Stay Away from Places with Directions in Their Names

By David Wesley Williams

“How is he?”

“It ain’t a sore throat.”

“I didn’t think it was.”

“Well, it ain’t.”

Joe paused. He tightened his grip on the receiver. He stared at the dirt and gravel at his feet, as if his next words were there, spelled out in stones.

“Does he wanna see me?”

“Not that he’s said.”

“Well.”

“That all you got to say?”

“I’m coming to see him,” Joe said. “I aim to.”

“Don’t expect no parade,” Bob Jr. said. “Ain’t Fat Tuesday just on account of you coming home.”

He had not gotten far. A week of working his way home, hitching rides and walking, south through Illinois and Missouri, down into Arkansas and to the verge of Tennessee, but he seemed to have gotten himself stuck, just shy of the river. It was West Memphis, still.

He had turned the corner from the cinder-block bar out front of the dog track and made it half a block down the frontage road, and there came upon a tattoo parlor. Outside, there was a pay phone, maybe the last working public phone west of the Mississippi. Joe seemed to exist in a dusty present these days, or maybe West Memphis was just naturally that way, poor town. His brother had accepted the charges with a grunt that the operator took as a grudging yes. She gave it back in kind. She may well have been the last operator on earth.

“Where are you, then?”

“West Memphis.”

“Hellhole,” Bob Jr. said without pause. He said most everything without pause; what was there to think about? “Shit heap.”

“It’s in Arkansas,” Joe said, as if this were a mitigating circumstance for West Memphis being a hellhole and a shit heap, as if towns and cities couldn’t choose their states any more than people could their families. “You been here?”

“Nope. And I ain’t been to East St. Louis, neither.”

“Well.” Joe was casting about in his mind for something to say. He never quite knew what. He lacked cunning and had no touch with malice. He saw no need to damn a place just on the face of it; he figured there must be a flower blooming somewhere in West Memphis, though he had seen no sign of one, and that maybe East St. Louis had a park where children played tag-you’re-it together while old men read newspapers from benches and spoke of last night’s ballgame.

“You know what Daddy said?”

“Which time?” Joe asked.

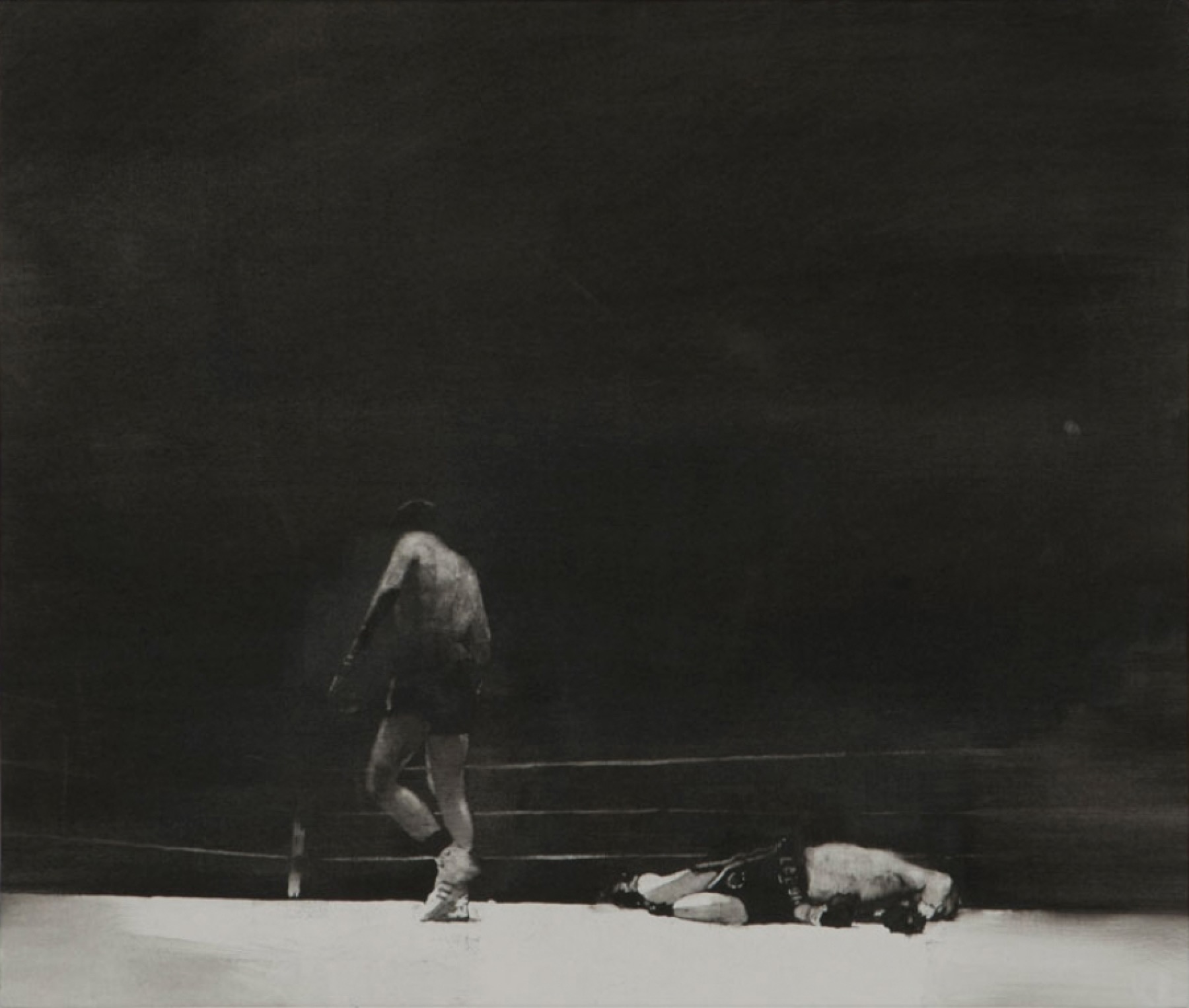

Bob Story Sr., the New Orleans bookie, said a good many things about the handful of topics that engaged him, about hard life and the lure of chance, about odds and angles, interest and the juice, and about women, of course, what cheats and creatures they were, and also about boxing. The latter was the only sport he respected; he once saw a man die in the ring and often regaled his boys with the story. In some renditions, there were exposed bones and in others there flowed blood enough to rival a minor Louisiana flood. The felled boxer usually had some final word to say, a guttural utterance you could hear from the rafters of the hushed hall. The other boxer would stand poised in a neutral corner, in a slight crouch, gloves waist high and hands taut inside them, as if he might be called upon to kill the poor sap some more.

Bob Sr. could abide football, but just barely. “Pads and leather,” he said, like he was talking about men dressing up as women. “Pads and leather and tight pants all shiny-like.” Bob Sr. was put off that so many of the game’s rules were meant to protect the quarterback, the pretty boy who minced about the pocket and heaved the football out of bounds rather than crack bones and bleed red like a proper man. He said the best thing about football was that fools bet their money on it.

Bob Jr. had PRAY TO GOD BUT PAY THE MAN tattooed across his shoulders, all caps in a gothic font, in tribute to the old man. The boys had been there when he spoke those words that first time, outside the Old U.S. Mint, on the edge of the Quarter, where hundreds of millions in coins had been produced. Bob Story loved a symbolic touch; it was, he thought, what separated the collections end of his business from outright thuggery.He loved an audience even more. And anyway, he said the boys were old enough to start learning the family trade. So they stood back and watched that night, as shadows fell thick as theater curtains, a velvet dark that begged silence for what was to come. But this was New Orleans, and so there was music playing, if only just—faint notes from a far-off street band, a honk and blare and thump-a thump-a. The gambler was a slightly built man in a Saints t-shirt, black with a glittering, gold fleur-de-lis. He was visibly shaking. A shove from their father and he was on his back. Then Bob Sr.’s shoe was on the man’s chest, centered on the fleur-de-lis. The man’s inevitable pleas and appeals went unheard; Bob Sr. seemed to be listening more to that far-off street band, as if trying to make out the tune. The music stopped and he inched that shoe onto the man’s throat. It was then the man beseeched his Good Lord. It’s what they all did, in the end. For Bob Story Sr. had no mercy, but maybe God would.

Bob Jr. watched as a budding boxer would a fight in a ring, fists clenched, as if his turn would come and he had best be ready. Joe turned away, but not so much that he couldn’t see the shadow of his father, twenty feet tall—drive-in movie screen tall; no, taller yet: yea high to the Old Mint itself, as if the great building were a marble bar on which he might rest his elbow and drink a Sazerac after finishing this business with the failed gambler who’d bet heavily on the hometown Saints to end last Sunday’s game somewhere other than on the seats of their shiny gold pants. Joe closed his eyes then, but didn’t think to cover his ears, and so heard his father say those words that became his trademark. The old man did, in fact, attempt to have them trademarked, but in the end settled, if it could be called that, for seeing them inked across the shoulders of his second-born and sole beloved son, his namesake and successor.

Late that night, in the small hours, the gambler was on the stoop of the Story house, a shotgun on East Fortune, with the money he owed, loose bills in a crumpled paper bag. So he was square with Bob Story, if not with his Good Lord. By dawn the NOPD had him for a grocery store break-in and a tourist mugging on Rampart.

Bob Jr.’s voice flared again, “I said, ‘You know what Daddy said?’”

“Which time?” Joe said again.

Joe remembered one time, his father going on for a small crowd in his back-room office about his love of boxing, all the bouts he’d seen. He told the one about the boxer dying, and in this telling the dead man rose just before the referee’s count reached ten. The other boxer bolted from that neutral corner and felled him again with a roundhouse right that shook the very arena; Bob Sr. said patrons fell from the rafters that night, and the lights, they blinked and flickered and then went black, and this time the boxer did, finally, die. One in the room, emboldened by the spirit of the story, and multiple snorts of whiskey, said, “Bob Story, man, you all the time talking about the fights. You ever take a punch?” Bob Sr. looked at the man with disgust or amusement—they were near about the same thing, with him—and said, “The fuck I wanna take a punch for?”

And Joe remembered one other time—

“He said, ‘Stay away from places with directions in their names,’” said Bob Jr., bringing his brother back to the conversation. “West Memphis. East St. Louis. South Side of anywhere. Said they’re all hellholes and shit heaps, good places to go if you got a hankering to get your ass shot up but won’t nobody do it for you back home.”

“They got a dog track here,” Joe said. “Greyhounds, you know. You should see those dogs run. They’re—” He about said beautiful.

“Guess you bet on one looked purty,” Bob Jr. said in his best mocking tone, “or had itself a funny name.”

Joe just sighed. He could take it. Mockery didn’t hurt as much as outright ridicule. He wanted to say no, he’d done the clear opposite of that. He’d bet on a sad-looking dog with a sorry-sounding name—Poor Boy, the seven dog, a ramshackle red fawn that went off at thirty to one. Poor Boy, like in the old blues song. Poor Boy, long way from home. It seemed almost wily, put that way. Cunning, even, except for the part about losing his last shred of money. The thought rose to the level of defiant pride in him. It was a small thing, but it was his.

“It wasn’t like that, Bob,” he said.

“Bet you lost your ass, all the same.”

“Well,” Joe said.

“Guess you’ll be wanting me to wire you some money. Which I ain’t.”

“I ain’t asking. I figure I can get home on my own. Just it’ll take a little longer now.”

“I’ll tell Daddy to hold off on his dying, on account of you coming but no time soon.”

“Tell him. Tell him I said—”

“What?” Bob Jr. said. And then, as if a weak moment had passed: “Look, I got to go. Family business ain’t gonna stop on account of the old man’s dying and it ain’t gonna lag on my watch. Mark that shit, son.”

“Bob?”

“Goddamn it, said I got to—” If he hung up now, it still would be the longest phone conversation they’d ever had. But it was like every other conversation they’d had—no conversation at all. It was Bob Jr., the younger by two years, throwing jabs and hooks for sport, or just to keep in practice for such time when someone was jabbing and hooking back, and Joe, not so much ducking and covering as he ought to have done, as instinct or common sense would dictate. No, just standing there and taking it all, like always.

But Bob Jr. didn’t hang up. There was some fun to be had, yet. He said, “Hey. Saw your old girlfriend last night.”

“Lily.”

“Ain’t what she calls herself now.”

“Where’d you see her?”

“At this bar over on—”

“Where?”

“She was dancing with—”

Joe thought of the sousaphone player who stole her away.

“—a pole.”

Bob Jr. laughed, and Joe took that time to steady himself. “That wasn’t her,” he said. “That wasn’t Lily.” He about said my Lily.

“I told you, she don’t go by that name now. It’s like she’s some other girl entirely, all growed up and gotten over having you as a boyfriend for about five minutes before some trombone player—”

Joe corrected him.

“Right, right. Trombone player wouldn’t have looked twice at that twig. Before some sousaphone player stole her away.” Bob Jr. laughed into the phone; it seemed about as much fun as the brute could have without someone pleading and bleeding at his feet.

Joe waited for him to stop, and then he just said, “Lily.” Solemnly, he said it, as if he had come upon her name in a litany of saints or perhaps martyrs.

“Cherry, I think’s what she calls herself now. No, wasn’t Cherry but something like that. Bad sign, son, when your girlfriend goes and names herself after—”

“She ain’t my—”

“She was there for about five minutes before that sousaphone player come along.”

“Well.”

“That all you can ever say? That’s all you’ve ever said. Well. You just standing there saying that word, like you ain’t tough enough to fight or smart enough to run.”

Joe looked at the dirt and gravel at his feet— the dirt was the color the gravel ought to have been and the gravel was no color at all—and then at the sidewalk a few steps away. Weeds had grown up through the cracks, made it to the light, and then died. Hard times in West Memphis, Arkansas, boys. Hard times, even for weeds.

“You ever see a sousaphone player who didn’t look like a sousaphone player? Hell, who didn’t look like his damn sousaphone?”

Joe sighed. He looked again at those dead weeds, bowed to the ground as if in prayer or mourning, one. There was silence, and then: “You ever wonder why they got married, Bob?”

“Your old girlfriend and him? Sousaphone player? I doubt it come to that. I reckon she moved on, quick like, to the rest of the brass section and then the full band, and then maybe some of the football team, if they’d have her. They probably wouldn’t of, back then, way I remember her—skinny little string-haired, stick thing with glasses on. But I bet they’d go her now, all grown, with her own pole and boots clean up to there and no glasses and that new name, whatever it is.”

“No, Bob. Our folks, our parents. Our mama and daddy. I mean—do you think she loved him? You think he loved her? Ever? Even for just a little bit?”

“Love,” Bob Jr. said, like it was seventy-second, with an asterisk, on a list of seventy-three reasons a man and a woman might wed.

“Well. I’m just wondering. I think about it some.”

“Daddy told me one time that he knocked her up and then married her. Just like that. Said if he knowed it was gonna be you he might not have done any of it, the knocking up or the marrying. He said he wanted to call you Bob Jr. but then he got a good look. Daddy said babies got to come out their mamas fighting, little fists balled and screaming bloody hell. Because they might as well face up to the mean-ass world right from the bell. He said they born knowing it. But Daddy said you just kind of laid there, sad and flimsy like. Said you didn’t seem to realize hands made fists—the one thing every baby but you seems to be born knowing. Said you ain’t learned it yet. So he let our mama call you what she wanted and he kept his name in his pocket, waiting to see if she could spit out some better specimen of boy, later on, which she did, is what he told me about all that shit.”

Most everything else had been spite and evil and sport, but Joe knew this was true. Still, he said, “He didn’t say that.”

“Damned sure did.”

“He never.”

Bob Jr. grunted his approval at this turn in the conversation. Finally, he thought, a fight from big brother, if only just a little bit of one. And he thought of the story their daddy told about the dead boxer who rose from the canvas only to be killed some more, the damned fool. And he thought of another story Daddy told, about a boxer so dumb-assed that he was offered a hundred dollars to take a dive and a thousand to die on the mat. He went for the big money. Sounded to Bob Jr. like some shit his big brother would fall for.

Joe Story stood with the receiver in his hand for some time after his brother hung up. He stood staring at it as if some other voice might utter a few words now—the voice of God or, God forbid, his dying father or maybe the last operator west of the Mississippi. But there was no sound at all, just the trucks out on the highway. They sounded like a thousand cries for mercy.

Joe hung up the phone, said to no one, to himself, Well, and then set out walking, toward the big river, the bridge to Memphis. Then south, toward home.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.