that I seen it a lot during slave times.”

In Santería, the orishas will only intercede with things that are considered to be in harmony with your highest self and the rest of humanity. On the other hand, a palero does not petition the nganga; it is meant to be controlled, manipulated. It’s not difficult to see how this form of metaphysical recourse would be seductive to an enslaved person living in the barracoons of Cuba or South Carolina. “When the master punished a slave, all the others picked up a little dirt and put it in the pot. With that dirt, they vowed to bring about what they wanted. And the master fell ill or some harm came to his family, because while the dirt was in the pot, the master was a prisoner in there, and not even the devil could get him out. That was the Congo people’s revenge on the master.”

Click-click-click, click-click-click.

I poked my head through the blinds and saw Felix on his balcony, in his green cap, hunched over. I went outside and called up to him. The clicking abruptly stopped. He stood, walked to the banister, and, seeing me at the top of my stoop, offered a wary smile.

“Want to have that beer we talked about?” I asked.

“Sure, come on up.”

In his doorway I handed him a six-pack. “You probably think it’s been peaceful over here,” he said, chuckling. It was true that I hadn’t heard the fighting since our last visit. As it turned out, his girlfriend had been gone for several weeks.

We sat on the balcony and drank our beers. He lit a new cigarette off the butt of his last. I could see my apartment windows below, where I spent countless hours unable to concentrate on anything but the noise coming from this very perch. Dried house plants were scattered by our feet. In the corner, backed up against the pale-yellow stucco wall, I noticed a gray, molded-plastic bin, the generic kind you keep in a garage. I had a similar one for storing gardening tools.

He said that he’s been having trouble finding work recently. Something about a micro-shift in coding protocol that sailed clear over my head, though it was expressed with tremendous pathos and wit, qualities that once again disarmed me as I struggled not to fixate on his rags for clothes and the ravaged, strung-out look in his eyes.

Once we finished the first round of beers, I walked into the kitchen to grab us two more, passing the shrine along the way. I stopped in front of it, recognizing one of the figurines from the botánica, a small, demented monkey, with an arching, phallic horn; the buggy eyes, the inky color.

“Is this Esu?” I asked.

He stiffened. “What?”

“What is this?” I said, pointing to the statue.

“This is not Esu; this is a Thai spirit called Phra Ngan. He’s a type of perverted Buddha, but a remarkable archetype with the Nigerian Esu, or the Esu of Santería.” He stopped and furrowed his brow. “How do you know about Esu?”

“I’ve been hearing a lot about Santería since I moved here,” I said. “And I’ve done some research. I guess I’m trying to write a story about it.”

We returned to our seats on the balcony, fresh beers in hand. Felix lit another cigarette and inhaled sharply, reticent for the first time since I’d known him. He seemed to have already decided on what came next but was searching for the way to say it.

“Well, if you ever want to know about Palo, I can tell you.” He lifted his shirt, exposing his tattooed belly and a large animal claw hanging from his neck by a piece of leather. “I’m a palero.”

He nodded, as if to boldly affirm what I was seeing, and let his shirt fall back into his lap. I can’t say that I hadn’t anticipated something along these lines, but there was still a cold rush of insight, with what was a figment of my imagination becoming reality. The house lights had been flipped on.

Then he struck a severe tone. “You can’t tell anyone about this, though. It’s not the kind of thing I want the rest of my neighbors knowing. It’s just to help me and my friends.”

I agreed, offering whatever blandishment would deliver me his backstory.

It was the late nineties in San Francisco’s Lower Haight and he’d wandered into one of those Hispanic candle shops, a storefront he’d passed by a hundred times. A lumbering gentleman dressed in an open-collar sports shirt and white linen pants asked him what he was looking for. He left with a bundle of incense and herbs, plus a set of prescriptions for healing his body and his mind, which, as he recalled, were both deteriorating. He’d always had a penchant for the occult, and the Yoruba cosmology was enough to keep him stimulated. First it was Santería, which he practiced for a few years, before being drawn into Palo. The former had too many guardrails and protocols, was too hierarchical. In Palo, there was no asking for permission, no placating the gods or the babalawos; it was alchemy, only a matter of knowing the right formula, exactly what needed to be placed in the nganga—and voilà. After idealizing the structures of Santería and Ifá, he was disappointed to find that they mostly revolved around money. For that reason, he didn’t believe Palo to be inferior, but simply the product of a different culture and gestalt. Initiation costs were also wildly disparate, with Santería fetching upwards of $20,000, twenty times the amount of Palo. A move to Miami brought him closer to the center of the religions—domestically, at any rate. He wasn’t sure, though, how he would get away with feeding chickens in his apartment, or how he would perform a sacrifice in the event he hit a spell of bad luck and had to clean himself with the blood of a rooster.

We talked about the rash of grave robberies throughout Miami over the last couple of years. Most of them were blamed on Palo. But Felix said there were plenty of legal channels to acquire human remains. Websites such as Skulls Unlimited and The Bone Room. Even eBay sold them for a while, but had since stopped. The idea was that if you had a piece of an infamous Lothario, or the finger of a skilled gambler, you could draw on that energy for your own use. He likened it to the reliquaries of the Catholic Church.

Then there was his nganga. He pointed to it. The gray bin. Its lid was closed. I’d seen it from my window. Felix would dig around and pull out an item or place something inside. I thought nothing of it then, but now it stirred with energy.

“What was the clicking noise?” I asked.

“I’m throwing coconut shells,” he said. “Divining.” He asked if he was going to have a job by the end of the month, if his girlfriend was going to come back, what he might have to do to make that happen.

The sun was setting; the fog horns had sounded. In the indigo half-light, we watched a coconut shake loose from a palm tree and fall three stories, cracking on the concrete. On my way out of the apartment he reminded me once again not to tell anyone about our conversation. The request had more force behind it than last time. It was too risky, he said. If his neighbors knew, they might want to have him thrown out of the building. I returned to my side of the alley harboring his secret.

Drawing of Echú Eleguá by Alberto del Pozo, Orichas Collection. Donated by the Campilli family in honor of Carlos Campilli. Cuban Heritage Collection, University of Miami Libraries, Coral Gables, Florida

Drawing of Echú Eleguá by Alberto del Pozo, Orichas Collection. Donated by the Campilli family in honor of Carlos Campilli. Cuban Heritage Collection, University of Miami Libraries, Coral Gables, Florida

After a few hundred million years, whatever piece of Africa is left in North America is sealed under layers of striated karst and volcanic ash and heaped with silt and clay and sand from the Appalachian Mountains and the Gulf of Mexico. But if you were to dig down far enough, as happens to this day in Sunniland, you would eventually touch a part of Africa. This offers something in the form of an explanation for why, at present, so many initiates of Afro-Cuban religions are drawn to Florida, but not a complete one. In the twentieth century, the religion was opened to a mainstream audience, disseminated in anthropological books and made available for purchase in botánicas. I was still having trouble placing exactly what was driving its popularity, and what emboldened so many people who, like Felix, had no ethnic ties. So I sank back into the warm recesses of the internet and found a man by the name of Oluwo Fagbamilia.

I first encountered him in a video on YouTube. Speaking slowly, his voice nasally to the point of being nearly muted, he parsed the differences between Santería-Lucumí and Ifá; the latter he characterized as the original source of all knowledge pertaining to orisha worship, the taproot, which comes from the African continent; the former he said had been irrevocably spoiled by Catholicism and the “western worldview.” Fagbamilia had been initiated in Santería in Miami fifty years ago but transitioned to the priesthood of Ifá (known as an oluwo) after suffering some disillusionment. He says he witnessed rapacious greed coming from the Santería complex, an obsession with ego and money that only existed in the North American and Cuban traditions. He also alleged discrimination against women, prejudices based on sexual orientation, and a malevolent sociological perspective, things that he claims never existed in Yoruba culture in the thousands of years Ifá has been practiced. The idea commonly held in the Afro-Cuban community, especially in Miami, that Santería and Ifá are one and the same, was flatly wrong, he said: “You cannot practice traditional Ifá if you discriminate unilaterally against any group for any reason.”

I learned that Fagbamilia ran a commune with his wife, a priestess called Iyanifa Vassa, a few hours north of Miami, in a heavily forested part of Central Florida. The place was called the Sacred Gardens of Ola Olu, or a gift from God, and was modeled after a garden complex on the banks of the Osun River in Nigeria. Everything about their mission statement could be construed as provocative and heretical. It was a bloodless property, so animal sacrifices were no longer performed, nor was there the use of human remains. Fagbamilia had initiated dozens of openly gay men and women. Everyone was welcome, regardless of gender, sexuality, or race. I had been waiting for that final shoe to drop, because the face I watched bobbing around in my computer screen—jowly, egg-shaped, with a kind of geriatric squint—explaining a heuristic of an ancient African religion with such sanctimony and self-regard, belonged to a white man whose birth name was Philip John Neimark.

I made plans to visit the retreat after I received an email from Fagbamilia’s wife: “Alafia—Greetings with blessings for all good to come. . . . I think it is wise to invite you to experience the Sacred Orisa Gardens and feel the energy.”

Crescent City is not a city, but a little blip of a town that borders the Ocala National Forest, a massive green woodland in Central Florida, the oldest national forest east of the Mississippi. The brush is tamped down by a two-lane blacktop; on a map the lanes look like long strips of electrical tape. In the early twentieth century, the East Atlantic Railroad built up a string of towns through the interior of Florida that were made obsolete by major highways along the coast forty years later. Crescent City is one of these towns. A billboard with the face of hometown hero Chipper Jones stands outside the Little League field, as if to represent the long odds of making it out. Idling along the road leading to the Sacred Gardens, I lingered on the Depression-era gas stations and packinghouses of rusted, corrugated metal, awnings reaching toward the ground for their long sleep. Pavement turned to gravel, gravel to sand. And then I saw a squat wooden sign advertising Ola Olu, the spiritual and administrative headquarters of the Ifá Foundation, nestled among saplings.

The driveway was lined with a scrub menagerie of strange metal cryptids that seemed to be born of a sleepless mind. The largest was a rusty phoenix with wings outstretched and beak pointing skyward. Behind a copse of palmetto trees, I saw a narrow clapboard duplex with a fresh coat of royal-blue paint. A little barrel of a woman stepped out from the front door. She wore a white tunic encrusted with a plate of beads and sequins. Her graying hair had been recently darkened and accented with streaks of raven.

“Alafia,” she said. “Welcome to the heat zone.”

It was Iyanifa Vassa, high priestess of Ifá, born Barbara Vassalikakis. She had beady eyes and dark features. There was something noticeably ancient about her face—not superficially, but in its contours and broad shape, the thin half-smile—like those reconstructed by archeologists from bones found in Athenian caves.

We shook hands. Hers was large and muscular. She watched me afterward and I could tell she anticipated something further.

“When you approach a priest of Ifá, you make a connection with the earth and say Oború-Oboya,” she said, reaching down and running her hands across the sugar sand. “It means ‘May I have Orunmila’s blessing through you?’”

I touched the ground with my right hand. Vassa grabbed me and we hugged from shoulder to shoulder.

“Initiates sometimes throw themselves at the feet of a babalawo,” she said. “Everybody’s village does it a little different.”

On the ground level of the house, it was balmy, though portable air conditioners circulated pockets of cool air. I heard muttering and turned to see Fagbamilia, whom everyone called Philip or Oluwo, standing in the threshold of the bathroom: shirtless, slack-jawed, gripping the doorframe for balance. He noticed me and offered a smile, followed by a burst of awkward laughter. Vassa sidled around me and ran toward him.

“Oluwo is turning eighty this year,” she said, holding him by the armpits. She lifted a t-shirt over his head and pulled his arms through. “He’s been Ifá-ing for fifty years!”

I learned that eight years ago, Philip had a series of diabetic mini-strokes. His mind was still in good shape, until recently. He hadn’t been to a doctor in fifteen years, opting instead for a mighty diet of vitamins. He took a cabinet’s worth daily. I could tell he hadn’t the faintest idea why I was there, or who I was, for that matter.

Philip and Vassa purchased the land twenty-two years ago, ten acres of tangled palmetto and cypress and pine that they have sought to preserve, mostly by leaving it untouched. I assumed they lived on the property, but Vassa said they had a house forty miles east in a quiet beach town. Their children, who are now grown, wanted to be closer to “civilization.” She operates the Sacred Gardens as one would an experiential Airbnb. It can sleep nearly two dozen people during ceremonies and workshops.

Stepping one foot off the narrow clearing where the blue house stands is to ensnare oneself in dense Florida terrain. But other small clearings have been cut out of the brush where statues and shrines of the orishas were erected, mostly by Vassa. The gardens were built as a kind of simulacrum of the Osun-Osogbo Sacred Grove in Nigeria, a common feature of Yoruba villages prior to European contact, where devotional rituals, sacrifices, and offerings were performed. Nigeria’s Sacred Grove was restored in the 1960s. The rest became casualties of the industrialization of Nigeria and the Christian and Islamic conquests of the African continent.

A group of visitors pulled into the forecourt. Vassa welcomed them in: Tia, Brittany, and Darnell. The two women were dabbling in Santería and Ifá, and Darnell came to support his wife. They negotiated the space around Philip as though he were a china cabinet. Tia and Brittany had found out about the Sacred Gardens in Florida through the internet, just as I had. The internet has been an asset for the enterprise. The entire ecosystem of Afro-Cuban practitioners—not only in Florida, but around the world—knows about their operation because of it. Their marketing message is explicit: you can visit Africa without being vaccinated. Thousands of people have been initiated on their campus.

Of course, anyone following the religion since before the internet age would certainly recognize their faces. In the early nineties, Philip was the subject of folksy features in the Chicago Tribune and Psychology Today: the story of a lapsed Jew’s unconventional approach to regaining his faith in the infinite. Both Philip and Vassa appeared on The Jerry Springer Show to argue about religious freedoms and animal sacrifice with Evangelical Christians—Philip resplendent in a custom dashiki and Vassa, his third wife, in one of her many prized Versace suits. At the time, their religious practice still incorporated the ritual, and Philip reasoned that it was no different than the shochtim he grew up with. They lived in a three-story brownstone on Ontario Street in Chicago, where Philip’s practice as a babalawo slowly began to eclipse his role in the clearinghouse. Philip was a millionaire by age thirty—which I’d already known from my research before the trip, though Vassa reminded me of it in person. He drove antique Jaguars. Vassa was preoccupied with this period of her life, taking care that I registered how good it all sounded. Our conversations always looped back to money in a way familiar to people who grew up without it, as she did in North Miami, where she met Philip while working at a cocktail club he frequented.

By dint of Philip’s deteriorating condition, Vassa had assumed control of this entire operation, perhaps an unlikely position for her. Santería-Lucumí has been known to foster discriminatory policies against women, as outlined in one of Philip’s many YouTube missives. But Vassa had been preparing for thirty years, sitting alongside Philip as he worked, his equal.

“Things have changed,” she said, “but we’re adjusting. Isn’t that right?” She turned to Philip, smiling. “Yup!” he responded, absently.

We walked out into the late summer heat. Cicadas whirred; the gravel crunched underfoot. Vassa designed and constructed each of the statues out of concrete, plaster, rebar, and chicken wire. They looked like what you might find in the sketchbook of a UFOlogist. We stopped in front of a towering, vaguely anthropomorphic demigod, a figure with an alien condor head, an hourglass-shaped body, and six spindly arms reaching toward the sun: “To receive the universal intellect, ancestral wisdom,” she said, “downloaded from the heavens and transmitted to the terrestrial plane.” She had us link arms and walk in circles around the base of the statue as she chanted.

The rest of the orisha shrines had their own space cut out of the brush. We walked toward the shrine of Esu—a conical mound of hardened soil, cowrie shells for eyes, the bull’s horn rising out of its head and drooping to one side like a waning erection. It had three half-smoked cigars sticking out of its oversized ceramic lips, which lent the dual impression of a cubist sculpture and Mr. Potato Head. Vassa held out a plastic bin of dry goods for offerings: Captain Morgan rum, corn kernels, rosewater, and honey. She took a squirt of honey in her hands and ran it across Esu’s lips, “for sweetness in our lives.” She gave Brittany a small hand drum and asked her to beat it.

Vassa explained that sacred gardens represented an intermediary between the orishas and the physical world, an accumulation of ashe—the positive, eternal energy on earth—and referred to Ola Olu as the only complete orisha garden in North America, attracting disciples from all over the world, carrying their offerings for the gods. But the land itself had a little extra magic in its molecules, as it was once inhabited by runaway slaves and Native Americans who founded mixed settlements.

“You see a lot of spirits if you stay here at night,” she said. “You’ll hear drumming, flutes, the music of Africans and Indians. You can feel the vibration.” She grabbed a handful of soil. For years, they’ve sold vials of it on the Ifá Foundation website. “This land was part of the African continent. The soil and plants here are part of Africa. Nigerians often come to visit and say that it feels like home.”

Vassa carried a plastic shopping bag full of eggplants to the backyard of the house, where more shrines overlooked a small lake. Storm clouds gathered above us, and a low rumble of thunder sent a plump of geese flapping into the trees. A rickety dock meandered out to the center of the lake, whose placid surface was oil-slick, an exact mirror of the sky. While peeling the produce stickers off the eggplants, she said she was trying to advance negotiations with Veterans Affairs that would subsidize the treatment of PTSD for ex-military. People often came to the Sacred Gardens to engage with some past-life regressive therapy.

Her divination yesterday said she needed to place nine eggplants on the shrine of Oya. “Eggplants are the fuel for change,” she said. “It would just give Ifá a better name if we could get a legitimate organization to recognize us.” One by one, she held the vegetables in her hands, closed her eyes and breathed on the fat part, then reached to the ground and set them on a bed of pine needles.

Lightning flashed across the sky as we followed her into a circular grove of banana trees. In the center was a stone water fountain holding a shallow pool of slime-green water. “I love when the wind rustles the pines,” Vassa said, without looking up. The fire was for our ancestors, she explained, piling crackers, brown rice, ghee, and dried cow dung on a copper pan in the center of the fountain. She passed us a piece of the dung. It was brittle, thin as a matzo cracker, and smelled like wet sawgrass. “It’s sacred,” she said. But what here isn’t? She lit a piece of twine as kindling. A gust of wind carried the trail of smoke toward the house and, faintly, I heard Philip yell something from inside. The thunder picked up, as did a pinprick drizzle. The fire grew, flames licking in the wind. The next moment I saw that the sky had gone almost completely dark, as if a black scrim had been pulled over it. The wind was howling now, and Vassa howled back: “Oya! Oya!” she chanted. The rest of us tried to shield ourselves from the quickening rain. Her voice wavered when she heard Philip. He was screaming from inside the house.

“We’re here! We’re okay!” Vassa yelled back, but it didn’t soothe him.

Before birth we are assigned a guardian ancestor, when the spirit of a member of our family returns at the moment of conception to guide us through life. That is what the Yoruba wisdom says of reincarnation. Before I left the Sacred Gardens, Vassa gave me a reading to find out who mine was. She took out her divination board sprinkled with termite dust, the palm nuts, the opele chain, and threw the question up to the gods. “Is Jordan’s guardian ancestor his maternal great-grandmother?” Click-click-click, click-click-click. The pieces fell on the board in quick succession. She studied the pattern, and then clapped her hands. “First try—alright!” Vassa told me that I needed to find out everything I could about the woman, especially how she died. Set up an altar for her, she said, and offer her herbs and amulets. “Never feel alone, because your guardian ancestor is always with you.”

I made calls to what few relatives were left who might know something about her, but nobody had any answers beyond what I already knew, which was not a happy story: sometime between world wars, she immigrated to New York City from the hinterlands of Austria-Hungary with her mother. Together they cleaned brownstones in Manhattan and lived in a part of the East Village where they could get away with only speaking Yiddish. She met my great-grandfather and had five kids in a hurry. When he was shot and killed in a bar fight, she had to give the children up. That’s where the story ends. There are no photos, no death certificate, nothing to corroborate her existence. All her children are now deceased and none of their children, including my mother, thought to ask what happened to her, out of respect maybe, but probably indifference. Was it fair to think that this woman, if she is anything more than dirt and mercury fillings by now, was somehow wed to me? Part of me hoped she was off doing something more fulfilling.

A few weeks after I returned from the Sacred Gardens, I was referred to Martin Tsang, an anthropologist at the University of Miami who specializes in Afro-Cuban religion and orisha worship. He agreed to meet me and suggested the Cuban Memorial Park in Little Havana. On the day of our meeting, he canceled, so I went by myself and stood at the entrance looking up at statues—a bronze infantryman positioned like a toy soldier, the bust of a dissident poet. A torch was lit on top of a granite obelisk, the monument to the 2506th Brigade, who fought in the botched Bay of Pigs invasion. A LOS MÁRTIRES DE LA BRIGADE DE ASALTO, the statue read, the eternal flame of exile burning above.

The park is set in a wide median on a boulevard lined with turtle oaks and clay-shingled barrio homes. Two Cuban men stood on the sidewalk, wearing only pajama bottoms and slippers, glowering at the few tourists who had wandered over from Little Havana’s lighter cultural fare, such as the landmark Domino Park, which has become something of a global attraction; day or night, clumps of sightseers gather around the wizened domino players who have not stopped shouting at one another, about baseball or politics or some imperceptible rule violation, over the clinking of enamel tiles since they first arrived in America. Farther back in the park is a statue of the Madonna, plates of spoiled food and dried roses at her feet. Once a day she is supposedly exalted in a single shaft of holy sunlight.

The center of the park, both physically and symbolically, is the grand ceiba tree. The ochre-colored barrel trunk, which is barbed with tiny spikes, sits on long buttress roots that run out toward the pavement like tributaries. A muddy waterfall turned to stone by a mercurial god. I caught a whiff of rotten fowl as I approached the base of the tree. Against the trunk I saw a dead chicken tied up in a plastic shopping bag, its rubbery legs poking out of an opening around the knot. A half-dozen eggs were cracked in a pile next to it. The yolks had congealed with bits of dirt and straw grass. Live roosters picked their way across the park. Little Havana is lousy with them.

Subsequent to our foiled plans, it took me several weeks of pestering in order to be granted an audience with the anthropologist. He was rightly suspicious of my prying, considering the long tradition of journalists looking for a quick hit about his field of study. But when we finally got together, he explained the mythology surrounding the ceiba tree. It has been considered an axis mundi among Caribbean, Mesoamerican, and African cultures for millennia: the branches are said to be in heaven, the roots are with the ancestors, and the trunk is with us. The ceiba at the Cuban Memorial Park has long been a place of heightened activity for santeros, a leafy, shadowy font of the supernatural.

Martin Tsang is the librarian of the university’s Cuban Heritage Collection, the largest collection of materials—artwork, journals, maps, correspondence, and rare manuscripts—pertaining to Cuban exile outside the island. He is also a Lukumí priest, his office’s walls and chunky black bookshelves decorated in small figurines and colorful lithographs of the orishas, which he pointed out and identified in a lilting British accent.

He bristled when I brought up the animal carcasses littered across the city as though they were gum wrappers. “It hurts me to see things like that,” he said. “We all become tarred. It doesn’t further useful discussion.” In his view, the outwardly gruesome display could be read as dilettantish, indicative of a person who didn’t understand the sense of reverence and intimacy and swiftness the ritual commands, someone who had a short-term goal in mind. “Every religion is made up of assholes and saints,” he said. The former was presented in short order in Miami. “The religion is not something that unites these different people. They are trying to access it in very different ways.”

He said that there would always be a class of people who performed the religion transactionally, which goes some way toward explaining its popularity among narcos and in the world of organized crime, or for anyone who’s run afoul of the law. Use of the religion in that way seemed mercenary and loudly impious, which had certain resonances in the spirit of Miami writ large—a great bluff of a city, built on false assurance and speculation. “It’s a very disposable culture in general,” Martin said. “It’s a landscape that is often used rather than revered or respected.”

Martin’s scholarly work has focused, at least in part, on the indentured Chinese workers in Cuba who were used by planters to supplement labor needs as the slave trade ebbed. Roughly one hundred and forty thousand were shipped to Cuba from 1847 to 1874; 99.96 percent were men, he said. They were highly skilled men of letters, doctors, and philosophers, and had no agricultural training. Esteban Montejo speaks at length about Africans working alongside these Chinese immigrants, who fused elements of Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism with orisha worship, finding common cause in the doctrines of filial piety, and ancestor and deity worship, conditioning yet another permutation of the Afro-Cuban religion. A Chinatown neighborhood developed in Havana; a few generations later, a Chinese neighborhood emerged within Miami’s Little Havana—an enclave within an enclave. It’s not uncommon to walk into a botánica and be greeted in Spanish by a person of Chinese descent.

Martin shared a story from when he was in his early twenties and he’d first found out about the orishas. He started a blog dedicated to his guardian, Inle, one of the lesser-known deities, which included the scant references he could find and some personal reflections on the subject. Years later he would discover that his blog was being cited by academics as though it were a primary source. “You’d think it was coming from an Afro-Cuban elder, but it was actually this Chinese-British kid,” he said, amused. Examinations of Yoruba culture tend to operate under this type of circular logic. “I’m interested in why some people claim what they practice is more authentic or more traditional,” he said. “It’s not often the case that the tradition remains unchanged for one hundred years, but these claims of authenticity are what people have to give value to what they practice.”

The Latin and North American communities of orisha worship are often discussed as inferior to what exists in Nigeria today. Philip Neimark’s business is predicated on this, and he is not alone. Martin took out his phone and began thumbing through the Instagram and Facebook accounts for babalawos in America and Nigeria who sold remote consultations and readings, as well as African soaps and trinkets, to unwitting clients. They advertised spells to return lost lovers, money spells, legal spells—all with the tenuous authority of salesmen who can barely dissemble their own motives.

To further the point, Martin recommended the work of his late mentor, J. D. Y. Peel, an anthropologist at the University of London and towering figure in the field of African studies, especially the region of southwest Nigeria. In his book Religious Encounter and the Making of the Yoruba, Peel argues that the fundamental concept of Yorubaland—that is, a historical nation in West Africa—is a spurious one, a colonial narrative invented by nineteenth-century Protestant missionaries. As Montejo illustrated, enslaved Africans were ascribed nationalities upon disembarking in Cuba and had no choice but to internalize them. A similar process occurred in Africa. Missionaries were the bearers of the European idea of nation-states. “The very ethnic category ‘Yoruba,’ in its modern connotation, was the product of missionary ‘invention,’” Peel writes.

Africans held oral traditions; there were no written accounts of culture or religious practice. This afforded the missionaries a unique opportunity to write the narrative of Africa as they saw it through journal entries, often written by African agents working for the missionaries, that were transmitted back to England. Peel presents no evidence that there was ever a collective cultural identity in Yorubaland, but just the opposite. The missionaries made history in that they seamlessly created the historical nation of Yoruba, a so-called ethnogenesis. “[T]he narratives of Christian conversion and inculturation, and of the formation of the Yoruba as a people have to be seen in terms of the various ‘grand narratives’ that are told to make intelligible the recent history of the world and Africa’s place within it, such as the rise of capitalism, European colonialism, modernization, globalization, and so on,” Peel explains.

I came to realize that if Martin was telling me anything, it was that he didn’t want to be painted an expert—that it was hard to say if such a thing existed. Those who projected expertise made targets of themselves, and had something to answer for. There was no tradition except that of storytelling and narration, whether it was coming from the mouths of elders or the mouths of charlatans. In Miami, it was critically important to differentiate. The city operates on the complete faith and self-evidence in self-mythology as a singular virtue, in both secular and religious circles. The freedom to create one’s own bible, drawing from the mystical reserves of Nigeria, or Congo, or Christianity—that type of personal liberty was the conceit of the New Age and new religious movements, and seems transgressive considering what enslaved Africans had to do to keep their fires burning. But, there’s a litmus test for weeding out unscrupulous priests and initiates: determining how well acquainted they are with their ancestors, both in their blood relatives and the lineage of their initiating priest. A phrase Martin often hears repeated is, “If you don’t know your ancestors who came before, how can you call upon them?”

High Chief Nathaniel Styles knows his ancestors. Some of them are buried in the sea islands of South Carolina. Others he can trace back to what he refers to as a “royal bloodline” of Yoruba priests. Styles speaks in a dulcet tone, with a touching inflection at the end of his sentences that gently punctuates his thoughts. He grew up in South Florida and runs a nonprofit in Miami called Osun’s Village, through which he has been promoting Yoruba culture to an American audience for three decades. He’s been visiting West Africa regularly since 1984 and currently leads pilgrimages, for people of all backgrounds, to the Sacred Grove of Osun-Osogbo in Nigeria. He calls himself a cultural and spiritual ambassador of the Yoruba kingdom, creating a link between West Africa and the people in the diaspora, a preservationist of the entire culture. Like Philip Neimark, he has been initiated into Ifá and Santería-Lukumí and can read the two hundred fifty-six Odu. Unlike Neimark, he comes from a long line of Yorubans.

It is because of colonialism that these religions were taken to the far corners of the Earth. Styles said that this will never be a totally palatable reason underlying its proliferation. Echoing Martin Tsang, he suggested that wherever one encounters a new strain, or personage who seems to appear out of thin air, it should inspire a modicum of skeptical inquiry. “What is happening now is that everyone on the internet is popping up to be an authority of this or that, whereas before, you were validated directly by your community, and it was controlled on a person-to-person basis,” he said. Regarding the westerners who have adopted Ifá—black, white, or Latin—he exuded a tempered graciousness. “They’ve played a significant role in the diaspora. Without interlopers, who knows if the awareness would indeed exist?”

For him, there’s no questioning the idea that all of the syncretic religions have evolved from the core tenets of Ifá, which is to say Africa, and those who still live there and maintain it command a special kind of deference. “You can’t say that, because it’s written, it’s more valid. The real validity is when it goes from mouth to ear,” Styles told me. “The whole point is that we must respect the source. Respect those who have been custodians of the ancient knowledge.”

The babalawos and Ifá houses he visits in Nigeria belong to lineages that have gone unbroken for generations. To this day, nothing is written down. All of the rituals, readings, parables, and exegesis are committed to memory. A point of contention for them is the documentation of their material by the educated class of Nigerians and western academics. Yoruba elders no longer view that knowledge as sacrosanct once it reaches the hands of non-initiates and novices.

Drawing of Oya by Alberto del Pozo, Orichas Collection. Donated by the Campilli family in honor of Carlos Campilli. Cuban Heritage Collection, University of Miami Libraries, Coral Gables, Florida

Drawing of Oya by Alberto del Pozo, Orichas Collection. Donated by the Campilli family in honor of Carlos Campilli. Cuban Heritage Collection, University of Miami Libraries, Coral Gables, Florida

Relations eventually began to sour between Felix and me, an outcome that was as unfortunate as it was inevitable. We lived too close. I was perhaps asking too much of him in sharing elements of his personal life. It was also true that he annoyed the bejesus out of me. The last time we spoke was in the early morning. The lid to his nganga was open, a warped cone of smoke rising out of it. I told him that there were a few more questions I wanted to ask, but he didn’t answer his phone. I tried to keep my distance after that, feeling remorse for observing someone who perhaps wasn’t aware he was being observed. But I rejected the idea that he was without agency. He knew that I could hear him.

So I continued to watch him through the blinds, his eyes fixed on the ground, tattooed legs trapped behind the banister like one of the prisoners in Plato’s cave. He almost never left his apartment. Every morning, stepping out on his balcony, he lit a cigarette and set it down in his ashtray. Then came an overture of coughs and hacks and loosening phlegm, followed by the clicking. “In occultism the mind groans under its own spell like someone in a nightmare, whose torment grows with the feeling that he is dreaming yet cannot wake up,” writes philosopher Theodor Adorno. Was this what we’d turn into, given the ability to author our own stories, spending our future in ecstatic pursuit of predicting and then rewriting it? Either his wishes, hopes, and dreams were being realized, or they were being forfeited.

I wanted to get away from the noise, but I had nowhere to go. This ended up being a good thing, as I was desperate in writing a story of a religion that was at once immeasurably old while still in its infancy. An unlikely synergy started to form between Felix and me. We were both mixing what raw materials we had. He was throwing coconut shells; I was pounding a keyboard. The noises they produced didn’t sound much different. I took comfort in the fact that everyone around me was content in writing their own parts: Philip and Vassa with their Sacred Gardens; Martin at the university; the babalawos on Instagram; Chief Styles on his pilgrimages; Felix on his balcony. Peel writes that narratives are the embodiment of discursive control, “since the narrator is free to decide how it will end.” But in this case there was no end, only a set of frayed beginnings.

The last time I visited the Sacred Gardens was in early December. After the first few cold snaps, the young pine trees along Route 17 had begun to bald and the oak leaves turned pale red. Dust clouds spun off the blacktop, and the thinning branches, the same ashen gray as the sky, twitched in the wind. I stopped by the Winn-Dixie in Crescent City, and the big news in the check-out line was that the fair was in town. The cashier asked me if I planned to attend. I said yes because I didn’t want to disappoint him. And then I asked if he had heard of the Sacred Gardens.

“Out in the woods, right?” he said. “No, I don’t know much about it.”

I wasn’t in town for the fair, but to watch a young man who had flown all the way from California be initiated into Ifá, “to have an orisha seated in his head,” as Vassa told me over the phone. The ceremony is typically closed to non-initiates, but she’d made an exception.

When I pulled up to the house, I saw Vassa and her pupil—a white man who had an Anglo birth name but was recently christened Esug Bayi—standing next to the Esu shrine. A clump of sage was burning in a copper bowl, sending a milky cloud of smoke ballooning into the air. Esug was cradling an oblong piece of meteorite in his arms, which was mostly a dull brown color but had small notches carved out that revealed iridescent pulses of life. A sprig of mint rested on the crown of his head. Around his neck were the black and red beads worn by Ifá initiates.

Vassa sat on a small wooden bench with her head resting in her hands and admired him. Esug had been corresponding with her for the past fifteen years. During his last reading, he’d asked Vassa if it was time for him to take the final plunge into initiation. The gods said yes. He flew here to stay for four days and paid the requisite $4,500 to make it official. He was instructed to bring with him old, dark, and heavily soiled clothes that symbolized his former life, and burn them in a fire.

He took a long pull from a bottle of rum, swished it around in his mouth, and spat it at the mound.

“Look at you,” Vassa said, in a whisper. “I’m so proud.”

“Vassa has become the good mom,” he said, beaming. “She’s shown me what it feels like to be loved.”

“It’s true,” she said. “People didn’t treat him how he deserved to be treated.”

He looked at me and nodded, lips pursed as though processing a difficult thought.

Vassa had prepared some lunch for us inside the house. Philip was sitting in his armchair, with his walker parked in front of him. While we ate, Vassa explained that her proposal for insurance coverage of PTSD treatment for military veterans was approved. They would be starting the program sometime next year; the eggplant had worked. After lunch, Philip became ornery and Vassa said she would need to get him home to rest. Esug and I helped her load their things in the car and watched them drive away.

Later that night the temperature dipped, so we piled split logs into a basin at the shrine of Shango behind the house. Esug doused it in lighter fluid. Most of the wood was still damp from a heavy rain earlier in the week and smoldered but never caught fire. We spent the evening silently rolling around logs with our feet and poking embers, which glowed metallic orange before slowly fading to black.

Esug told me a story about the time he was confronted by some Black Nationalists at a Santería workshop in Los Angeles. They told him that he should find his own religion and stop trying to steal theirs. “But it’s a modern world, and so many people practice religions that they aren’t ethnically tied to,” he said, shrugging. “The orishas choose you; you don’t choose them.”

The lake’s surface looked like wet ink. Wispy clouds hung low in the sky just above the jagged tree line, which circled the lake and drew a larger circle around us. There were supposed to be spirits out here, but they were strangers to me. I heard no drumming or chanting, not even a low hum. There were no sounds at all except two dogs barking at each other from different ends of the wood.

Esug said he didn’t hear anything either. I asked what his life would be like now, how he thought the initiation would change him.

“I’ve heard of something called an initiation crisis. You get pushed off balance, out-of-whack, confused,” he said. “But I don’t know what else to expect. I imagine things will be pretty intense for a while.”

He took a long, intent pause, staring at the coals. And then: “I might have to step back and ask myself, ‘Who am I?’”

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.