Atlanta Hellride

By Noah Gallagher Shannon

There was no telling how long the stoplight at the base of the 8th Street hill would stay green when Grant Taylor began bombing toward it. He was in a low crouch, muscling his skateboard against the blacktop, popping ollies and carving tight S curves down the center stripe of one of midtown Atlanta’s steepest streets. With each push of his left leg, exponentially more asphalt roared past him. He wore a gray t-shirt, green chinos shredded in the ass from weeks of slamming, and a pair of Nike Blazer Lows—Taylor’s signature professional skateboarding model. His corduroy trucker hat had long since sailed off. A half-mile ahead, at the intersection with Peachtree Street, four lanes of traffic stood idling, waiting for the light to turn. He pushed faster.

It was a muggy afternoon in late March, and over the last few hours, Taylor had been driving us around his hometown, stopping at various spots while the sound system cycled through Bad Brains, OutKast, and Gregory Isaacs, and the entourage combed through fresh footage, rolled joints atop overturned boards, and shared stories about gruesome falls and bad tattoos. It was a typical Saturday; among the guys present were a handful Taylor has known for going on twenty years: Patlanta, Bucky, Sethtafari. But the day also served as a guided tour of the Atlanta skate scene for Six Stair Studios, a California-based production company, in town to shoot an episode of its popular web series “Love Letters to Skateboarding.” Not to be outdone, these dudes introduced themselves as Buddy, Pizza Box, and Baby Girl.

The host of the show, Jeff Grosso, stood next to me, watching Taylor hike back up the hill. A legendary skater in his own right, and survivor of three heroin DOAs, Grosso’s second act, at age fifty, is a fitting one for his misfit eminence; on “Love Letters,” he interviews skaters, airs old grievances, and narrates an insider’s history of skateboarding through its various guises: art, travel, punk, drugs. Vice has called him the last bastion of free speech in an increasingly corporatized skateboarding. For a culture still figuring out how it went from adolescent criminality to the 2020 Olympic Games in two generations, Grosso might just be the most trusted old head among the whiplashed.

“Grant is like a fucking social experiment,” Grosso said. He was recovering from major spinal surgery and wearing a bone stimulator around his neck, which looked like a plastic ox yoke and forced him to turn his whole body awkwardly as he gestured around at the lunacy of the scene before us: the hill, the school bus, the metal music blaring at top volume on a city street. By way of explaining Taylor’s behavior, Grosso took on his voice: “‘You want to hear these tunes; you want to be part of this.’” He shook his head, laughing, and dragged on a cigarette (which he is definitely not supposed to be doing, post-surgery, he told me, grinning). It wasn’t just about freaking people out, he clarified, it was about keeping the revved-up spirit of skateboarding alive the whole day. “If you’re doing it correctly, you’re not mired down by people, by the business of it,” Grosso told me later. “Every time Grant steps on the skateboard he rolls fucking full throttle, and he does it effortlessly.”

That’s about as shining an endorsement as one’s apt to receive in skateboarding. It’s in the cultural DNA to spurn authority and look sideways at any kind of formal accolade. (The symbolic self-harm caused by skateboarding’s recent inclusion in the Olympics is hard to overstate.) Suffice to say, the respect of an OG like Grosso carries as much weight as anything on the steadily accumulating list of Taylor’s accomplishments. There is only one prize that matters in skateboarding, and that is Thrasher magazine’s Skater of the Year, which Taylor won in 2011, when he was twenty. For Jake Phelps, the editor of the San Francisco–based magazine—who has been likened to a degenerate Anna Wintour, dictating the tastes of a vast teenage underworld—Grant Taylor is already up there among the immortals. He skates unreasonably fast and aggressively, a beautiful embodiment of skating’s ugly menace. But perhaps just as important to Taylor’s legacy is his attitude toward it. Later on, when I asked to see his SOTY trophy, he told me he didn’t know where it was. “I’m just not that type of dude,” he said.

The episode Grosso and the Six Stair guys were filming would be dedicated entirely to the city of Atlanta, with Taylor as its central fixture. However global skateboarding has become—and today, you can find girls-skate nonprofits in rural Afghanistan and mini-ramps built deep in the Namib Desert—it is still to a large extent a California-based phenomenon. Its historical roots lie in Southern California surf culture, and nearly every board, shoe, and apparel company is headquartered there. Even as skateboarding has migrated from full-length films to online clips, most professional skaters choose to live somewhere between San Diego and San Francisco. But Taylor never made that pilgrimage. He still resides in the northeast Atlanta neighborhood of Little Five Points where he grew up (making him only the second person to win SOTY while living outside California). The “Love Letters” episode, it seemed, would try to understand Taylor’s Atlanta as the central question about, and answer to, his enduring radness.

When Taylor finally climbed back up to us, he bumped a few fists but said next to nothing, almost immediately dropping into the hill again. Carving wide this time, he popped onto the sidewalk and ollied over a standpipe. Seconds later, as the sidewalk leveled out for a driveway, he used the bump to glide an ollie up and over a bike rack ten feet away. Then he was back in the street again, bombing through a yellow light.

There’s a video you can find on Vimeo of Taylor skating when he was a kid in the late nineties—a compilation of tricks from when he was five and six, many of them filmed on the cul-de-sac in front of his childhood home on Seminole Ave. The video is not one of Taylor’s more popular ones, produced by his sponsors, which now garner millions of hits online; it’s a segment from a 1998 video called Black Box made by a now-defunct Atlanta company called Torque Skateboards. Torque was started by Grant’s father, Thomas Taylor, a former professional skateboarder who grew up in the nearby neighborhood of Morningside and opened a local skate shop called Stratosphere in 1986. In the late eighties, he moved the shop to the Little Five Points neighborhood, where he met Grant’s mother, Rachel, while out skateboarding with her brother, and Grant grew up there, on Seminole Ave., in the same house—a large yellow Victorian—where Thomas still lives. Although Grant’s parents divorced when he was a teenager, his life has remained an uncanny reflection of this early video. In certain frames, you can hear Thomas cheering on his son’s skateboarding and catch glimpses of the house, two doors down, that Grant would later buy with his professional earnings. The video’s soundtrack is Iron Maiden’s “Phantom of the Opera.”

Grant refers to Thomas, who is fifty-one and still skates regularly, as his “old man,” but their relationship is in certain ways more brotherly than father-son. Grant reveres his father, and consults with him on his sponsorship contracts, but they also go skate and drink together. Each is a member of the other guy’s crew. “A lot of kids look up to their fathers as their idols when they’re young,” Grant told me. “It just so happens that I looked up to my dad for skateboarding and I started skateboarding.”

In 2015, Thomas directed a documentary called Lost in Transition, narrating the Southern skate tradition he himself had grown up in. It’s sketchy on chronology and wider context, but filled with rare and weird footage collected across Georgia, South Carolina, and Florida. Between 1983 and 1990, when skateboarding’s first wave of seventies cool finally crashed, most of the South’s for-profit skate parks were forced to close, leaving a void in public places to skate. This set the stage, as the documentary argues, for a backyard revolution. After figuring out they could build a thirty-two-foot-wide vert ramp for as little as twelve dollars (or a trespass onto a job site), Thomas and other local pros like Tim Payne, Jimmy O’Brien, and Lenny Byrd set about throwing them up wherever they could. They poured concrete objects and drained swimming pools, too, naming the previously abandoned spaces things like Blue Room, Mickey Mouse Head, and Po Folks Pool. Some of their DIY designs would eventually become industry standard. The first flat-bottom vert ramp was probably built in Georgia, Thomas said, while Skatezone in Lithonia, outside of Atlanta, almost certainly featured the world’s first indoor wood vert bowl. They had stickers made up that read, WE DON'T GIVE A FUCK HOW THEY DO IT IN CALIFORNIA. “Why have you not heard the Southern story yet?” Thomas asks near the beginning of the documentary. “Because we didn’t give a fuck.”This is the lineage into which Grant Taylor was born. He came up skating concrete parks, pools, and backyard ramps—what’s called transition skating—in the aughts, a time when skateboarding was, for the most part, progressing away from these forms and toward more technical street skating on stairs, ledges, and handrails. Taylor skates all that, too, but does so with a raw speed and connection to his board honed on steep and unforgiving surfaces. This all-terrain assault has endeared him to the old school—who see something of skateboarding’s crude origins in his style—and startled his contemporaries. A fellow Atlanta pro named Justin Brock remembered traveling to L.A. around 2008, only to find all anyone could talk about was Atlanta, Grant. Two of the tricks Taylor had become best known for then were backside and frontside airs, in which he scooped the board out of the lip of transition rather than ollieing. They were old tricks, perhaps the oldest, but for twenty years few were doing them. After Taylor won SOTY, though, Michael Burnett, a photographer and editor for Thrasher, told me he started noticing young street skaters adding them to their bags of tricks.

Taylor credits his style, at least in part, to force of circumstance. “It’s just adapting,” he said, likening the way the local skate scene developed to that of Atlanta hip-hop; free of coastal influence, they did what they wanted, with whatever they had at hand. (For all its outward subversiveness, skateboarding still struggles with inclusion; the Atlanta scene, probably owing to the city’s demographics, has traditionally been more diverse.) And for much of Taylor’s childhood, this meant metal and wood ramps built behind his house. In 1996, during the run-up to the Atlanta Games, the Olympic Committee staged the training for the closing ceremony’s skate performance on Thomas Taylor’s homemade vert ramp. After that, a six-foot mini ramp was put in. Finally, in 2002, Thomas began digging out the yard with a Bobcat, planning to pour a two-tiered concrete bowl. Today, the bowl has grown to encompass most of the yard, including the garage, which is engulfed on two sides by swales, hips, and banks of concrete. Since Grant bought the place next door, in 2013, father and son have shared a fence-line and backyard bowl. It is a gnarly, beautiful bowl—the staging ground for Atlanta skateboarding—and no one skates it better than Grant.

It is impossible to exaggerate just how hard Taylor rips this thing. (On YouTube, just type in “Grant’s Bowl.”) The deepest corner of the bowl is 8.1 feet high, the concrete is uneven and wonky in places, and many professional skateboarders struggle merely to grind the pool coping surrounding its edges. But Taylor airs out of it, sometimes floating so high that his body brushes up through the tree branches hanging ten feet above the lip. The power and speed he coils, pumping against the waves of concrete, doesn’t spring suddenly out of the lip, as it does for most skaters, but somehow unspools, gently. There’s long been a catalogue of local lore—which has become wider skateboarding lore—of the impossible-sounding shit Taylor’s done here. In Nike’s Debacle video, filmed in 2007, he whips around the bowl once, then uses a sketchy concrete bank to carry all four wheels up and across the sidewall of the garage for fifteen feet, scrunching his body under the tin awning, until his back truck grinds the bottom lip of the garage’s side window. Multiple local dudes I talked to said no one had much noticed the window was there before Taylor grinded it. He’d re-imagined a new surface.

This creativity was on display throughout our bus tour of Atlanta, but especially when we skated a legendary spot called Bell South, a wide urban plaza with banked architecture. Taylor flowed through several lines here, one after another without rest, linking together tricks on ledges, down stairs, and on the plaza’s distinctive sloped granite walls. At one point, he disappeared behind a corner, only to be discovered trying to grind a fifteen-stair handrail, sending the cameramen scrambling for their gear. “For years, Grant would purposely try to land tricks first try just so the cameras wouldn’t be ready yet,” Brock told me, laughing. “Most of the gnarliest stuff—the best stuff—he’s done, it isn’t on camera.” This attitude flies in the face of skating’s media-driven economy, particularly now that many skaters have Instagram accounts with millions of followers. Although Taylor participates as much as anyone (he has to contractually), his ambivalence and irascibility toward photography and filming—or at least toward the way equipment and staging interrupt his rhythm—harkens back to an older, hardcore spirit of skating. As Thomas says in Lost in Transition, “Back then everyone just said, ‘Put the fucking camera away, you know, let’s skate.’”

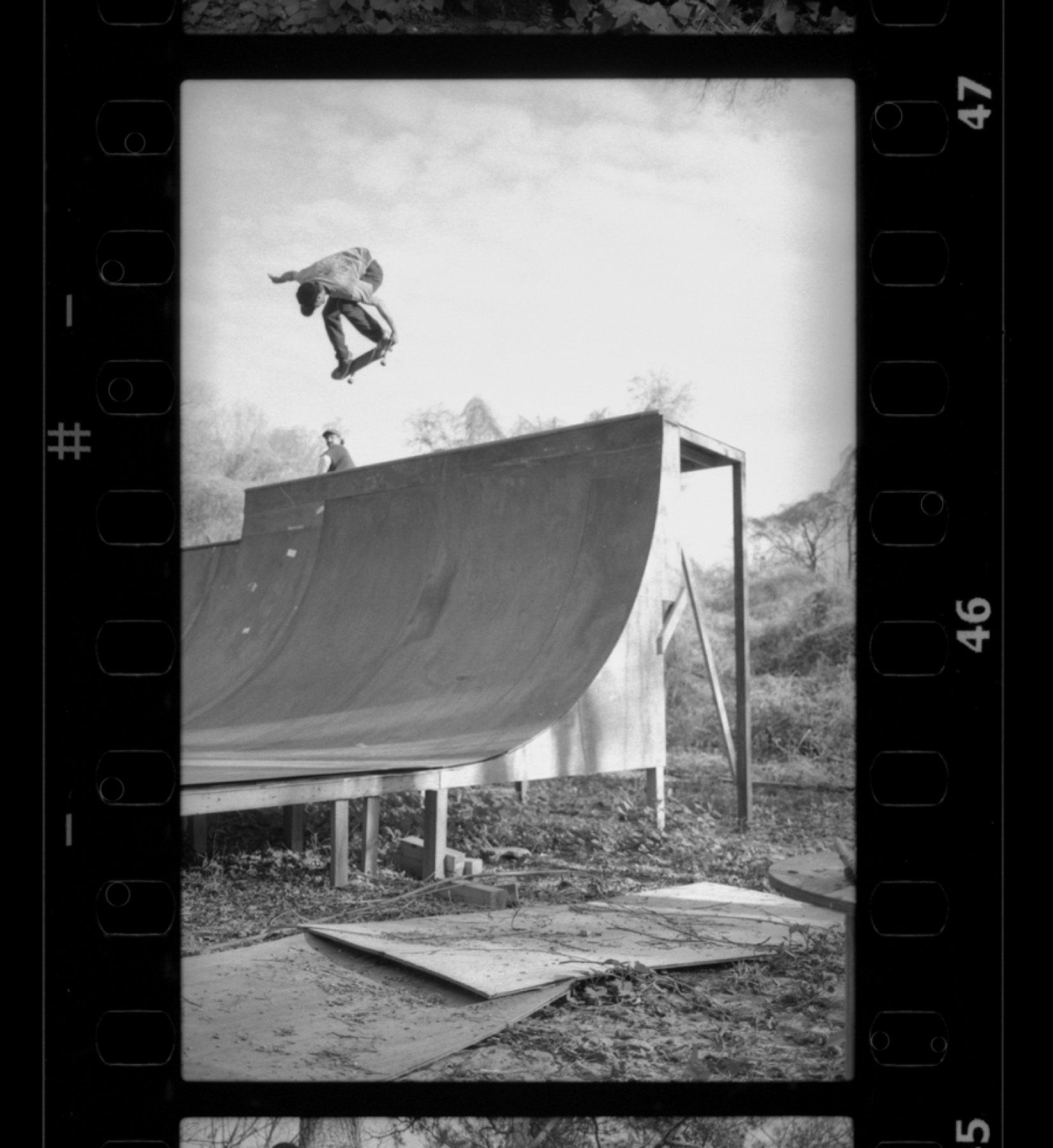

Back in the bus, we made our way east of town, to a house set back off the road in a copse of Georgia pines. Pickups and motorcycles were parked at any angle on the lawn. Several windows were boarded up and the rail was missing from the second-floor porch. Inside, a blues band worked through some numbers led by a guy named Load, an old ramp shark with a long gray beard, who blew on a harmonica over slide guitar and drums. In the kitchen, a chopper sat partially deconstructed amid an army of beer cans. The house was owned by Slim—the eighties pro Jimmy O’Brien—who also owns Slim’s Garage, a custom motorcycle shop in west Atlanta. If it was unclear as to whether Slim or anyone else lived in the house, its purpose was immediately grasped: out back sat a ramp, some thirty feet wide and six feet tall. Up on the deck, ten or twelve guys, including Thomas and a few of the old pros, took turns with Grant, heckling him as he set about blasting frontside airs. There was a cooler deep with beer, and someone manned the grill. The scene appeared lifted straight from the frames of Lost in Transition. Even the ramp, as I learned, contained bits of salvaged wood and coping from previous backyard ramps, dating back twenty years.

As the light dwindled, a guy with butt-length dreadlocks named Peyton climbed a ladder and bolted a spotlight onto a pine, and people skated deep into the night. (Peyton, along with many of the guys there, is a gaffer and rigger for Atlanta’s exploding movie and television industry; “I did those fucking talking lights on Stranger Things,” one guy told me.) After taking several videos of Taylor and sending them to astonished buddies back home, I wandered over to the Six Stair crew. Earlier in the day, Bradley, one of their young filmers, had bailed on a trick and landed awkwardly, snapping his tibia bone audibly. (A skate crew, deep enough and stocked with enough old timers, is a crowd-sourced medical degree; as soon as we heard the sound, a couple of guys ziplocked ice while other guys stacked boards to elevate his leg and discussed diagnoses.) Now he reclined calmly, sipping at his beer. When I asked what to make of the backyard session—if anything similar ever occurred in California—Rick Charnoski, one of the co-owners of Six Stair, chimed in with a no.

“As free and open as skating is, there’s still a lot of bullshit,” he said. “Down here, with the Taylors, it’s just skating at its best. It’s like a renaissance kind of thing in the South.” He said that Atlanta was the best-case example of how to grow a hometown skate scene, and he pointed at Grant. “This is skateboarding anywhere; how we tell our story. They’re just telling the best and truest one.”

For someone who’s defined his career through a near-constant barrage of speed, Taylor is remarkably comfortable at rest. I spent much more time with him off the board than on, in fact, hanging out at the home he and his wife, Lily, share together on Seminole Avenue. Airy, rustic, and tidily decorated with photographs from the couple’s wedding last September, the house is conspicuously free of skate paraphernalia. Because Taylor travels so much of the year (in just the first three months of 2018, he went to Ecuador, Tampa, San Francisco, Brazil, and Peru), the couple takes care to carve out time away from skateboarding. They like to try out new recipes, walk their cattledog, Ozzy, and wander Oakland Cemetery when the famous landscaping comes in bloom. On the first morning I visited them, Lily, who works as an Intensive Care Unit nurse at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, was already in for her shift, but Grant was cooking breakfast—a farmer’s market scramble—and offered me a plate.

Although you could catch glimpses of the bowl next door, where already at this time tomorrow guys would be gathering to build a bonfire and skate for several hours, Taylor’s home stood in stark contrast to his father’s. The irony was not lost on him: it was the son’s house, the professional skateboarder’s house, that was the quiet sanctuary, while the father’s remained the party lair with a record room. Taylor built the fence, he said, for this exact reason; he didn’t want bowl sessions inevitably spilling over. While his childhood home had always been a skate house—with boards nailed up on the walls and touring pros sleeping over—in the years since his folks divorced and two sisters moved out, it has gradually become a bachelor pad. “He’s never going to change,” Taylor said. That’s just who he is. So maybe I’ve seen that and chosen parts of that life I want to live, and other parts I see I want to change and be my own person.”

What he has seen, at least in part, is a lifestyle perhaps unavoidably saddled with loss. Just a few weeks before Grant and Lily were married, a fellow Nike rider named Cory Kennedy crashed his Audi while driving home from a skate session outside Seattle, killing one of his passengers, Thrasher videographer Preston Maigetter. P-Stone, as Maigetter is known, had been a beloved, avuncular figure to many of skateboarding’s wayward young pros, particularly for Taylor, who was crushed. He got a tattoo commemorating P-Stone, inscribing pma—Preston Maigetter Attitude—inside his right bicep. When Taylor spoke of his own grief, relaying how hard the last months had been, it was tinged in anger and disbelief—of the loss, but also, it appeared, his own acceptance of it. Perhaps more so than his peers, Taylor’s ability to go on the road and raise hell, to channel a punk ideal of skate culture through his riding, had made his career. But he’s worked to—“not turn it off exactly,” he said, “but play both parts,” a skater and a mortal. This wasn’t to say one or the other side was a façade, he clarified, but that both required similar dedication and focus, if they were to feed each other, as they must for so many artists and athletes. In recent months, he and Lily had discussed moving to L.A., he said, focusing on what it would entail for their shared life and his own inside skateboarding.

This resonated with me, both as a writer and as someone who grew up skateboarding. Skateboarding appeals to your teenage years and impulses, because it offers an outlet for certain raw but eternal preoccupations: rebellion, masochism, the blooming of individual style. But skateboarding’s worldview can often become so totalizing that commitment to it far into adulthood, past the age when it’s socially acceptable to ride around in a school bus smoking weed and listening to Slayer, can look like protracted adolescence. This is why skateboarding, for a large chunk of the country, will never fully outgrow its degenerate associations. And that’s fine. Skateboarding is a deeply personal act—subject to whims of attitude, style, and terrain, as well as the viewer’s taste for them. It’s why a certain breed of skater will forever claim that skateboarding is not a sport at all, as it lends itself more readily to the subjective appraisals we afford art, acting, literature. I do not completely agree, but I would submit that Grant Taylor is not escaping backward when he skateboards. He is channeling something inner forward, urging it with speed and power and a closeness to pain, to render it briefly beautiful. Not many of us would attempt that, but how many can identify?

If that sounds a little corny—and it might to Taylor—it’s only because skateboarding so often traffics in the language of self-discovery. In The Body Corporate, Six Stair Studios’ latest video with the Anti Hero team, Taylor and others share sentiments about what first attracted them to skateboarding, many of them touching on loss, family members, and chaos in their private lives. “I was already the outsider and then I picked up a skateboard,” one says, “but then you see other skateboarders, and they’re dealing with that same thing, too, but they don’t care; they’re breaking out of it to just be able to do what they want to do and express themselves in a different way.”

While we ate, Taylor queued up footage from the first annual P-Stone Invitational, an invite-only contest put on in March by Thrasher and Anti Hero in Maigetter’s honor, held at the infamous, unpermitted skate park “Lower Bob’s” in Oakland. For thirty-two minutes, the irredeemable soul of skateboarding was on full display: fires, live metal music, drunk people falling off ramps, a “jam” format that almost by design invited high-speed collisions. Taylor didn’t comment on much of this. He’d put together some incredible skating and come in second, but appeared not to register himself at all on the screen. Near the end of the video, when a skater named Raney Beres, who ended up winning the competition, hung a huge backside air, Taylor reacted with a deep guttural noise. It wasn’t a particularly special trick, but one he must have recognized something in. It reminded me of what Taylor had told me he loved most about skateboarding. “When you see someone like that just ripping their local park, who has it completely dialed and doesn’t care who’s watching or who’s paying attention,” he said. “That’s the sickest part.”

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.