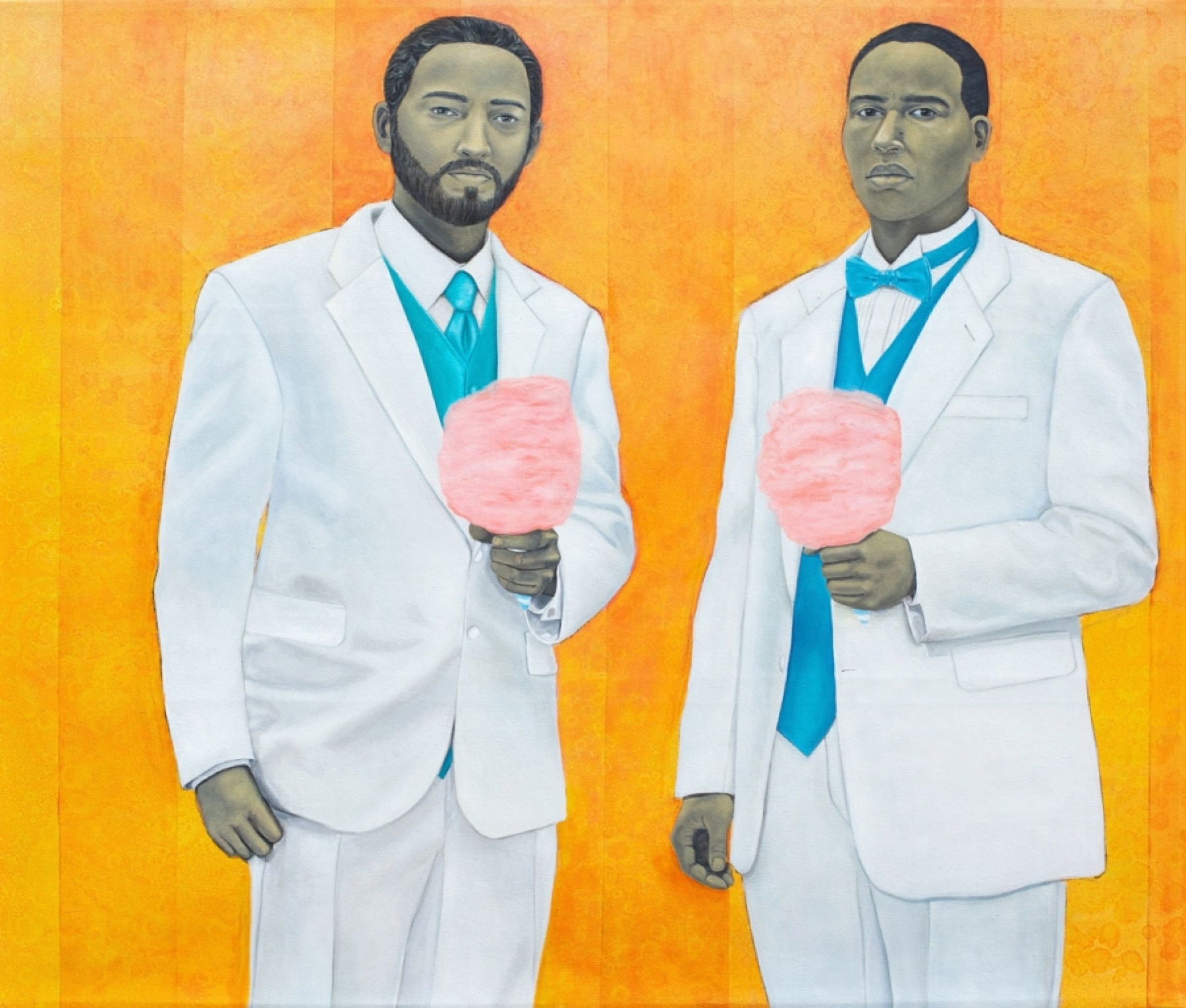

“High Yella Masterpiece: We Ain’t No Cotton Pickin’ Negroes” (2011), by Amy Sherald. Oil on canvas, 59 x 69 inches. Private collection, Baltimore, Maryland. Courtesy the artist and Monique Meloche Gallery, Chicago

That Kind of Money

By Abigail Covington

Liquid Pleasure’s ascent into wedding band superstardom

Kenny Mann understood before his bandmates did that Liquid Pleasure wasn’t going to make it onto Soul Train and get rich.

It was January of 1979 and Mann had recently arrived in Los Angeles, determined to become a star. Each night, he and a few other hungry hopefuls swung by the old Famous Amos factory to fill up on free day-old cookies before wandering over to the park behind the Comedy Store, crawling on top of their respective picnic tables, and attempting to sleep. In the morning, Mann rose quickly and scudded out to Sunset Boulevard, where he often bumped into bands that were “still washing cars during the day,” even after having performed on Soul Train’s famed burnt-orange stage the night before. “And they were better than my band, too!”

The reality check was disappointing, but Mann stuck it out until the day he spotted Ernest Borgnine cruising down Sunset in a Rolls-Royce with dingy, rotted-out tires. If the Cheshire Cat couldn’t afford a tune-up, how would Kenny Mann and Liquid Pleasure ever make it?

In 1980, Mann, then twenty-six, returned to Chapel Hill more or less for good. He quickly slipped back into the life he’d left behind—he was comfortable in the bucolic college town. People knew him as the son of “The Great Kenny Mann Sr.,” the beloved chef and manager of the Ram’s Head Rathskeller and creator of the restaurant’s famed lasagna, which had cured generations of UNC students’ hangovers. Kenny Mann Sr. believed in taking care of his employees, and the kindness he extended to them enriched his life and left an indelible impression on his son. Equally important to the development of Mann’s character was his mother’s sharp understanding of Chapel Hill’s “sophisticated racism.” From her, Mann learned to spot subtle but severe acts of discrimination. “The cruelest thing was to put African Americans in curriculum they knew would damn them to poverty,” Mann told me while recounting a long list of incidents of racism from his past. To this day his eyes still dart over his shoulder whenever he hears the Mamas and the Papas’ “Monday, Monday,” the song that was playing when a rock struck him in the head while he was riding his bike to school to receive his second-class education at Carrboro Elementary School.

Somewhere along the path to school, Mann usually ran into his cousin, Melvin Farrington. They both grew up near UNC’s main campus and where Mann was mischievous, Farrington was as serious as a textbook. “Melvin has never been a child,” Mann said, chuckling appreciatively before describing how whenever he and their mutual friend Leonard Hackney would pedal off on their bikes in search of hijinks, Farrington would instead be at home learning how to repair a carburetor. Farrington’s seriousness paired well with Mann’s personality. It was the dash of acid that keeps a rich dish from overwhelming the senses. And his obsession with instruments—what with all of their buttons and strings and dials and such—had good company in Hackney, who happily wasted countless afternoons stretched out on the front porch of his house trying to coax ever newer and stranger sounds out of his guitar. When I called Hackney and he came on the line, he interrupted a ringback tone that featured a heady blues guitar solo. “I just wanted to play . . . all somebody had to do was ask,” he said.

Hackney and Farrington, who played bass, wanted to make it as musicians. They dreamt of fame: the riches it would surely bring them and all the different kinds of freedom they could purchase once they were stars. Mann did, too, but Los Angeles had dimmed those lights and revealed to him just how cold and dark a stage could be when the spotlight wasn’t on you. He couldn’t tell Hackney and Farrington this just yet, though. They hadn’t been to Los Angeles. They were still operating under the assumption that if they practiced enough, they could be the next Temptations. Their goal was to make it on Soul Train, to play for their people, and above all else, to meet girls. They still had hope, and as Mann put it to me, “you can’t kill hope in a band.” Not wanting to crush anyone’s spirits (and perhaps still harboring his own hope despite the odds), Mann began writing songs on his keyboard for what would be Liquid Pleasure’s first and only LP—Kenny Mann with Liquid Pleasure—as soon as his plane touched back down in North Carolina and he reunited with his bandmates.

“Shake, shake, while you roller skate, HUNGH! Shake, shake, while you roller skate, HUNGH!” chants the band on the album’s closer, “Fun.” Mixed in behind them is a relentless conga-derived rhythm that’s been spiked with guitar licks from Hackney. Musically speaking, “Fun” positions Liquid Pleasure somewhere left of the Gap Band but just short of early Morris Day and the Time. It borrows the grunts from Edwin Starr’s counterculture anthem, “War,” but softens them out by pairing them with a fluttering soprano sax solo blown out by another North Carolina musician, Gino Faison. The more romantic side of Kenny Mann with Liquid Pleasure comes to life on mellow ballads like “Say What” and “If I Had My Way,” both of which remind the listener of the tender tones of Smokey Robinson during his A Quiet Storm era and the heart-on-the-sleeve lyrics of Teddy Pendergrass in his post–Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes days.

The album was a local hit. “From ’80 to ’81, Liquid Pleasure had the number-two record in our area,” Mann told me. But success always attracts opportunists, and the band’s national ambitions were derailed. First there were the pirates. “We were driving down the road and we’d see people selling copies of our album!” huffed Mann. Then there was the album’s producer. To Melvin Farrington’s ears, he had improperly mixed the music—the bass and drums are muted throughout the album, resulting in a consistent, tinny tone that afflicts each track. The producer had also scared away the national labels by demanding a payment of $30,000 to release his rights. Upon hearing these demands, the labels “backed up off us like we had the plague,” Farrington said with a sad laugh. “He really put the hole in the boat for us.”

The band was devastated, but Mann saw an opportunity in the loss. Liquid Pleasure’s corporate bookings had been growing thanks to the album’s success, which meant they had coins in their pockets. “We were negro rich,” said Mann. Still haunted by Ernest Borgnine’s beat-up ride, Mann began pivoting the band away from stardom and Soul Train and toward the more lucrative corporate gig market, knowing all the while he’d have to sell Farrington and Hackney on the transition. “They did not want to give up playing the black shows,” he said. “They knew girls there.” Going the corporate route meant having to sacrifice all of those things for a whiter way of life. Black clubs for country clubs, friends for fraternity boys. The music they all loved—like Cameo and the O’Jays—for something called beach music, which, according to Farrington, “We didn’t even know what it was.”

To get the other two on board, Mann had to make the change seem like it was in their best interests. That meant, as he explained, “the money had to be there.” All three members of Liquid Pleasure had children, and he pitched that the band could “make a living and raise our children doing what we loved.” That hooked them, and then the paychecks at the end of their first dozen or so country club gigs reeled them in. Reflecting on the fateful decision, Farrington said he remembered thinking, “If playing country clubs is what I have to do to not work a nine to five, I don’t have a problem with that.” Soul Train, as it turned out, was for suckers. Real success was financial freedom, no matter the cost.

In North Carolina in 1980, bands wanting to get booked for social and corporate gigs only had to impress one man: Ted Hall. Raised in Charlotte, Hall booked his first band, the Catalinas, to play the Myers Park High School prom after-party in 1959. “We called it ‘The Morning After the Night Before Party,’” said Hall in his slow but certain drawl. In 1960, Hall took his talents to NC State, where he quickly became the fraternities’ go-to guy when they needed to book a band. Soon enough, booking bands went from an easy way for Hall to make “a little extra liquor money” to a full-time job. By the time he signed Liquid Pleasure to an exclusive contract with his company, Hit Attractions, in 1980, Hall had created an enormous cottage industry in the Southeast: an entire economy in which song and dance bands like Liquid Pleasure supplied college fraternities’ demand for cheap entertainment. Cheap because there were so many bands to choose from, which meant Liquid Pleasure had to stand out.

What the band needed was a gimmick, something to separate themselves from all the other bands jockeying for the boys’ attention. The stakes were high. Kenny Mann viewed each fraternity brother as a potential source of renewable income—soon enough the young men would marry and need a wedding band. To secure all that future business, Liquid Pleasure’s gimmick needed to make a lasting impression. The band’s mentors, Doug Clark and the Hot Nuts, told dirty jokes between sets, delighting young men by insulting their dates. Mann and Liquid Pleasure decided instead that they would insult themselves.

It all started at a KA party at the University of Alabama. The brothers had hired Liquid Pleasure to be the entertainment for that evening’s party, but things weren’t going great. The audience seemed uptight. To loosen things up, Mann explained, the band let the brothers “come up and scream ‘nigger’ into the microphone.” It was a contest. “There’s no clean way I can say it,” Mann added. “We would let them come up and scream ‘nigger’ into the microphone.” Whoever screamed “nigger” the loudest, won.

The Monday after the KA party, Ted Hall phoned Kenny Mann with good news. Fraternities at UGA, UNC, Ole Miss, and Clemson all wanted to book Liquid Pleasure for the same night. “What the hell did you do at Alabama, Kenny?” Hall asked. Mann proceeded to tell his agent about the contest. Hall replied with a question from the fraternities. “Well, they want to know if it costs extra.”

“Yeah,” said Mann. “Tell them it costs five hundred dollars.”

In Sweet Soul Music, critic Peter Guralnick describes the fraternity parties that took place on college campuses across the Southeast in the early 1960s as “an important ingredient in the development of Southern soul.” “To Rufus Thomas, Percy Sledge, and countless others,” Guralnick writes, “the Southern fraternity circuit provided the best kind of gig: high-paying, dignified . . . and full of the most appreciative audiences that you could hope to encounter.”

Having been to a few Greek-life parties where bands were supposedly performing, I was baffled to discover that anybody, especially these titans of soul music, could have thought of fraternity audiences as appreciative—and I wasn’t alone in my dismay. Guralnick was equally surprised to discover that these bands not only enjoyed but actually preferred playing fraternity parties. “I expected Rufus Thomas, a sophisticated and intelligent man and a great friend, to tell me he felt taken advantage of,” Guralnick said to me over the phone this summer. “But instead, all I got from him was an appreciation for the opportunity provided to him.”

Kenny Mann felt differently. “I don’t know of a single black musician that really wanted to play the fraternity scene,” he said, after I briefed him on my discussion with Guralnick. Out on the fraternity circuit in the ’80s, Liquid Pleasure didn’t sense the same appreciation for the music that Solomon Burke and Rufus Thomas felt they received from the brothers in the ’60s. (Guralnick acknowledged that ’60s-era frat brothers’ enthusiasm for African-American music did not extend to support for social change and civil rights.)

If anything, Liquid Pleasure’s clients were fueled by a sense of nostalgia that was triggered by the release of National Lampoon’s Animal House in 1978. “That was their vision,” said Charles Bradshaw, a keyboardist who joined Liquid Pleasure in the early ’80s. The fraternities wanted an Otis Day and the Knights–type band, and Liquid Pleasure—having grown up under the tutelage of Doug Clark and the Hot Nuts (the band that Otis Day and the Knights was allegedly based on for Animal House)—fit the bill.

Quiet by nature, Leonard Hackney became animated when describing what he witnessed at fraternity parties at UVA, UNC, Alabama, UGA, Clemson, Ole Miss, and Dartmouth. “The guys would take a shot of liquor and dive down the stairs head first,” he hooted.

Having never been drinkers (or smokers) themselves, the members of Liquid Pleasure recalled the fraternity parties they performed at in almost uncomfortable detail. “We saw some crazy stuff,” agreed Farrington, elongating the a in “crazy.” And by that he meant, in no particular order: guys smashing beer bottles on the dance floor and against the walls, guys throwing up in the corner, guys throwing up onstage, guys getting offstage to go throw up in the corner and then getting back onstage, guys spilling beer everywhere (on Melvin’s bass; on Leonard’s guitar; on the drum set, the amps, and the microphone stands). Girls falling down. Girls falling down, then getting back up and falling down again. Guys rushing to get girls more drinks. Melvin’s wife, Gwendolyn Farrington, who became a member of Liquid Pleasure after performing in another band for a few years, remembered how the girls would lean on her, trying to steady themselves as they sing-slurred the words to “Respect” into the microphone. “I’d be like, ‘Don’t hold on to me! We’re both going to go down.’”

Ask each member of Liquid Pleasure how he or she felt about playing the fraternity gigs in the ’80s, and the answers will be contradictory. Farrington remembers moments of cross-cultural camaraderie, like playing basketball or crashing on couches with the frat brothers. Bradshaw recalls the gigs as merely part of the job. For Gwendolyn Farrington, they were a test of strength and bravery: “At the end of the night, you’d look around and say, ‘Okay, is everybody alright?’” Hackney gets a kick out of the irony: “They did some stupid stuff, but then . . . when they graduated they got jobs as doctors!” But for Anthony Springs, the suave, sensitive lead singer who joined the band a few years after seeing them perform at his junior high school in Durham in ’78, it was too much.

“I was becoming a negative force in the band because I really couldn’t tolerate the fraternity scene,” Springs told me over a round of iced teas at Raleigh’s North Hills Club. (He still performs with the band at weddings on a part-time basis.) Unprompted, he told me a disturbing story:

We were in Augusta, Georgia. This frat guy kept telling his girlfriend to get up onstage. And she was saying back to him, “I don’t want to. I don’t want to.” So he picked her up and put her on the stage. Well, she started having fun and got so happy that she ended up leaning over and kissing Leonard on the cheek. Then she jumped off the stage and went to put her arms around her boyfriend. That’s when he took both hands, shoved her in the chest so hard she fell to the floor, and screamed at her, “You kissed a nigger!”

Springs was exhausted by the fraternities thinking they could do whatever they wanted to the band just because they’d hired them. Problem was, letting fraternities do whatever they wanted was Liquid Pleasure’s thing. The band might have quit offering “nigger-calling” contests—Mann put a stop to that after about nine months because “the guys couldn’t stand it anymore”—but the frat brothers were still pouring beer on the band’s gear, hopping on stage at random, and manhandling the instruments whenever they felt inspired to test-drive those Lynyrd Skynyrd solos they’d been rehearsing in their dorm rooms. The long leash the band extended to the fraternities gave them an edge over more self-serious bands like R.E.M., who were also winding their way through the fraternity circuit at that time. And while Liquid Pleasure got a lot of mileage out of being the “fun” band, what ultimately gave them the gas to blow to the top of the circuit is what Mann refers to as the “Liquid Pleasure phenomenon.”

“I don’t even know if I like the music y’all play,” some fraternity brother told Kenny Mann in the early ’90s. “I just know whenever y’all are around, I get laid.” It may have been an expression of gratitude from a buzzed-up bro, but Mann heard dollar signs. Marketers of consumer products target women because they’re often the primary purchasers in their households. The same is true of weddings. Mann explained his strategy as though he were lecturing at the UNC Kenan-Flagler business school: “You really have to establish yourself with future brides. And the future brides are in the fraternity market.” Letting people scream racial epithets, being the “fun” band, fostering college romances. Mann put his bandmates through all of it for one reason: business.

These days, eighty percent of Liquid Pleasure’s weekend business comes from weddings. Hundreds of brides have told Mann they met their husbands at a Liquid Pleasure show. “I had a bride two weeks ago whose father and grandfather also had us at their weddings,” he boasts in a quivering voice, still shocked by his own success. Sitting in the driver’s seat of his jet-black Jeep Grand Cherokee, Mann explains that weddings are the fulcrum of the entertainment band industry. That’s what brings him here tonight, to North Hills Club in Raleigh, where I spoke with Anthony Springs earlier in the day. A lovely young couple is getting married, and Liquid Pleasure is playing the reception party.

I didn’t expect to be allowed to attend this wedding reception. I felt comfortable floating the request, though I didn’t think it would get very far. Certainly someone—Kenny, the bride, the bride’s mother, a loose-lipped, opinionated grandparent, someone, anyone?—would say no. And yet here I am, alone, at a wedding for a couple whose names I can’t recall, despite all the hacks I learned for remembering names in my cotillion classes. Colin? Was it Colin and Claire?

“I’m going to park the car,” Mann says, sensing my preoccupation. So I head inside to thank the couple before the bulk of the guests arrive. Upon noticing them by the buffet noticing me hunched behind the band’s gear, I walk over and extend my hand. They quickly shoo it away and wrap their arms around my waist, enveloping me in perfume and formalwear. “We love Liquid Pleasure!” squeals Marian, the bride. (I’d spied her name on an invitation discarded by the water station.) “It’s so awesome you’re doing this,” says her husband, Taylor. “These guys are the best!” They both possess an earnest politeness that, like the dogwood trees that line the entrance to the North Hills Club, is native to North Carolina and cannot thrive in harsher climates.

Soon after, within the space of two Four Tops covers and a lively rendition of “Uptown Funk” (punched up by an aggressive solo from the band’s drummer, Shedrick Williams), Liquid Pleasure goes from performing to an empty dance floor to a packed one. Anthony Springs and the other lead singers, brothers Troy and Ryan Corbin (they joined Liquid Pleasure four and two years ago, respectively), work like washing machines, spinning, twisting, and churning their way through the guests. Once the audience seems properly primed, Gwendolyn Farrington takes over. Farrington’s five-foot frame casts an unusually long shadow. In comparison to her quiet husband, Melvin, Gwen is outgoing, even audacious. Crowds adore her. That’s why it costs extra to book her. She’s the up-sell.

Before the audience sees Farrington, they hear her. “I need the bride up here!” she says from offstage. “Bring me the bride, y’all!” The bridesmaids usher Marian to the front of the stage as Gwen struts out from behind the speakers in a sequined black top. She quickly organizes the bridesmaids into a semi-circle behind the bride while Melvin and Leonard Hackney begin laying down the familiar foundation of “Proud Mary” on bass and guitar. The only difference between Gwendolyn Farrington and Tina Turner is four vertical inches. The swagger, the attitude—Gwen has it all. With their hands alternating between soaring in the air and perching on their hips, the eight young white women who now surround her follow her lead throughout the song, pursing their lips when she does and attempting to dip each time Gwen lets out a husky rolling on the riiiiivvah. Any effort to stick to the choreography is quickly abandoned as soon as the song picks up. Iiiiiiii leftagoodjobinthecity, she screams. The male guests fling their ties into the air as the women donkey-kick their heels off behind them. The entire ballroom full of people is now jumping up and down, spilling their chardonnay and Miller Lite all over themselves in the process. Kenny Mann flashes a smile at Gwen. She’s done her job. It’s a Liquid Pleasure party now.

During the cake-cutting ceremony and before Taylor and Marian’s sparkler send-off, I wave goodbye to the band, dash out the country club’s oversized oak doors, and dart across the asphalt left steamy from an earlier thunderstorm. Driving home, the cloying scent of damp honeysuckle and magnolia whips me back to 2006—the last time I saw Liquid Pleasure perform, at my cousin Billy’s wedding reception at a country club in Boston. I’d also seen them at Woodberry Forest School’s homecoming dance in 2003 and a few other social gatherings over the years at the Charlotte Country Club.

Growing up, I never considered what it must have felt like for Liquid Pleasure to perform inside all those white spaces. Why? Because I was young; because I am white; because I am privileged; because the city of Charlotte, like so many other cities, was specifically designed to ensure that white people didn’t have to live next to black people; because the civil rights unit of my third-grade American history class was suspiciously brief; because we could all stand to be a little more empathetic. Country clubs were my world, as natural to me as water is to a fish. Growing up, I thought the members of Liquid Pleasure were like sequined gods of Motown who enjoyed rearranging the old stubborn furniture in the stuffy rooms where they performed for various milestones in the life of a rich person: debutante balls, weddings, galas. I could see that they were remarkably good at convincing white people to loosen up, but I didn’t grasp that, for them, it was all an act—a job—and I was the audience. Not just for the band, but for the whole charade. The singing and dancing, the choreography, Mann’s jokes, the band’s banter—all of it was part of an expensive package sold to the highest bidder. Any personal cost to the musicians remained invisible to me until I finally asked Mann: “What was it like in there for y’all?”

“We’ve had some really rough times in country clubs,” he said. One time, at a country club on the coast of Florida, a manager spotted Liquid Pleasure strolling along the beach and called the cops because he thought they were a gang. Recently, at a wedding in Georgia, the manager of a country club fired a waiter on the spot for offering Mann a drink. On multiple occasions, they’ve had managers refuse to feed them, and it’s not uncommon for a country club member to inquire if a band member is lost when he or she is simply walking to the bathroom.

Bradshaw summed up the treatment Liquid Pleasure has received over the years in stark terms: “The people at the country clubs look at us, for lack of a better word, like the help.”

So why put up with all of it? I asked Mann.

“You gonna be mad, but what can you do?” he said. And because he knew I knew what he was going to say, he cut himself off before finishing the sentence: “We needed the money.”

As Liquid Pleasure became more in demand, they stood up for themselves by doing things like threatening to give up a gig if they weren’t given proper dressing rooms. In every case, tempers cooled, and over time their treatment improved. Having earned a gilded reputation among the East Coast elite, they now perform for some serious high-earners. Describing the typical Liquid Pleasure client, Tonya Williamson, a young woman from Greensboro who has performed with the band on a part-time basis for eight years, said, “The white people we perform for . . . they aren’t famous . . . but they are rich. These aren’t common white people.” Kenny Mann illustrated her point. He told me that he once overheard a coal manufacturer in New York City ask his secretary to order him a $175,000 pair of black pants.

“So, Donald Trump rich?” I asked.

“Yeah, in fact, Donald Trump Jr. is a client of mine!” Mann said with a laugh. (Yes, Liquid Pleasure has performed at Mar-a-Lago.) So is Laura Ingraham. Business is better than ever.

“You can’t mess up at any of these shows because most of these people, especially the rich people, they know everybody.” I was back in business school, this time with Leonard Hackney. “You mess up at this show and you could lose the next show.” There’s no room for error in Liquid Pleasure’s business plan, which has taken the band from dank basements of frat houses to private parties in the Hamptons. “The friends we made shooting basketball . . . it’s actually all coming back full circle now because [those guys] joined country clubs,” Melvin Farrington said. After signing with Ted Hall in 1980, the band rolled the dice and bet that soon enough, country clubs along the East Coast would be stuffed with Liquid Pleasure superfans. The payout was enormous.

“Liquid Pleasure was one of the first regional bands to break that ten-thousand-dollar barrier fifteen years ago,” exclaimed Larry Farber, a senior managing partner of East Coast Entertainment, the band’s booking agency. “Kenny Mann taught everyone in the industry there was a possibility of making that kind of money.” At one point, Mann owned a condo in the Dominican Republic, a condo in San Francisco, and a house in Chapel Hill. Melvin Farrington drives a BMW. Hackney collects motorcycles. By the mid ’90s, the three original members of Liquid Pleasure had achieved the financial security they sought and were in the top five percent of customer demand on East Coast Entertainment’s roster. Mann had pitched this life to his bandmates as a way to raise their children doing what they love. That is exactly what it has been.

“The band has a fabulous reputation,” said Scott Anderson, a banker and longtime Liquid Pleasure client from Charlotte. Anderson told me he did some financing for the band and stressed how rare of an act that was: “Lending money to bands is pretty unheard of because it’s so high risk.” He did it anyway because he trusted Kenny Mann and recognized his unusual knack for business. “I’d like to have a crack at his tax returns,” he joked, sort of. Larry Farber believes that Liquid Pleasure gave Mann the “ability to be seen on the same level as the aristocrats he was playing for” and pointed out that he has cultivated and maintained a lot of friendships with his clients. “People really care about Kenny Mann,” he said. And Kenny Mann cares for his band, who in turn, care for each other. At one point, Hackney, Mann, and Farrington loaned $30,000 to Anthony Springs on the sole condition that he use it to buy a house—which he did, and he lives in it presently. Tonya Williamson works full time for LabCorp, but the extra income she receives from her work with Liquid Pleasure has helped lift her into the upper middle class.

Being in Liquid Pleasure has also afforded its members, both old and new, things money can’t buy. Houses are essential, cars, a luxury; but community, fulfillment, friendship, and perspective? Those values are usually the first to go when someone’s primary goal is to make money. Or, rather, to get rich. Sniff around all you want, but no one in Liquid Pleasure reeks of greed. Their desire for money is practical and rooted in a realistic understanding of how much it costs to afford an upper-middle-class lifestyle if you weren’t born into one. Leonard Hackney and Melvin Farrington have always felt grateful for the opportunity to keep playing music—the thrill of entertaining a crowd remains. And the band members have relished numerous opportunities to travel. (Their trip to Aruba must’ve been a memorable one, because each musician brought it up at least once, on separate occasions.) They have performed in members-only resorts on private islands and in some of the most historically significant venues across the country. They have performed for every president since Jimmy Carter. They played for Michelle Obama (more than once) when she was a student at Princeton, and they met President Obama when he made a stop at UNC during the 2008 presidential campaign. “That was the highlight of my life,” proclaimed Melvin Farrington. Every time her friends come over, Farrington’s mom shows them a photo of the band with Obama. “That was a great high for everybody in the neighborhood,” he said.

Over the years, Farrington has made a pointed effort to stay connected to the Chapel Hill music scene from which he sprang. He still frequents local open mic nights and keeps his eyes open for new talent. He recruited three of the four women who perform with Liquid Pleasure part time: Charlieza Hill, Shavona Burton, and Jessica Graves (and is married to Gwen, the fourth). Farrington spotted Burton at an open mic night in Raleigh, and Graves was his waitress at Olive Garden. Both women now view Melvin and Gwen Farrington as mentors. The time and sincerity each member of Liquid Pleasure offers the others keeps the band together. Troy Corbin teared up when he described the impact Liquid Pleasure has had on his life. “They embrace my family,” he said. “They treat my wife like a queen and come to my son’s football games!” A phrase I heard a lot was: We take care of each other.

I don’t know if Kenny Mann has ever been in therapy, but I do know that he is exceedingly honest and possesses an uncommon sense of self-awareness. He willingly raises and struggles with difficult issues, like when he volunteered, “There’s an injustice to it but only eight percent of our income comes from African Americans,” and then followed up that insight with, “The number-one worst thing in this industry is racism.”

“Do you ever feel like you are disrespecting yourself?” I asked Mann after he recounted all the times he’s made jokes at the expense of himself to put white people at ease.

“Sometimes, but what clown doesn’t?”

Today, Liquid Pleasure is a member of the Chapel Hill–Carrboro Chamber of Commerce. From the mountaintop, you can see for miles and miles—except racism still lurks above the tree line. Despite everything Liquid Pleasure has been through and regardless of the success they’ve achieved, Farrington, Hackney, and Mann still face racism every day, and as Jessica Graves put it, “that’s just sad.” Graves is biracial and fair-skinned, and she told me she’s been treated better because of it. Larry Farber has known Mann for a long time and senses a sadness in him. “Music has created a lot of pain for Kenny,” he said. All those times he “had to bite his tongue,” as Farber puts it, have evolved into a pent-up frustration. “[We’re] still cotton pickers,” said Mann, in a crushing example of his tendency to self-reflect and analyze. “We’re just sophisticated cotton pickers now.”

Deep within Sweet Soul Music, Peter Guralnick writes about the many “sly assaults upon the system” Joe Tex and Solomon Burke pulled off during the time they spent entertaining all-white audiences in college towns across the Southeast. From performing songs that subtly celebrated the black experience to integrating a well-known hotel in Norfolk, Virginia, the singers employed the leverage they had as stars to seed progress in places where the civil rights movement often got stuck. Sometimes I got the sense that Kenny Mann believes being in Liquid Pleasure grants him a similar kind of power. “You wouldn’t know it, but they really are activists,” said Graves. Anthony Springs backed her up: “The band has helped so many people beyond what anyone realizes.”

Mann was drinking a Starbucks venti iced coffee when I spotted him at a picnic table on a hot August afternoon behind the temporary stage erected for Liquid Pleasure’s performance. His hands were clasped tightly around the sweating plastic cup. As we talked, he sat remarkably still but rotated his head in different directions, bringing his fastidious stare to every object in his line of sight without losing track of our conversation. That night, the band was playing a free show at North Hills, a shopping center with an outdoor pavilion comprised of upscale, stucco retail shops and restaurants. The whole place is connected by a series of well-paved roads dotted with crepe myrtles draped in twinkling white lights, their cotton-candy tops flashing like lightning bugs. Mann jumped right into a conversation about finances. “I’ll knock on wood, but it looks like 2019 is going to be the best year we’ve had since ’98,” he said. When I asked him what he thinks is responsible for the uptick in business, he responded with two words: Koch brothers. “As soon as Trump got in office, the Koch brothers loosened that capital and we started doing better.” The proof is in the bookings.

After the show, Mann was planning to drive straight through the night to D.C. He wanted to arrive early on Friday morning so he could visit the Embassy of Angola. “I want to pinpoint exactly where the Mbundus are from,” he said. Mann traces his ancestors back to the Mbundu, a tribe from Angola who are believed to have been among the very first enslaved people to arrive in America. Later in the evening, Liquid Pleasure would perform at a wedding in Virginia, then drive overnight back to Raleigh, catch a few hours of sleep, and head out for their Saturday night gig. In fifty-two years, Liquid Pleasure has never missed a single performance.

Mann has also been fielding calls from Laura Ingraham. She wants to book the band for a party at her house in November, but the date is taken. And besides, Liquid Pleasure was already scheduled to have a very busy November. For instance, on Election Day the band was planning to gas up their van at 6 a.m. and park it in the lot next to Mann’s office. “We’re going to give anybody who walks by a free ride to the polls,” he said. And he was looking into renting a handicap-accessible van to make sure elderly African Americans would be able to turn out in large numbers. “We’re always trying to help the community in quiet ways,” he said.

Quiet because Mann understands, just as Joe Tex and Solomon Burke did before him, that any display of overt activism could alienate Liquid Pleasure’s core audience. “If I have a voter registration drive, and a bunch of Black Lives Matter protesters come out to it . . . do you think my customers would be comfortable having me at their wedding?” Mann asked, before enumerating all the ways that doing so would negatively affect the band’s business. So, instead, Liquid Pleasure uses the money they earn to invest in and improve the segregated neighborhood they grew up in and increase opportunities for people of color to vote (“The only thing you can do is vote and try and create opportunities for people to vote,” Mann said). The stage isn’t their platform for change—their profit is. Kenny Mann knows Liquid Pleasure can’t turn down opportunities based on principle. And even if they could, they wouldn’t. “The need is so great right now,” Mann said as he shoved his arm into his yellow sequined jacket and got ready to greet the mostly white audience that awaited him. “We’ve got to keep making money.”

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.