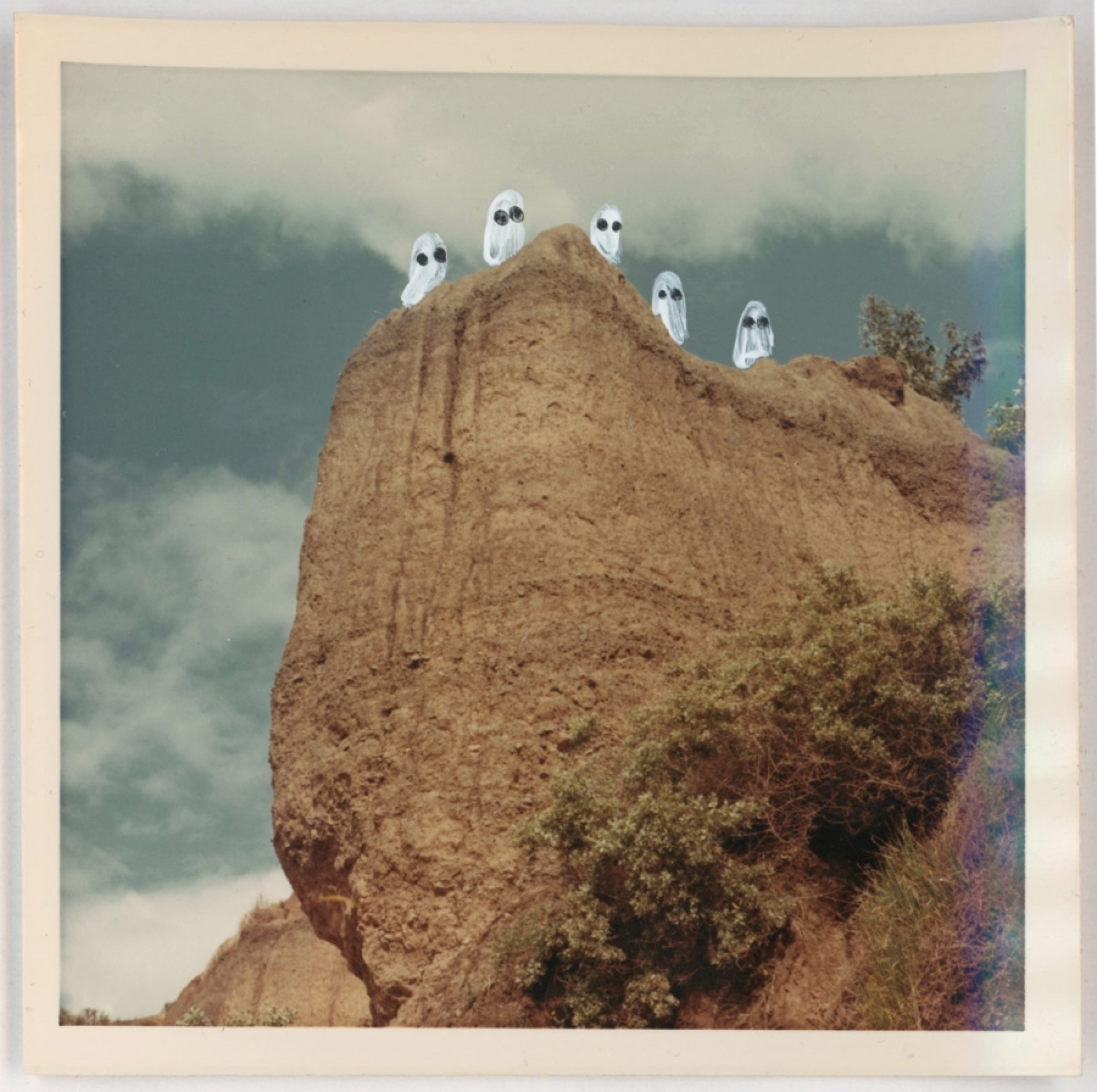

“Up on high,” by Angela Deane, from the series Ghost Photographs

Three Ghost Variations

By Kevin Brockmeier

A MOMENT, HOWEVER SMALL

A ghost with a poor sense of direction, distinguished among the company of ghosts for her amiability and her absentmindedness, took a wrong turn inside the house she was haunting, weaving left between the broom closet and the pretersensual ether, and found herself hundreds of miles away, on a busy street corner, where a light snow was dusting the air. Bewildered by the bustle and noise, she attempted to double back and return to the quiet rooms she considered home, but it was too late, for in the pandemonium of the crowd, she had forgotten the way. Such moments of disorientation were relatively familiar to her—if not exactly commonplace, then not exactly rare either—but always before, when her course led her astray, she would find herself within sight of another ghost, some kind soul who might point her to the door she was overlooking or the lane she had missed. Here among the living, barrowing themselves around inside their big heavy bodies, asking for help was not so easy.

She waited for someone to notice her. When no one did, she selected an old woman with an alarmed-looking dog cinched into her purse. “Excuse me,” the ghost with a poor sense of direction began, “I—” but though the dog barked and barked, the woman hobbled past her without so much as a glance. Next she tried a man in a business suit popping a breath mint into his mouth, then a skinny teenager with the rigid smile of someone trying to enthuse the chill from his body, and then a disheveled woman wearing a blue surgical mask. “You look like just the person to—” the ghost said, and, “I wonder if you might—” but they all ignored her, hurrying over the curb to wade into the torrent of cars. Not ten feet away, observing her efforts with a strange feeling of sleepy wonder, as if gazing into a fire, was a hot dog vendor. He had witnessed her appearance a few minutes earlier. Instantly he had known, from the way her pieces sifted together, that she was a ghost, though he had never seen a ghost before, nor indeed believed in them. Nervously he called her over to his cart. As soon as he understood her dilemma, he pointed out the orange utility numbers that were painted on the sidewalk. “You see that plus sign? You came out of the air a few feet above it, and maybe an inch or so to the left. I was watching.” The ghost thanked him with her usual aura of distracted kindness. Then, just like that, she was gone. The man stood watching the spot where she had been. Not long ago he had turned sixty, an age when people hunger for a moment, however small, that will justify the years they have spent and the years that still remain to them. In his bones he felt that his had just happened, on an ordinary street corner, in a snow so faint that it vanished before it touched the pavement.

THE WHIRL OF TIME

The ghost resided in a country full of clocks. Some of the clocks were trees, methodically adding rings to their trunks. Some of the clocks were breezes, marking a moment or two in the grass they ruffled or the curtains they churned. And some of the clocks were people, their hearts rhythmically pumping out the seconds. Behind the entire living world was the drum of time passing. Silently, from his gap in the air, the ghost listened as it rushed along. He had been a ghost for as long as he could remember, ever since an enormous pain he could barely recollect had ended his life in the mud and the rain. Since then, from his perspective, the years had gone by in a ceaseless barrage, replacing the generations just as swiftly as they created them. Children became parents and grew old and took to their beds, and then the beds were empty. Streets, fences, buildings, and monuments crumbled and melted back into the earth. Who could possibly keep track of it all? Who would try? Ghosts are meant to fix themselves to one particular house, meadow, or street corner—to select a place and haunt it. It is this tenacity of attention that keeps them from coasting through the centuries like herons over water. But this particular ghost had never developed the knack for standing still, so the material world meant less and less to him. Eventually, when the clocks of everything became too loud in his ears, he resolved to bring his flight to a stop. First he chose a dwelling to haunt, a small post-and-beam house on a hill beside a market square. The whirl of time took it down, though, before he could steady himself there. Next he chose a person to haunt: a young teacher instructing her first geometry students. He had hardly shown her his countenance, though, before she retired and was bones in a graveyard. Houses were too ephemeral, he decided. People were like raindrops. Finally he chose a stone to haunt, one of the oldest and most immovable in the city. Gradually, through an effort of will, he was able to move beneath its surface. A stone keeps its own time, and soon enough, haunting it, the ghost did, too. To his relief and surprise, the time he found himself sharing with the stone was less precipitate, more measured. From the crack in its side he watched the flicker of the seasons slow. The fields stopped boiling with flowers. The clouds began to cotton the sky. It was cool and quiet inside the stone. After a while, he ceased to hear the ticking of the trees, grass, breezes, and hearts. Whole days and nights went by when he forgot he was a ghost at all. He imagined he was only the large brown mass of granite resting imperturbably in the city park. The stone where the bugs no longer landed. The stone that the children no longer climbed.

MINNOWS

At first he failed to understand his predicament. To become a ghost upon dying was one thing, but to become a ghost centuries before you were born was something else entirely: a fate for which his imagination had simply not prepared him. There was the present, and on one side of it was the past, and on the other side of it was the future. Overhead was the sky, the sun, and a tissuey curve of moon. At the horizon a cliff peak stood ringed in white clouds. Time and space, he thought. What a hodgepodge. Luckily, the ghost was resourceful, with an intelligence that was, if not swift, then at least tenacious, digging and poking away at whatever questions the world offered up to him. So, by a kind of intuitive census, he took stock of his situation. This was how he saw it: the body to which he would one day belong was, for the moment, separated into billions of distantly arrayed molecules. Some of those molecules were enlisted in other animals, while some were jacketed inside fruits, grains, flowers, herbs, or vegetables. Most were washing around in various far-flung belts of the ocean. A few of course, by the law of percentages, were somewhere nearby, but from what the ghost could tell, they added up to no more than a freckle-on-an-arm’s-worth—not a body, or at least not much of one. Gathering them together, the ghost decided, would be futile. His only real option was to rally his patience and wait. Eventually the man who was destined to yield him up would be born and then die and the ghost could take his place. Very well then, he thought. He would set off into the centuries. Not far away a stream was trickling over a bed of shale and yellow clay. The sunlight was drawing bright tangles on the surface of the water, and a shoal of minnows was drawing bright tangles beneath it. From the long grass on the bank, the ghost extended the part of him that was practicing to be a hand. He wondered, as it pierced the surface, if the minnows would make a hole around it. All at once the light on the water seemed to impress itself inside him. Then, with the suddenness of a thought, he was gone. The universe had corrected its mistake. Six hundred and eighteen years would pass before the ghost returned, and eighty-one more before the body that contained him stopped functioning and he was set free. It would be male, that body, portly, slightly professorial but also slightly military, with back trouble and dry skin and the smell of soap hovering about it—the most intimate possession of an almost entirely ordinary man, one whose sole oddity, dating to his infancy, was the feeling that he had been alive much longer than he could have been, or than seemed possible.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.