More Like African Music

By Melvin Gibbs

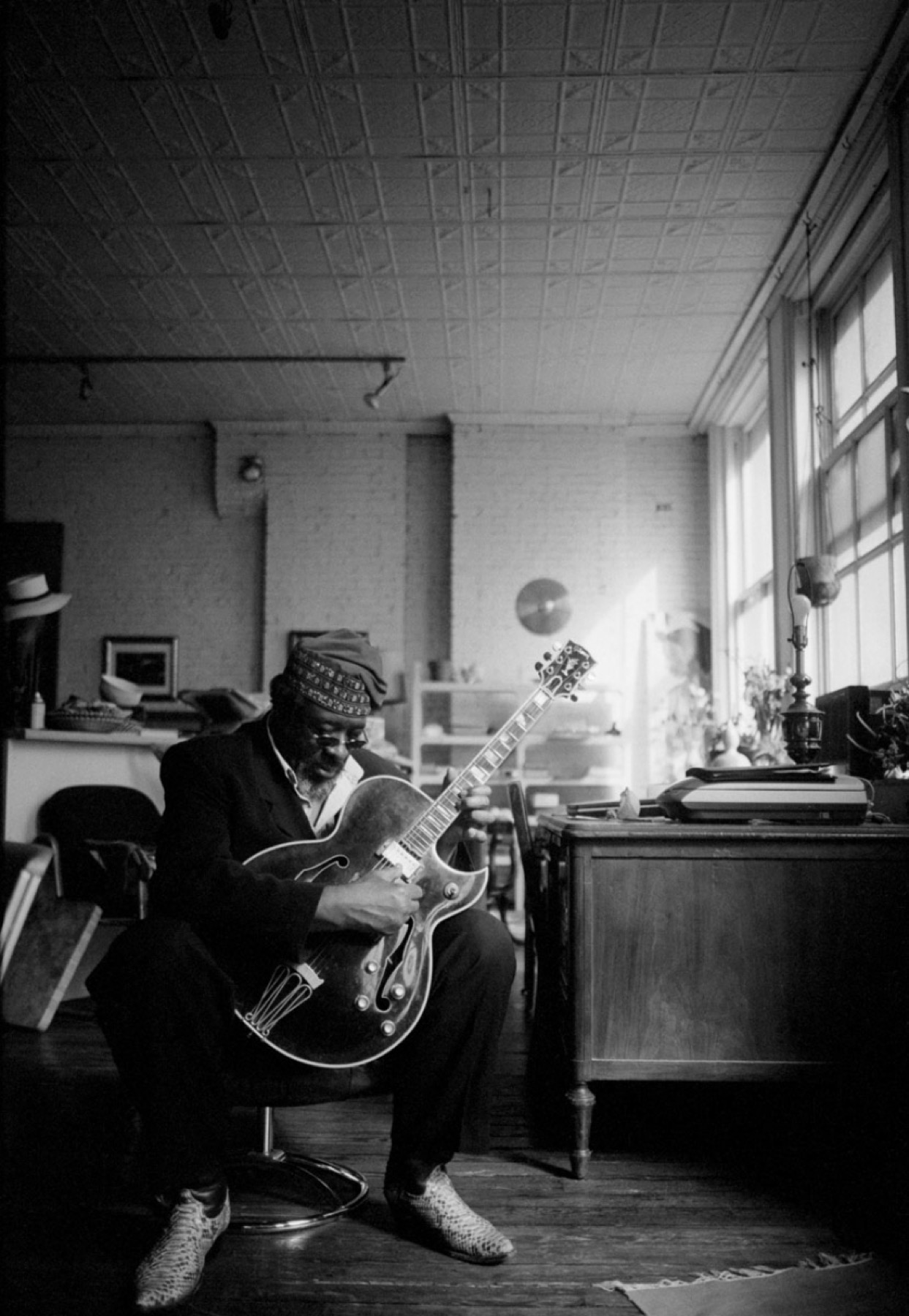

“James ‘Blood’ Ulmer in New York City” (2005), by Jeremy M. Lange

C

reative destruction is a constant in American music. Genres overtake genres, and popular forms, like clockwork, predictably become obsolete, overtaken by more culturally vital forms in a dance of birth, death, and renewal.

The music scene in New York City in the late seventies and early eighties was a veritable tsunami of simultaneous cultural birth, death, and renewal. Punk rock was renewing the bloated excess of rock & roll. Hip-hop, now the quintessential popular music worldwide, was being born in the ghettos of New York City. And free jazz, exemplified in New York by the DIY “loft jazz” scene, was tearing down walls and testing the boundaries of the form that would soon rebrand itself as “America’s classical music.”

In this milieu, but not of it, the singular guitarist/composer James “Blood” Ulmer made his mark. An embodiment of migration, both “Great” and forced, Blood was born in 1940 in St. Matthew’s, South Carolina, where his innovative music was initially nourished by his family’s gospel tradition. Following a path trod by many African Americans seeking a better life, as a young man he traveled to Detroit. There he played jazz at the same venue where George Clinton was workshopping what would become Parliament-Funkadelic. He then moved to New York, playing with shamanistic organist Larry Young before embracing Harmolodics, a term coined by the person most closely associated with the concept of creative destruction in jazz—Ornette Coleman. Ulmer’s first album, Tales Of Captain Black, produced by Coleman and released on his Artist House Records, is a canonical recording of the genre, a meeting of Texas and South Carolina in the House of Harmolodics.

When asked about Harmolodics, Blood said, “It’s bigger than what one person can say. Harmolodic is not a music it’s a way.” Calling it a “way”—a “Tao”—situates Harmolodics as a contemporary manifestation of the pure energy of innovation, cultural adaptation, and mutation that birthed music in America.

Blood’s Harmolodics puts “the cry” front and center. The cry is the aural exposition of the paradoxical mode of existence that forced the musical innovations made by Africans in America. Born of forced migration, it harkens to an Africa that exists only in the minds of its long-exiled American children. It is closely associated with the blues, but “the blues,” though a convenient signifier, is only one aspect of “the cry.” The totality of the cry is the totality of the emotional conundrum that lies at the bottom of the African-American experience. The Black Lives Matter movement is one example of the energy of “the cry” concretized. The joy in the faces of all the African Americans waiting on line to vote for Obama in 2008, many with their children in tow, was another. The dance of those dueling emotional vectors provides the truth that all the music of the Great Migration seeks to access.

“I’m trying to do music that doesn’t have anything to do with the piano,” Blood said. “More like African music.” To that end, he developed his own unique guitar tunings, which amplify his alternative resonance, allowing him to create a more-like-African dronescape that vibrates across the border separating sound and mood. When Blood altered the resonance pattern of his guitar to make it produce the sound he strove for, he—like John Lee Hooker and Son House before him—performed the sort of disruptive recombination that is at the heart of African-American innovation.

As a follower of a “way,” Blood is part of a tradition of those who built a culture that maintained an internal African logic though the external markers of that culture were taken away. South Carolina outlawed the drum, the quintessential marker of “Africaness,” in its attempt to prevent rebellion. But Africaness was maintained through kinesthetic re-coding and through the voice, through the “shout,” in both the African-American and European senses of the word. Like the blues, the shout is only the most convenient signifier—in this case for a mode of transcendence that exists as “ancestral” memory.

Blood is not bound by musical forms or formats. Traversing genres, Blood’s music ranges from his take on “Black Rock” exemplified by songs like his iconic (and once again timely) “Are You Glad to Be in America?,” to the proto-Americana of his bassless “Odyssey” trio, to his late-career rapprochement with the blues (navigated by Vernon Reid, leader of Living Colour) via his Memphis Blood project, to the haunting and harrowing solo guitar and vocal music captured on his Birthright album, and embracing the free/avant-garde of his Music Revelation Ensemble.

When asked what ties the different strands of his music together, Blood Ulmer, who will soon turn eighty years old, answering in light of a lifetime of making music, waxed aphoristic: “You don’t have to create a language. You just have to play the way you play. I don’t have a name for what I do.”

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.