Many Singletons

By Danielle Chapman

War, ownership, and family ties in Tennessee

When I was not quite three years old, my father drowned off the coast of Okinawa. He and my mother were scuba diving with a neighbor, also a Marine stationed in Japan, when an earthquake hit, churning up the sea. The neighbor made it out, but my parents got stranded in the undertow, treading water, choking it back every time another wave crashed down. They gripped each other’s hands for a long while, until, during one of their underwater spells, his hand drifted out of hers. Miraculously, my mother managed to stay afloat until the SWAT helicopter woofed out of the clouds and rescued her. She has always credited her strong runner’s legs with keeping her alive—her legs and the Baptist hymns from her childhood, which flooded her body as she treaded, buoying her atop the waves.

That’s the last thing I remember before I remember Fairfield, Tennessee. One minute, I was watching the sky pearl to a weird, phosphorescent yellow as my babysitter seized me and tried to shield my eyes. The next, I was sitting on the lap of my father’s father, General Leonard Fielding Chapman Jr., the former Commandant of the Marine Corps, in his ancestral home, a broken-down Tennessee tavern built in 1790, where it had been forbidden to move the furniture since the Confederacy fell. I woke into History as if into a second childhood, and under the impression it was my own.

I could never wake up earlier than Papa, though. Well well well, he’d say in the low, teasing baritone that was his signature when I crept into the kitchen at 5:30 A.M. every morning of every summer. Good afternoon. Then we’d take our coffee cups, his a ceramic urn sealed with a Scottish falcon for “Leonard,” mine filled three-quarters of the way with cream, out onto the back porch to watch the sun come up. I knew that I was in the presence of an important man. He didn’t wish to disguise it entirely. Gravity hung on at the edges of his lean, handsome face, a newspaper tint, a residue of Washington. As the grown-ups said, he would be my father now.

One morning, when I was five or six, after the sun had burned up over the corn, Papa looked at me significantly and said, “Come sit on Papa’s lap. I’ll tell you a story.” It was the story of George Singleton, my great-great-grandfather’s slave, who saved my great-great-grandfather’s life and our family from ruin. I was not to interrupt.

Robert Singleton, Papa’s granddaddy, and “Uncle George” were boyhood friends, Papa began. They’d been born just a few months apart, and they grew up together, as country boys did back then—riding horses, catching frogs, playing practical jokes. No one paid any attention to the color of their skin, he said, until they turned eighteen, which was right around the time shots were fired at Harpers Ferry. Robert soon joined up with the Rebels, as just about all the boys in Middle Tennessee did. It was a pretty pitiful company; half the boys didn’t have boots and marched to Stones River barefoot.

Here, Papa stood up from his chair and led me through the tavern’s cavernous dining room, its kerosene lantern muzzed like a cataract, into the bedroom where Robert Singleton had slept as a boy and where his austere iron-frame single bed still stood. On the wall was an imposingly framed letter, written in old-timey script and mounted on yellow poster board. Papa lifted it off its hook. “You read it,” he said.

Ma, I would like to have George this winter if he wants to come and you can reasonably spare him. The Negroes are all gone from this company and I find it very hard to get my washing done. I have never done washing but I will have to try it this morning as tired as I am. If you conclude to send him Ma send him with Lieut. Scruggs’ boys [sic] return but you must not deprive yourself of his services if you need him. I send you 30 dols Ma and I will send you more when we draw and I expect that it will be soon. From your son. Bob.

I declaimed it as best I could. He tapped the glass with his index finger, hard at the tip as a wooden spoon. If he wants to come, he repeated. “Now you remember that, Dani, because that’s important,” he said. “Mm-hmm.” For a few seconds he continued to say mm-hmm, mm-hmm, as he did when he’d made a point but wasn’t quite finished agreeing with it. If I spoke before he’d finished mm-hmming, it would be considered interrupting.

Robert got his leg shot off at Stones River. The carnage was such that the Union soldiers named the woods the Slaughter Pen because they recalled the stockyards in Chicago. Robert would’ve died if it weren’t for George, who’d joined Robert in the camp shortly after receiving his letter. He ventured out among the corpses after the North declared victory, found Robert, and dragged him to the Union medic tent. “And if he hadn’ta done that,” Papa added with emphasis, “neither you or me would be sitting here right now.”

George then made his way back to Fairfield, about thirty miles, to “fetch” Robert’s mother, and together they raced the carriage back to Stones River, found Robert again, and convinced the medics to let him recuperate back at Fairfield. When Robert recovered, he’d have to report to the POW camp in Ohio, as was expected of injured Rebels who were given medical leave; and he did go, as a matter of honor. “But here’s where things get really interesting,” Papa said.

Once Robert was safe in Fairfield, George left to join the Union army. All the slaves were free to go once the North took Stones River, so George went off to fight. He served with the 17th U.S. Colored Infantry, was promoted from private to sergeant, and stayed until the end of the war. “But then, you know what he did?” Papa asked, the blue light in his eyes flickering magnetically. “He came back to Fairfield. His home. Right here.”

I looked around—at Robert’s iron bed, at the framed letter over the fireplace, at the cherry wardrobe where Sally Sehorn Singleton’s big-bosomed slips still hung, stiffly yellowed, on rusted hooks. Right here.

When George walked up to the gate, he found Fairfield completely devastated. The farm was untilled, and the women and livestock nearly starved. The Yankees hadn’t burned the house, but the Confederate greenbacks that Sally Singleton had squirreled away were worthless, and the women couldn’t buy so much as a bag of flour. So George took his back pay as a Union soldier, which was a considerable amount of money, and he bought a parcel of seed. He planted it, plowed it, and made a crop that fed everyone on the place, black and white, and he kept the farm going for a couple of years, until Robert got back. When Robert finally returned from the POW camp—he limped all the way from Ohio on his one leg—he found the farm up and running again, with George in charge. In gratitude, and in order to pay his debt, Robert helped George buy fifteen acres of land on Kellertown Road. George and his wife, Barbara, farmed that plot well into their old age and raised twelve children there.

“I met George Singleton myself,” Papa concluded. “I rode with him in his buggy many a time and listened to his stories about slavery days before the war and all that had happened in this country. I reckon he was one of the most interesting men I ever met, a true American. And he was from right here. Fairfield, Tennessee. Mm-hmm.”

I remember that Papa went very quiet then. Maybe it seemed to him that he’d said too much, or maybe he realized that I was too small to appreciate the gravity of what he’d told me. In any case, the house then took the story of George Singleton back as it took everything, into wardrobes and drawers and mirrors poxed with forget-me-nots of corrosion—to molder until History summoned it again.

Though it would be a long time before I heard the story of George Singleton again, I see now that the questions raised by Papa’s telling of it prickled me to such a degree that they became the irritants around which the oyster of my personality formed. Why did he confide it when no one else was there? If “no one had paid any attention to the color of their skin,” why was the story somehow entirely about the color of their skin? Why was my great-great-grandfather always referred to as “Robert Singleton, the Civil War veteran who lost his leg at Murfreesboro, then went on to become Clerk of the County Court” rather than “Robert Singleton, whose life was saved, twice, by the black man his family had enslaved”? Moreover, what did all of this say about the America Papa so revered?

These questions, as yet inarticulate, stayed stuck to me when we went back to Woodbridge, Virginia, where my mother and I lived during the school year, and which embodied the pop-culture idea of a capitalist, multicultural America much peddled in the 1980s. Our neighborhood, Occoquan Landing, was a townhouse complex nestled between I-95 and “historic Occoquan,” once a Native American fishing village, since candied into a craft town and crammed with gourmet cheeses and potpourri. Though within biking distance of several Revolutionary and Civil War sites, it was hard to see much history through the high pyracantha hedge that buffered us from Route 123, a 55-mph cut-through to the Lorton Maximum Security Prison. The neighborhood was about a third African American, as was Occoquan Elementary, and I was forever pestering my mother to explain the bewildering race relations that I observed there. Why did the recess aide startle when she saw me carrying around a black Cabbage Patch doll I’d picked up and cluck, “Don’t you want a white one, silly?” Why did the white kids and black kids play on opposite ends of the basketball court? Why were MacArthur and Kenya the only ones to ever get sent to the principal’s office? Why did the popular game of playground cut-downs always begin, “Your mama’s so black you must live in a coal mine”?

Unable to get answers that satisfied me, I eventually turned to my black friend David Smith, the little brother of Eric, “the bad kid on the bus.” Eric had once been suspended for telling his teacher to go screw herself, but David was clever, quiet, and circumspect, maybe because of the benign cyst, like a hearing aid fashioned out of flesh, perched behind his ear. As I’d soon learn, though, while David liked to climb trees with me and play MASH for hours on end, he didn’t like to chat about race. “That’s just how it is,” he’d say, peeved enough to make me shut up. Later, in about fifth grade, David became the first boy to ever tell me I was pretty, and I filled many a diary page exclaiming in purple capital letters about what “HOT SHIT” I’d be in if anyone found out I was “IN LOVE WITH A BLACK GUY.” Apparently, my first takeaway from my racial investigations was similar to that of ignominious white women from Mayella Ewell to Rachel Dolezal—if you can’t understand stories about race, make yourself the protagonist.

My most powerful memory of my early education is of watching the black-and-white reel of Bull Connor siccing his dogs on young, black, peaceful protesters, and of it dawning on me, with religious force, that my grandmother grew up in Selma—a debutante, a member of “polite” white society, and one of the last living exemplars of the “Southern white womanhood” that the Klan had invented itself to defend. My horror at the crimes committed by white people, including almost certainly my own family, was visceral. Yet, when it came to doing something about it (the advice that Papa gave me whenever I griped, with adolescent ferocity, about our nation’s ills), I was baffled. What could one do about a situation that no one I knew would even talk about? Eventually, I did what everyone in Generation X did: I dodged.

In high school, my boyfriend was an aspiring drum & bass DJ whose parents were South Vietnamese refugees. If we realized that our relationship could never have occurred if not for our parents’ late military alliance in a failed war, we thought it would be “wack” to mention it. We spent our weekends sneaking out to raves in cities up and down the East Coast, joining in dance circles with black and brown and gay friends, holding hands while belting “We Are Family” by Sister Sledge. Then, in the car on the way home, coming down from our utopias, we listened to hip-hop—Black Sheep and Das EFX—and drove “laid back” in a “gangsta lean.” We felt no compunction about our acts of cultural appropriation (and no one called it that back then), though we did blush if a black person drove by and laughed at us.

By the time I headed off to college at NYU, I’d become a full-fledged, wannabe hip-hop head. I wore baggy jeans, Nautica shirts, and a Polo cap turned ten degrees to the right, as well as, it must be admitted, gold door-knocker earrings. Though I shared a dorm room with four other girls in the already gentrified East Village (our grimy windows looked across the street into the supermodel Cindy Crawford’s loft), I wanted nothing more than to be down with the downtown hip-hop scene. I had a friend who knew Bobbito from Hot 97’s “Stretch Armstrong and Bobbito Show,” and she got us into the clubs. Back in the dorm, I pored over the mixtapes she gave me, reeducating myself with views from “the other America”—and, alas, wrote furiously in my own rhyme book under the moniker that I imagined would make me famous as the first white female rapper to come out of the New York underground: The Wise Cracker.

It wasn’t until I flew down to visit Papa in the summer and found myself in Middle Tennessee again, looking over the pasture at the industrial chrome trailer where Jim Wesley raised bacon, that I recognized the absurdity of my desire to “be black.” It was on that very rise in the land that George Singleton, the man who had saved my family twice and without whom I would not be alive, was born—in a slave cabin my ancestors had built and fought a war to keep him in. What relation did his story bear to the fool I was playing?

Sooner than I could have imagined, this question became more than rhetorical. For, as it turned out, while Papa’s version of the story of George Singleton was being passed down to me, a nearly identical narrative had been making its way to the black Singleton descendants—a sprawling network of actual people whose lives were tied up, with great specificity, with my own. All that time that I’d been tearing up dance floors across the tri-state area with my two left feet, humiliating myself at open mics, and thrashing around in the unceasing urge to forge an identity that would free me from my whiteness, there was a large African-American family, down in Tennessee, looking for my family.

The first reunion of the black and white Singleton descendants took place in 1998. Mike Davis, George Singleton’s great-great-grandson, who was then a D.C.- area cop, had tracked Papa down, encouraged by his mother, Ella, who recalled how General Chapman had always stopped by to give her Aunt Odie Kay a potted plant when he was in Tennessee. Papa accepted Mike’s invitation to one of their reunions in the D.C. suburbs and spent the afternoon sitting under an oak tree, sharing admiring stories about “Uncle George, as he was called back then.” Mike told me that it was like a celebrity had showed up when Papa walked into the reunion. Some people had flown to D.C. from across the country to meet him, not because he had been a big man in Washington, or not just that, but because he had actually known their patriarch, a man no one else there was old enough to have met in person.

The following year Papa invited everyone to Fairfield, and the gathering was a grand success, with everyone sharing stories and food, George’s descendants fascinated as they toured the house and witnessed all of the perilously preserved history. There were no tears, no lamentations over the tragedy of slavery, no accusations, Papa told me; in fact, he said, George’s folks seemed to agree that our slavery story had “turned out well.” It was the story of George Singleton that allowed it, he said, and it was the success and classiness of George’s descendants that proved it.

I claimed I couldn’t make that inaugural reunion because of work, though the real reason was embarrassment. I cringed at Papa’s narrative gloss, not without a touch of grandiose concern at how this unforeseen development might compromise my credentials as a race-conscious liberal. By then, I’d graduated from NYU and was working for New York City’s children’s services department, doing programming for youth in foster care, where ninety-seven percent of the kids were black or Latino. I was thoroughly exalted and exhausted by the intensity of my job, constantly taking on new responsibilities for which I was almost criminally unprepared. Unbeknownst to my conscientious coworkers, my fervor for service was fueled by my devastating recent breakup with a young man very similar in background to, and not much older than, the teenagers I was working with. I had my own reasons to cringe. The African-American descendants, on the other hand, appeared to have been pleased by the gathering. In fact, a few weeks after the first reunion, they’d already started planning the next one.

By the time the Singleton-McMahon Reunion rolled around the following year, it seemed pompous to boycott, so I scheduled my visit to coincide with theirs. The morning of the big event, as I milled around, watching the side yard fill up with Ford pickup trucks and Chevrolet sedans, plus Maurice Pepper’s convertible Mercedes, observing the middle-aged African-American couples moseying out of their cars, I grew jittery, realizing that my Northern views about Southern race relations were about to be disrupted by real people. Though maybe what I really feared was that the idyll of my childhood summers was about to change. Here was the yard through which I’d chased fireflies through the dusk; where I’d performed terrible dance routines to Whitney Houston in the “punk” neon crop top and pleather skirt I’d gotten for my half-birthday. Until now, Fairfield, whatever its secrets were, had been mine.

My contemporary on the African-American side was Tamekia McMahon, who’d recently enrolled in a master’s program in inner-city studies in Chicago. Everyone was waiting for us to meet. Elwood McMahon, George Singleton’s great-grandson and Tamekia’s uncle, had been, and always would be, the first to arrive. A slow-drawling, retired truck mechanic, Elwood was the single living brother of his eleven siblings, and with his encyclopedic knowledge of all things Middle Tennessee, proudly proclaimed his ability to outtalk all of his sisters. He leaned back in his porch chair and every so often interrupted his own musings to announce, “Tamekia said she was coming. She’s gonna be here.” Papa kept reminding me that Tamekia was pursuing her degree in history—as he’d always hoped I would.

I recall meeting Tamekia late in the morning, the scene extracted from the ordinary and plaited into a pane of light. She was pretty and much more citified than anyone else—slender and sloe-eyed and blemishless, not a hint of makeup, her dreadlocks immaculately cylindrical. She wore a white t-shirt, jeans, and sandals, and a simple leather purse, its strap across her chest, that she’d brought back from a recent trip to Ghana. “Everybody’s watching us. We better have something to talk about,” she said, raising her forehead at me.

I laughed too hard, knowing that, given the chance, I could talk to Tamekia forever. Yet, everything I tried to say to her, every bit of me that I tried to package up in words that I thought might resonate, puffed into the air—the air produced by the chestnut and the beau d’arc, trees my ancestors had likely instructed her ancestors to plant—then whined away like a clown balloon. Tamekia looked at me plainly. I don’t know if she saw the confusion fumbling through me in that moment, but I do remember that after I blubbered whatever I blubbered, she stood there silently for a good long time. When she finally spoke, she said, “I’m fixing to walk up to the cemetery to visit my grandmother’s grave.” Then she added, a bit reluctantly, “You want to come with me?”

As a child, when people found out that I was fatherless, or, worse, discovered that my father had “died in a scuba diving accident in Okinawa,” my habit was to halt the precipitous falling of their faces with a preemptive, “It’s okay. I hardly knew him. Besides, my grandfather is like a father to me now.” This statement pleased my military family, who lived by maxims like grin and bear it, but my denial had some unintended consequences, one of which was my fixation on other people’s sufferings, particularly those of black people in America. It never occurred to me that my gaze, so strenuously empathetic, might have been born of narcissism—that I might have been looking to others’ pain in search of an image that would describe my own. But, if I’d cared to investigate, one clue might have been that I had always made Papa—the powerful, white, American, male stoic next to me in the car—my singular audience and the whetstone against which I sharpened my race-conscious self.

As a teenager, I blamed institutional racism (i.e., in my mind, Papa) for the rutted row houses of Southeast D.C. that we passed on the way to Washington Redskins games; he’d harrumph, tell me to read William Raspberry on “personal responsibility,” and stare straight ahead through his yellow aviator driving glasses. I dared him to justify the fact that the Marine stewards at the Commandant’s House were still all black. “Those are good jobs, Dani,” he said, with maddening calm. “Marines compete to get those posts.” Once I started really reading—Race Matters by Cornel West was the first real jolt—my views intensified, and when Papa took me out to dinner, conversation almost always turned into a debate. He tried to keep it light, and, when the shouting was over, he’d rib me by walking over to surrounding tables and telling the patrons who’d been unfortunate enough to sit next to us, “I won,” with a confident wink. Yet, more than once, things ended with me bawling over racial injustice, and him scolding, “You’ll never win an argument if you get hysterical.” While the connection with George Singleton’s descendants had presented a new complication to our relationship, I had yet to reflect on how it would change it.

Then Papa died. Less than a year after I walked with Tamekia to see her grandmother’s grave, a simple stone laid flat in the sumac shade and adorned with trinkets, a stone Tamekia seemed to know as well as I knew any human, Papa was buried in Arlington National Cemetery, with the entire Marine Corps band playing “Taps,” a eulogy from the Commandant, a procession of seven hundred mourners including the Secretary of Defense and the Catholic Archbishop of D.C., and a twenty-one-gun salute. Each one of these honors, despite the great precision with which Papa had ordered them in his will, intensified my sense of error until, during the presentation—to me—of the American flag that had lain over his casket, the spectacle engraved itself into my soul as a bitter mistake. I’d been there for the surgery, when they’d successfully scraped off the cancer, but Papa had caught pneumonia while recovering. More than once the nurse had caught him furiously yanking the ventilator cord out of the wall. “I’m ready to go,” he’d spit. It was hard not to notice the difference between this deathbed behavior and that of Stonewall Jackson, whose last words (supposedly uttered while dying of a gunshot wound at the Battle of Chancellorsville) Papa had often quoted: “Let us cross over the river and rest under the shade of the trees.”

It’s a blessing, family members and friends said; he went out, at eighty-six, in sound mind and excellent health. That was how he would have wanted to be remembered. Maybe. But Papa, who’d been a father to me, was gone. The Marine Corps sent a formal party of bereavement officers, as for men killed in combat. Nana’s old friends, most of whom I hadn’t seen since she’d died six years earlier, served strong coffee and thick cream in the porcelain she’d brought back from Japan. The creampuff pointillism of her sitting room—brocaded settees, petit-point pillows and stools, excess of portraiture and picture frames—acquired the elegance to which her whole life with him had aspired even as the officers’ consolations skidded over my ears.

On the third day, Papa vanished completely. The silence around his house roared. In his Alexandria attic, where I’d once sat on his lap, soldering the wires to the circuits of his Heathkit TVs, I now sat on the volcano-colored carpet, dumbfounded. At some point I opened my father’s footlocker, which Papa had given me when I graduated from college—my father’s letter jacket, diplomas, and combat medals heaving out the mentholated anonymity of two decades in the dark. When Papa had presented it, I’d dismissed the gesture as morbid and given it only the most cursory once-over. Now, I sobbed in rage, realizing as if for the first time the absolute specificity of the life I’d been cheated of—my father’s life, in this box, which I knew would never be contained so well again.

A few months later, I met up with Tamekia in Chicago. The simplicity of her appearance—no jacket, no bags—distinguished her from the squawking crowd revolving through the glass from Michigan Avenue into Water Tower Place, that atrium of ascending fountains timed to spit symmetrical fireworks of water alongside the escalators. Neither of us knew where we were, and we walked aimlessly, looking for somewhere plausible to eat. I talked too much, blabbing on about long-distance relationships and problems with my Chicago boyfriend. Every so often Tamekia would glance sideways out of her sylphic stillness to laugh—at me, rather than with me, I assumed.

Finally we found a diner nondescript enough to serve as a backdrop to whatever scene was about to transpire. The waitress seated us in one of the green vinyl booths and handed us menus almost as long as our bodies, which Tamekia looked at askance, as if everything in this establishment—where, I noticed uneasily, most everyone was white—were suspect. But then she began to talk, freely, as a friend. She told me she was living with a couple of guys from Senegal, who’d introduced her to the “elders” in Chicago. The only thing she missed about Middle Tennessee, she said, was the food, though she was trying not to eat like that anymore. I was worried the white waitress would get shirty when Tamekia asked, Don’t you have anything vegetarian? But the waitress answered her matter-of-factly. The anxiety, apparently, was mine alone.

“I really didn’t know how to take your grandfather,” Tamekia said, with sudden frankness. Instantly the hazy light sucked in from the streets and haloed the booth; I felt Papa’s presence, as I often did, though it did little to console me. Since his death, I’d discovered depths of grief I hadn’t known my heart contained, a sobbing so powerful I was almost proud of it. My astonishment was still fresh at the fact that a man whose being had formed the very conditions of my existence could simply vanish.

“I’ve thought and thought about it,” Tamekia continued, “but I just can’t make sense of why this old white man would care so much about our people.” I saw, from the challenge in her eyes, that this was what she had been waiting to say, though the look wasn’t exactly confrontational; it was knowing, and it singed me, unexpectedly. It occurred to me that, in the year I hadn’t gone to Fairfield, Papa may have made her feel that she was important to him; maybe, in my absence, he’d even given her my place. His spirit welled up in me against my will, and I blurted, “I think he was just proud. Of y’all.”

We stared at each other across that wide chrome table, light glinting off the melon garnish, the water glasses. Something seemed to shift: the psychic plane on which we’d first met, or the ground beneath us trying to recalibrate. I didn’t know if what I’d said was absolutely wrong—I knew that there was no right thing to say—but when I looked up I saw that tears were running down Tamekia’s cheeks, and I felt them rolling down mine. I thought for a time that the mixed emotions of that moment captured the clash-and-chimes sound of the word “reconciliation,” the sound of violence passing through grief into fragile understanding. Though, now that so much time has passed, and I know Tamekia, and myself, a little better than I did then, it seems to me that the only honest thing that can be said of that spot in time is that it was one of those handful of moments in life that sears into us and never fades, precisely because it passeth understanding.

That was fifteen years ago, at least. My whole adult life has happened since then, as has Tamekia’s. Only recently— both, at forty, a bit mellower than we once were—have we been able to reconnect, bringing our various joys and tragedies with us, to contemplate the story of George Singleton again. Meanwhile, the story has continued to be told and retold, often on the back porch at Fairfield. Singleton-McMahon family reunions still take place at the house, usually the first weekend in August. The largest one hosted over one hundred descendants, from as far away as St. Louis, Chicago, and (in the case of Maurice, who had moved abroad in his retirement) Brazil. People camp out on the lawn, bringing their firepits and souped-up grills, and engage in feats of competitive barbecuing, teasing, and oral history recording. The elders take turns sleeping on Robert and Sally Sehorn Singleton’s Victorian beds, which are still propped in the high-ceilinged front bedrooms, though liable at any moment to fall through a rotten floorboard.

While I haven’t been able to make it to one of these gatherings in a decade, when I’m in Fairfield with my husband and daughters, several of George’s local descendants drop by to sit on the back porch and drink iced tea and tell stories. A few times, we’ve talked about writing a book—together. At one point, Mike Davis and I hatched a plan to start collaborating. At the end of our last phone call, he said, “We’ve got to tell this story to the world. Because it’s just like Twelve Years a Slave, but without any of the hatred or bitterness.” Mike and I have yet to collaborate, though, and I confess that I haven’t pursued this course as hard as I could have. I worry that a white person can’t utter such a tagline without coming off as an apologist for slavery. If I’m being truthful, though, I must admit to a different concern as well: In order to tell the story of George Singleton as it deserves to be told, with George and his descendants as the rightful protagonists, with their history as the history, I worry that I’ll lose the details that I inherited and observed in childhood, details of a Southern culture and mentality that may well have been fabricated in the service of propping up dead or malevolent ideals; details that, in principle, I am happy to torch alongside the Confederate flag, but which, in memory, remain indelible, and which are the only proof that this place, in which my father and my grandfather and his grandfather and I were all once children, is real. I worry that I will lose the proofs of my own existence. That is, of course, a melodramatic way of looking at it—a white way, one might say. For the reality is that, in America, it’s black folks whose histories have most often disappeared without a trace. In Fairfield, one need only roll back a desktop to see that.

Two summers ago Ella and Fred Davis, George Singleton’s great-granddaughter and her husband, came to Fairfield for a visit. In 1967, Fred opened one of the first independent African-American-owned insurance agencies in the South. Before that, black people could legally own homes but often couldn’t get them insured or were forced to pay exorbitant premiums, which effectively made home ownership impossible. The Davises brought friends of theirs, an internationally known African-American glass artisan and his wife, an education executive from Chicago. Walking through the house, the friends gasped—in awe, in horror—at all of the precariously preserved oldness. Most shocking to them was the long porch, bookended in screens and barely preserved from the elements, where my great-grandmother’s complete library rotted like wet leaves, ruined ideas of the late nineteenth century. The couple suggested getting PhD students from Tuskegee—they knew just the ones—in to catalog it all. My aunt and uncle politely said sure, and everyone drank their iced tea.

As everyone was doing one last tour through the house, the artisan noticed Sally Singleton’s old secretary and asked what was in it. It was the desk where Papa had kept the phone numbers for the lumberyard and the restaurant at Cortner Mill. But when we opened it, I remembered that it was full of pigeonholes, and each pigeonhole bore its own strange stash. One was stuffed with business cards, another with birthday notes. Then we found a roll of cash: Confederate greenbacks. In the last cubby hid a small, leather-bound notebook. Peeking inside the cover, we saw that it belonged to John Scott, Robert Singleton’s grandfather, one of Fairfield’s original settlers and the man, I startled to remember, Papa had referred to casually as “the slave trader at the end of the road.” Nobody wanted to touch it. We all just stared at it, diabolically valuable and unprotected. Afterward, my aunt shoved it in her suitcase and smuggled it back to Western Massachusetts in alarm at the idea of some trespassing rednecks getting their hands on it. Now, it’s sitting here on my desk, as vibrating and occult as Nat Turner’s Bible.

As an artifact, it’s extraordinary. It appears to have been entirely waterlogged at some point. The cover, once burgundy leather coated in green parchment, has eroded into a bumpy river-colored surface, veined and eaten white—here in lichen-like blebs, and there in fainter scourings, as on an ancient map. The spine is cracked in a ragged line from top to bottom, and the ropes of the binding show through. Its back is burnt nearly black in the middle, the bottom half torn up to bare, mottled board. If held up and toggled in the light, one word can be deciphered, maybe, on the front: Dad, written in script and followed by a symbol that looks like the head of Triton’s, or Satan’s, staff, or perhaps nothing at all but a trick of time. I wonder if I am committing an atrocity simply by describing it.

The first readable entry says, in ink, “Tuesday noon, 1809.” Everything else, written in pencil, has vanished. The next six pages detail dry goods, either bought or produced, mostly related to corn—corn fodder, corn meal, whiskey—in pencil and mostly unreadable. Then, in ink, a list arrives, without a heading:

| Toney | Born | 5 March | 1811 | |

| Charleton | ” | Dec 20 | 1807 | |

| Mingo | ” | July 16 | 1792 | |

| Justice | ” | Feby 14 | 1814 | |

| Luisa | ” | June 7 | 1819 | |

| Cupid | ” | Sept 15 | 1823 |

In total, there are twenty-eight names.

This is followed by another list, under the heading DEATHS. Here there are nineteen names, some of them with addenda. “Mary Anne had twins to die in labor.” “Jane had twins dead born 1838.” “June 25 Bob drowned by a cart running over him in St. creek.” The next page follows with a new heading: BIRTHS (NEGROES). Frankey. Miss Sally. Kull. Squire. Here are twenty-five names total, none of which appear to overlap with the previous list. More deaths are interrupted by a diary entry in which Scott details medical treatment he sought for a sick slave named William. “I brought him home Wednesday 19th for a few nights he complained very much of a blister, we drap’d it with . . . wax and oil one night when he complained very much of the plaster his mother put on cabbage leaves, it was after words drap’d with a greasy cloth.” The account ends abruptly, followed by another list of deaths. The last few record not actual deaths, but dates that Richard, Alick, and Betty ran away to the Yankees. The final two are babies, Forest and Nathan, born and laid to rest near the end of the war, almost certainly named after Nathan Bedford Forrest, who would go on to found the Ku Klux Klan.

A third of the way down the page, a newspaper article titled TO DYE COTTON YARN DEEP BLUE is stitched into the paper with white thread. The recipe instructs the reader to boil “logwood fine or chipped” in a solution of verdigris and alum to achieve a “elegant deep blue.” Halfway down is another list of births. Thirteen of them. On the facing page, Scott has included his own method “To Make Indigo,” more handwritten dyeing instructions (“Take any quantity of pokeberry juice, slice into crabapples . . . and simmer them until soft in an earthen or pewter vessel”) and drawings of a dye vat, a scythe, and a “coulter,” a knife-like contraption that goes before a plow to make a cleaner cut into the soil. Then finally, without transition, the last list of BIRTHS BROUGHT FORWARD: Fanny, Mahala, Mary, Forest, Tom, Eliza.

George Singleton’s mother was born Kitty Scott, and was likely “Kitty Anne,” listed in the notebook as having been born in February 1824. These human beings who lived at the end of the road, these names listed alongside ledgers for corn fodder, crimson dye, and scythes, were George’s people. This notebook, infinitely weighted by the souls it contains, is the image that lurches beneath the story of George Singleton, and which surely seeped into it, no matter how much he managed to elevate his own life. My hands shake, holding such an evil thing. Evil, but not extraordinary, really. Because, for every notebook like this, hidden in plain view, there are a thousand unread letters, twined up in cedar chests and shoved in drawers, shredded by mice to tatters, accordioning down into the fluff of used-up nests. Who knows what I might find if I read them all?

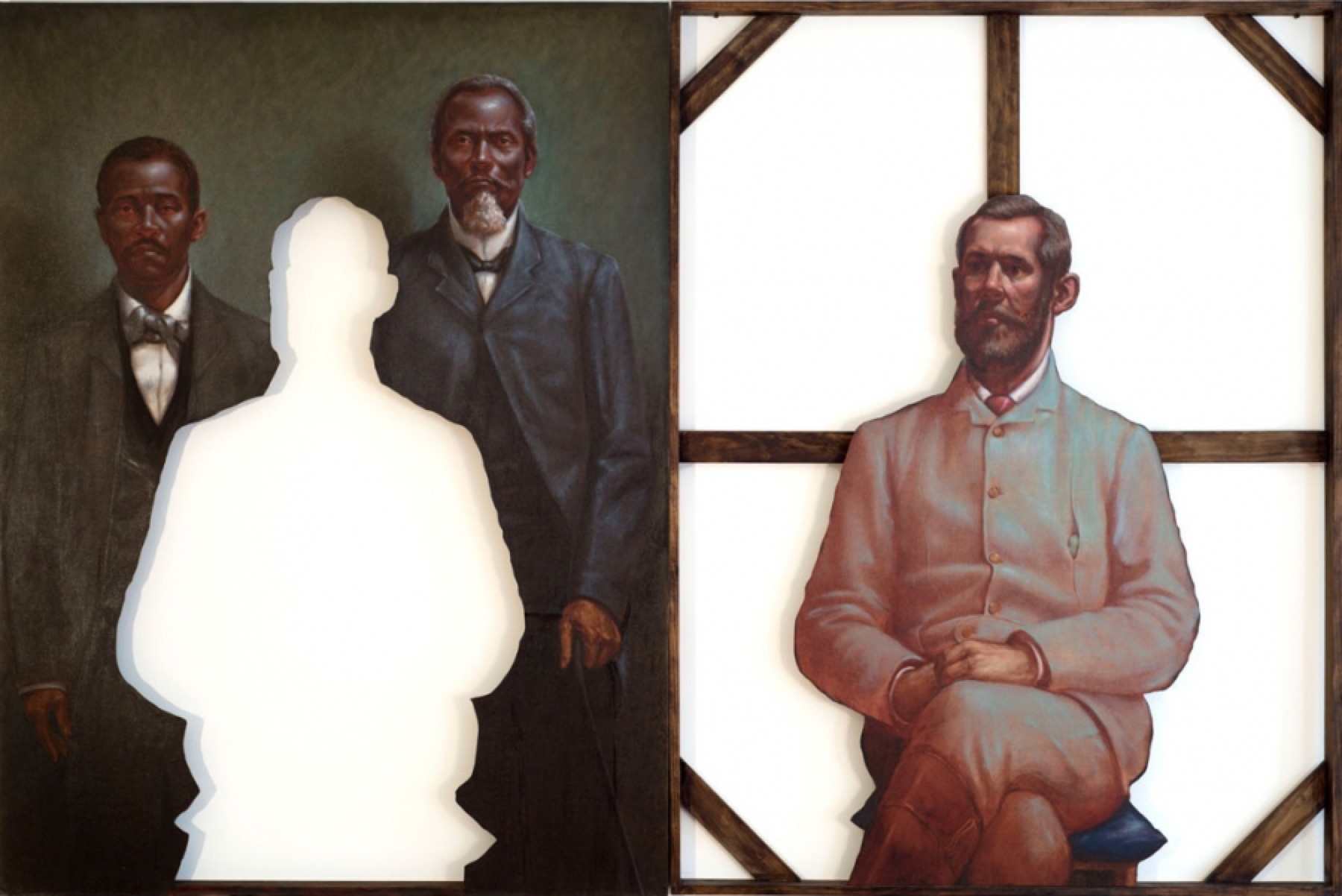

It’s practically rote, in academic conversation, to assume that stories like that of George Singleton are convenient constructions of the white supremacist version of history. The story, after all, can be told in a different way entirely. A former slave in the mold of Uncle Tom (Papa called George “Uncle George” to his dying day) saved his master out of brainwashed devotion. Even after having gone off to fight for the Union— perhaps simply the most practical choice— he was psychologically incapable of freeing himself from the pattern of trauma, abuse, and debasement he knew from slavery. The vicious racism of Reconstruction had made it impossible for his sisters to escape, so he returned to the site of his former enslavement and stayed. Entrapped in his old role, he labored on behalf of his white slave mistress and her daughters—all ready to starve before stooping to the plow themselves—and eventually once again submitted himself to his former boyhood “friend,” who, in all practical ways, remained his master. Despite this black man’s loyalty to the white family, his former master nevertheless found a way to extort the price of George’s farm from him (which a deed shows George paid an exorbitant three thousand dollars for), while keeping him close enough to have a servant-for-life.

American history by no means makes the above narrative impossible, or even unlikely. Yet, in this case, I’ve learned that it’s as insulting to “the black side of the family” as it is to the “white side,” for it discounts George’s acts of courage and kindness as much as, if not more than, Robert’s. When I’ve posed even a hint of this version of events to George’s descendants, they’ve bristled. “George Singleton had a lot of respect in these parts,” Elwood said recently, widening his eyes and settling them on me, as if daring me to continue. “From black folks and white folks both. You know, when he and Barbara sold that house, the whole county came to the tag sale, and white people bought their furniture!” Hearing the conviction in his voice, and knowing how much he’d stake on it, I admit that I have trouble finding the courage, or the evidence, or any good reason, to contradict him.

This year, for the first time in several years, we organized a potluck dinner at Fairfield. Thirty or so of Ella and Elwood’s kin, all descendants of Jack and Kitty Singleton, George’s parents, showed up. They came from as far as Memphis and Jackson, but as close as Bugscuffle—so named, Elwood says, because a man passing through once made note of the single event that took place while he was in town: two bugs having a scuffle on a cow pie. They came in the middle of a downpour that sequestered us all inside the dining room of the old tavern, creating an atmospheric event, a sprawling African-American family feasting on chicken and deviled eggs and blackberry cobbler and caramel cake (“camel cake,” my daughters now call it) among the very furnishings that their ancestors may have carried in on their backs a hundred and fifty years before. Men named Junebug and Joe Lee ate spicy baked beans while studying the architecture. Teenagers—Jasmine and J.J.—FaceTimed friends, sitting side by side on the inside porch swing. The backdrop was the wall of rotten books that contained—and still contain, though warped by mildew and dotted by bug excrement now—the racist ideas that had justified the enslavement of their foremothers and fathers, as well as the egalitarian ideals of a better America, side by side. If you listened, you could hear the river. With all the rain, it was rising rapidly between the rocks, the water from Jack’s Hole crashing over the dam into boils.

Before we ate, Elsie, a missionary in the Church of God in Christ, asked Fred Davis to bless the food. Fred is a dignified presence with a flair for high oratory, winningly cut by his scandalous laugh, as well as his tendency to pull his cap down over his eyes and fall asleep under it after dinner. In addition to his career providing insurance for African-American homeowners in the South, Fred had been on the Memphis City Council during the Sanitation Workers Strike, which was the event that had drawn Martin Luther King Jr. to Memphis, where he was killed in April of 1968. Next to Fred, one feels how close the civil rights era is, despite the Trumpian claim that it’s ancient—and settled—history. When Fred prayed over our food, he boomed with a force that remembered every firebombing. “Lord!” Fred prayed. “Thank You for this unique family. Thank You for allowing us to know and respect and even love each other across generations, and across races. Thank You for keeping our connection alive. Lord, we pray that you will let us know how we can be an example to others in this country, to show how You said All Your People should live.”

After dinner, Elwood held court on the back porch. Eventually he got around to, as he often does, the story about the lady at the nursing home who told Cheryl, Elwood’s sister, “I know who y’all are. You’re those uppity Singletons.” This anecdote always makes Elwood chuckle with pleasure and return to the story of George Singleton. “The way I reckon,” he said, “it must have been a good relationship between George and Little Robert because, when the war was over, Grandpa must’ve considered, Hmmm I fought for the North and Little Robert fought for the South, don’t know how that’s gonna go, and here I am, free, with a pocketful of money. He didn’t have to come back. He had two sisters in Fairfield, but he didn’t have to stay—he could’ve come down, snatched them up, and run off again, but he didn’t. He stayed and he took care of both families. Black and white. Grandpa took care of them for two years before Little Robert came home. The way I see it, he gave him that piece of land up there to pay him because he done that. I’ve seen the piece of paper that they wrote up, and it says George paid him three thousand dollars for that piece of land!” Elwood pulled a face, retracting his chin way back into his neck. “Now where’s a black man going to get three thousand dollars back then?”

“So you think Robert just made it look like George paid him so that the other white folks wouldn’t object?” I asked.

“That’s right,” Elwood said, pointer finger astride his jowl to add to his affirmation. “So that couldn’t nobody take it away from him.”

I’d brought John Scott’s diary in case anyone wanted to look at it, but it seemed there was no time, no opportunity to fit it into conversation. At some point Ella and Leonard got to giggling, hands on each other’s knees, over how Aunt Odie Kay used to pour straight Carnation evaporated milk on cereal: Didn’t nobody tell her you’re supposed to dilute it? Man, she’d fry chicken and apples every day—for breakfast. Then Sandra got brought into it. Junebug’s Mama, she was crazy for corn. You don’t eat much corn now, do you, Bug? That’s how I am about beans—I didn’t know anything about Great Northern; those were just white beans to me! By then Pam and Elsie and Jasmine and J.J. had to take off. Pam and Elsie hugged us close, sweet-tea mugs in one hand; they held our daughters’ faces and told them they loved them. We told them we loved them back. I suppose I might have interrupted all of this unlikely loving-kindness to remind everyone of the evil that had been perpetrated upon their ancestors by mine. As if they didn’t already know. As if they hadn’t already chosen to forgive, in order to let the other story, the story of George Singleton, survive.

After everyone had left, another hard afternoon rain came through, followed by a lemony, early-evening sun. I walked down to the river in that calm, wondering how I could possibly contain it all—the greens and browns and creams unloosed, the light, mild and various as melons. How would I ever explain why we baked Elwood McMahon three blackberry cobblers, from fruit picked that morning; how the brakes ached with all that glowering a good soak in sugar-water would have sweetened, as Fred Davis pointed out? My footprints sank in the wet violets humped between the wheel ruts everyone had driven over to get here. I heard the river gushing through the tangle where mosquitos whine, and I remembered that, as a girl, I wasn’t allowed to go down to the water alone.

The storm now made the danger of it plain. Mud gushed between banks in sloshing torrents, and the heron that usually stands on the gravel bar glided above, searching for higher ground. I stood there, surveying the tumult. The risk of this place—of loving it, of owning it—had never been clearer. Then, out of the river’s rush, I heard a chirp: raspy, loud, an unfamiliar bird gnawing into the air, half-warble and half-bark. I couldn’t imagine what it was. The sound was entirely new to me, and it repeated, insistently. I looked down, and onto the bleached-out fork of a caught tree trunk that had stuck out of the rocks for twenty years, a creature nosed up: a snapping turtle or snake I assumed. But, no; now the whole oil-can head appeared; then hand-like paws, grasping; then the body, a foot of pelt and sinew intermingled. An otter.

I stared—I’d never seen an otter in Fairfield, nor heard that anybody had. He stiffened his neck and barked, a hoarse and woeful plea. He was so close to me I could see the valves of his nostrils dilate. Then he barked again, and they emerged on the opposite bank: five more otters. They wriggled out into the water, swiftly muscling against the boils to reach his call, bounding to our side of the river, and, when they were close, he aimed himself into the current and leapt, so that, one by one, they crashed into him, and clutched. In that instant, they made of themselves a raft, and without hesitation the first otter began guiding them downstream, dodging the branches that had been dashed down by the storm. He led them as far as I could see, and they held on to him and to each other, slick backs writhing, riding the flood, together.

I don’t suppose I would have believed it either if I hadn’t seen it myself. But I am here to tell you that it happened. That, and much else besides. Right here. In Fairfield, Tennessee.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.