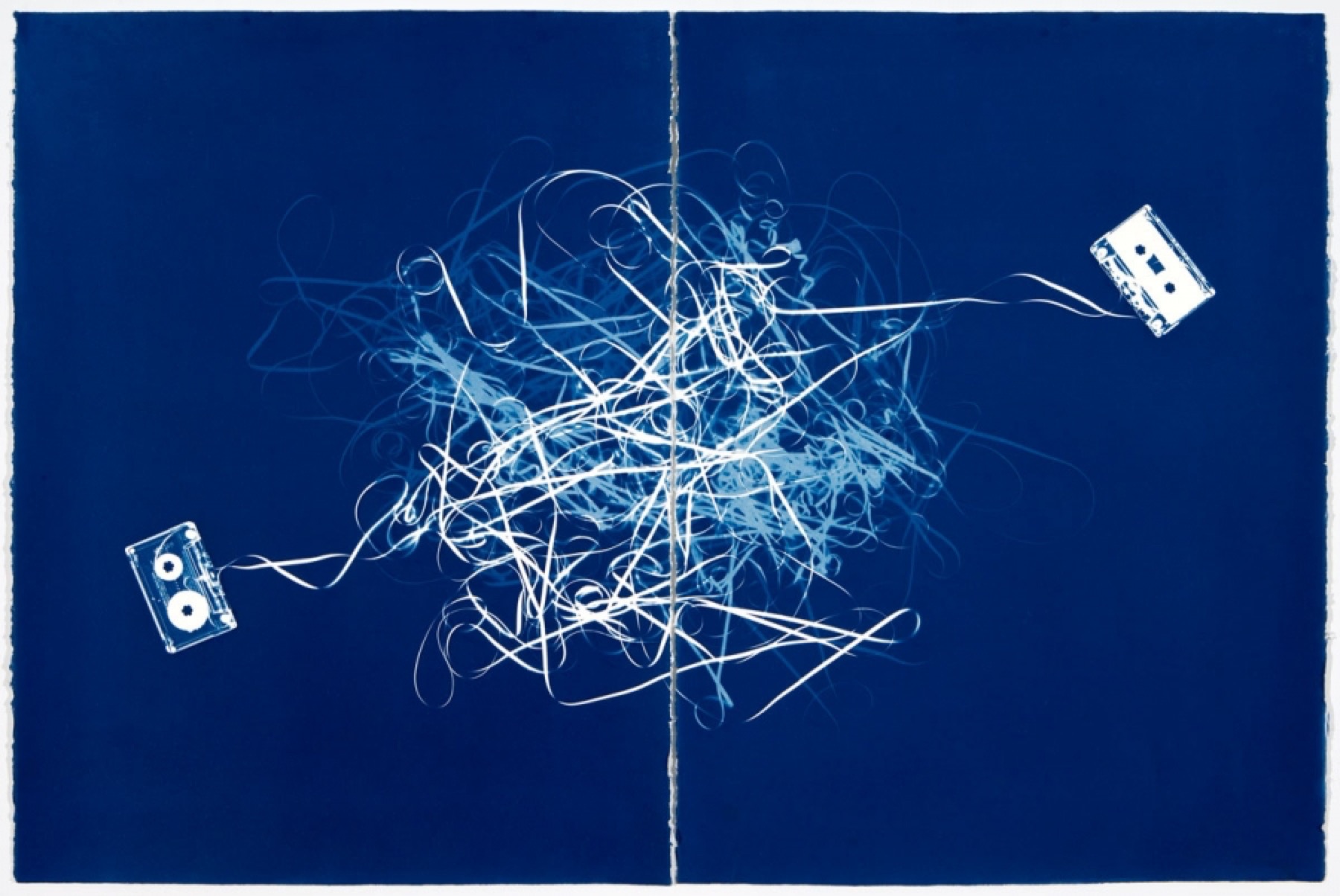

“Mashup (Two Cassettes Diptych)” (2008). © Christian Marclay. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York, and Graphicstudio. Photo by Will Lytch

I Remember the dB's

By Jonathan Lethem

(After Joe Brainard)

I remember the dB’s. I was eighteen. It was 1982. The band was still together.

I remember time and space were different then, and information moved incrementally through these media. Only a handful of things ever happened to everyone all at once—things like John Lennon’s murder, or Reagan’s election.

I remember I hadn’t heard of “Stamey” or “Holsapple” or “Mitch Easter” or “the Hoboken scene,” and I wouldn’t know the dB’s had anything to do with North Carolina or really any geographical specific for years. I remember I sort of thought every post-punk band that didn’t sing with British accents was from New York City, just because.

I remember I slightly later sorted out just enough of the basic facts: that the dB’s were a band fronted by two singer-songwriters, Chris Stamey and Peter Holsapple, and rounded out by drummer Will Rigby and bassist Gene Holder. Two guitars, bass, drums—the classic rock format, and Beatlesque with the two frontmen. That they’d played with Mitch Easter, famous for producing R.E.M., which gave them at least a nominal connection to the South. And that there was a Hoboken scene, bands who passed between Manhattan and that nearby New Jersey city, like the Feelies, and, later, Yo La Tengo. I learned these things, and for a while they were enough to call knowledge.

I remember my friend Joel Simon and I left Brooklyn for college. I went to college in Vermont and Joel went to college in western Massachusetts, and I could hitchhike between them pretty easily. The first time was freshman year, first semester, and Joel was already a DJ on the college station. He brought me into the studio to watch him do a show and he played the dB’s’ “Bad Reputation” as well as Human Sexual Response’s “Jackie Onassis.”

I remember I wanted both songs and he made me a cassette mixtape that included them both, and I took it back to Vermont.

I remember next that someone—my art-student friend Robert Ajar, maybe?—gave me a tape with Stands for deciBels on one side and Repercussion on the other side. The cassette was meticulously track-listed in tiny handwriting. I carried it with me and played it endlessly. The dB’s have managed to stack up many subsequent albums—(spoiler alert) both with and without Stamey, compilations and retrospectives, reunions, solo records, and I’ve relished many of these things—but it still seems to me that those two records are the real story, the imperishable contribution, the center of their accomplishment, that which the band was sent to earth to do. If all the rest vanished, they would be enough.

Tape cassettes! How we dubbed and dubbed, measuring albums to C60s and C90s, cramming extras onto the sides, enduring tape hiss, hand-decorating tiny folding inserts. Oh, the music download bandits of the internet had nothing on us! I probably never contributed a dime to the dB’s until I bought an LP of The Sound of Music (and even that I might have bought used).

I remember like it was yesterday the day in the sun on the lawn outside the off-campus house where I sat with my roommate Mark and smoked pot and sprawled on the grass listening to that dB’s tape, jangly worldly punky teenage pop, on a paint-spattered boom box running off D batteries.

I remember that one of the coolest, most seemingly indifferent and unattainably stylishly punked-out girls, who lived in that off-campus house, wandered over and saw us and said, “Oh, I get it, you’re those kind of brainy boys who listen to bands like the dB’s.” I remember how suddenly I saw myself whole in her gaze, with my torn jeans and Converse high-tops and bowling shirt and self-imposed irregular pineapple Chris Stameyesque haircut, getting high in the grass and maybe not so different from a dB in her eyes, and thinking at that moment, Maybe I have some nerdy allure of my own after all, damn.

I remember that by the end of that year a seemingly indifferent and unattainably stylishly punked-out girl—not that one, but another one—was my girlfriend, and the dB’s, along with Jonathan Richman, seemed to have provided the roadmap for a certain kind of self-amazement at how you could be a “boy” who’d become, in any sense, eligible to be somebody’s “boyfriend.”

Her name was Madi Horstman, and she led a band of her own, called Jolly Ramey.

I remember when Madi and I were back in New York City for the summer and she was in her mother’s apartment on the Upper West Side and I was home in Brooklyn, she called in a request on WFMU, and it was the dB’s’ “Amplifier,” and she dedicated it to me and then called me on the telephone to make sure I was listening.

I remember it was the first time anyone had dedicated a song to me on the radio and it was typical of Madi’s wry, dark temperament that it was a breakup song and I liked that. I remember that I bragged about it enough that Madi, in her hardboiled way, told me to get over it. We didn’t break up (yet).

After all these years it’s still the only time anyone’s dedicated a song to me on the radio.

I remember just two or three years later living in Berkeley and finally owning a dB’s record, The Sound of Music, and how far away from New York I felt, and how I felt betrayed by Stamey’s leaving the band, and how worldly and posthumous everything felt though it was only 1986 and I was twenty-two. In many ways the post-punk/college-radio/“indie-rock” era that the dB’s seemed to emblematize (though they would be forgotten behind R.E.M., the vastly famouser jangly band) was really just beginning, but everything felt commemorative to me already.

I remember out of a dogged, almost painful loyalty seeking out Chris Stamey solo records.

I remember seeking out records! I remember rumors of records, the difficulty of locating certain records or even confirming the existence of certain records. How we interrogated record-store clerks who displayed both taste and patience, how we excavated through zines, which themselves had to be located in the blurry column inches of a zine-guide called Factsheet Five, in order to find the names of the zines that might match our particular obsessions. Nobody younger than thirty can have any idea what it is to sense a universe of music out there beyond reach, beyond touch, or to wonder what a song sounded like for years before being allowed to hear it.

I remember my search landed on a Stamey EP called Instant Excitement. Six songs, including a cover of John Lennon’s “Instant Karma” and the ethereal and entrancing six-minute love ballad called “Something Came Over Me,” which included the lyrics “we were locked in a car going miles per hour, back from whence we came” and “we could see through the air like it was invisibly fine” and which became both the song I fell in love with my first wife Shelley to and my resolute proof that Stamey was my soul-twin, The Great Lost dB.

I remember that I needed to feel that Stamey (who leaned to off-kilter sulk-pop constructions), rather than Peter Holsapple (who leaned to chewy primary-color rave-ups), was the greater songwriter and singer, much as I’d felt it important to choose Lennon over McCartney, or, in the Australian band the Go-Betweens, I’d also chosen between the two frontmen, both singer-songwriters (Robert Forster over Grant McLennan). Something in me demanded that, to love a band with adequate intensity, I should feel this defiant preference.

I remember another part of me sensing the absurdity of the choice when I also knew that Holsapple—like McCartney! like McLennan!—was plainly responsible for so many of my favorite songs, songs that had shaped my life and gotten me through. “Bad Reputation,” for one. “Amplifier,” for another. And, even after Stamey had left, “A Spy in the House of Love,” and “Window on the World,” and “A Better Place.”

I remember feeling that despite these post-Stamey dB moments, the answer to the conundrum was that, like a kid with divorced parents, I preferred Stamey and Holsapple together, that they belonged together and answered something in the other, and pushed each other to greater heights, like those other native songwriter-pairs. This was maybe a romance even worse than the romance of one-over-the-other because it was more esoteric, because its truths could never be proven, and because it was sadder.

I remember being taken by my friend Will Amato in 1989 to see R.E.M. on the Green tour, at the Oakland Coliseum. A jangle-band had conquered the world, and we were all ambivalent and amazed. Will had complimentary tickets because he was writing about music for one of the East Bay weeklies then, or pretending to, and so we watched the whole show from good seats, the stadium-rock version of R.E.M. at its ascendant height, and we were also able to go backstage afterward and mingle shyly with the band and its entourage. Michael Stipe had to use an oxygen tank after the performance because he’d spent so much energy. And there was Holsapple, who’d been reduced to an extra-guitarist role—R.E.M. needed “more sound” to fill up all those stadiums—and I knew who he was but didn’t approach him.

All the events in the foregoing account occurred in the space of just seven years, though I was a high school kid in Brooklyn at the start and near to divorce in California at the end. Whole worlds enclosed and encompassed. All the Beatles records, from “Love Me Do” to “Get Back,” were released in a span of about the same length.

Yet unlike the Beatles, the dB’s didn’t have an “ending,” in which they fragmented into permanent solo entities, and into the afterlife of their reputation (and then, for Lennon and Harrison, the afterlife). Instead, the dB’s, always half under the radar to begin with, stay half on the radar. They’ve displayed an ongoingness more like life itself—more like my life. There are the post-Stamey records, the reunions, and the Stamey-Holsapple album-length acoustic collaboration Mavericks. The dB’s never almost always already didn’t break up.

I remember when Mavericks came out how I felt yes, this is it, this is what I want, these two together—feeling vindicated that the two songwriters still cared to work together, that they knew what it was worth, and doubly vindicated by how good the record was, especially (but not only) “I Want to Break Your Heart” and “She Was the One” (a rocker from Stamey and a dreamy ballad by Holsapple, as if they’d partly merged again, or traded places).

I remember when the internet came out and by then my walls were lined with rock-historical treatises and guidebooks and histories by Christgau and Legs McNeil and Simon Reynolds and Michael Azerrad, and by then I could tell you that despite “I Read New York Rocker” and Ork Records, the dB’s weren’t a New York band, not really, and they weren’t even part of the Hoboken scene, not exactly—they were traceable to North Carolina.

I remember that by a certain point I could explain to you who Mitch Easter was and who Sneakers were and how the lineages worked, and I also had spent time in North Carolina and it made sense to me—that grain of lackadaisical brokenheartedness in Stamey, especially, that seemed native to his turf, and so it made sense that they’d ended up back there.

And yet all of this knowledge, this knowingness, doesn’t hold a candle to my ill-informed certitude that Stands for deciBels and Repercussion were fountains of feeling, that they told me who I was and what my life might feel like to me if I listened to them carefully enough—and oh, those guitars! And oh, those harmonies!

I remember, not long ago, visiting North Carolina for a conference on the conjunction of writing and rock & roll, and meeting dB’s drummer Will Rigby, who was now married to an old friend of mine, an unattainably stylish rocker girl turned gregarious rocker English professor, named Florence Dore—it was Florence who’d organized the conference.

I remember that when I gave my presentation, Will and also Peter Holsapple were in the audience—half of the dB’s, sitting in chairs, watching me up onstage! (Well, I was featured on a panel alongside the legendary English guitarist Richard Thompson, and that might explain why they’d shown up.)

I remember that afterward I met Holsapple and it was warm and I told him what a fan I was and he acted like it mattered to him to hear it, but I still felt starstruck. I couldn’t reverse the polarity, because that is the relation of writers to rock stars, forever—and also of former nineteen-year-olds to bands they listened to when they were nineteen.

I remember that everyone told me that Chris Stamey visited the conference a few hours later, after I left, and it was almost better that way for me. Holsapple was the approachable one, the one I’d meet in an ordinary human encounter, under fluorescent light in a sea of professors, at a conference where I was a professor myself. Stamey was, for me, something else. My dreamy-voiced, elusive hero, the one who’d left the band, eluding me again, still only glimpsed out there in the constellation of my wishfulness. “Something came over me, here it comes again.”

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.